International companies must decide how much to adapt their marketing strategy to local conditions.52 At one extreme is a standardized marketing program worldwide, which promises the lowest costs; Table 8.1 summarizes some pros and cons. At the other extreme is an adapted marketing program in which the company, consistent with the marketing concept, believes consumer needs vary and tailors marketing to each target group. A good example of the latter strategy is Oreo cookies.53

OREO In launching its Oreo brand of cookies worldwide, Kraft chose to adopt a consistent global positioning, “Milk’s Favorite Cookie.” Although not necessarily highly relevant in all countries, it did reinforce generally desirable associations like nurturing, caring, and health. To help ensure global understanding, Kraft created a brand book with a CD in an Oreo-shaped box that summarized brand management fundamentals—what needed to be common across countries, what could be changed, and what could not. At first, Kraft tried to sell the U.S. Oreo everywhere. When research showed cultural differences in taste preferences—Chinese found the cookies too sweet whereas Indians found them too bitter—new formulas were introduced across markets. In China, the cookie was made less sweet and with different fillings, such as green tea ice cream, grape-peach, mango-orange, and raspberry-strawberry. Indonesia has a chocolate-and-peanut variety; Argentina has banana and dulce de leche varieties. In an example of reverse innovation, Kraft successfully introduced some of these new flavors into other countries. The company also tailors its marketing efforts to better connect with local consumers. One Chinese commercial has a child showing China’s first NBA star Yao Ming how to dunk an Oreo cookie.

1. GLOBAL SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES

The vast penetration of the Internet, the spread of cable and satellite TV, and the global linking of telecommunications networks have led to a convergence of lifestyles. Increasingly shared needs and wants have created global markets for more standardized products, particularly among the young middle class. Once the butt of jokes like “Why do you need a rear-window defroster on a Skoda? To keep your hands warm when pushing it,” the Czech carmaker Skoda was acquired by VW, which invested to upgrade quality and image and offer an affordable option to lower-income consumers worldwide.54

At the same time, consumers can still vary in significant ways.55

- The median age is only about 26 or 27 in India and Mexico and 35 in China but about 43 to 45 in Japan, Germany, and Italy.56

- Doughnuts don’t appeal to British consumers for breakfast, while Kenyans need to be convinced that cereal is a good option.57

- When asked whether they are more concerned with getting a specific brand rather than the best price, roughly two-thirds of U.S. consumers agreed, compared with about 80 percent in Russia and India.58

- The percentage of the population online varies wildly across countries: United Kingdom (85 percent), Japan (80 percent), United States (79 percent), Brazil (40 percent), China (34 percent), and India (7.5 percent). U.S. Internet users spend an average of 32 hours per month, compared with 16 hours globally.59

Consumer behavior may reflect cultural differences that can be pronounced across countries.60 Hofstede identifies four cultural dimensions that differentiate countries:61

- Individualism versus collectivism—In collectivist societies, the self-worth of an individual is rooted more in the social system than in individual achievement (high collectivism: Japan; low: United States).

- High versus low power distance—High power distance cultures tend to be less egalitarian (high: Russia; low: Nordic countries).

- Masculine versus feminine—This dimension measures how much the culture reflects assertive characteristics more often attributed to males versus nurturing characteristics more often attributed to females (highly masculine: Japan; low: Nordic countries).

- Weak versus strong uncertainty avoidance—Uncertainty avoidance indicates how risk-aversive people are (high avoidance: Greece; low: Jamaica).

Consumer behavior differences as well as historical market factors have led marketers to position brands differently in different markets.

- Heineken beer is a high-end super-premium offering in the United States but more middle-of-the-road in its Dutch home market.

- Honda automobiles denote speed, youth, and energy in Japan and quality and reliability in the United States.

- The Toyota Camry is the quintessential middle-class car in the United States but is at the high end in China, though in the two markets the cars differ only in cosmetic ways.

2. MARKETING ADAPTATION

Because of all these differences, most products require at least some adaptation.62 Even Coca-Cola is sweeter or less carbonated in certain countries. Rather than assuming it can introduce its domestic product “as is” in another country, a company should review the following elements and determine which add more revenue than cost if adapted:

The best global brands are consistent in theme but reflect significant differences in consumer behavior, brand development, competitive forces, and the legal or political environment.63 Oft-heard—and sometime modified— advice to marketers of global brands is to “Think Global, Act Local.” In that spirit, HSBC was explicitly positioned for years as “The World’s Local Bank.”

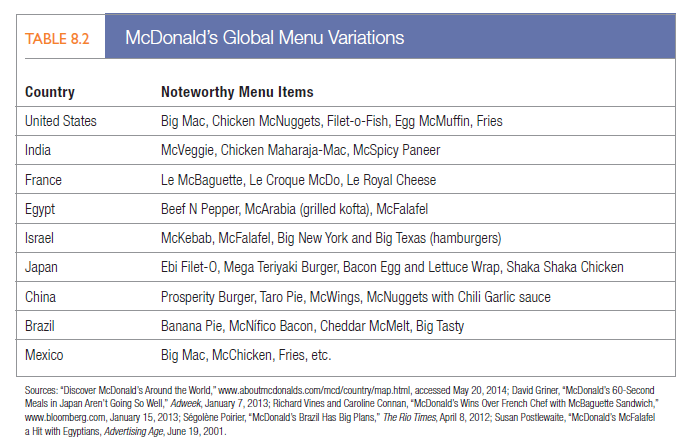

Take McDonald’s, for example.64 It allows countries and regions to customize its basic layout and menu staples (see Table 8.2). In cities plagued by traffic tie-ups like Manila, Taipei, Jakarta, and Cairo, McDonald’s delivers via fleets of motor scooters.

Companies must make sure their brands are relevant to consumers in every market they enter. After highlighting how Amazon and Netflix are entering global markets, we next consider some specific issues in developing global product, communications, pricing, and distribution strategies.65

AMAZON AND NETFLIX Two of the most successful marketing companies in recent years, Amazon and Netflix are going overseas to fuel their rapid growth, but they are also finding themselves butting heads as they both seek to become the market leader for digital movie downloads. The older of the two, Amazon has been overseas longer, finding much success in the United Kingdom, Germany, and other parts of Europe. Amazon has also moved into Asia-Pacific but has found progress in emerging markets like China to be slow. Amazon acquired LoveFilm, a European DVD rental and movie-streaming business, to compete with Netflix. It also opened up a massive media R&D center in London and expanded its Android-based Appstore distribution business to cover 200 countries. Netflix has expanded aggressively overseas, starting with Canada in 2010 and Latin America in 2011 and then the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Nordic countries in 2012. Although its international base of more than 6 million consumers is formidable, the company faces heavy local and regional competition and has to negotiate with local broadcasters and distributors for its streaming TV licenses.

To attract new users, Netflix is emphasizing breadth of content and original programming such as the Emmy- and Golden Globe-winning political thriller “House of Cards.”

3. GLOBAL PRODUCT STRATEGIES

Developing global product strategies requires knowing what types of products or services are easily standardized and what are appropriate adaptation strategies.

PRODUCT STANDARDIZATION Some products cross borders without adaptation better than others, and consumer knowledge about new products is generally the same everywhere because perceptions have yet to be formed. Many leading Internet brands—such as Google, eBay, Twitter, and Facebook—made quick progress in overseas markets.

High-end products also benefit from standardization because quality and prestige often can be marketed similarly across countries. Culture and wealth factors influence how quickly a new product takes off in a country, though adoption and diffusion rates are becoming more alike across countries over time. Food and beverage marketers find it more challenging to standardize, of course, given widely varying tastes and cultural habits.66

A company may emphasize its products differently across markets. In its medical-equipment business, Philips traditionally reserved higher-end, premium products for developed markets and emphasized products with basic functionality and affordability in developing markets. Increasingly, however, the company is designing, engineering, and manufacturing locally in emerging markets like China and India.67

With a growing middle class in many emerging markets, many firms are assembling product portfolios to tap into different income segments. French food company Danone has many high-end healthy products, such as Dannon yogurt, Evian water, and Bledina baby food, but it also sells much lower priced products targeting consumers with “dollar-a-day” food budgets. In Indonesia, where average per-capita income is about US$10 a day, the company sells Milkuat, a 6 month shelf life neutral ph milk beverage. Danone now generates over 60% of its sales from growth markets (i.e. all except Western Europe), up from just 23% in 1996 (source: www .danone.com).68

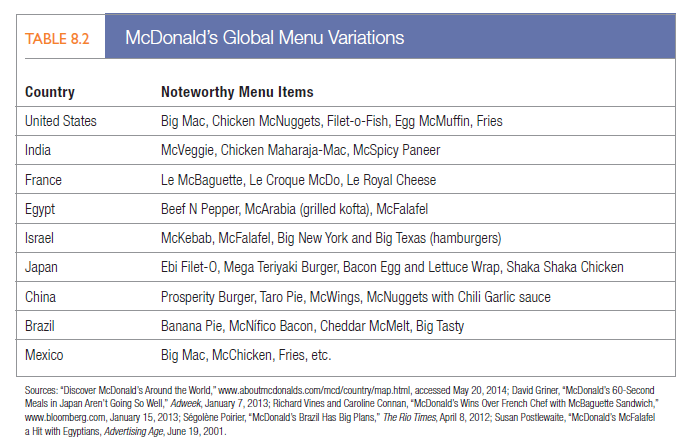

PRODUCT ADAPTATION STRATEGIES Warren Keegan has distinguished five product and communications adaptation strategies (see Figure 8.3).69 We review the product strategies here and the communication strategies in the next section.

Straight extension introduces the product in the foreign market without any change. Tempting because it requires no additional R&D expense, manufacturing retooling, or promotional modification, the strategy has been successful for cameras, consumer electronics, and many machine tools. In other cases, it has been a disaster. Campbell Soup Company lost an estimated $30 million introducing condensed soups in England; consumers saw expensive small-sized cans and didn’t realize water needed to be added.

Product adaptation alters the product to meet local conditions or preferences. Flexible manufacturing makes it easier to do so on several levels.

- A company can produce a regional version of its product. Dunkin’ Donuts has been introducing more regionalized products, such as Coco Leche donuts in Miami and sausage kolaches in Dallas.

- A company can produce a country version. Kraft blends different coffees for the British (who drink coffee with milk), the French (who drink it black), and Latin Americans (who want a chicory taste).

- A company can produce a city version—for instance, a beer to meet Munich’s or Tokyo’s tastes.

- A company can produce different retailer versions, such as one coffee brew for the Migros chain store and another for the Cooperative chain store, both in Switzerland.

Some companies have learned adaptation the hard way. The Euro Disney theme park, launched outside Paris in 1992, was harshly criticized as an example of U.S. cultural imperialism that ignored French customs and values, such as the serving of wine with meals. As one

Euro Disney executive noted, “When we first launched, there was the belief that it was enough to be Disney. Now we realize our guests need to be welcomed on the basis of their own culture and travel habits.” Renamed Disneyland Paris, the theme park eventually became one of Europe’s biggest tourist attraction—even more popular than the Eiffel Tower—by implementing a number of local touches.71

On the other hand, South Korea’s LG Electronics has found success in India by investing in local design and manufacturing facilities that helped it develop TVs with higher-quality speakers, refrigerators with brighter colors and smaller freezers, and microwaves with one-touch “Indian menu” functions, all reflecting Indian preferences.72 Product invention creates something new. It can take two forms:

- Backward invention reintroduces earlier product forms well adapted to a foreign country’s needs. A big hit in developing markets in Latin America, Mexico, and the Middle East, the powdered drink Tang has added local flavors like lemon pepper and soursop. Although its U.S. sales have fallen precipitously, its worldwide sales doubled from 2006 to 2011.73

- Forward invention creates a new product to meet a need in another country. Less-developed countries need low-cost, high-protein foods. Companies such as Quaker Oats, Swift, and Monsanto have researched their nutrition requirements, formulated new foods, and developed advertising to gain product trial and acceptance.

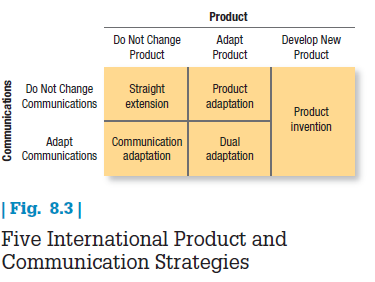

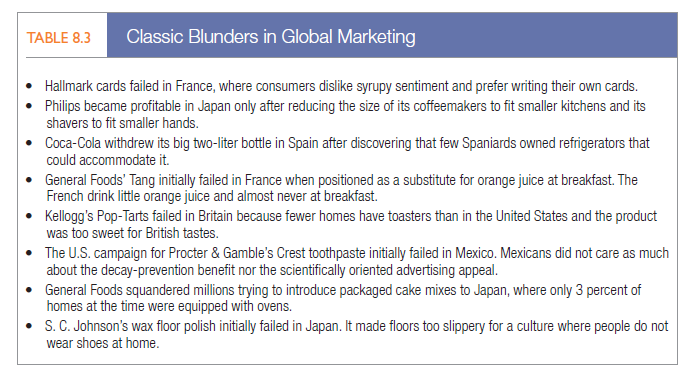

BRAND ELEMENT ADAPTATION When they launch products and services globally, marketers may need to change certain brand elements.74 Even a brand name may require a choice between phonetic and semantic translations.75 When Clairol introduced the “Mist Stick,” a curling iron, in Germany, it found that mist is slang for manure. In China, Coca-Cola and Nike have both found sets of Chinese characters that sounds broadly like their names but also offer some relevant meaning at the same time (“Can Be Tasty, Can Be Happy” and “Endurance Conquer,” respectively).76

Numbers and colors can take on special meaning in certain countries. The number four is considered unlucky throughout much of Asia because the Japanese word sounds like “death.” Some East Asian buildings skip not only the fourth floor but often every floor that has a four in it (14, 24, 40-49). Nokia doesn’t release phone models with the number four in them in Asia.77

Purple is associated with death in Burma and some Latin American nations, white is a mourning color in India, and in Malaysia green connotes disease. Red generally signifies luck and prosperity in China.78 Brand slogans or ad taglines sometimes need to be changed too:79

- When Coors put its brand slogan “Turn it loose” into Spanish, some read it as “suffer from diarrhea.”

- A laundry soap ad claiming to wash “really dirty parts” was translated in French-speaking Quebec to read “a soap for washing private parts.”

- Perdue’s slogan—“It takes a tough man to make a tender chicken”—was rendered into Spanish as “It takes a sexually excited man to make a chicken affectionate.”

Table 8.3 lists some other famous marketing mistakes in this area.

4. GLOBAL COMMUNICATION STRATEGIES

Changing marketing communications for each local market is a process called communication adaptation. If it adapts both the product and the communications, the company engages in dual adaptation.

Consider the message. The company can use one message everywhere, varying only the language and name.80 General Mills positions its Haagen-Dazs brand in terms of “indulgence,” “affordable luxury,” and “intense sensuality.” To communicate that message, it ran a 30-second TV spot called “Sensation,” with the tagline “Anticipated Like No Other” in markets all over the world, substituting only the voice-over in the language of each country.81

The second possibility is to use the same message and creative theme globally but adapt the execution. GE’s global “Ecomagination” ad campaign substitutes creative content in Asia and the Middle East to reflect cultural interests there. Even in the high-tech space, local adaptations may be necessary.82

The third approach, which Coca-Cola and Goodyear have used, consists of developing a global pool of ads from which each country selects the most appropriate. Finally, some companies allow their country managers to create country-specific ads—within guidelines, of course. The challenge is to make the message as compelling and effective as in the home market.

GLOBAL ADAPTATIONS Companies that adapt their communications wrestle with a number of challenges. They first must ensure their communications are legally and culturally acceptable. U.S. toy makers were surprised to learn that in many countries (Norway and Sweden, for example), no TV ads may be directed at children under 12. To foster a culture of gender neutrality, Sweden also now prohibits “sexist” advertising—a commercial that spoke of “cars for boys, princesses for girls” was criticized by government advertising regulators.83

A number of countries are taking steps to eliminate “super skinny” and airbrushed models in ads. Israel has banned “underweight” models from print and TV ads and runway shows. Models must have a body-mass index— a calculation based on height and weight—of greater than 18.5. According to that BMI standard, a female model who is 5 feet, 8 inches tall can weigh no less than 119 pounds.84

Firms next must check their creative strategies and communication approaches for appropriateness. Comparative ads, though acceptable and even common in the United States and Canada, are less frequent in the United Kingdom, unacceptable in Japan, and illegal in India and Brazil. The EU seems to have a very low tolerance for comparative advertising and prohibits bashing rivals in ads.

Companies also must be prepared to vary their messages’ appeal.85 In advertising its hair care products, Helene Curtis observed that middle-class British women wash their hair frequently, Spanish women less so. Japanese women avoid overwashing for fear of removing protective oils. Language can vary too, whether the local language, another such as English, or some combination.86

When the brand is at an earlier stage of development in its new market, consumer education may need to accompany brand development efforts. In launching Chik shampoo in rural areas of South India, where hair is washed with soap, CavinKare showed people how to use the product through live “touch and feel” demonstrations and free sachets at fairs.87

Personal selling tactics may need to change too. The direct, no-nonsense approach favored in the United States (“let’s get down to business” and “what’s in it for me”) may not work as well in Europe or Asia as an indirect, subtle approach.88

5. GLOBAL PRICING STRATEGIES

Multinationals selling abroad must contend with price escalation and transfer prices (and dumping charges). As part of those issues, two particularly thorny pricing problems are gray markets and counterfeits.

PRICE ESCALATION A Gucci handbag may sell for $120 in Italy and $240 in the United States. Why? Gucci must add the cost of transportation, tariffs, importer margin, wholesaler margin, and retailer margin to its factory price.

Price escalation from these added costs and currency-fluctuation risk might require the price to be two to five times as high for the manufacturer to earn the Marketers in Israel must observe the body-mass restrictions same profit. prohibiting overly-skinny models.

Companies have three choices for setting prices in different countries:

- Set a uniform price everywhere. PepsiCo might want to charge $1 for Pepsi everywhere in the world, but then it would earn quite different profit rates in different countries. Also, this strategy would make the price too high in poor countries and not high enough in rich countries.

- Set a market-based price in each country. PepsiCo would charge what each country could afford, but this strategy ignores differences in the actual cost from country to country. It could also motivate intermediaries in low-price countries to reship their Pepsi to high-price countries.89

- Set a cost-based price in each country. Here PepsiCo would use a standard markup of its costs everywhere, but this strategy might price it out of markets where its costs are high.

When companies sell their wares over the Internet, price becomes transparent and price differentiation between countries declines. Consider an online training course. Whereas the cost of a classroom-delivered day of training can vary significantly from the United States to France to Thailand, the price of an online-delivered day would be similar everywhere.

In another new global pricing challenge, countries with overcapacity, cheap currencies, and the need to export aggressively have pushed their prices down and devalued their currencies. Sluggish demand and reluctance to pay higher prices make selling in these markets difficult. Here is what IKEA did to compete in China’s challenging pricing market.90

IKEA When the Swedish home furnishings giant IKEA opened its first store in Beijing in 2002, local stores were selling copies of its designs at a fraction of IKEA’s prices. The only way to lure China’s frugal customers was to drastically slash prices. Western brands in China usually price products such as makeup and running shoes 20 percent to 30 percent higher than in their other markets, both to make up for China’s high import taxes and to give their products added cachet. By stocking its Chinese stores with Chinese-made products, IKEA has been able to slash prices as low as 70 percent below their level outside China. Western-style showrooms provide model bedrooms, dining rooms, and family rooms and suggest how to furnish them, an important consideration given home ownership in China has gone from practically zero in 1995 to about 70 percent today. Young couples are especially drawn to IKEA’s stylish, functional modern styles. Although it still contends with persistent knockoffs, IKEA maintains sizable stores in eight locations and aims to have 15 by 2015.

TRANSFER PRICES A different problem arises when one unit charges another unit in the same company a transfer price for goods it ships to its foreign subsidiaries. If the company charges a subsidiary too high a price, it may end up paying higher tariff duties, though it may pay lower income taxes in the foreign country. If the company charges its subsidiary too low a price, it can be accused of dumping, charging either less than its costs or less than it charges at home in order to enter or win a market. Various governments are watching for abuses and often force companies to charge the arm’s-length price—the price charged by other competitors for the same or a similar product.

When the U.S. Department of Commerce finds evidence of dumping, it can levy a dumping tariff on the guilty company. After much debate over government support for clean-energy products, the United States chose to set anti-dumping duties of 44.99 percent to 47.59 percent on wind towers produced in China and Vietnam and sent to the United States.91

GRAY MARKETS Many multinationals are plagued by the gray market, which diverts branded products from authorized distribution channels either in-country or across international borders. Often a company finds some enterprising distributors buying more than they can sell in their own country and reshipping the goods to another country to take advantage of price differences.

Gray markets create a free-rider problem, making legitimate distributors’ investments in supporting a manufacturer’s product less productive and selective distribution systems more intensive to reduce the number of gray market possibilities. They harm distributor relationships, tarnish the manufacturer’s brand equity, and undermine the integrity of the distribution channel. They can even pose risks to consumers if the product is damaged, relabeled, obsolete, without warranty or support, or just counterfeit. Because of their high prices, prescription drugs are often a gray market target, though U.S. government regulators are looking at the industry more closely after fake vials of Riche Holding AG’s cancer drug Avastin were shipped to U.S. doctors.92

Multinationals try to prevent gray markets by policing distributors, raising their prices to lower-cost distributors, or altering product characteristics or service warranties for different countries.93 3Com successfully sued several companies in Canada (for a total of $10 million) for using written and oral misrepresentations to get deep discounts on 3Com networking equipment. The equipment, worth millions of dollars, was to be sold to a U.S. educational software company and sent to China and Australia but instead ended up back in the United States.

One research study found that gray market activity was most effectively deterred when penalties were severe, manufacturers were able to detect violations or mete out punishments in a timely fashion, or both.94

COUNTERFEIT PRODUCTS As companies develop global supply chain networks and move production farther from home, the chance for corruption, fraud, and quality-control problems rises.95 Sophisticated overseas factories seem able to reproduce almost anything. Name a popular brand, and chances are a counterfeit version of it exists somewhere in the world.96

Counterfeiting is estimated to cost more than a trillion dollars a year. U.S. Customs and Border Protection seized $1.26 billion worth of goods in 2012; the chief culprits were China (81 percent) and Hong Kong (12 percent), and the chief products were apparel and accessories, followed by electronics, optical media, handbags and wallets, and watches and jewelry.97

At the Summer Olympics in London in 2012, the Egyptian Olympic team even admitted to buying fake Nike gear from a Chinese distributor because of the country’s dire economic situation. Once Nike found out what had happened, the company donated all the necessary training and village wear to the team.98

Fakes take a big bite of the profits of luxury brands such as Hermes, LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton, and Tiffany, but faulty counterfeits can literally kill people. Cell phones with counterfeit batteries, fake brake pads made of compressed grass trimmings, and counterfeit airline parts pose safety risks to consumers. Pharmaceuticals are especially worrisome. Toxic cough syrup in Panama, tainted baby formula in China, and fake teething powder in Nigeria have all led to the deaths of children in recent years.99

Virtually every product is vulnerable. Microsoft estimates that four-fifths of Windows OS software in China is pirated.100 As one anti-counterfeit consultant observed, “If you can make it, they can fake it.” Defending against counterfeiters is a never-ending struggle; some observers estimate that a new security system can be just months old before counterfeiters start nibbling at sales again.101

The Internet has been especially problematic. After surveying thousands of items, LVMH estimated 90 percent of Louis Vuitton and Christian Dior pieces listed on eBay were fakes, prompting the firm to sue. Manufacturers are fighting back online with Web-crawling software that detects fraud and automatically warns apparent violators without the need for any human intervention. Acushnet, maker of Titleist golf clubs and balls, shut down 75 auctions of knockoff gear in one day with a single mouse click.102

Web-crawling technology searches for counterfeit storefronts and sales by detecting domain names similar to legitimate brands and unauthorized Internet sites that plaster brand trademarks and logos on their homepages. It also checks for keywords such as cheap, discount, authentic, and factory variants, as well as colors that products were never made in and prices that are far too low.

6. GLOBAL DISTRIBUTION STRATEGIES

Too many U.S. manufacturers think their job is done once the product leaves the factory. They should instead note how the product moves within the foreign country and take a whole-channel view of distributing products to final users.

CHANNEL ENTRY Figure 8.4 shows three links between the seller and the final buyer. In the first, seller’s international marketing headquarters, the export department or international division makes Nike came to the rescue of the Egyptian Olympic team after they admit- decisions about channels and other marketing activities. The second ted buying fake Nike gear because of the country’s budgetary problems.

link, channels between nations, gets the products to the borders of the foreign nation. Decisions made in this link include the types of intermediaries (agents, trading companies), type of transportation (air, sea), and financing and risk management. The third link, channels within foreign nations, gets products from their entry point to final buyers and users.

When multinationals first enter a country, they prefer to work with local distributors with good local knowledge, but friction often arises later.103 The multinational complains that the local distributor doesn’t invest in business growth, doesn’t follow company policy, and doesn’t share enough information. The local distributor complains of insufficient corporate support, impossible goals, and confusing policies. The multinational must choose the right distributors, invest in them, and set up performance goals to which they can both agree.104

CHANNEL DIFFERENCES Distribution channels across countries vary considerably. To sell consumer products in Japan, companies must work through one of the most complicated distribution systems in the world. They sell to a general wholesaler, who sells to a product wholesaler, who sells to a product-specialty wholesaler, who sells to a regional wholesaler, who sells to a local wholesaler, who finally sells to retailers. All these distribution levels can make the consumer’s price double or triple the importer’s price. Taking these same consumer products to tropical Africa, the company might sell to an import wholesaler, who sells to several jobbers, who sell to petty traders (mostly women) working in local markets.

Another difference is the size and character of retail units abroad. Large-scale retail chains dominate the U.S. scene, but much foreign retailing is in the hands of small, independent retailers. Millions of Indian retailers operate tiny shops or sell in open markets. Markups are high, but the real price comes down through haggling. Incomes are low, most homes lack storage and refrigeration, and people shop daily for whatever they can carry home on foot or bicycle. In India, people often buy one cigarette at a time. Breaking bulk remains an important function of intermediaries and helps perpetuate long channels of distribution, a major obstacle to the expansion of large-scale retailing in developing countries.

Nevertheless, retailers are increasingly moving into new global markets, offering firms the opportunity to sell across more countries and creating a challenge to local distributors and retailers.105 Frances Carrefour, Germany’s Aldi and Metro, and United Kingdom’s Tesco have all established global positions. But even some of the worlds most successful retailers have had mixed success abroad. Despite concerted efforts and earlier success in Latin America and China, Walmart had to withdraw from both the German and South Korean markets after heavy losses. Walmart now earns a quarter of its revenue overseas by being more sensitive to local market needs in different countries.106

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

Excellent post! We will be linking to this particularly great article on our site. Keep up the great writing.

I used to be able to find good information from your blog posts.

There’s definately a great deal to find out about this topic. I really like all of the points you’ve made.

Pretty! This has been an extremely wonderful post. Thanks for supplying these details.

I’m very pleased to uncover this web site. I want to to thank you for your time just for this fantastic read!! I definitely really liked every little bit of it and I have you saved as a favorite to check out new things on your web site.

Great web site you’ve got here.. Itís hard to find excellent writing like yours these days. I truly appreciate people like you! Take care!!