We have mentioned the project team several times in the foregoing sections. Effective team members have some characteristics in common. Only the first of these is usually taken into account.

- They must be technically competent. This is so obvious that it is often the only criterion applied. While the functional departments will always remain the ultimate source of technological problem solving for the project, it requires a technically competent person to know exactly when additional technical knowledge may be required by the project.

- Senior members of the project team must be politically sensitive. It is rarely possible to complete a project of reasonable size and complexity without incurring problems that require aid from the upper echelons of executive row; that is, from a project sponsor (Pinto and Slevin, 1989). Getting such aid depends on the PM’s ability to proceed without threatening, insulting, or bullying important people in the functional groups. To ensure cooperation and assistance, there is a delicate balance of power that must be maintained between the project and the functional departments, and between one project and others.

- Members of the project team need a strong problem orientation. This characteristic will be explained in more detail shortly. For now, take the phrase to mean that the team’s members should be concerned about solving any problems posed by the project, not merely about those subproblems that concern their individual academic or technical training.

- Team members need a strong goal orientation. Projects are uncomfortable environments for people with a 9-to-5 view of work. In particular, neither project teams nor PMs can succeed if their focus is on activity rather than results. On the other hand, the project will not be successful if the project team dies from overwork. One project team member of our acquaintance was bemoaning a series of 60+ hour weeks. “They told me that I would work about 50 hours in an average week. I’ve been on this project almost 18 months, and we haven’t had an average week yet.”

- Project workers need high self-esteem. Project members who hide mistakes and failure are disasters waiting to happen. Team members must be sufficiently selfconfident and have sufficient trust in their fellow team members (Lencioni, 2002) that they can immediately acknowledge their own errors and point out problems caused by the errors of others. PMs should note that “shooting the messenger” who brings bad news will instantly stop the flow of negative information. The result is that the golden rule we stated above, “Never let the boss be surprised,” will be violated, too.

Gathering such a team is a nontrivial job. If it is done well, motivation of team members is rarely a problem. Remember that the functional managers control the pay and promotion of project workers in a matrix system. Fortunately, it has been shown that a sense of achievement, growth, learning, responsibility, and the work itself are strong motivators, and the project is a high-visibility source of these.

In a large project, the PM will have a number of “assistant managers” on the project team—a senior engineer, field manager, contract administrator, support services manager, and several other individuals who can help the PM determine the project’s needs for staff and resources. (In the next chapter we will see precisely how the staff and resource requirements are determined.) They can also help to manage the project’s schedule, budget, and technical performance. For a large project, such assistance is necessary. For a small project the PM will probably play all these roles.

As a final thought, the PM should expect conflict with the creation of a new project team where the individual team members do not know one another. To help navigate the conflict, it is helpful if the PM understands the way teams tend to develop. One of the more popular classic models of team development is one referred to as the “Tuckman ladder” (Tuckman, 1965), which suggests that teams progress through the following four development phases:

- Forming. Team members come together for the first time and begin learning about their roles and responsibilities.

- Storming. Work on the project begins, but initially the team members tend to work independently, which often leads to conflict.

- Norming. In this phase, the team members begin to establish team norms and team cohesiveness develops. Individual team members reconcile their behaviors to support the overall team and trust develops.

- Performing. With norms and trust established, teams function as a cohesive unit focused on accomplishing the goals of the project.

In addition to these four phases, a fifth phase, “adjourning,” has also been proposed. In the adjourning phase, the work of the project is completed and the team members return to their functional departments or move on to another project. While teams tend to progress through these phases in the order listed above, it is also important to point out that they can get stuck in one or more of the phases, backtrack to an earlier phase, or never make it to the later phases. Likewise, if the team members have worked together previously, it is possible that one or more phases may be skipped.

1. Matrix Team Problems

The smaller the project, the more likely it is to be organized as a weak (functional) matrix. In such projects the PM may have no direct reports. The PM contracts with functional managers for capacity, but often knows most of the individuals who are doing the actual work. Thus, the PM can usually communicate directly with project workers, even in the weakest of matrices. In the case of small projects, this ability to communicate directly with members of the project team (even though they are not officially a team at all) is important. It is the only way the PM can keep the project a coordinated effort and on course. Again, the ability to communicate with and direct functional specialists working on project tasks is dependent on the PM’s ability to negotiate with the functional manager. Actually, the negotiation is not too difficult because the PM is tacitly taking responsibility to direct the workers’ performance. If the PM is getting good performance from the functional specialists, this relieves the functional manager of some responsibility and accountability.

For matrix projects, it is particularly important to maintain good morale for the few project workers that may be assigned to the team. A project “war room” is helpful, serving as a control center, conference room for project meetings, a coffee shop, technical discussion center, and crisis center. Earlier in this chapter, we noted the use of a project staff office with a purpose of supplying the project with administrative assistance. The war room may also provide such a purpose, but its ability to serve as a focal point for project team activity and heighten the project’s esprit de corps makes a significant contribution to matrix projects. The Walt Disney Co. sets up division-wide project war rooms and expects the PMs, the functional managers, and the division executive team to use the war room to stay abreast of project timelines and to identify areas of organizational impact on the project or vice versa.

A number of factors make matrix project teams unusually difficult to manage. Such teams are seen by their members to be temporary, so the tendency to develop team loyalty is limited. The technical specialists working on the teams are often perfectionists and have a strong desire to keep tinkering with a project deliverable that already meets the client’s specifications and expectations. While project managers usually blame the client for scope creep, it is not uncommon for the project team to be the primary cause. The principal source of management problems for the PM, however, is the level of conflict in project teams.

2. Intrateam Conflict

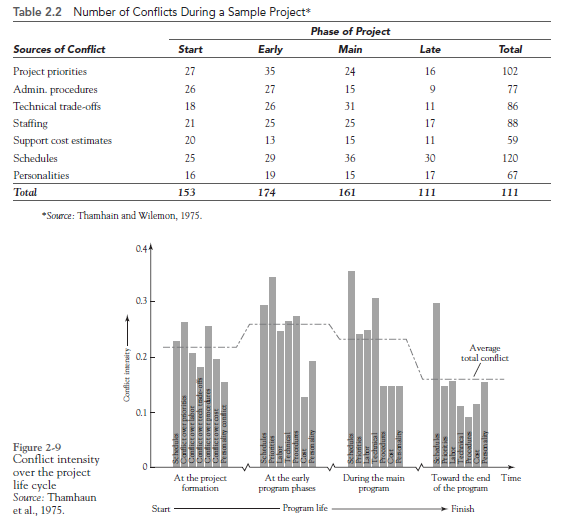

Conflict is no stranger to any workplace, but matrix projects seem to have far more than their share. The causes are many, but more than three decades ago Thamhain and Wilemon (1975) published their outstanding research on conflict in projects and this work remains absolutely relevant today. They identified several different sources of conflict and noted that the sources seemed to differ when the project was in different stages of its life cycle. They also made some recommendations for dealing with the conflicts. These are shown in Table 2-1. Table 2-2 shows the relative frequency of the various sources of conflict, and Figure 2-9 illustrates them.

A reading of the recommendations Thamhain and Wilemon made for reducing or preventing these conflicts reveals four common threads: (1) many of the recommendations feature careful project planning; (2) many are based on the practice of participative management; (3) many require interaction and negotiation between the PM and the functional departments; and (4) there is great emphasis on communication between the PM and all parties-at-interest to the project. Our next chapter is devoted to careful project planning, and we have already discussed the need for negotiation and communication. Participative management is a requirement for proper project planning, and it will be covered in the project-planning chapter. We will continue to mention, if not belabor, these four themes throughout the rest of this book.

Certain aspects of the data in Table 2-2 seem significant. Schedules are a major source of conflict throughout the project’s life. Priorities are a close second, particularly in the first two stages of the project’s life. Because the distinction between the project’s

“start” and the “early” phase of its life is probably unclear, we can lump them together for the observation that a lion’s share of the conflicts will come near the beginning of the project—and the PM must be prepared to deal with them.

One should not get the idea that conflict in the project team is all bad. Intrateam conflict often enhances team creativity. Out of arguments about competing good ideas come better ideas. For this to happen, however, parties to the conflict must be more interested in solving the problems at hand than they are about winning a victory for “their side.” As we have already noted, some people are discipline oriented and others are problem oriented. Discipline-oriented individuals form what one writer calls a “NOT” (Name-Only Team), which he defines as a group of individuals working independently (Dewhurst, 1998). The intrateam conflict caused by such people is usually perceived to be “interpersonal” or “political.” If such conflicts are the major force in project decisions, the project is apt to have problems. We strongly recommend Lencioni’s The Five Dysfunctions of a Team (2002) to the reader’s attention and we again emphasize our earlier advice to the PM to recruit problem-oriented team members whenever possible.

A great deal has been written about conflict resolution as well as about negotiation (see Afzalur, 1992, for example). Those two literatures have much in common. Both make it clear that the key to resolving conflict lies in the mediator’s ability to transform win-lose situations into win-win solutions. This is also true when the mediator (usually the PM) is one of the parties to the conflict. One of the most important things a PM can do is develop sensitivity for conflict and then intervene early, before the conflict has hardened into hostility. Conflict avoidance, while it may appear to provide short-term comfort, is never a useful course of action for the PM.

Interpersonal conflict, unfortunately, never stays interpersonal. It impacts on the relationships between various groups and spills over to affect the ways in which these groups cooperate or fail to cooperate with each other. This, in turn, affects the ability of the PM to keep the project on course. The most difficult aspect of managing a project is the coordination and integration of its various elements so that they meet their joint goals of performance, schedule, and budget in such a way that the total project meets its goals.

When the project is complex, involving input and work from several departments or groups and possibly other contributions from several outside contractors, the intricate process of coordinating the work and timing of these inputs is difficult. When the groups are in conflict, the process is almost impossible. The task of bringing the work of all these groups together to make a harmonious whole is called integration management.

3. Integration Management

The problems of integration management are easily understood if we consider the traditional way in which products and services were designed and brought to market. The different groups involved in a product design project, for example, did not work together. They worked independently and sequentially. First, the product design group developed a design that seemed to meet the marketing group’s specifications. This design was submitted to top management for approval, and possible redesign if needed. When the design was accepted, a prototype was constructed. The project was then transferred to the engineering group who tested the prototype product for quality, reliability, manufacturability, and possibly altered the design to use less-expensive materials. There were certain to be changes, and all changes were submitted for management approval, at which time a new prototype was constructed and subjected to testing.

After qualifying on all tests, the project moved to the manufacturing group who proceeded to plan the actual steps required to manufacture the product in the most cost-effective way, given the machinery and equipment currently available. Again, changes were submitted for approval, often to speed up or improve the production process. If the project proceeded to the production stage, distribution channels had to be arranged, packaging designed and produced, marketing strategies developed, advertising campaigns developed, and the product shipped to the distribution centers for sale and delivery.

Conflicts between the various functional groups were legendary. Each group tried to optimize its contribution, which led to suboptimization for the system. This process worked reasonably well, if haltingly, in the past, but was extremely time consuming and expensive—conditions not tolerable in today’s competitive environment.

To solve these problems, the entire project was changed from one that proceeded sequentially through each of the steps from design to sale, to one where the steps were carried out concurrently. Parallel tasking (a.k.a. fast tracking) was invented as a response to the time and cost associated with the traditional “waterfall” method. Parallel tasking has been widely used for a great diversity of projects. For example, parallel tasking was used in the design and marketing of services by a social agency; to design, manufacture, and distribute ladies’ sportswear; to design, plan, and carry out a campaign for political office; to plan the maintenance schedule for a public utility; and to design and construct the space shuttle. Parallel tasking has been generally adopted as the proper way to tackle problems that are multidisciplinary in nature.

Monte Peterson, CEO of Thermos (now a subsidiary of Nippon Sanso, Inc.), formed a flexible interdisciplinary team with representatives from marketing, manufacturing, engineering, and finance to develop a new grill that would stand out in the market. The interdisciplinary approach was used primarily to reduce the time required to complete the project. For example, by including the manufacturing people in the design process from the beginning, the team avoided some costly mistakes later on. Initially, for instance, the designers opted for tapered legs on the grill. However, after manufacturing explained at an early meeting that tapered legs would have to be custom made, the design engineers changed the design to straight legs. Under the previous system, manufacturing would not have known about the problem with the tapered legs until the design was completed. The output of this project was a revolutionary electric grill that used a new technology to give food a barbecued taste. The grill won four design awards in its first year.

If the team members are problem oriented, parallel tasking works very well. Some interesting research has shown that when problem-oriented people with different backgrounds enter conflicts about how to deal with a problem, they often produce very creative solutions—and without damage to project quality, cost, or schedule. The group itself typically resolves the conflicts arising in such cases when they recognize that they have solved the problem. For some highly effective teams, conflict becomes a favored style of problem solving (Lencioni, 2002).

When team members are both argumentative and oriented to their own discipline, parallel tasking appears to be no improvement on any other method of problem solving. The PM will have to use negotiation, persuasion, and conflict resolution skills, but there is no guarantee that these will be successful. Even when intragroup conflict is not a serious issue with discipline-oriented team members, they often adopt suboptimization as the preferred approach to problem solving. They argue that experts should be allowed to exercise their specialties without interference from those who lack expertise. Successfully involving transfunctional teams in project planning requires that some structure be imposed on the planning process. The most common structure is simply to define the group’s responsibility as being the development of a plan to accomplish whatever is established as the project objective. There is considerable evidence, however, that this will not prevent conflict on complex projects.

Source: Meredith Jack R., Mantel Jr. Samuel J., Shafer Scott M., Sutton Margaret M. (2017), Project Management in Practice, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 3th Edition.

Good info. Lucky me I reach on your website by accident, I bookmarked it.