A letter of credit (L/C) is a document in which a bank or other financial institution assumes liability for payment of the purchase price to the seller on behalf of the buyer. The bank could deal directly or through the intervention of a bank in the seller’s country. In all types of letters of credit, the buyer arranges with a bank to provide finance for the exporter in exchange for certain documents. The bank makes its credit available to its client, the buyer, in consideration of a security that often includes a pledge of the documents of title to the goods, placement of funds in advance, or a pledge to reimburse with a commission (Reynolds, 2003). The essential feature of this method, and its value to an exporter of goods, is that it superimposes upon the credit of the buyer the credit of a bank, often one carrying on business in the seller’s country. The letter of credit is a legally enforceable commitment by a bank to pay money upon the performance of certain conditions stipulated therein to the seller (exporter or beneficiary) for the account of the buyer (importer or applicant).

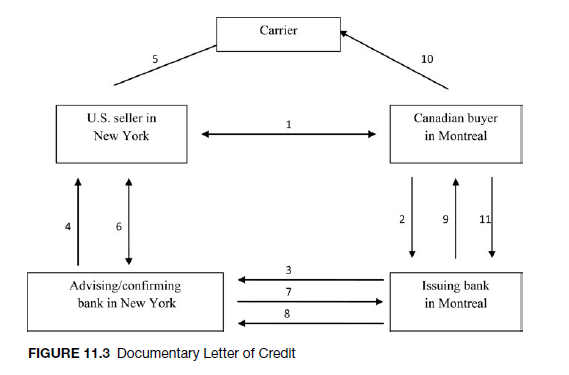

A letter of credit (L/C) is considered an export or import L/C depending on the party. The same letter of credit is considered an export L/C by the seller and an import L/C by the buyer. The steps involved in Figure 11.3 are as follows:

- The Canadian buyer in Montreal contracts with the U.S. seller in New York. The agreement provides for the payment to be financed by means of a confirmed, irrevocable documentary credit for goods delivered CIF, port of Montreal.

- The Canadian buyer applies to its bank (issuing bank), which issues the letter of credit with the U.S. seller as beneficiary.

- Issuing bank sends the letter of credit to an advising bank in the United States, which also confirms the letter of credit.

- The advising bank notifies the U.S. seller that a letter of credit has been issued on its behalf (confirmed by the advising bank) and is available on presentation of documents.

- The U.S. seller scrutinizes the credit. When satisfied that the stipulations in the credit can be met, the U.S. seller arranges for shipment and prepares the necessary documents, that is, commercial invoice, bill of lading, draft, insurance policy, and certificate of origin. Amendments may be necessary in cases in which the credit improperly describes the merchandise.

- After shipment of merchandise, the U.S. seller submits the relevant documents to the advising/confirming bank for payment. If the documents comply, the advising/confirm- ing bank pays the seller. (If the L/C provides for acceptance, the bank accepts the draft, signifying its commitment to pay the face value at maturity to the seller or bona fide holder of the draft; this is called acceptance L/C. In straight L/C, payment is made by the issuing bank or the bank designated in the credit at a determinable future date. If the credit provides for negotiation at any bank, it is known as negotiable L/C).

- The advising/confirming bank sends documents plus settlement instructions to the issuing bank.

- After inspecting the documents for compliance with instructions, the issuing bank reim- burses/remits the proceeds to the advising/confirming bank.

- The issuing bank gives the documents to the buyer and presents the term draft for acceptance. With a sight draft, the issuing bank will be paid by the buyer on presentation of documents.

- The buyer arranges for clearance of the merchandise, that is, gives up the bill of lading and takes receipt of goods.

- The buyer pays the issuing bank on or before the draft maturity date.

Issuing banks often verify receipt of full details of the L/C by the advising bank. This is done by using a private test code arrangement between banks. Credits are opened and forwarded to the advising/confirming bank by mail, telex, or cable. Issuing banks can also open credits by using the SWIFT system (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications), which allows for faster transmission time. It also allows member banks to use automatic authentication (verification) of messages (Ruggiero, 1991).

The letter of credit consists of four separate and distinct bilateral contracts: (1) a sales contract between the buyer and the seller; (2) a credit and reimbursement contract between the buyer and the issuing bank, providing for the issuing bank to establish a letter of credit in favor of the seller and for reimbursement by the buyer; (3) a letter- of-credit contract between the issuing bank and the beneficiary (exporter), attesting that the bank will pay the seller on presentation of specified documents; and (4) the confirmed advice, which also signifies a contract between the advising/confirming bank and the seller, attesting that the bank will pay the seller on presentation of specified documents.

When the letter of credit is revocable, the issuing bank could amend or cancel the credit at any time after issue without consent from or notice to the seller. Revocable L/Cs are seldom used in international trade except in cases of trade between parent and subsidiary companies because they do not provide sufficient protection to the seller. Under the Uniform Customs and Practice for Documentary Credits (UCP), letters of credit are deemed irrevocable even if there is no indication to that effect (ICC, 2007). Irrevocable credits cannot be amended or canceled before their expiry date without the express consent of all parties to the credit. The terms “revocable” and “irrevocable” refer only to the issuing bank.

In cases in which sellers do not know of or have little confidence in the financial strength of the buyer’s country or the issuing bank, they often require a bank in their country to guarantee payment (i.e., confirm the L/C).

There are several advantages of using letters of credit. They accommodate the competing desires of the seller and overseas customer. The seller receives payment on presentation of documents to the bank after shipment of goods, unlike open-account sales or documentary collection. In cases in which the advising bank accepts the L/C for payment at a determinable future date, the seller can discount the L/C before maturity. Buyers also avoid the need to make prepayment or to establish an escrow account. Letters of credit also ensure that payment is not made until the goods are placed in possession of a carrier and that specified documents are presented to that effect (Shapiro, 2006).

One major disadvantage with an L/C for the buyer is that issuing banks often require cash or other collateral before they open an L/C, unless the buyer has a satisfactory credit rating. This could tie up the available credit line. In certain countries, buyers are also required to make a prior deposit before establishing an L/C. Letters of credit are complex transactions between different parties, and the smallest discrepancy between documents could require an amendment of the terms or lead to the invalidation of the credit. This may expose the seller to a risk of delay in payment or nonpayment in certain cases.

A letter of credit is a documentary payment obligation, and banks are required to pay or agree to pay on presentation of appropriate documents as specified in the credit. This payment obligation applies even if a seller ships defective or nonexistent goods (empty crates/ boxes). The buyer then has to sue for breach of contract. The interests of the buyer can be protected by structuring the L/C to require, as a condition of payment, the following:

- The presentations of a certificate of inspection executed by a third party certifying that the goods shipped conform to the terms of the contract of sale. If the goods are defective or nonconforming to the terms of the contract, the third party will refuse to sign the certificate and the seller will not receive payment. In such cases, it is preferable to use a revocable L/C.

- The presentation of a certificate of inspection executed or countersigned by the buyer. It is preferable to use a revocable L/C to allow the bank to cancel the credit.

- A reciprocal standby L/C issued in favor of the buyer in which the latter could draw on this credit and obtain a return of the purchase price if the seller shipped nonconforming goods (McLaughlin, 1989).

1. Governing Law

The rights and duties of parties to a letter of credit issued or confirmed in the United States are determined by reference to three different sources:

- The Uniform Commercial Code (UCC): The basic law on letter of credit is codified in article 5-101 to 5-117 of the Uniform Commercial Code. This article has been adopted in all states of the Union. However, some states (New York, Missouri, Alabama) have introduced an amendment providing that article 5 will not apply if the letter of credit is subject, in whole or in part, to the Uniform Customs and Practice for Documentary Credits.

- The Uniform Customs and Practice for Documentary Credits (UCP): Parties to the letter of credit frequently agree to be governed by the rules of the UCP, which is a result of collaboration among the International Chamber of Commerce, the United Nations, and many international trade banks. The UCP is periodically revised to take into account new developments in international trade and credit (the latest revision was in 2007) (see International Perspective 11.2). The UCC and UCP provisions on letters of credit complement each other in many areas. Under both the UCC and the UCP, the terms of the credit can be altered by agreement of the parties.

- General principles of law: In cases in which the UCC or UCP provisions are not sufficient to resolve a dispute, courts apply general principles of law insofar as they do not conflict with the governing law (UCC or UCP) or agreement of the parties.

2. Role of Banks Under Letters of Credit

The buyer’s bank issues the letter of credit at the request of the buyer. The details of the credit are normally specified by the buyer. Since the seller wants a local bank available to which the seller can present the letter of credit for payment, an additional bank often becomes involved in the transaction. The second bank usually either “advises” or “confirms” the letter of credit. A bank that advises on the L/C gives notification of the terms and conditions of the credit issued by another bank to the seller. It assumes no liability for paying the letter of credit. Its only obligation is to ensure that the beneficiary (seller) is advised and the credit delivered and to ensure the apparent authenticity of the credit.

An issuing bank may also request a bank to confirm the letter of credit. A confirming bank promises to honor a letter of credit already issued by another bank and becomes directly obligated to the beneficiary (seller), as though it had issued the letter of credit itself. It will pay, accept, or negotiate a letter of credit upon presentation of specific documents that comply with the terms and conditions of the credit. A confirming bank is entitled to reimbursement by the issuing bank, assuming that the latter’s instructions have been properly executed. It, however, faces the risk of nonpayment if the issuing bank or the buyer is unable or unwilling to pay the confirming bank, in which case it will be left with title to the goods and obliged to liquidate them to offset its losses.

Both the confirming and the issuing banks have an obligation to the exporter (beneficiary) and the buyer to act in good faith and with reasonable care in examining the documents. The basic rule pertaining to a bank’s liability to a beneficiary is that the bank should honor the L/C if the documents presented comply with the terms of the credit. The following circumstances cannot be used by banks as a basis to dishonor (refusal to pay or accept a draft) letters of credit:

- Dishonor to serve the buyer s interests: In this case, claims are made by a bank’s customer (buyer) that the beneficiary has breached the sales contract or that the underlying agreement has been modified or amended in some way in the face of complying documents. This includes cases of dishonor based on the bank’s knowledge or reasonable belief that the goods do not conform to the underlying contract of sale.

- Dishonor to serve the bank’s own interests: This occurs when the sole reason for dishonor is the bank’s belief that it would not obtain reimbursement from its insolvent customer. This involves situations in which the buyer becomes insolvent after the L/C is issued and before the beneficiary’s draft is honored.

- Dishonor after express waiver of a particular discrepancy: In this case, a bank dishonors an L/C after it has expressly agreed to disregard a particular discrepancy.

- Dishonor without giving the beneficiary an opportunity to correct the discrepancy: If the issuing bank decides to refuse the documents, it must give notice to that effect, stating the discrepancy without delay, and must also state whether it is holding the documents at the disposal of and returning them to the remitting bank or beneficiary, as the case may be (Arzt, 1991; Rosenblith, 1991).

Banks may properly dishonor a letter of credit in cases of fraud or forgery, even if the documents presented to the beneficiary appear to comply with the terms of credit. This assumes that there are no innocent parties involved in the presentation of the letter of credit to the bank. Banks are subject to two principles in the conduct of their letter-of-credit transactions: the independent principle and the rule of strict compliance.

2.1. The Independent Principle

The letter of credit is separate from and independent of other contracts relating to the transaction. Each of the four contracts in a letter-of-credit transaction is entirely independent. It is irrelevant to the bank whether the seller/buyer has fully carried out its part of the contract with the buyer/seller. The bank’s duty is to establish whether the stipulated documents have been presented in order to pay (accept to pay) the exporter. It is not the bank’s duty to ascertain whether the goods mentioned in the documents have been shipped or whether they conform to the terms of the contract. Article 4 of the UCP states:

Credits by their nature are separate transactions from the sales or other contract(s) on which they may be based and banks are in no way concerned with or bound by such contract(s), even if any reference whatsoever to such contract(s) is included in the credit. (ICC, 2007, p. 5)

The independent principle is subject to a fraud exception. A bank can refuse payment if it has been informed that there has been fraud or forgery in connection with the letter- of-credit transaction and the person presenting the documents is not a holder in due course (as third party who took the draft for value, in good faith, and without knowledge of the fraud). In one case, for example, a buyer notified the issuing bank not to pay the seller under the letter of credit, alleging that the seller had intentionally shipped fifty crates of rubbish in place of fifty crates of bristles. The bank’s refusal of payment was accepted by the court as justifiable in view of fraud in the underlying transaction (Ryan, 1990). U.S. courts have held in several cases that banks are justified in dishonoring L/Cs when the documents are forged or fraudulent. Banks assume no liability or responsibility for the form, sufficiency, accuracy, genuineness, or legal effect of any documents. The obligation to honor an irrevocable L/C exists provided the stipulated documents are presented. In credit operations, all parties concerned deal in documents and not in the goods to which the documents relate. Thus, when the L/C is governed by the UCP, it appears that the bank must pay, regardless of any underlying fraud. A bank would, however, be liable for the money paid out if it participated in the fraud.

2.2. The Rule of Strict Compliance

The general rule is that an exporter cannot compel payment unless it strictly complies with the conditions specified in the credit (Rosenblith, 1991). When conforming documents are presented, the advising bank must pay, the issuing bank must reimburse, and the buyer is obliged to pay the issuing bank. In certain cases, courts have refused to recognize the substantial-compliance argument by banks to recover their payments from buyers (unless it involves minor spelling errors or insignificant additions or abbreviations in drafts) (Rubenstein, 1994). The reason behind the doctrine of strict compliance is that the advising bank is an agent of the issuing bank and the latter is a special agent of the buyer. This means that banks have limited authority and have to bear the commercial risk of the transaction if they act outside the scope of their mandate (Barnes, 1994; Macintosh, 1992). In addition, in times of falling demand, the buyer may be tempted to reject documents that the bank accepted, alleging that they are not in strict compliance with the terms of the credit.

Two assumptions underlie the doctrine of strict compliance:

- Linkage of documents: The documents (bill of lading, draft, invoice, insurance certificate) are linked by an unambiguous reference to the same merchandise.

- Description of goods: The goods must be fully described in the invoice, but the same details are not necessary in all the other documents. What is important is that the documents, when taken together, contain the particulars required under the L/C. This means that the invoice could include more details than the bill of lading as long as the enlarged descriptions are essentially consistent with those contained in the bill of lading (Murray, 2007).

3. Discrepancies

Discrepancies occur when documents submitted contain language or terms different from those in the letter of credit or some other apparent irregularity (International Perspectives 11.3 and 11.4). Most discrepancies occur because the exporter does not present all the documents required under the letter of credit or because the documents do not strictly conform to the L/C requirements (Reynolds, 2003).

Example: Dushkin Bank issued an irrevocable L/C on behalf of its customer (buyer), John Textiles, Inc. It promised to honor a draft of KG Company (exporter) for $250,000, covering shipment of “100% Acrylic Yarn.” KG Company presented its draft with a commercial invoice describing the merchandise as “Imported Acrylic Yarns.”

Discrepancy: The description of the goods in the invoice does not match that stated in the letter of credit. Dushkin Bank could refuse to honor the draft and return the documents to the exporter.

To receive payment under the credit, the exporter must present documents that are in strict accord with the terms of the letter of credit. It is estimated that more than 80 percent of documents presented under L/Cs contain some discrepancy.

There are three types of discrepancies:

- Accidental discrepancies: These are discrepancies that can easily be corrected by the exporter (beneficiary) or the issuing bank. Such discrepancies include typographical errors, failure to state the L/C number, errors in arithmetic, and improper endorsement or signature on the draft. Once these discrepancies are corrected (within a reasonable period of time), the bank will accept the documents and pay the exporter.

- Minor discrepancies: These are minor errors in documents that contain the essential particulars required in the L/C and can be corrected by obtaining a written waiver from the buyer. Such errors include failure to legalize documents, nonpresentation of all documents required under the L/C, and discrepancies between the wording on the invoice and that in the L/C. Once these discrepancies are waived by the buyer, the transaction will proceed as anticipated.

- Major discrepancies: These are discrepancies that fundamentally affect the essential nature of the L/C. Certain discrepancies cannot be corrected under any circumstances: presentation of documents after the expiry date of the L/C, shipment of merchandise

later than the specified date under the L/C, or expiration of the L/C. However, other major discrepancies can be corrected by an amendment of the L/C. Amendments require the approval of the issuing bank, the confirming bank (in the case of a confirmed L/C), and the exporter. Examples of discrepancies that can be amended include an incorrect bill of lading, a draft in excess of the amount specified in the credit, and partial shipments not allowed under the credit.

Discrepancies that can be corrected (accidental, minor, and certain major discrepancies) must be rectified within a reasonable period of time after shipment and before the expiry of the letter of credit. Most letters of credit require that the documents be submitted within a reasonable period of time after the date of the bill of lading. If no time is specified, the UCP requires submission of shipping documents by beneficiary to banks no later than twenty-one days after the date of shipment and, in any event, no later than the expiry date of the credit.

In cases in which the buyer is looking for an excuse to reject the documents (e.g., when the price of the product is falling or the product is destroyed on shipment), the buyer may not accede to a waiver or amendment of the discrepancy or may do so in consideration for a huge discount off the contract price. The buyer could also delay correction, in which case the exporter loses the use of the proceeds for a certain period of time. Besides incurring further bank charges to correct the discrepancy, the seller also faces the risk that the credit will expire before the discrepancies are corrected.

When the discrepancy stands (the discrepancy cannot be corrected or the buyer refuses to waive or amend the terms of the credit), the seller can still attempt to obtain payment by requesting the bank to obtain authority to pay or send the documents for collection (documentary collection) outside the terms of the L/C. If the buyer refuses to accept the documents, the bank will not pay the seller (exporter), and the exporter has to either find a buyer abroad or have the merchandise returned. If the confirming/issuing bank accepts documents that contain a discrepancy, then it cannot seek reimbursement from its respective customers (issuing bank/buyer, respectively) (International Perspective 11.4).

When the issuing bank decides to refuse the document, it must notify the party from which it obtained the document (the remitting bank or the exporter) without delay, stating the reasons for the rejection and whether it holds the documents at the disposal of or is returning them to the presenter.

Source: Seyoum Belay (2014), Export-import theory, practices, and procedures, Routledge; 3rd edition.

Outstanding post, I believe people should learn a lot from this blog its very user genial.

Very well written story. It will be supportive to everyone who usess it, including me. Keep doing what you are doing – looking forward to more posts.