The simplest explanation of how leaders get their message across is that they do it through “charisma”—that mysterious ability to capture the subordinates’ attention and to communicate major assumptions and values in a vivid and clear manner (Bennis and Nanus, 1985; Conger, 1989; Leavitt, 1986). Charisma is an important mechanism of culture creation, but it is not, from the organization’s or society’s point of view, a reliable mechanism of embedding or socialization because leaders who have it are rare, and their impact is hard to predict. Historians can look back and say that certain people had charisma or had a great vision. It is not always clear at the time, however, how they transmitted the vision. On

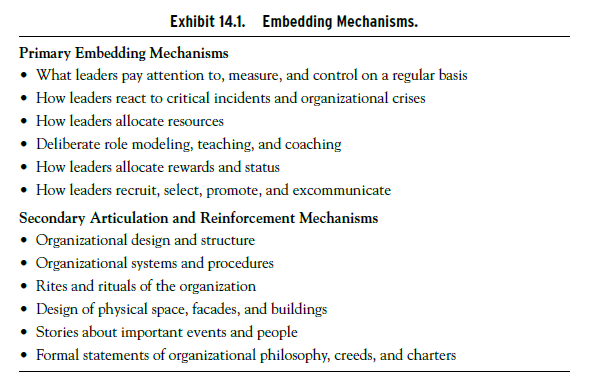

the other hand, leaders of organizations without charisma have many ways of getting their message across, and it is these other ways that will be the focus of this chapter. Exhibit 14.1 shows twelve embedding mechanisms divided into primary and secondary to highlight the difference between the most powerful daily behavioral things that leaders do and the more formal mechanisms that come to support and reinforce the primary messages.

1. Primary Embedding Mechanisms

The six primary embedding mechanisms shown in Exhibit 14.1 are the major “tools” that leaders have available to them to teach their organizations how to perceive, think, feel, and behave based on their own conscious and unconscious convictions. They are discussed in sequence, but they operate simultaneously. They are visible artifacts of the emerging culture that directly create what would typically be called the “climate” of the organization (Schneider, 1990; Ashkanasy, Wilderom, and Peterson, 2000).

What Leaders Pay Attention To, Measure, and Control. The most powerful mechanisms that founders, leaders, managers, and parents have available for communicating what they believe in or care about is what they systematically pay attention to. This can mean anything from what they notice and comment on to what they measure, control, reward, and in other ways deal with systematically. Even casual remarks and questions that are consistently geared to a certain area can be as potent as formal control mechanisms and measurements.

If leaders are aware of this process, then being systematic in paying attention to certain things becomes a powerful way of communicating a message, especially if leaders are totally consistent in their own behavior. On the other hand, if leaders are not aware of the power of this process, or they are inconsistent in what they pay attention to, subordinates and colleagues will spend inordinate time and energy trying to decipher what a leader ’s behavior really reflects and will even project motives onto the leader where none may exist. This mechanism is well captured by the phrase “you get what you settle for.”

It is the consistency that is important, not the intensity of the attention. To illustrate, at a recent conference on safety in industrial organizations, the speaker from Alcoa pointed out that one of their former CEOs, Paul McNeill, wanted to get across to workers how important safety was and did this by insisting that the first item on every meeting agenda was to be a discussion of safety issues. In Alpha Power, supervisors start every job with a discussion of the safety issues they might encounter as part of the job briefing. The organization has many safety programs, and senior managers announce the importance of safety, but the message really gets across in the questions they ask on a daily basis.

Douglas McGregor (1960) tells of a company that wanted him to help install a management development program. The president hoped that McGregor would propose exactly what to do and how to do it. Instead, McGregor asked the president whether he really cared about identifying and developing managers. On being assured that he did, McGregor proposed that the president should build his concern into the reward system and set up a consistent way of monitoring progress; in other words, he should start to pay attention to it. The president agreed and announced to his subordinates that henceforth 50 percent of each senior manager ’s annual bonus would be contingent on what he had done to develop his own immediate subordinates during the past year. He added that he himself had no specific program in mind, but that in each quarter, he would ask each senior manager what had been done. You might think that the bonus was the primary incentive for the senior managers to launch programs, but far more important was the fact that they had to report regularly on what they were doing. The senior managers launched a whole series of different activities, many of them pulled together from work that was already going on piecemeal in the organization. A coherent program was forged over a two-year period and has continued to serve this company well. The president continued his quarterly questions and once a year evaluated how much each manager had done for development. He never imposed any program, but by paying consistent attention to management development and by rewarding progress, he clearly signaled to the organization that he considered management development to be important.

At the other extreme, some DEC managers illustrated how inconsistent and shifting attention causes subordinates to pay less and less attention to what senior management wants, thereby empowering the employee by default. For example, a brilliant manager in one technical group would launch an important initiative and demand total support, but two weeks later, he would launch a new initiative without indicating whether or not people were supposed to drop the old one. As subordinates two and three levels down observed this seemingly erratic behavior, they began to rely more and more on their own judgment of what they should actually be doing.

Some of the most important signals of what founders and leaders care about are sent during meetings and in other activities devoted to planning and budgeting, which is one reason why planning and budgeting are such important managerial processes. In questioning subordinates systematically on certain issues, leaders can transmit their own view of how to look at problems. The ultimate content of the plan may not be as important as the learning that goes on during the planning process.

For example, in his manner of planning, Smithfield (see Chapter Thirteen) made it clear to all his subordinates that he wanted them to be autonomous, completely responsible for their own operation, but financially accountable. He got this message across by focusing only on financial results. In contrast, both Sam Steinberg and Ken Olsen asked detailed questions about virtually everything during a planning process. Steinberg ’s obsession with store cleanliness was clearly signaled by the fact that he always commented on it, always noticed deviations from his standards, and always asked what was being done to ensure it in the future. Olsen’s assumption that a good manager is always in control of his own situation was clearly evident in his questions about future plans and his anger when plans did not reveal detailed knowledge of product or market issues.

Emotional Outbursts. An even more powerful signal than regular questions is a visible emotional reaction—especially when leaders feel that one of their important values or assumptions is being violated. Emotional outbursts are not necessarily very overt because many managers believe that they should not allow their emotions to become too involved in the decisionmaking process. But subordinates generally know when their bosses are upset, and many leaders do allow themselves to get overtly angry and use those feelings as messages.

Subordinates find their bosses’ emotional outbursts painful and try to avoid them. In the process, they gradually come to condition their behavior to what they perceive the leader to want, and if, over time, that behavior produces desired results, they adopt the leader’s assumptions. For example, Olsen’s concern that line managers stay on top of their jobs was originally signaled most clearly in an incident at an executive committee meeting when the company was still very young. A newly hired chief financial officer (CFO) was asked to make his report on the state of the business. He had analyzed the three major product lines and brought his analysis to the meeting. He distributed the information and then pointed out that one product line in particular was in financial difficulty because of falling sales, excessive inventories, and rapidly rising manufacturing costs. It became evident in the meeting that the vice president (VP) in charge of the product line had not seen the CFO’s figures and was somewhat embarrassed by what was being revealed.

As the report progressed, the tension in the room rose because everyone sensed that a real confrontation was about to develop between the CFO and the VP. The CFO finished, and all eyes turned toward the VP. The VP said that he had not seen the figures and wished he had had a chance to look at them; because he had not seen them, however, he had no immediate answers to give. At this point, Olsen blew up, but to the surprise of the whole group he blew up not at the CFO but at the VP. Several members of the group later revealed that they had expected Olsen to blow up at the CFO for his obvious grandstanding in bringing in figures that were new to everyone. However, no one had expected Olsen to turn his wrath on the product line VP for not being prepared to deal with the CFO ’s arguments and information. Protests that the VP had not seen the data fell on deaf ears. He was told that if he were running his business properly he would have known everything the CFO knew, and he certainly should have had answers for what should now be done.

Suddenly everyone realized that there was a powerful message in Olsen’s outburst. He clearly expected and assumed that a product-line VP would always be totally on top of his own business and would never put himself in the position of being embarrassed by financial data. The fact that the VP did not have his own numbers was a worse sin than being in trouble. The fact that he could not respond to the troublesome figures was also a worse sin than being in trouble. The Olsen blowup at the line manager was a far clearer message than any amount of rhetoric about delegation, accountability, and the like would have been.

If a manager continued to display ignorance or lack of control of his own situation, Olsen would continue to get angry at him and accuse him of incompetence. If the manager attempted to defend himself by noting that his situation either was the result of actions on the part of others over whom he had no control or resulted from prior agreements made by Olsen himself, he would be told emotionally that he should have brought the issue up right away to force a rethinking of the situation and a renegotiation of the prior decision. In other words, Olsen made it very clear, by the kinds of things to which he reacted emotionally, that poor performance could be excused but not being on top of one’s own situation and not informing others of what was going on could never be excused.

Olsen’s deep assumption about the importance of always telling the truth was signaled most clearly on the occasion of another executive committee meeting, when it was discovered that the company had excess inventory because each product line, in the process of protecting itself, had exaggerated its orders to manufacturing by a small percentage. The accumulation of these small percentages across all the product lines produced a massive excess inventory, which the manufacturing department disclaimed because it had only produced what the product lines had ordered. At the meeting in which this situation was reviewed, Olsen said that he had rarely been as angry as he was then because the product-line managers had lied. He stated flatly that if he ever caught a manager exaggerating orders again, it would be grounds for instant dismissal no matter what the reasons. The suggestion that manufacturing could compensate for the sales exaggerations was dismissed out of hand because that would compound the problem. The prospect of one function lying while the other function tried to figure out how to compensate for it totally violated Olsen’s assumptions about how an effective business should be run.

Both Steinberg and Olsen shared the assumption that meeting the customer’s needs was one of the most important ways of ensuring business success, and their most emotional reactions consistently occurred whenever they learned that a customer had not been well treated. In this area, the official messages, as embodied in company creeds and the formal reward system, were completely consistent with the implicit messages that could be inferred from founder reactions. In Sam Steinberg’ s case, the needs of the customer were even put ahead of the needs of the family, and one way that a family member could get in trouble was by mistreating a customer.

Inferences from What Leaders Do Not Pay Attention To. Other powerful signals that subordinates interpret for evidence of the leader ’s assumptions are what leaders do not react to. For example, in DEC, managers were frequently in actual trouble with cost overruns, delayed schedules, and imperfect products, but such troubles rarely caused comment if the manager had displayed evidenced that he or she was in control of the situation. Trouble was assumed to be a normal condition of doing business; only failure to cope and regain control was unacceptable. DEC ’s product design departments frequently had excess personnel, very high budgets, and lax management with regard to cost controls, but none of this occasioned much comment. Subordinates correctly interpreted this to mean that it was far more important to come up with a good product than to control costs.

Inconsistency and Conflict. If leaders send inconsistent signals in what they do or do not pay attention to, this creates emotional problems for subordinates, as was shown in the Steinberg case. Sam Steinberg valued high performance but accepted poor performance from family members, causing many competent nonfamily members to leave. Ken Olsen wanted to empower people, but he also signaled that he wanted to maintain “paternal” centralized control. Once some of the empowered engineering managers developed enough confidence in their own decision-making abilities, they were forced into a kind of pathological insubordination— agreeing with Olsen during the meeting but then telling me as we were walking down the hall after the meeting that “Ken no longer is on top of the market or the technology, so we will do something different from what he wants.” A young engineer coming into DEC would also find an organizational inconsistency in that the clear concern for customers coexisted with an implicit arrogance toward certain classes of customers because the engineers often assumed that they knew better what the customer would like in the way of product design. Olsen implicitly reinforced this attitude by not reacting in a corrective way when engineers displayed such arrogance.

The fact that leaders may be unaware of their own conflicts or emotional issues and, therefore, may be sending mutually contradictory messages leads to varying degrees of culture conflict and organizational pathology (Kets de Vries and Miller, 1987; Frost, 2003; Goldman, 2008). Both Steinbergs and DEC were eventually weakened by their leaders’ unconscious conflicts between a stated philosophy of delegation and decentralization and a powerful need to retain tight centralized control. Both intervened frequently on very detailed issues and felt free to go around the hierarchy. Subordinates will tolerate and accommodate contradictory messages because, in a sense, founders, owners, and others at higher levels are always granted the right to be inconsistent or, in any case, are too powerful to be confronted. The emerging culture will then reflect not only the leader’s assumptions but also the complex internal accommodations created by subordinates to run the organization in spite of or around the leader. The group, sometimes acting on the assumption that the leader is a creative genius who has idiosyncrasies, may develop compensatory mechanisms, such as buffering layers of managers, to protect the organization from the dysfunctional aspects of the leader’s behavior. In those cases, the culture may become a defense mechanism against the anxieties unleashed by inconsistent leader behavior. In other cases, the organization’s style of operating will reflect the very biases and unconscious conflicts that the founder experiences, thus causing some scholars to call such organizations “neurotic” (Kets de Vries and Miller, 1984, 1987). At the extreme, subordinates or the board of directors may have to find ways to move the founder out altogether, as has happened in a number of first-generation companies.

In summary, what leaders consistently pay attention to, reward, control, and react to emotionally communicates most clearly what their own priorities, goals, and assumptions are. If they pay attention to too many things or if their pattern of attention is inconsistent, subordinates will use other signals or their own experience to decide what is really important, leading to a much more diverse set of assumptions and many more subcultures.

Leader Reactions to Critical Incidents and Organizational Crises. When an organization faces a crisis, the manner in which leaders and others deal with it reveals important underlying assumptions and creates new norms, values, and working procedures. Crises are especially significant in culture creation and transmission because the heightened emotional involvement during such periods increases the intensity of learning. Crises heighten anxiety, and the need to reduce anxiety is a powerful motivator of new learning. If people share intense emotional experiences and collectively learn how to reduce anxiety, they are more likely to remember what they have learned and to ritually repeat that behavior to avoid anxiety.

For example, a company almost went bankrupt because it over-engineered its products and made them too expensive. The company survived by hitting the market with a lower quality, less expensive product. Some years later, the market required a more expensive, higher quality product, but this company was not able to produce such a product because it could not overcome its anxiety based on memories of almost going under with the more expensive high-quality product.

What is defined as a crisis is, of course, partly a matter of perception. There may or may not be actual dangers in the external environment, and what is considered to be dangerous is itself often a reflection of the culture. For purposes of this analysis, a crisis is what is perceived to be a crisis and what is defined as a crisis by founders and leaders. Crises that arise around the major external survival issues are the most potent in revealing the deep assumptions of the leaders.

A story told about Tom Watson, Jr., highlights his concern for people and for management development. A young executive had made some bad decisions that cost the company several million dollars. He was summoned to Watson’s office, fully expecting to be dismissed. As he entered the office, the young executive said, “I suppose after that set of mistakes you will be wanting to fire me.” Watson was said to have replied, “Not at all, young man, we have just spent a couple of million dollars educating you.”

Innumerable organizations have faced the crisis of shrinking sales, excess inventories, technological obsolescence, and the subsequent necessity of laying off employees to cut costs. How leaders deal with such crises reveals some of their assumptions about the importance of people and their view of human nature. Ouchi (1981) cites several dramatic examples in which U.S. companies faced with layoffs decided instead to go to short workweeks or to have all employees and managers take cuts in pay to manage the cost reduction without people reduction. We have seen many examples of this sort in the economic crisis of 2009.

The DEC assumption that “we are a family who will take care of each other” came out most clearly during periods of crisis. When the company was doing well, Olsen often had emotional outbursts reflecting his concern that people were getting complacent. When the company was in difficulty, however, Olsen never punished anyone or displayed anger; instead, he became the strong and supportive father figure, pointing out to both the external world and the employees that things were not as bad as they seemed, that the company had great strengths that would ensure future success, and that people should not worry about layoffs because things would be controlled by slowing down hiring.

On the other hand, Steinberg displayed his lack of concern for his own young managers by being punitive under crisis conditions, sometimes impulsively firing people only to have to try to rehire them later because he realized how important they were to the operation of the company. This gradually created an organization built on distrust and low commitment, leading good people to leave when a better opportunity came along.

Crises around issues of internal integration can also reveal and embed leader assumptions. I have found that a good time to observe an organization very closely is when acts of insubordination take place. So much of an organization’ s culture is tied up with hierarchy, authority, power, and influence that the mechanisms of conflict resolution have to be constantly worked out and consensually validated. No better opportunity exists for leaders to send signals about their own assumptions about human nature and relationships than when they themselves are challenged.

For example, Olsen clearly and repeatedly revealed his assumption that he did not feel that he knew best through his tolerant and even encouraging behavior when subordinates argued with him or disobeyed him. He signaled that he was truly depending on his subordinates to know what was best and that they should be insubordinate if they felt they were right. In contrast, a bank president with whom I have worked, publicly insisted that he wanted his subordinates to think for themselves, but his behavior belied his overt claim. During an important meeting of the whole staff, one of these subordinates, in attempting to assert himself, made some silly errors in a presentation. The president laughed at him and ridiculed him. Though the president later apologized and said he did not mean it, the damage had been done. All the other subordinates who witnessed the incident interpreted the outburst to mean that the president was not really serious about delegating to them and having them be more assertive. He was still sitting in judgment on them and was still operating on the assumption that he knew best.

How Leaders Allocate Resources. How budgets are created in an organization reveals leader assumptions and beliefs. For example, a leader who is personally averse to being in debt will bias the budget-planning process by rejecting plans that lean too heavily on borrowing and favoring the retention of as much cash as possible, thus undermining potentially good investments. As Donaldson and Lorsch (1983) show in their study of top- management decision making, leader beliefs about the distinctive competence of their organization, acceptable levels of financial crisis, and the degree to which the organization must be financially self-sufficient strongly influence their choices of goals, the means to accomplish them, and the management processes to be used. Such beliefs not only function as criteria by which decisions are made but are constraints on decision making in that they limit the perception of alternatives.

Olsen’s budgeting and resource allocation processes clearly revealed his belief in the entrepreneurial bottom-up system. He always resisted letting senior managers set targets, formulate strategies, or set goals, preferring instead to stimulate the engineers and managers below him to come up with proposals, business plans, and budgets that he and other senior executives would approve if they made sense. He was convinced that people would give their best efforts and maximum commitment only to projects and programs that they themselves had invented, sold, and were accountable for.

This system created problems as the DEC organization grew and found itself increasingly operating in a competitive environment in which costs had to be controlled. In its early days, the company could afford to invest in all kinds of projects whether they made sense or not. In the late 1980s, one of the biggest issues was how to choose among projects that sounded equally good when there were insufficient resources to fund them all. The effort to fund everything resulted in several key projects being delayed and this became one of the factors in DEC ’s ultimate failure as a business (Schein, 2003).

Deliberate Role Modeling, Teaching, and Coaching. Founders and new leaders of organizations generally seem to know that their own visible behavior has great value for communicating assumptions and values to other members, especially newcomers. Olsen and some other senior executives made videotapes that outlined their explicit philosophy, and these tapes were shown to new members of the organization as part of their initial training. However, there is a difference between the messages delivered by videos or from staged settings, such as when a leader gives a welcoming speech to newcomers, and the messages received when that leader is observed informally. The informal messages are the more powerful teaching and coaching mechanism.

Sam Steinberg, for example, demonstrated his need to be involved in everything at a detailed level by his frequent visits to stores and the minute inspections he made once he got there. When he went on vacation, he called the office every day at a set time and asked detailed questions about all aspects of the business. This behavior persisted into his semiretirement, when he would call every day from his retirement home thousands of miles away. Through his questions, his lectures, and his demonstration of personal concern for details, he hoped to show other managers what it meant to be highly visible and on top of one ’s job. Through his unwavering loyalty to family members, Steinberg also trained people in how to think about family members and the rights of owners. Olsen made an explicit attempt to downplay status and hierarchy in DEC by driving a small car, dressing informally, and spending many hours wandering among the employees at all levels, getting to know them personally.

An example of more explicit coaching occurred in Steinbergs when the Steinberg family brought back a former manager as the CEO after several other CEOs had failed. One of the first things this CEO did as the new president was to display at a large meeting his own particular method of analyzing the performance of the company and planning its future. He said explicitly to the group: “Now that’s an example of the kind of good planning and management I want in this organization.” He then ordered his key executives to prepare long-range plans in the format, which he had just displayed. He then coached their presentations, commented on each one, corrected the approach where he felt it had missed the point, and gave them new deadlines for accomplishing their goals as spelled out in the plans. Privately, he told an observer of this meeting that the organization had done virtually no planning for decades and that he hoped to institute formal strategic planning as a way of reducing the massive deficits that the organization had been experiencing. From his point of view, he had to change the entire mentality of his subordinates, which he felt required him to instruct, model, correct, and coach.

How Leaders Allocate Rewards and Status. Members of any organization learn from their own experience with promotions, from performance appraisals, and from discussions with the boss what the organization values and what the organization punishes. Both the nature of the behavior rewarded and punished and the nature of the rewards and punishments themselves carry the messages. Leaders can quickly get across their own priorities, values, and assumptions by consistently linking rewards and punishments to the behavior they are concerned with.

I am referring here to the actual practices—what really happens—not what is espoused, published, or preached. For example, product managers in General Foods were each expected to develop a successful marketing program for their specific product and then were rewarded by being moved to a better product after about eighteen months. Because the results of a marketing program could not possibly be known in eighteen months, what was really rewarded was the performance of the product manager in creating a “good” marketing program—as measured by the ability to sell it to the senior managers who approved it—not by the ultimate performance of the product in the marketplace.

The implicit assumption was that only senior managers could be trusted to evaluate a marketing program accurately; therefore, even if a product manager was technically accountable for his product, it was, in fact, senior management that took the real responsibility for launching expensive marketing programs. What junior managers learned from this was how to develop programs that had the right characteristics and style from senior management’s point of view. If junior-level managers developed the illusion that they really had independence in making marketing decisions, they had only to look at the relative insignificance of the actual rewards given to successful managers—they received a better product to manage, they might get a slightly better office, and they received a good raise— but they still had to present their marketing programs to senior management for review, and the preparations for and dry runs of such presentations took four to five months of every year even for very senior product managers. An organization that seemingly delegated a great deal of power to its product managers was, in fact, limiting their autonomy very sharply and systematically training them to think like senior managers.

To reiterate the basic point, if the founders or leaders are trying to ensure that their values and assumptions will be learned, they must create a reward, promotion, and status system that is consistent with those assumptions. Although the message initially gets across in the daily behavior of the leader, it is judged in the long run by whether the important rewards such as promotion are allocated consistently with that daily behavior.

The safety program in Alpha Power is a good example of the potential tension between espoused and actual rewards. The entire organization is geared to rewarding safe behavior on the job, and employees are encouraged to call time outs if they observe something unsafe. An expert is then brought in to make a judgment. Of course this takes time and reduces productivity, but safety is paramount. The employee and the supervisory level are rewarded for safe behavior, but the middle managers feel that their careers hinge more on how productive they are. This leaves the supervisors in an ambiguous and mixed incentive situation. They want to ensure safety, but they are also highly aware that their bosses while espousing safety will reward them for reliability and productivity.

Most organizations espouse a variety of values, some of which are intrinsically contradictory, so new employees must figure out for themselves what is really rewarded—customer satisfaction, productivity, safety, minimizing costs, or maximizing returns to the investors. Only by observing actual promotions and performance reviews can newcomers figure out what the underlying assumptions are by which the organization works.

How Leaders Select, Promote, and Excommunicate. One of the subtlest yet most potent ways through which leader assumptions get embedded and perpetuated is the process of selecting new members. For example, Olsen assumed that the best way to build an organization was to hire very smart, articulate, tough, independent people and then give them lots of responsibility and autonomy. Ciba-Geigy, on the other hand, hired very well educated, smart people who would fit into the more structured culture that had evolved over a century.

This cultural embedding mechanism is subtle because in most organizations it operates unconsciously. Founders and leaders tend to find attractive those candidates who resemble present members in style, assumptions, values, and beliefs. They are perceived to be the best people to hire and are assigned characteristics that will justify their being hired. Unless someone outside the organization is explicitly involved in the hiring, there is no way of knowing how much the current implicit assumptions are dominating recruiters’ perceptions of the candidates.

If organizations use search firms in hiring, an interesting question arises as to how much the search firm will understand some of the implicit criteria that may be operating. Because they operate outside the cultural context of the employing organization, do they implicitly reproduce or change the culture, and are they aware of their power in this regard? Basic assumptions are further reinforced through who does or does not get promoted, who is retired early, and who is, in effect, excommunicated by being fired or given a job that is clearly perceived to be less important, even if at a higher level (being “kicked upstairs”). In DEC, any employee who was not bright enough or articulate enough to play the idea-debating game and to stand up for his own ideas soon became walled off and eventually was forced out through a process of benign but consistent neglect. In Ciba-Geigy, a similar kind of isolation occurred if an employee was not concerned about the company, the products, and/or senior management. Neither company fired people except for dishonesty or immoral behavior, but in both companies such isolation became the equivalent of excommunication.

2. Primary Embedding Mechanisms: Some Concluding Observations

These embedding mechanisms all interact and tend to reinforce each other if the leader’s own beliefs, values, and assumptions are consistent. By breaking out these categories, I am trying to show the many different ways by which leaders can and do communicate their assumptions. Most newcomers to an organization have a wealth of data available to them to decipher the leader ’s real assumptions. Much of the socialization process is, therefore, embedded in the organization’ s normal working routines. It is not necessary for newcomers to attend special training or indoctrination sessions to learn important cultural assumptions. They become quite evident through the daily behavior of the leaders.

Source: Schein Edgar H. (2010), Organizational Culture and Leadership, Jossey-Bass; 4th edition.

Hi, Neat post. There is a problem together with your site in internet explorer, would check this… IE still is the market leader and a large component of other folks will miss your magnificent writing due to this problem.