1. Managerial Incentives and the Theory of Principal and Agent

When the provider of capital appoints a manager to decide how it should be used, an agency problem arises. In Chapter 5, it was seen that the nature of a contract between principal and agent will depend upon what can be observed, by whom, and at what cost. Let us suppose that the manager’s effort and the environment or ‘state of the world’ in which he or she is operating are unobservable to outsiders. The contract will then depend upon the ‘outcome’ alone, and the provisions for sharing the outcome between the two parties will depend upon the risk preferences of each. In other words, if a manager is to be given an incentive his or her reward must depend upon the outcome; in this case, the overall profit of the firm.

Figure 8.1 applies the theory of principal and agent to the relationship between the outside shareholder (in this case the principal) and the manager (here seen as the agent). If shareholdings are widely dispersed, S can be regarded as a ‘typical shareholder’ who is risk neutral in so far as the operation of the firm is concerned. The shareholder is interested only in the expected value of his or her profits from the firm. The manager (M) is risk averse and is, by assumption, unable to find insurance in the market because of the inability of insurers to observe states of the world any more easily than shareholders. This rules out contracts between a and t along the manager’s certainty line. Although ideal from the point of view of risk sharing, contracts on the manager’s certainty line will not induce effort. There may, however, exist a contract along the locus xw which will induce effort e from the manager of the shareholders’ funds. Contracts along xw imply some form of profit-related pay or stock ownership on the part of managers. If managers are risk averse, they will never take the entire risk, and hence we will not observe the manager effectively holding all residual claims and the provider of capital turning into a bondholder and lending at fixed interest (as at point ^ in Figure 8.1). Thus, the concentration of all residual claims in the monitor, as in the classical capitalist firm, is likely to exist only where capital requirements are small and monitors are risk neutral (see again the discussion of the single proprietorship in Chapter 4).

Contracts which link managerial rewards to profits will only work, of course, if the individual manager’s effort is actually capable of influencing the overall performance of the firm. In a ‘team’ environment where the individual contribution of each manager cannot be identified, the ‘public good trap’ will lead to shirking, and, as was seen in Chapter 4, contracts based upon ‘effort’ will be instituted. ‘Monitoring gambles’ and the hierarchical structures associated with them will become important, as described in Chapter 6. Eventually, however, the problem must be faced of who monitors the effort of the most senior managers? If shareholdings are dispersed the answer seems to be no one, and the house of cards erected in Chapter 6 falls down as predicted by Adam Smith. However, by giving senior managers at the apex of the hierarchy compensation packages which depend upon overall performance, effort incentives are provided. A manager low down the hierarchical structure will not find the holding of shares a great incentive to effort because the total profit of the enterprise may be imperceptibly affected by his or her behaviour. Senior managers are like the keystone in an arch, however. Take them away and collapse ensues; in place, the whole structure stands. Thus, the effort of top managers clearly will influence outcomes, and changes in the intensity of monitoring will permeate through the hierarchical structure. This argument is therefore based upon Alchian and Demsetz’s (1972) observation that monitors need an incentive to monitor, but it does not lead to the conclusion that the residual must be completely undiluted and assigned to a single person. All that is required is that incentives to top management are good enough for the joint-stock form, with its benefits of risk spreading and large team operations to prevail over alternative available institutional forms.

2. Some Early Studies of Managerial Contracts

The remuneration of senior executives is clearly a matter of great importance, and the evidence concerning the incentives built into various payment packages is still in dispute. At the heart of this long-running issue is disagreement about whether the interests of senior managers and directors are clearly associated with those of stockholders (for example, through direct stockholdings, stock options, pension entitlements, profit-related bonuses and so on) or whether, as Berle and Means asserted, managers have little reason to consider the shareholders and can pursue their own agenda. Early work by Sargant Florence (1961) for the UK and Villarejo (1961) for the USA pointed to the small percentage of shares held by directors in very large companies. The median holding was between one per cent and two per cent in the early 1950s. Managerial shareholding rose during the 1950s and 1960s, however, and the combined interest of corporate directors and management is often considerable. Demsetz (1983) reports that in the years 1973-82 the ownership interest of corporate directors and management was 19.3 per cent for the middle ten firms in the 1975 Fortune 500 list. For ten randomly selected firms too small to be included in the Fortune 500, the managerial interest was 32.5 per cent. It was in the very largest size range (the top ten firms), as would be expected, that the percentage interest of managers and directors fell to 2.1 per cent. Thus, ‘a substantial fraction of outstanding shares is owned by directors and management of corporations in all but the very largest firms’ (p. 388).

From the point of view of incentives, neither the combined shareholding of management nor the proportionate holding of senior managers is the most important factor, however. Of greater significance is the nature of the remuneration package of the most senior managers. Work in the early 1960s suggested that management income was more closely related to company size as measured by total sales than to company profits.10 McGuire, Chiu and Elbing (1962), for example, reported statistical correlations between executive compensation, profits and sales in a cross-section of firms in the period 1953-59. Their evidence supported a relationship between sales and executive incomes, although they cautiously warned that statistical problems meant that their tests ‘do not completely rule out the possibility of a valid relationship between profits and executive incomes too’ (p.760). By the early 1970s, cross-section studies of this nature were subjected to considerable criticism.11

Given the hierarchical structure of large firms, the internal incentive arrangement might be expected to result in a different scale of prizes for the contestants in a big tournament than a smaller one. This, though, would not permit us to deduce that, for a manager at the top of a given firm, an overriding incentive existed to increase the size of that particular hierarchy. A further criticism concerned the measure of executive incomes used. By concentrating on salaries, other important components were overlooked.

Masson (1971) constructed a measure of executive compensation which included deferred compensation such as stock options and retirement benefits as well as stock ownership, salary and bonuses. His sample consisted of the top three to five executives of thirty-nine electronics, aerospace and chemical companies for the years 1947-66. From these data, Masson concluded that executives receive a positive reward for increasing stock value, that changes in stock value are more important to the executive than changes in profit earned, and that the hypothesis that executives were paid to expand sales was rejected. Similar conclusions were reported by Lewellen (1969). In a survey of fifty of the largest five hundred US firms, Lewellen found that only about one-fifth of the total remuneration of the top executive came from salary. This study was followed by a further enquiry by Lewellen and Huntsman (1970). One of their measures of executive compensation included the ‘current income equivalent’ of various deferred and contingent pay schemes. In the case of a pension plan, for example, the extra salary necessary to buy equivalent cover from an insurance company was estimated and included as part of the comprehensive measure of managerial compensation. Their results indicated that ‘reported company profits appear to have a strong and persistent influence on executive rewards, whereas sales seem to have little, if any, such impact’ (p. 918). A surprising aspect of this finding was that it applied to the simpler measure of executive compensation (salary plus bonuses) as well as to the more sophisticated measure.

Meeks and Whittington (1975) concluded in contrast that managerial compensation was strongly correlated with sales in cross-section tests. Developing the point mentioned earlier, Meeks and Whittington did not, however, deduce from this that incentives are primarily in the direction of increasing size at the expense of profits. It is simply not open to managers or directors suddenly to choose to be as big as IBM or ICI in order to raise their salary. Although cross-section correlations are strong, large proportionate increases in size would be necessary to have a noticeable effect on a manager’s income. In practice, the manager does not choose the size of the firm but may have some influence over the rate of growth. When Meeks and Whittington considered the relative influence of higher growth and higher profits on managers’ rewards, however, their data suggested that profits were the more important.

3. Interpretative Problems and Some More Recent Studies

3.1. Executive stockholdings

More recent work, though increasingly sophisticated at a technical level, continues to reveal the difficulties of interpretation in this area. Cosh and Hughes (1987), for example, compare twenty-seven large UK companies from The Times 1000 with the same number of US companies from the Fortune list of the largest industrial corporations in 1981. The mean percentage of shares held beneficially and non-beneficially by Board Members was a mere 0.19 per cent in the UK sample compared with 5.7 per cent in the USA. These figures look small, especially in the UK. However, from a motivational point of view, small percentage holdings in extremely large companies can represent large personal wealth. Cosh and Hughes report that, in the USA 17.5 per cent of executive directors and 15.5 per cent of all directors were (pound sterling) millionaires simply through holdings of stock in the companies concerned. These figures rose to 33 per cent and 21 per cent respectively when stock options were included in the calculations. Directors in the USA can hardly be characterised as propertyless functionaries according to this evidence. On the other hand, it is clear that the situation in the UK in the early 1980s differed considerably from that in the USA. ‘In general, US CEOs (Chief Executive Officers) receive over 40 times the dividend income of their UK counterparts and the average director about 10 times as much’ (p. 303). Conyon and Murphy (2000) use 1997 data to confirm the finding that US chief executives receive higher total remuneration than those in the UK.12 The sensitivity of CEO remuneration to shareholder wealth was also higher in the USA, with the median CEO receiving around 1.5 per cent of increases in shareholder wealth compared with 0.25 per cent in the UK.

An important study of the US position is offered by Jensen and Murphy (1990b). In their sample of firms, the median holding of common stock by CEOs was 0.25 per cent. When the value of other components of the remuneration package such as bonuses, salary revisions, stock options, and performance-based dismissal decisions were added, Jensen and Murphy estimated that the CEO receives $3.25 for every $1000 increase in shareholder wealth.13 As a result of this low sensitivity of CEO remuneration to changes in shareholder wealth, ‘we believe that our results are inconsistent with the implications of formal agency models of optimal contracting’ (p. 227). Quite simply, the observed contract point seems too close to the CEO’s certainty line out of OMin Figure 8.1. Alternatively the ‘profit share’ or ‘piece-rate’ seems too small in terms of Figure 6.2 to be an optimal response to the principal-agent problem. This finding of a very small ‘pay- performance sensitivity’ is confirmed also in UK studies.14

Jensen and Murphy consider various escape routes from this quandary. Perhaps CEOs are easy to monitor after all and the shareholders have effective mechanisms for exerting direct control. We will be looking at this possibility in section 5. Perhaps CEOs cannot very much influence the welfare of shareholders by their efforts or their performance depends more on innate ability than on incentives. This, argue Jensen and Murphy, is inconsistent with evidence such as stock-price reactions to changes in CEOs which at least imply that the personality and efficiency of the CEO is important to the success or failure of the team. Perhaps the takeover threat is sufficient to motivate managers. But takeovers ‘may be a response to, instead of an efficient substitute for, ineffective internal incentives’ (p. 253). Unable to accept any of these explanations, Jensen and Murphy offer instead a ‘political’ answer. Sensational stories in the press and on television about ‘excessive’ executive compensation act as a disincentive to the introduction of suitable management contracts.

It is possible to argue, however, that Jensen and Murphy are too precipitate in their rejection of observed contracts as efficient responses to an agency problem. Cosh and Hughes’ point about the reaction of individual CEOs to absolutely large wealth effects (even if small in relation to the capitalisation of the company as a whole) needs to be taken more seriously.

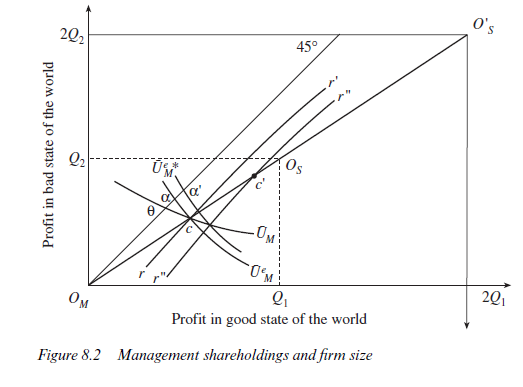

Consider Figure 8.2. A risk-averse agent (manager) runs a small company. Possible profit outcomes are Q1 (good) and Q2 (bad) respectively. Effort e, which, as in chapter 5, has the effect of increasing the probability of the good outcome, will be exerted by the agent at points along and to the right of the locus rr’. A contract prevails at c midway along the diagonal OMOS. Assume this is an optimal contract. It implies that the agent (manager) holds fifty per cent of the shares of the company. Now let the company double in size with the profit outcomes 2Q1 (good) and 2Q2 (bad). Under what circumstances would the contract at c still be an optimal contract? Suppose that effort level e had the same beneficial effect on the probability of the good outcome in the case of the big company as for the small company. The locus rr’ would be unchanged and c would confer the same expected utility to the manager whether he or she were in the big or the small company. The contract at c would be optimal in both cases. Yet, in the case of the big company, the agent (manager) holds only 25 per cent of the shares. Indeed, we might imagine the large company being one hundred times bigger than the small. In that case, on the assumption that effort e affects the probability distribution of the outcomes in the same way in large and small companies, a shareholding of 0.5 per cent would be optimal.

It will rightly be objected that the above model is oversimplified in its assumption of a dichotomous choice of ‘effort’ or ‘no effort’ on the part of the agent. However, the crucial assumption driving the result is, of course, that effort level e produces the same rise in the probability of the ‘good’ outcome in both large and small firms, even though the absolute size of the potential gain from achieving the good outcome is obviously much greater in the former compared with the latter. Effectively, the expected return to the team as a whole from the effort of the CEO is assumed to rise in proportion with the size of the firm.15 This permits the CEO to achieve the same expected personal return with a declining proportion of the outstanding shares. If the higher probability of the good outcome required more effort on the part of the CEO in the big compared with the small firm (let us say effort level e*), the locus rr’ would shift further away from the manager-agent’s certainty line (for example to r”r”) and the optimal contract might involve greater risk-sharing losses. The cost of effort would now be represented by distance 0a’. Even in this case, however, a contract at a point such as c’ in Figure 8.2 would imply a declining proportion of the firm’s shares held by the manager as the company grew.

The CEO’s effort can be regarded as a resource which reaches out through the organisation, increasing the productivity of the entire team. In the simplest formulation, a unit of CEO effort is a necessary ingredient to the more effective running of large and small teams – an overhead which is the same size for all firms. This might be rationalised in terms of strategic decision taking which may involve similar skills and effort in very different sizes of firm. To revert to the analogy of the ship at sea, the captain of a large oil tanker may use skills of a very similar order to those required on a smaller freighter, but the possible consequences for good or ill of his or her decisions will not be of the same order of magnitude. Alternatively, we might see the CEO as a motivator of others and a crucial influence on the ‘culture’ of the entire firm.16 The point here is that the CEO’s effort can produce indirect effects at some distance from the point of its initial application. The CEO sets a chain of events in motion by prodding into action the material closest to hand. The system as a whole gains momentum as limiting friction is overcome and each member of the team begins to exert force on the others.

Whether the above reasoning explains anything about the governance of the modern joint-stock enterprise is as much an empirical as a theoretical question. It does suggest the importance of recognising, however, that if CEO effort is highly effective at improving the probability distribution of outcomes, efficient personal incentives may be compatible with very small stockholdings as a proportion of the total stock issued. Haubrich (1994), for example, simulates ‘optimal’ contracts on the basis of plausible assumptions about risk preferences and effort costs and finds that ‘principal-agent theory can yield quantitative solutions in line with the empirical work of Jensen and Murphy’ (p. 259).

If effort is allowed to vary continuously, it might be expected that an efficient effort level for the CEO would be higher in a large firm than a small one. However, if the efficiency of effort is great in both cases, the optimal contract will be close to the agent’s certainty line (see Chapter 5). Now suppose there is: (i) rapidly falling marginal productivity of further effort (in terms of its effect on the probability distribution of possible outcomes); (ii) rapidly rising marginal disutility of effort; and (iii) risk aversion on the part of the CEO. All these factors will imply that a given rise in effort will require big shifts to the right in the locus rr’ of contracts capable of inducing it. As demonstrated in Chapter 5, these conditions are likely to imply the absence of Pareto improvements available from such contracts.

The above paragraphs have concentrated on reinterpreting the Jensen and Murphy findings in order to see whether they can after all be made compatible with principal-agent theory. However, some students of corporate governance cast doubt on the low pay-performance elasticity estimates of Jensen and Murphy. Hall and Liebman (1998) for example, use data on CEO compensation packages from the largest US firms. They report very high values of pay-performance sensitivity compared with Jensen and Murphy. Indeed, their median elasticity of compensation to firm value is 3.9 for 1994 – implying that a one per cent increase in firm value would result in a 3.9 per cent increase in CEO remuneration. The main factor driving this result appears to be the increase in the award of stock options during the 1980s and 1990s in the USA. The popularity of stock options during the 1990s is perhaps understandable given that the S&P 500 index rose by three hundred per cent during the decade.17

Stock options as a method of aligning the interests of managers with those of shareholders have been subject to some criticism, however.18 An option gives a manager the right to purchase stock at an agreed exercise price during a specified period of time (after which the option lapses). Permitting the manager to determine the date of exercise of the option thus gives him/her a chance to speculate on general market movements, taking his/her profit while options are ‘in the money’ and when s/he judges conditions to be favourable. The incentive effects of this instrument are not, therefore, very focused. Further, there is a paradoxical side to the operation of stock options. If they are expected to motivate managers successfully, the present value of expected future profits will rise and so also will the value of the firm on the market. However, where a manager can exercise his/her options fairly soon after they have been granted, s/he might realise his/her gain quickly before much of his/her anticipated effort has been made. Presumably, an efficient market would allow for this effect in evaluating the incentive effects of the options in the first place, but options are clearly not a simple method of aligning managerial and ownership interests. Critics have suggested, for example, that an exercise date should be specified in the contract and that the value should be linked to relative performance against other firms in the same sector.19

Stock options can also be criticised from precisely the opposite perspective compared with Jensen and Murphy. In other words, they can imply a contract point too far from the agent’s certainty line rather than too close. If an agent is risk averse, there will be a risk-bearing cost to this uncertainty. Especially where the riskiness of the stock is very great, the value of options to a manager can be well below the cost to the firm of awarding them. Outside equity holders in the firm might be well diversified whereas a manager whose remuneration depends substantially on stock options is not.20

3.2. Trading on inside information

At this point, it is convenient to look briefly at another possible incentive device – trading on inside information. The law takes a dim view of such activities in many countries and it is widely considered that insider dealing is undesirable. The Criminal Justice Act in the United Kingdom, for example, makes it a crime to deal, or to procure or encourage another to deal, on the basis of inside information.21 The United States has a similarly restrictive legal background while the European Community has issued an important Directive on Insider Dealing.22

Justifications for this restrictive legislation are based on grounds of efficiency, the protection of property rights, and of straightforward fairness. If market makers dealing in stocks and shares frequently face better- informed ‘insiders’, it is claimed that they risk losing heavily in their trading activities with these parties and will be inhibited from trading.23 Adverse selection will mean that the market will be less developed than it would be with symmetrical information – an application of the ‘lemons’ principle which was introduced in Chapter 2. The property rights argument relies upon a traditional view of the joint-stock enterprise (see again section 2.1) with shareholders as the rightful ‘owners’ of information accruing to the employees and managers in the course of their duties. According to this argument, insider dealers are attempting to steal some of the profits that belong rightfully to the shareholders. Finally, the idea of better-informed traders gaining at the expense of the unwary or misinformed by buying or selling assets at prices they know to be ‘false’ is not acceptable to some people, even when the trading is conducted on vast and impersonal stock markets.

Each of these arguments is open to serious objections. Firstly, restrictions on insider dealing could mean that the prices of assets on the stock market do not reflect the full information potentially available and that market efficiency is thereby impaired.24 A celebrated exposition of this view can be found in Henry Manne (1966). Secondly, if shareholders wish to negotiate contracts with their managers permitting them to trade on inside information as part of an incentive package, breach of trust would not be involved. Finally, all entrepreneurial activity and the social benefits deriving from it relies on some people thinking they have better information than others. To abolish trade in the presence of asymmetrically distributed knowledge would be to abolish the entrepreneurial process entirely.25 Indeed, the more we are inclined to accept Wu’s conception of the firm as a coalition of entrepreneurs, the more important it becomes to provide a mechanism which enables them to claim entrepreneurial profits. Manne (1966) argued, for example, that ‘profits from insider trading constitute the only effective compensation scheme for entrepreneurial services in large corporations’ (p. 116). However, the logic of Wu’s approach would not seem to suggest the use of insider trading. If shareholders receive a regular flow of dividends and have no claim to the ‘pure entrepreneurial profits’, share prices would be expected to be fairly stable, and surplus profits would presumably be received by the entrepreneurs in the form of bonuses, profit- related pay, pension rights and stock options.

Even in the context of the agency model of the joint-stock company, allowing insider dealing as a means of giving incentives to managers is not a straightforward way of aligning managerial and shareholder interests. Profits are made on securities markets by having better information than other people, but this applies to information about bad financial results as well as good results. The ability of an informed insider to profit from advance knowledge of bad trading results by a policy of selling the shares short would not be compatible with providing incentives to managers to avoid these results. Shareholders would presumably wish managers to benefit from diligence and skill in their jobs rather than from the simple privilege of gaining access to information first. Stock options, or the ownership of stock with restrictions on the right to trade for a specified period of time would therefore appear to be more effectively structured incentive devices. Managers can then only gain from ensuring a rise in the price of the stock over the long run.

Source: Ricketts Martin (2002), The Economics of Business Enterprise: An Introduction to Economic Organisation and the Theory of the Firm, Edward Elgar Pub; 3rd edition.

Great website. A lot of helpful info here. I?¦m sending it to some friends ans also sharing in delicious. And naturally, thanks in your effort!