Earlier in this chapter we referred several times to problems caused by the way projects are organized and fit in as a part of the parent organization. It is now time to deal with this subject. Project organization is also discussed in Chapter 2: Organizational Influences and Project Life Cycle of PMBOK. It would be most unusual for a PM to have any influence over the way work is structured in the parent organization and how projects are fit within this structure. Rather, the organizational structure is decided by senior management. The way the organization is structured, however, has a major impact on the PM’s life, and it is necessary that the PM understand the implications of fitting projects into alternative organizational structures.

1. Pure Project Organization

Consider the construction of a football stadium or a shopping mall. Assume that the land has been acquired and the design approved. Having won a competitive bid, a contractor assigns a project manager and a team of construction specialists to the project. Each specialist, working from the architectural drawings, develops a set of plans to deal with his or her particular specialty area. One may design and plan the electrical systems, another the mechanicals, still another the parking and landscaping, and so forth. In the meantime, someone is arranging for the timely delivery of cranes, earth movers, excavation equipment, lumber, cement, brick, and other materials. And someone is hiring a suitable number of local construction workers with the appropriate skills. See Figure 2-5 for a typical pure project organization.

The supplies, equipment, and workers arrive just when they are needed (in a perfect world), do the work, complete the project, and disband. The PM is, in effect, the CEO of the project. When the project is completed, accepted by the client, equipment returned, and local workers paid off, then the PM and the specialists return to their parent firm and await the next project.

For organizations like our construction example here, the work of the organization is of a finite nature and therefore is naturally organized into projects. Other examples include law firms assigning lawyers to specific trials, consulting firms assigning teams to client engagements, studios assigning personnel to specific movie projects, and marketing research firms that assign analysts to specific client projects. In each of these cases, the work performed by the organization is of a fixed duration, making it logical and natural to organize the work and resources around specific projects. In these situations, when the work is completed on one project, the resources are shifted to another project. For example, as one trial wraps up, the attorneys in a law firm can be assigned to another trial. When work is structured and organized on the basis of projects, it is referred to as a pure project organization.

One challenge pure project organizations face is planning the smooth transition of resources from one project to another. For example, in a law firm a particular attorney may be needed on another trial before the one she/he is working on is completed. Alternatively, a trial may finish up before the attorney is needed for the next trial. There are other drawbacks to the pure project. While they have a broad range of specialists, they have limited technological depth. If the project’s resident specialist in a given area of knowledge happens to be lacking in a specific subset of that area, the project must hire a consultant, add another specialist, or do without. If the parent organization has several concurrent projects drawing on the same specialty areas, they develop fairly high levels of duplication in these specialties. This is expensive.

There are other problems, and one of the most serious is seen in R&D projects or in projects that have fairly long lives. People assigned to the project tend to form strong attachments to it. The project begins to take on a life of its own. A disease we call “pro- jectitis” develops. One pronounced symptom is worry about “Is there life after the project?” Foot dragging as the project end draws near is common, as is the submission of proposals for follow-up projects in the same area of interest—and, of course, using the same project team.

Nevertheless, despite these challenges and drawbacks, the pure project organization is well suited to situations where the nature of the work is of a finite nature. In particular, the pure project organization provides the requisite flexibility to effectively mobilize the organization’s resources to complete work that by its nature is of a finite duration.

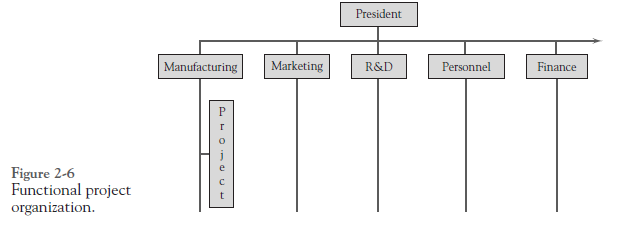

2. Functional Project Organization

Some projects have a very different type of structure. Assume, for example, that a project is formed to install a new automated production machine in an operating production line. The project includes the removal of the old machine and the integration of the new machine into the production system. In such a case, we would probably house the project in the Manufacturing division where the production system is located. Figure 2-6 shows a typical example of functional project organization with the project in this case, housed in the manufacturing function.

Based on Adam Smith’s division of labor concept, it is still common today to see organizations that have structured work activities around the type or function of the work. Thus, we see marketing, accounting, manufacturing, engineering, and other departments in many organizations. Likewise, in universities we see the faculty separated into different schools based on their discipline such as liberal arts, business, engineering, law, and medicine. It is also common to find projects housed within a particular functional department. Examples include a marketing department conducting a marketing research project, an engineering department working on a new product development project, and a business school developing the curriculum for a new master’s program in Business Analytics.

In contrast to pure project organizations where the work is organized around specific projects, functionally organized projects are embedded in the functional group where the project will be used. This immediately addresses some of the challenges associated with pure projects. First, the functional project has immediate, direct, and complete contact with the most important technologies it may need, and it has in-depth access. Second, project it is will be minimal because the project is not removed from the parent organization and specialists are not divorced from their normal career tracks.

A key challenge associated with functionally organized projects is communication across functional departments. Communications across functional department boundaries are rarely as simple as most firms think they are. When technological assistance is needed from another department, it may or may not be forthcoming on a timely basis. Technological depth is certainly present, but technological breadth is missing. The same problem exists with communication outside the function. In the pure project, communication lines are short and messages move rapidly. This is particularly important when the client is sending or receiving messages. In most functionally organized projects, the lines of communication to people or units outside the functional department are slow and tortuous. Traditionally, messages are not to be sent outside the division without clearing through the department’s senior management. Insisting that project communications follow the organizational chain of command imposes impossible delays on most projects. It most certainly impedes frank and open communication between project team members and the project client.

On the other hand, a key benefit of the functional project is that the priority assigned to the project is determined by the department that is also the client of the project. Because the project is housed in the department that will benefit from the project, the department’s leadership team has more leeway in determining the priority of the project relative to other departmental work and is subjected less to the concerns and priorities of other departments. Of course, this could also lead to suboptimization where the achievement of one department’s goals comes at the detriment of the overall organization.

3. Matrix Project Organization

In an attempt to capture the advantages of both the pure project organization and the functionally organized project as well as to avoid the problems associated with each type, a new type of project organization—more accurately, a combination of the two—was developed.

To form a matrix organized project, a pure project is superimposed on a functionally organized system as in Figure 2-7. The PM reports to a program manager or a vicepresident of projects or some senior individual with a similar title whose job it is to coordinate the activities of several or all of the projects. These projects may or may not be related, but they all demand the parent’s resources and the use of resources must be coordinated, if not the projects themselves. This method of organizing the interface between projects and the parent organization succeeds in capturing the major advantages of both pure and functional projects. It does, however, create some problems that are unique to this matrix form. To understand both the advantages and disadvantages, we will examine matrix management more closely.

As the figure illustrates, there are two distinct levels of responsibility in a matrix organization. First, there is the normal functional hierarchy that runs vertically in the figure and consists of the regular departments such as marketing, finance, manufacturing, human resources, and so on. (We could have illustrated a bank or university or an enterprise organized on some other principle. The departmental names would differ, but the structure of the system would be the same.) Second, there are horizontal structures, the projects that overlay the functional departments and, presumably, have some access to the functional department’s competencies. Heading up these horizontal projects are the project managers.

A close examination of Figure 2-7 shows some interesting details. Project 1 has assigned to it three people from the Manufacturing division, one and one-half from Marketing, a half-time person from Finance, four from R&D, and one-half from Personnel, plus an unknown number from other divisions not shown in the figure. Other projects have different make-ups of people assigned. This is typical of projects that have different objectives. Project 2, for example, appears to be aimed at the development of a new product with its concentration of Marketing representation, plus significant assistance from R&D, representation from Manufacturing, and staff assistance from Finance and Personnel. The PM controls what these people do and when they do it. The head of a functional group controls who from the group is assigned to the project and what technology is appropriate for use on the project.

Advantages We can disregard the problems raised by the split authority for the moment and concentrate on the strong points of this arrangement. Because there are many possible combinations of the pure project and the functional project, the matrix project may have some characteristics of each organizational type. If the matrix project closely resembles the pure project with many individuals assigned full-time to the project, it is referred to as a “strong” matrix or a “project” matrix. If, on the other hand, functional departments assign resource capacity to the project rather than people, the matrix is referred to as a “weak” matrix or a “functional” matrix. The project might, of course, have some people and some capacity assigned to it, in which case it is sometimes referred to as a “balanced” matrix. (The Random House Unabridged Dictionary defines “balanced” as “being in harmonious or proper arrangement. . . .” In no way does the balanced matrix qualify as “balanced.”) None of the terms—strong, weak, balanced—is precise, and matrix projects may be anywhere along the continuum from strong to weak. It may even be stronger or weaker at various times during the project’s life.

The primary reason for choosing a strong or weak matrix depends on the needs of both the project and the various functional groups. If the project is likely to require complex technical problem solving, it will probably have the appropriate technical specialists assigned to it. If the project’s technology is less demanding, it will be a weaker matrix that is able to draw on a functional group’s capacity when needed. A firm manufacturing household oven cleaners might borrow chemists from the R&D department to develop cleaning compounds that could dissolve baked-on grease. The project might also test whether such products were toxic to humans by using the capacity of the firm’s Toxicity Laboratory rather than having individual toxicity testers assigned to the project team.

One of the most important strengths of the matrix form is this flexibility in the way it can interface with the parent organization. Because it is, or can be, connected to any or all of the parent organization’s functional units, it has access to any or all of the parent organization’s technology. The way it utilizes the services of the several technical units need not be the same for each unit. This allows the functional departments to optimize their contributions to any project. They can meet a project’s needs in a way that is most efficient. Being able to share expertise with several projects during a limited time period makes the matrix arrangement far less expensive than the pure project with its duplication of competencies, and just as technologically “deep” as the functional project. The flexibility of the matrix is particularly useful for globalized projects that often require integrating knowledge and personnel coming from geographically dispersed independent business units, each of which may be organized quite differently than the others.

The matrix has a strong focus on the project itself, just as does the pure project. In this, it is clearly superior to the functional project that often is subordinate to the regular work of the functional group. In general, matrix organized projects have the advantages of both pure and functional projects. For the most part, they avoid the major disadvantages of each. Close contact with functional groups tends to mitigate projectitis. Individuals involved with matrix projects are never far from their home department and do not develop the detached feelings that sometimes strike those involved with pure projects.

Disadvantages With all their advantages, matrix projects have their own, unique problems. By far the most significant of these is the violation of an old dictum of the military and of management theory, the Unity of Command principle: For each subordinate, there shall be one, and only one, superior. In matrix projects, the individual specialist borrowed from a function has two bosses. As we noted above, the project manager may control which tasks the specialist undertakes, but the specialist reports to a functional manager who makes decisions about the specialist’s performance evaluation, promotion, and salary. Thus, project workers are often faced with conflicting orders from the PM and the functional manager. The result is conflicting demands on their time and activities. The project manager is in charge of the project, but the functional manager is usually superior to the PM on the firm’s organizational chart, and may have far more political clout in the parent organization. Life on a matrix project is rarely comfortable for anyone, PM or worker.

As we have said, in matrix organizations the PM controls administrative decisions and the functional heads control technological decisions. This distinction is simple enough when writing about project management, but for the operating PM the distinction, and partial division of authority and responsibility, is complex indeed. The ability of the PM to negotiate anything from resources to technical assistance to delivery dates is a key contributor to project success. As we have said before and will certainly say again, success is doubtful for a PM without strong negotiating skills.

While the ability to balance resources, schedules, and deliverables between several projects is an advantage of matrix organization, that ability has its dark side. The organization’s full set of projects must be carefully monitored by the program manager, a tough job. Further, the movement of resources from project to project in order to satisfy the individual schedules of the multiple projects may foster political infighting among the several PMs. As usual, there are no winners in these battles. Naturally, each PM is more interested in ensuring success for his or her individual project than in maintaining general organizationwide goals. Not only is this suboptimization injurious to the parent organization, it also raises serious ethical issues. In Chapter 1 we discussed some of the issues involved in aggregate planning, and we will have much more to say on this matter in Chapter 6.

Intrateam conflict is a characteristic of all projects, but the conflicts seem to us to be particularly numerous and contentious in matrix projects. In addition to conflicts arising from the split authority and from the violation of Unity of Command, another major source of conflict appears to be inherent in the nature of the transdisciplinary teams in a matrix setting. Functional projects have such teams, but team members have a strong common interest, their common functional home. Pure projects have transdisciplinary teams, but the entire team is full-time and committed to the project. Matrix project teams are transdisciplinary, but team members are often not full-time, have different functional homes, and have other commitments than the project. They are often committed to their functional area or to their career specialty, rather than to the project. As we emphasize in the next section, high levels of trust between project team members is critical for optimum team performance. Conflicts do not necessarily lead to distrust on a project team, but unless matrix organized teams are focused on the project rather than on their individual contribution to it, distrust between team members is almost certain to affect project outcomes negatively.

A young man of our acquaintance works one-quarter time on each of two projects and half-time in his functional group, the mechanical engineering group in an R&D division. He estimates that approximately three-quarters of the time he is expected to be in two or more places at the same time. He indicated that this is normal.

With all its problems, there is no real choice about project organization for most firms. Functional projects are too limited and too slow. Pure projects are far too expensive. Matrix projects are both effective and efficient. They are here to stay, conflict and all.

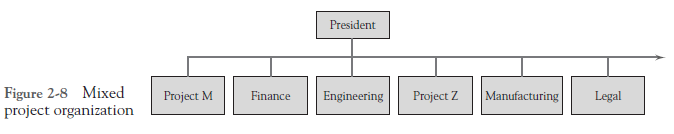

4. Mixed Organizational Systems

Functional, matrix, and pure projects exist side by side in some organizations (see Figure 2-8). In reality, they are never quite as neatly defined as they appear here. For example, a management consulting firm that mostly follows a pure project structure may also have a central Human Resources department that completes projects housed entirely within the department.

The ability to organize projects to fit the needs of the parent firm has allowed projects to be used under conditions that might be quite difficult were project organization constrained to one or two specific forms. As the hybridization increases, though, the firm risks increasing the level of conflict in and between projects because of duplication, overlapping authority, and increased friction between project and functional management.

5. The Project Management Office and Project Maturity

There is another way of addressing some of the challenges associated with the alternative organizational forms for projects. The parent organization can set up a project management office (PMO), more or less like a functional group or as a center of excellence with its own manager. This group may act as staff to some or to all projects (Block, 1998; Bolles, 1998). The project office may handle some or all of the budgeting, scheduling, reporting, scope, compliance with corporate governance, and risk management activities while the functional units supply the technical work. The PMO often serves as a repository for project documents and histories. However, the PMO must never replace the project manager as officer in charge of and accountable for the project.

At times the PMO is effective, and at times it is not. Based on limited observation, it appears to us that the system works well when the functional specialists have fairly routine projects. If this is not the case, the PMO might be involved in generating the project’s budget, schedule, and scope, and must be kept well informed about the progress of the project measured against its goals. Some years ago, a large pharmaceutical firm used a similar arrangement on R&D projects, the purpose being to “protect” their scientists from having to deal with project schedules, budgets, and progress reports, all of which were handled by the PMO. The scientists were not even bothered with having to read the reports. The result was precisely what one might expect. All projects were late and over budget—very late and far over budget.

But in another case, the U.S. Federal Transportation Security Administration had only 3 months and $20 million to build a 13,500 square foot coordination center, involving the coordination of up to 300 tradespeople working simultaneously on various aspects of the center (PMI, May 2004). A strong Project Management Office was crucial to making the effort a success. The PMO accelerated the procurement and approval process, cutting times in half in some cases. They engaged a team leader, a master scheduler, a master financial manager, a procurement specialist, a civil engineer, and other specialists to manage the multiple facets of the construction project, finishing the entire project in 97 days and on budget, receiving an award from the National Assn. of Industrial and Office Properties for the quality of its project management and overall facility.

In general, however, the role of the PMO is much broader than this example, and it is now not uncommon to find several different types of PMOs existing at different levels of large firms with different, but sometimes overlapping, areas of operation. They have titles such as CPMO for Corporate Project Management Office, or EPMO for Enterprise Project Management Office, and many other variants. It is also common to find an EPMO (or CPMO) followed by a PMO for each unit of the parent organization that actually carries out the projects and reports to the senior EPMO.

Involvement of senior management in EPMOs allows the EPMO to provide some important functions. The EPMO (or PMO if there is only one in the firm) is in a unique position to oversee the practices of the firm’s portfolio of projects, checking the consistency of the projects with the firm’s strategies, generating and insuring compliance with matters of corporate governance, maintaining project histories as well as composite data on project costs, schedules, and so on, setting project or program priorities across departments, helping projects to acquire resources, and similar issues. Project sponsors, senior managers who have a strong interest in a project or program and may use their political clout to help the project with priority issues or resource acquisition when such clout may be useful, are often appropriate members of the EPMOs. Again, care must be taken for the EPMO or its individual members to avoid usurping the PM as the accountable, officer-in-charge of the project.

While such activities are necessary and, indeed, helpful, EPMO actions sometimes may cause significant management problems. Because many senior managers have little or no training in project management, they tend to focus on assessment of project progress and evaluation by using planned cost versus actual cost as a primary measurement tool. (We will discuss the problems caused by this simplistic measure several times in the following chapters, and in some detail in Chapter 7 on Project Control.) As senior management has become aware of these and other problems, many EPMOs have taken on the task of assuring that the organization is following “best practices” for the management of its projects. The EPMO is expected to monitor and continuously improve the organization’s project management skills. In the past few years, a number of different ways to measure this “project management maturity” (Pennypacker et al., 2003) have been suggested, such as basing the evaluation on PMI’s PMBOK Guide (Lubianiker, 2000; see also www.pmi.org) or the ISO 9001 standards of the International Organization for Standardization.

Quite a few consulting firms, as well as scholars, have devised formal maturity measures; one such, PM3, is described by R. Remy (1997). In this system, the final project management “maturity” of an organization is assessed as being at one of five levels: ad-hoc (disorganized, accidental successes and failures); abbreviated (some processes exist, inconsistent management, unpredictable results); organized (standardized processes, more predictable results); managed (controlled and measured processes, results more in line with plans); and adaptive (continuous improvement in processes, success is normal, performance keeps improving).

Another maturity model was applied to 38 organizations in four industries (Ibbs and Kwak, 2000). The survey included 148 questions covering six processes/life cycle phases (initiating, planning, executing, controlling, closing, and project-driven organization environment) and ten PMBOK knowledge areas (integration, scope, time, cost, quality, human resources, communication, risk, procurement, and stakeholders). The model assesses project management maturity in terms of five stages called: ad hoc, planned, managed, integrated, and sustained.

Regardless of the model form, it appears that most organizations do not score very well in maturity tests. On one form, about three-quarters are no higher than level 2 (planned) and fewer than 6 percent are above level 3. Individual firms ranged from 1.8 to 4.6 on the five-point scale.

Source: Meredith Jack R., Mantel Jr. Samuel J., Shafer Scott M., Sutton Margaret M. (2017), Project Management in Practice, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 3th Edition.

I believe you have mentioned some very interesting details , thankyou for the post.