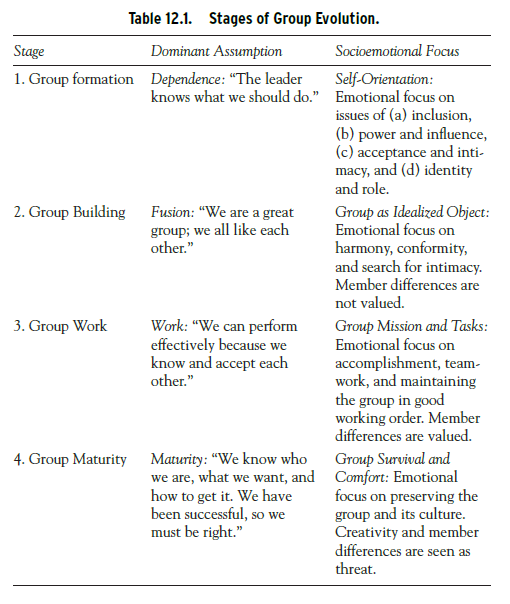

Initially, each member of a new group is struggling with the personal issues of inclusion, identity, authority, and intimacy, and the group is not really a group but a collection of individual members, each focused on how to make the situation safe and personally rewarding. Even as they learn how to learn in the T-group, they are much more preoccupied with their own feelings than with the problem of the group as a group and, most likely, they are operating on the unconscious assumption that “the leader [staff member] knows what we are supposed to do.” Therefore, the best way to achieve safety is to remain dependent on the staff member and try to find out what the group is supposed to do and do it. This group stage, with its associated feelings and moods, is, in my experience, similar to what Bion (1959) described in his work as the “dependence assumption” and what other theories note as the first issue the group has to deal with (Bennis & Shepard, 1956).

The evidence for the operation of this assumption is the behavior in the early minutes and hours of the group’s life. First of all, much of the initial behavior of group members is, in fact, directed to the staff member in the form of questions, requests for explanations and for suggestions about how to proceed, and constant checking for approval. Even if the behavior is not directed to the staff member, group members constantly look at him or her, pay extra attention if the staff member does speak, and in other nonverbal ways indicate their preoccupation with the staff member’s reaction.

Members may share the assumption of being dependent on the staff member yet react very differently. These differences can best be understood in terms of what they have learned in their prior macrocultural experience, starting in the family. One way to deal with authority is to suppress one ’s aggression, accept dependence, and seek guidance. If the staff member makes a suggestion, members who cope in this way will automatically accept it and attempt to do what is asked of them. Others have learned that the way to deal with authority is to resist it. They also will seek to find out what the leader wants, but their motive is to find out in order to resist rather than to comply—to be “counter dependent.” Still others will attempt to find other members to share their feelings of dependence and, in effect, set up a subgroup within the larger group.

The mixture of tendencies in the personalities of group members is, of course, not initially predictable, nor is any given person inflexible. The range of possible variations in response to the initial leadership/authority vacuum is thus immense in a ten- to fifteen-person group. The early interaction can best be described as a mutual testing out—testing of the staff member to see how much guidance will be offered, and testing by members of other members to see who can influence whom and who will control whom—a process not unlike establishing a pecking order in the barnyard.

Several members will emerge as competitors for leadership and influence. If any one of these members suggests something or makes a point, one of the others will contradict it or try to go off in a different direction. This aggressive competition among the “sturdy battlers” keeps the group from achieving any real consensus early in its life, and one paradox of group formation is that there is no way to short-circuit this early power struggle. If it is swept under the rug by strong authoritarian leadership or formal procedures, it will surface later around the task issues that the group is trying to address and will be potentially damaging to task performance. Interpersonal competition becomes one of many “covert processes” that the group will have to deal with (Marshak, 2006).

From the point of view of the staff member, confirmation that this process is indeed going on comes from the frequent experience of trying to give the group guidance and finding that some members leap at the help, while others almost blindly resist it. If frustration is high, one or the other extreme mode may build up in the group as a whole, what Bion labeled “fight or flight.” The group may collectively attack the staff member, aggressively deny his suggestions, and punish him for his or her silence, or the group may suddenly go off on its own, led by a group member, with the implicit or explicit statement “We need to get away from the disappointing leader and do it on our own.”

1. Building New Norms Around Authority

In its early life, the group cannot easily find consensus on what to do, so it bounces from one suggestion to another and becomes increasingly more frustrated and discouraged at its inability to act. And this frustration keeps the shared emotional assumption of dependency alive. The group continues to act as if the leader knows what to do. In the meantime, members are, of course, beginning to be able to calibrate each other, the staff member, and the total situation. As the group learns to analyze its own processes, a common language slowly gets established; and, as shared learning experiences accumulate, more of a sense of groupness arises at the emotional level, providing some reassurance to all that they are being included. Inclusion anxieties are slowly reduced.

This sense of groupness arises through successive dealings with marker events that arouse strong feelings and then are dealt with definitively. The group may not be consciously aware of this process of norm building, however, unless attention is drawn to it in process analysis periods. For example, within the first few minutes, a member may speak up strongly for a given course of action. Joe suggests that the way to proceed is to take turns introducing ourselves and stating why we are in the group. This suggestion requires some behavioral response from other members; therefore, no matter what the group does, it will be setting some kind of precedent for how to deal with future suggestions that are “controlling”—that require behavior from others.

What are the options at this point? One common response in groups is to act as if the suggestion had not even been made at all. There is a moment of silence, followed by another member’s comment irrelevant to the suggestion. This is the “plop”—a group decision by nonaction. The member who made the suggestion may feel ignored. At the same time, a group norm has been established. The group has, in effect, said that members need not respond to every suggestion, that it is permissible to ignore someone. A second common response is for another person to immediately agree or disagree overtly with the suggestion. This response begins to build a different norm—that a person should respond to suggestions in some way. If there has been agreement, the response may also begin to build an alliance; if there has been disagreement, it may begin a fight that will force others to take sides.

A third possibility is for another member to make a “process” comment, such as “I wonder if we should collect some other suggestions before we decide what to do?” or “How do the rest of you feel about Joe’s suggestion?” Again, a norm is being established—that a person does not have to plunge into action but can consider alternatives. A fourth possibility is to plunge ahead into action. The suggestion is made to introduce ourselves, and the next person to speak launches into an introduction. This response not only gets the group moving but may set two precedents: (1) that suggestions should be responded to, and (2) that Joe is the one who can get us moving. The implication of this last response is that Joe may feel empowered and be more likely to make a suggestion the next time the group is floundering. Note that this process happens very fast, often in a few seconds, so the important group consequences are not noticed until a process analysis period reconstructs them. As Joe becomes more of a leader, some group members may scratch their heads and wonder, how did Joe get anointed into this position. They don’t remember the early group events that de facto anointed him.

Norms are thus formed when an individual takes a position, and the rest of the group deals with that position by either letting it stand (by remaining silent), by actively approving it, by “processing” it, or by rejecting it. Three sets of consequences are always observed: (1) the personal consequences for the member who made the suggestion (he may gain or lose influence, disclose himself to others, develop a friend or enemy, and so on); (2) the interpersonal consequences for those members immediately involved in the interplay; and (3) the normative consequences for the group as a whole. So here again we have the situation in which an individual has to act, but the subsequent shared reaction turns the event into a group product. It is the joint witnessing of the event and the reaction that makes it a group product.

The early life of the group is filled with thousands of such events and the responses to them. At the cognitive level, they deal with the effort to define working procedures to fulfill the primary task—to learn. Prior assumptions about how to learn will operate initially to bias the group ’s effort, and limits will be set by the staff member in the form of calling attention to the consequences of behavior considered clearly detrimental to learning—behavior such as failure to attend meetings, frequent interruptions, personally hostile attacks, and the like. At the emotional level, such events deal with the problem of authority and influence. The most critical of such events are ones that overtly test or challenge the staff member’s authority. Thus, we note that the group pays special attention to the responses that occur immediately after someone has directed a comment, question, or challenge to the staff member.

We also note anomalous behavior that can be explained only if we assume that an authority issue is being worked out. For example, the group actively seeks leadership by requesting that some member should help the group to get moving, but then systematically ignores or punishes anyone who attempts to lead. We can understand this behavior if we remember that feelings toward authority are always ambivalent and that the anger felt toward the staff member for not leading the group cannot be expressed directly if the individual feels dependent on the staff member. The negative feelings are split off and projected onto a “bad leader,” thus preserving the illusion that the staff member is the “good leader.” Acts of insubordination or outbursts of anger at the staff member may be severely punished by other group members, even though those members have themselves been critical of the staff member.

How, then, does a group learn what is “reality”? How does it develop workable and accurate assumptions about how to deal with influence and authority? How does it normalize its relationship to the staff member, the formal authority who is presumed to know what to do and yet does not do it?

2. Reality Test and Catharsis

Though members begin to feel they know each other better, the group continues to be frustrated by its inability to act in a consensual manner because the unconscious dependence assumption is still operating, and members are still working out their influence relationships with each other. The event that moves the group forward at such times, often many hours into the group ’s life, is an insightful comment by a member who is less conflicted about the authority issue and, therefore, able to perceive and articulate what is really going on. In other words, while those members who are most conflicted about authority are struggling in the dependent and counterdependent mode, some members find that they care less about this issue, are able psychologically to detach themselves from it, and come to recognize the reality that for this particular group at this time in its history, the staff member does not and cannot, in fact, know what to do.

The less conflicted members may intervene in any of a number of ways that expose this reality: (1) by offering a direct interpretation—“Maybe we are hung up in this group because we expect the staff member to be able to tell us what to do, and he doesn’t know what to do”; (2) by offering a direct challenge—“I think the staff member doesn’t know what to do, so we better figure it out ourselves”; (3) by offering a direct suggestion for an alternative agenda—“I think we should focus on how we feel about this group right now, instead of trying to figure out what to do”; or (4) by making a process suggestion or observation—“I notice that we ask the leader for suggestions but then don’ t do what he suggests” or “I wonder why we are fighting so much among ourselves in this group” or “I think it is interesting that every time Joe makes a suggestion, Mary challenges him or makes a counter-suggestion.”

If the timing is right, in the sense that many members are “ready ” to hear what may be going on because they have all observed the process for a period of time, there will be a strong cathartic reaction when the assumption-lifting intervention is made. The group members will suddenly realize that they have been focusing heavily on the staff member and that, indeed, that person is not all-knowing and all-seeing and, therefore, probably does not, in fact, know what the group should do. With this insight comes the feeling of responsibility: “We are all in this together, and we each have to contribute to the group’s agenda.” The magical leader has been killed, and the group begins to seek realistic leadership from whoever can provide it.

Leadership comes to be seen as a shared set of activities rather than a single person’s trait, and a sense of ownership of group outcomes arises. Some work groups never achieve this state, remaining dependent on whatever formal authority is available and projecting magically onto it; but in the training/learning situation in the cultural island in which the social order is somewhat suspended, the emphasis on process analysis makes it very likely that the issue will be brought to the surface and dealt with.

A comparable process occurs in formally constituted groups, but it is less visible. The group founder or chairperson does have real intentions and plans, but the group initially tends to attribute far more complete and detailed knowledge to the leader than is warranted by reality. Thus, early in the life of a company, the entrepreneur is viewed much more magically as the source of all wisdom, and only gradually is it discovered that he or she is only human and that the organization can function only if other members begin to feel responsible for group outcomes as well. But all this may occur implicitly and without very visible marker events. If such events occur, they will most likely be in the form of challenges of the leader or outright insubordination. How the group and the leader then handle the emotionally threatening event determines, to a large extent, the norms around authority that will become operative in the future (as exemplified in the next chapter).

The “insight” that the leader is not omniscient or omnipotent gives members a sense of relief not to be struggling any longer with the staff members. They are likely to develop a feeling of euphoria that they have been able to deal with the tough issue of authority and leadership. There is a sense of joy in recognizing that everyone in the group has a role and can make a leadership contribution, and this, in turn, strengthens the group’s sense of itself.

At this point, the group often takes some joint action, as if to prove to itself that it can do something, and gets a further sense of euphoria from being successful at it. Such action is often externally directed—winning a competition with another group or tackling a difficult task under time pressure and completing it. Whatever the task, the end result is a feeling of “We are a great group” and possibly, at a deeper level, even the feeling of “We are a better group than any of the others.” It is this state of affairs that leads to the unconscious assumption of “fusion” and brings to the fore the intimacy issue.

Source: Schein Edgar H. (2010), Organizational Culture and Leadership, Jossey-Bass; 4th edition.

great post, i love it