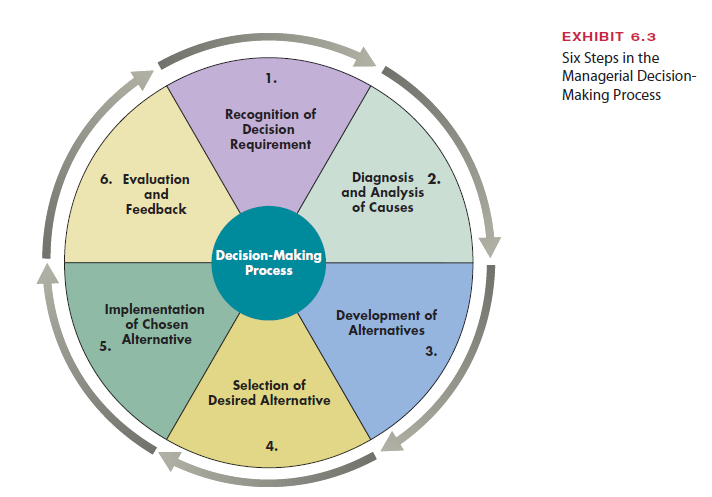

Whether a decision is programmed or nonprogrammed and regardless of managers’ choice of the classical, administrative, or political model of decision making, six steps typically are associated with effective decision processes. These steps are summarized in Exhibit 6.3.

1. RECOGNITION OF DECISION REQUIREMENT

Managers confront a decision requirement in the form of either a problem or an opportu- nity. A problem occurs when organizational accomplishment is less than established goals. Some aspect of performance is unsatisfactory. An opportunity exists when manag- ers see potential accomplishment that exceeds specified current goals. Managers see the possibility of enhancing performance beyond current levels. Oprah Winfrey’s agent saw opportunities for her that she never dreamed of, as described in the Spotlight on Collaboration box.

Awareness of a problem or opportunity is the first step in the decision sequence and requires surveillance of the internal and external environ- ment for issues that merit executive attention.36 This process resembles the military concept of gathering intelligence. Managers scan the world around them to determine whether the organization is satisfactorily pro- gressing toward its goals.

Some information comes from periodic financial reports, performance reports, and other sources that are designed to discover problems before they become too serious. Managers also take advantage of informal sources. They talk to other managers, gather opinions on how things are going, and seek advice on which problems should be tackled or which opportunities embraced.37 Recognizing decision requirements is difficult because it often means integrating bits and pieces of information in novel ways. For example, the failure of U.S. intelligence leaders to recognize the imminent threat of Al Qaeda prior to the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks has been attributed partly to the lack of systems that could help leaders put together myriad snippets of information that pointed to the problem.38

2. DIAGNOSIS AND ANALYSIS OF CAUSES

After a problem or opportunity comes to a manager’s attention, the understanding of the situation should be refined. Diagnosis is the step in the decision-making process in which managers analyze under- lying causal factors associated with the decision situation. Managers make a mistake here if they jump right into generating alternatives without first exploring the cause of the problem more deeply.

Kepner and Tregoe, who conducted extensive studies of manager de- cision making, recommend that managers ask a series of questions to specify underlying causes, including the following:

- What is the state of disequilibrium affecting us?

- When did it occur?

- Where did it occur?

- How did it occur?

- To whom did it occur?

- What is the urgency of the problem?

- What is the interconnectedness of events?

- What result came from which activity?39

Such questions help specify what actually happened and why. Managers at General Motors are struggling to diagnose the underlying factors in the company’s recent troubles. The problem is an urgent one, with sales, profits, market share, and the stock price all plummeting, and the giant corporation on the verge of bankruptcy. Managers are examin- ing the multitude of problems facing GM, tracing the pattern of the decline, and looking at the interconnectedness of issues such as changing consumer tastes in vehicles, surging gas prices that make trucks and SUVs less appealing, the rising burden of retiree benefits promised to workers in more profitable times, increased competition and the growth of auto manufacturing in low-cost countries such as China, excess factory capacity and high costs, poor headquarters planning, and weak control systems that allowed the company to drift further and further into crisis.40

3. DEVELOPMENT OF ALTERNATIVES

After the problem or opportunity has been recognized and analyzed, decision makers begin to consider taking action. The next stage is to generate possible alternative solutions that will respond to the needs of the situation and correct the underlying causes. Studies find that limiting the search for alternatives is a primary cause of decision failure in organizations.41

For a programmed decision, feasible alternatives are easy to identify and, in fact, usu- ally are already available within the organization’s rules and procedures. Nonpro- grammed decisions, however, require developing new courses of action that will meet the company’s needs. For decisions made under conditions of high uncertainty, manag- ers may develop only one or two custom solutions that will satisfice for handling the problem.

Decision alternatives can be thought of as the tools for reducing the difference between the organization’s current and desired performance. For example, to improve sales at fast- food giant McDonald’s, executives considered alternatives such as using mystery shoppers and unannounced inspections to improve quality and service, motivating demoralized fran- chisees to get them to invest in new equipment and programs, taking R&D out of the test kitchen and encouraging franchisees to help come up with successful new menu items, and closing some stores to avoid cannibalizing its own sales.42

4. SELECTION OF DESIRED ALTERNATIVE

After feasible alternatives are developed, one must be selected. The decision choice is the selection of the most promising of several alternative courses of action. The best alterna- tive is one in which the solution best fits the overall goals and values of the organization and achieves the desired results using the fewest resources.43 The manager tries to select the choice with the least amount of risk and uncertainty. Because some risk is inherent for most nonprogrammed decisions, managers try to gauge prospects for success. Under con- ditions of uncertainty, they might rely on their intuition and experience to estimate whether a given course of action is likely to succeed. Basing choices on overall goals and values can also effectively guide the selection of alternatives. Recall from Chapter 2 Valero Energy’s decision to keep everyone on the payroll after Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast, while other refineries shut down and laid off workers. For Valero managers, the choice was easy based on values of putting employees first. Valero’s values-based decision making helped the company zoom from number 23 to number 3 on Fortune magazine’s list of best companies to work for—and enabled Valero to get back to business weeks faster than competitors.44

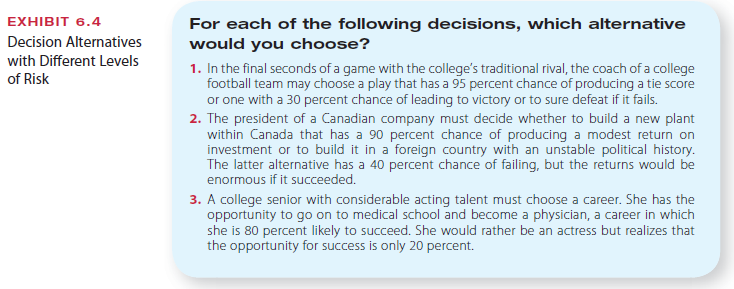

Choosing among alternatives also depends on managers’ personality factors and willing- ness to accept risk and uncertainty. For example, risk propensity is the willingness to undertake risk with the opportunity of gaining an increased payoff. The level of risk a manager is willing to accept will influence the analysis of cost and benefits to be derived from any decision. Consider the situations in Exhibit 6.4. In each situation, which alterna- tive would you choose? A person with a low-risk propensity would tend to take assured moderate returns by going for a tie score, building a domestic plant, or pursuing a career as a physician. A risk taker would go for the victory, build a plant in a foreign country, or em- bark on an acting career.

5. IMLEMENTATION OF CHOSEN ALTERNATIVE

The implementation stage involves the use of managerial, administrative, and persuasive abilities to ensure that the chosen alternative is carried out. This step is similar to the idea of strategic implementation. The ultimate success of the chosen alternative depends on whether it can be translated into action.45 Sometimes an alternative never becomes reality because managers lack the resources or energy needed to make things happen. Implemen- tation may require discussion with people affected by the decision. Communication, moti- vation, and leadership skills must be used to see that the decision is carried out. When em- ployees see that managers follow up on their decisions by tracking implementation success, they are more committed to positive action.46

At Boeing Commercial Airplanes, CEO Alan R. Mulally engineered a remarkable turnaround by skillfully implementing decisions that reduced waste, streamlined produc- tion lines, and moved Boeing into breakthrough technologies for new planes.47 If managers lack the ability or desire to implement decisions, the chosen alternative cannot be carried out to benefit the organization.

6. EVALUATION AND FEEDBACK

In the evaluation stage of the decision process, decision makers gather information that tells them how well the decision was implemented and whether it was effective in achieving its goals. For example, Tandy executives evaluated their decision to open computer centers for businesses, and feedback revealed poor sales performance. Feedback indicated that im- plementation was unsuccessful, and computer centers were closed so Tandy could focus on its successful Radio Shack retail stores.

Feedback is important because decision making is a continuous, neverending process. Decision making is not completed when an executive or board of directors votes yes or no. Feedback provides decision makers with information that can precipitate a new decision cycle. The decision may fail, thus generating a new analysis of the problem, evaluation of alternatives, and selection of a new alternative. Many big problems are solved by trying several alternatives in sequence, each providing modest improvement. Feedback is the part of monitoring that assesses whether a new decision needs to be made.

To illustrate the overall decision-making process, including evaluation and feedback, we can look at the decision to introduce a new deodorant at Tom’s of Maine.

Tom’s of Maine’s decision illustrates all the decision steps, and the process ultimately ended in success. Strategic decisions always contain some risk, but feedback and follow-up decisions can help get companies back on track. By learning from their decision mistakes, managers and companies can turn problems into opportunities.

Source: Daft Richard L., Marcic Dorothy (2009), Understanding Management, South-Western College Pub; 8th edition.

I’m not that much of a internet reader to be honest but your sites really nice, keep it up! I’ll go ahead and bookmark your website to come back in the future. Many thanks

Your style is so unique compared to many other people. Thank you for publishing when you have the opportunity,Guess I will just make this bookmarked.2