The Ciba-Geigy Company in the late 1970s and early 1980s was a Swiss multidivisional, geographically decentralized chemical company with several divisions dealing with pharmaceuticals, agricultural chemicals, industrial chemicals, dyestuffs, and some technically based consumer products. It eventually merged with a former competitor, Sandoz, to become what is today Novartis. I was originally asked to give some talks at their 1979 annual meeting of top executives on the topic of innovation and creativity, and this encounter evolved into a variety of consulting activities that lasted into the mid-1980s.

1. Artifacts-Encountering Ciba-Geigy

My initial encounter with this company was through a telephone call from its head of management development, Dr. Jurg Leupold, inquiring whether I would be willing to give a talk to their annual meeting in Switzerland.

Ciba-Geigy ran annual meetings of their top forty to fifty executives worldwide and had a tradition of inviting one or two outsiders to the three-day meetings held at a Swiss resort. The purpose was to stimulate the group by having outside lecturers present on topics of interest to the company. Dr. Leupold asked me to give lectures and do some structured exercises to improve the group ’s understanding of creativity and to increase “innovation” and “leadership” in the company. Prior to the annual meeting, I was to visit the company headquarters to be briefed, to meet some other key executives—especially Dr. Sam Koechlin the CEO—and to review the other material that was to be presented at the annual meeting. I got the impression that things were highly organized and carefully planned.

I was “briefed” by further phone contacts and learned that the company was run by a board of directors and an internal executive committee of nine people who were legally accountable as a group for company decisions. The chairman of this executive committee, Sam Koechlin, functioned as the CEO, but the committee made most decisions by consensus.

Each member of the committee had oversight responsibility for a division, a function, and a geographic area, and these responsibilities rotated from time to time. Both Ciba and Geigy had long histories of growth and had merged in 1970. The merger was considered to be a success, but there were still strong identifications with the original companies, according to many managers. The CEO of Novartis when I asked him in 2006 how the Ciba-Geigy/Sandoz merger went said: “That merger is going fine but I still have Ciba people and Geigy people!”

My first visit to Ciba – Geigy offered a sharp contrast to what I had encountered at DEC. I was immediately struck by the formality as symbolized by large gray stone buildings, heavy doors that were always closed, and stiff uniformed guards in the main lobby. This spacious, opulent lobby was the main passageway for employees to enter the inner compound of office buildings and plants. It had high ceilings, large heavy doors, and a few pieces of expensive modern furniture in one corner to serve as a waiting area.

I reacted differently to the Ciba-Geigy and DEC environments. I liked the DEC environment more. In doing a cultural analysis, a person’s reactions are themselves artifacts of the culture that must be acknowledged and taken into account. It is undesirable to present any cultural analysis with total objectivity because not only would this be impossible, but a person’s emotional reactions and biases are also primary data to be analyzed and understood.

Upon entering the Ciba-Geigy lobby, I was asked by the uniformed guard to check in with another guard who sat in a glassed-in office. I had to give my name and state where I was from and whom I was visiting. The guard then asked me to take a seat while he did some telephoning and to wait until an escort could take me to my appointed place. As I sat and waited, I noticed that the guard seemed to know most of the employees who streamed through the lobby or went to elevators and stairs leading from it. I had the distinct feeling that any stranger would have been spotted immediately and would have been asked to report as I had been.

Dr. Leupold’s secretary arrived in due course and took me up the elevator and down a long corridor of closed offices. Each office had a tiny nameplate that could be covered over by a hinged metal plate if the occupant wanted to remain anonymous. Above each office was a light bulb, some of which showed red and some green. I asked on a subsequent visit what this meant and was told that if the light was out the person was not in, if it was green it was okay to knock, whereas red meant that the person did not want to be disturbed under any circumstances.

We went around a corner and down another such corridor and did not see another soul during the entire time. When we reached Dr. Leupold ’s office, the secretary knocked discreetly. When he called to come in, she opened the door, ushered me in, then went to her own office and closed the door. I was offered some tea or coffee, which was brought by the secretary on a large formal tray with china accompanied by a small plate of excellent cookies. I mention that they were “excellent” because it turned out that good food was very much part of Ciba-Geigy’s presented identity. Whenever I visited offices in later years in Paris and London, I was always taken to three star restaurants.

Following our meeting, Dr. Leupold took me to the executive dining room in another building, where we again passed guards. This was the equivalent of a first-class restaurant, with a hostess who clearly knew everyone, reserved tables, and provided discreet guidance on the day’s specials. Aperitifs and wine were offered with lunch, and the whole meal took almost two hours. I was told that there was a less fancy dining room in still another building and an employee cafeteria as well, but that this dining room clearly had the best food and was the right place for senior management to conduct business and to bring visitors. Whereas in DEC kitchens and food were used as vehicles to get people to interact with each other, in Ciba-Geigy, food, drink, and graciousness had some additional symbolic meaning, possibly having to do with status and rank.

Various senior officers of the company were pointed out to me, and I noticed that whenever anyone greeted another, it was always with their formal titles, usually Dr. This or Dr. That. Observable differences in deference and demeanor made it fairly easy to determine who was superior to whom in the organization. It was also obvious that the tables in the room were assigned to executives on the basis of status and that the hostess knew exactly the relative status of all her guests.

Throughout my consultation, in moving around the company I always felt a hushed atmosphere in the corridors; a slower, more deliberate pace; and much more emphasis on planning, schedules, and punctuality. Whereas in DEC I got the impression of frantic activity to make the most of what time there was, in Ciba- Geigy time was carefully managed to maintain order. If I had an appointment with a manager at 2 P.M., the person I was with just prior to that meeting would start walking down the hall with me at 1:58 so that we would arrive almost exactly on the dot. Only rarely was I kept waiting if I arrived on time, and if I was even a few minutes late, I had the strong sense that I had to apologize and explain.

Ciba-Geigy managers came across as very serious, thoughtful, deliberate, well prepared, formal, and concerned about protocol. I learned later that whereas DEC allocated rank and salary fairly strictly to the actual job being performed by the individual, Ciba-Geigy had a system of managerial ranks based on length of service, overall performance, and the personal background of the individual rather than on the actual job being performed at a given time. Rank and status therefore had a much more permanent quality in Ciba-Geigy, whereas in DEC, fortunes could rise and fall precipitously and frequently with job assignment.

In Ciba – Geigy meetings, I observed much less direct confrontation and much more respect for individual opinion. Meetings were geared to information transmission rather than problem solving. Recommendations made by managers in their specific area of accountability were generally respected, accepted, and implemented. I never observed insubordination, and I got the impression that it would not be tolerated. Rank and status thus clearly had a higher value in Ciba-Geigy than in DEC, whereas personal negotiating skill and the ability to get things done in an ambiguous social environment had a higher value in DEC.

2. Espoused Beliefs and Values

Beliefs and values tend to be elicited when you ask about observed behavior or other artifacts that strike you as puzzling, anomalous, or inconsistent. If I asked managers in Ciba-Geigy why they always kept their doors closed, they would patiently and somewhat condescendingly explain to me that this was the only way they could get any work done, and they valued work very highly. Meetings were a necessary evil and were useful only for announcing decisions or gathering information. “Real work” was done by thinking things out and that required quiet and concentration. In contrast, in DEC, real work was accomplished by debating things out in meetings!

It was also pointed out to me that discussion among peers was not of great value and that important information would come from the boss. Authority was highly respected, especially authority based on level of education, experience, and rank. The use of titles such as doctor or professor symbolized their respect for the knowledge that education bestowed on people. Much of this had to do with a great respect for the science of chemistry and the contributions of laboratory research to product development.

In Ciba-Geigy, as in DEC, a high value was placed on individual effort and contribution, but in Ciba-Geigy, no one ever went outside the chain of command and did things that would be out of line with what the boss had suggested. In Ciba-Geigy, a high value was placed on product elegance and quality, and, as I discovered later, what might be called product significance. Ciba-Geigy managers felt very proud of the fact that their chemicals and drugs were useful in crop protection, in curing diseases, and in other ways helping to improve the world.

3. Basic Assumptions-The Ciba-Geigy Company Paradigm

Many of the values that were articulated gave a flavor of this company, but without digging deeper to basic assumptions, I could not fully understand how things worked. For example, the artifact that struck me most as I worked with this organization on the mandate to help them to become more innovative was the anomalous behavior around my memos, previously mentioned in Chapter One. I realized that there was very little lateral communication occurring between units of the organization, so that new ideas developed in one unit never seemed to get outside that unit. If I inquired about cross-divisional meetings, for example, I would get blank stares and questions such as “Why would we do that?” Because the divisions were facing similar problems, it would obviously have been helpful to circulate some of the better ideas that came up in my interviews, supplemented with my own ideas based on my knowledge of what went on in other organizations.

Elaborating on the example provided in Chapter One, I wrote a number of memos along these lines and asked my contact client, Dr. Leupold, the director of management development, to distribute them to those managers he thought could most benefit from the information. Because he reported directly to Sam Koechlin, he seemed like a natural conduit for communicating with those divisional, functional, and geographic managers who needed the information I was gathering. When I would return on a subsequent visit to the company and meet with one of the unit managers, without fail I would discover that he did not have the memo, but if he requested it from Dr. Leupold, it would be sent over almost immediately.

This phenomenon was puzzling and irritating, but its consistency clearly indicated that some strong underlying assumptions were at work here. When I later asked one of my colleagues in the corporate staff unit that delivered training and other development programs to the organization why the information did not circulate freely, he revealed that he had similar problems in that he would develop a helpful intervention in one unit of the organization, but that other units would seek help outside the organization before they would “discover” that he had a solution that was better. The common denominator seemed to be that unsolicited ideas were generally not well received.

We had a long exploratory conversation about this observed behavior and jointly figured out what the explanation was. As previously mentioned, at Ciba-Geigy, when a manager was given a job, that job became the private domain of the individual. Managers felt a strong sense of turf or ownership and made the assumption that each owner of a piece of the organization would be completely in charge and on top of his piece. He would be fully informed and make himself an expert in that area. Therefore, if someone provided some unsolicited information pertaining to the job, this was potentially an invasion of privacy and possibly an insult, as it implied that the manager did not already have this information or idea.

The powerful metaphor that “giving someone unsolicited information was like walking into their home uninvited” came from a number of managers in subsequent interviews. It became clear that only if information was asked for was it acceptable to offer ideas. Someone’s superior could provide information, though even that was done only cautiously, but a peer would rarely do so, lest he unwittingly insult the recipient. To provide unsolicited information or ideas could be seen as a challenge to the information base the manager was using, and that might be regarded as an insult, implying that the person challenged had not thought deeply enough about his own problem or was not really on top of his own job.

By not understanding this assumption, I had unwittingly put Dr. Leupold into the impossible position of risking insulting all his colleagues and peers if he circulated my memos as I had asked. Interestingly enough, this kind of assumption is so tacit that even he could not articulate just why he had not followed my instructions. He was clearly uncomfortable and embarrassed about it but had no explanation until we uncovered the assumption about organizational turf and its symbolic meaning.

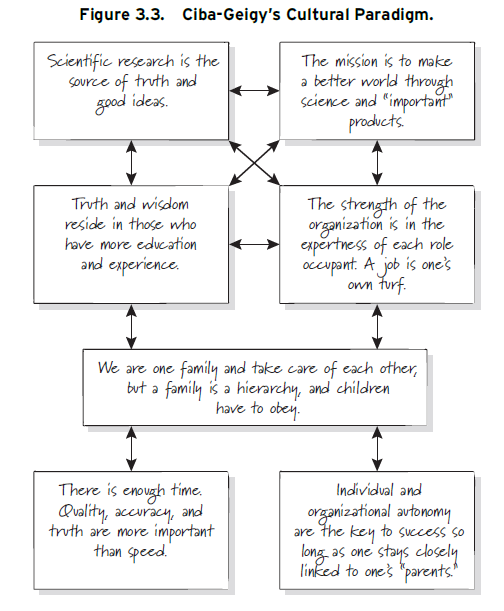

To further understand this and related behavior, it was necessary to consider some of the other underlying assumptions that this company had evolved (see Figure 3.3). It had grown and achieved much of its success through fundamental discoveries made by a number of basic researchers in the company ’s central research laboratories. Whereas in DEC truth was discovered through conflict and debate, in Ciba -Geigy truth had come more from the wisdom of the scientist/researcher.

Both companies believed in the individual, but the differing assumptions about the nature of truth led to completely different attitudes toward authority and the role of conflict. In Ciba-Geigy, authority was much more respected, and conflict tended to be avoided. The individual was given areas of freedom by the boss and then was totally respected in those areas. If role occupants were not well enough educated or skilled enough to make decisions, they were expected to train themselves. If they performed poorly in the meantime, that would be tolerated for quite a while before a decision might be made to replace them. In both companies, there was a “tenure” assumption that once people were accepted, they were likely to remain unless they failed in a major way.

In DEC, conflict was valued and the individual was expected to take initiative and fight for ideas in every arena. In Ciba-Geigy, conflict was suppressed once a decision had been made. In DEC, it was assumed that if a job was not challenging or was not a good match between what the organization needed and what the individual could give, the individual should be moved to a new assignment or would quit anyway. In Ciba-Geigy, the person would be expected to be a good soldier and do the job as best he could, and as long as he was perceived as doing his best he would be kept in the job.

Both companies talked of being families, but the meaning of the word family was quite different in each company. In DEC, the essential assumption was that family members could fight, but they loved each other and could not lose membership. In Ciba-Geigy, the assumption was that parental authority should be respected and that children (employees and subordinate managers) should behave according to the rules and obey their parents. If they did so, they would be well treated, taken care of, and supported by the parents. In DEC, lifetime employment was implicit, while in Ciba-Geigy, it was taken for granted and informally affirmed. In each case, the family model also reflected the wider macrocultural assumptions of the countries in which these companies were located.

After I understood the Ciba-Geigy paradigm, I was able to figure out how to operate more effectively as a consultant. As I interviewed more managers and gathered information that would be relevant to what they were trying to do, instead of attempting to circulate memos to the various branches of the Ciba-Geigy organization through my contact client, I found that if I gave information directly, even if it was unsolicited, it was accepted because I was an “expert.” If I wanted information to circulate, I sent it out to the relevant parties on my own initiative, or, if I thought it needed to circulate down into the organization, I gave it to the boss and attempted to convince him that the information would be relevant lower down. If I really wanted to intervene by having managers do something different, I could accomplish this best by being an expert and formally recommending it to CEO Sam Koechlin. If he liked the idea, he would then order “the troops” to do it. For example, I had given some lectures on “career anchors” illustrating that different people in the organization built their career around different core values, and that jobs should be described not in terms of responsibilities but in terms of their role networks. Koechlin mandated that the top several layers of the organization should do the career anchor exercise and analyze their role networks (Schein, 1978, 2006).

Other facets of the Ciba-Geigy culture will be discussed in later chapters. For example, their patience and their attitude toward time, and their formality along with their ability to be playful and informal during organizational “time outs” are important in understanding how they were able to get their work done.

Source: Schein Edgar H. (2010), Organizational Culture and Leadership, Jossey-Bass; 4th edition.

Perfect work you have done, this site is really cool with good info .