Physical distribution starts at the factory. Managers choose a set of warehouses (stocking points) and transportation carriers that will deliver the goods to final destinations in the desired time or at the lowest total cost. Physical distribution has now been expanded into the broader concept of supply chain management (SCM). Supply chain management starts before physical distribution and includes strategically procuring the right inputs (raw

materials, components, and capital equipment), converting them efficiently into finished products, and dispatching them to the final destinations. An even broader perspective looks at how the company’s suppliers themselves obtain their inputs.

The supply chain perspective can help a company identify superior suppliers and distributors and then help it improve productivity and reduce costs. Firms with top supply chains include Apple, McDonald’s, Amazon.com, Unilever, Intel, Procter & Gamble, Cisco Systems, and Samsung Electronics.65 Some companies choose to partner with and outsource to third-party logistics specialists for help with transportation planning, distribution center management, and other valued-added services that go beyond shipping and storing.66

Getting the supply chain right can have huge payoffs. In 2005, Whirlpool found itself with a hodgepodge of warehouses, transport depots, and factory-distribution centers. After a four-year, $600 million investment in a new state-of-the-art distribution system built from scratch, the company reduced its annual inventory by about $250 million a year and now realizes a savings of $100 million a year in increased efficiency while being able to deliver products in 48 to 72 hours.67

Market logistics includes planning the infrastructure to meet demand, then implementing and controlling the physical flows of materials and final goods from points of origin to points of use to meet customer requirements at a profit. Market logistics planning has four steps:68

- Deciding on the company’s value proposition to its customers. (What on-time delivery standard should we offer? What levels should we attain in ordering and billing accuracy?)

- Selecting the best channel design and network strategy for reaching the customers. (Should the company serve customers directly or through intermediaries? What products should we source from which manufacturing facilities? How many warehouses should we maintain, and where should we locate them?)

- Developing operational excellence in sales forecasting, warehouse management, transportation management, and materials management

- Implementing the solution with the best information systems, equipment, policies, and procedures

Studying market logistics leads managers to find the most efficient way to deliver value. For example, a software company traditionally produced and packaged software disks and manuals, shipped them to wholesalers, which shipped them to retailers, which sold them to customers, who brought them home to download onto their PCs. Market logistics offered two superior delivery systems. The first let the customer download the software directly onto his or her computer. The second allowed the computer manufacturer to download the software onto its products. Both solutions eliminated the need for printing, packaging, shipping, and stocking millions of disks and manuals and have quickly become the norm of the industries.

1. INTEGRATED LOGISTICS SYSTEMS

The market logistics task calls for integrated logistics systems (ILS), which include materials management, material flow systems, and physical distribution, aided by information technology (IT). Information systems play a critical role in managing market logistics, especially via computers, point-of-sale terminals, uniform product bar codes, satellite tracking, electronic data interchange (EDI), and electronic funds transfer (EFT). These developments have shortened the order-cycle time, reduced clerical labor, reduced errors, and provided improved control of operations. They have enabled companies to promise “the product will be at dock 25 at 10:00 am tomorrow” and to deliver on that promise.

Market logistics encompass several activities. The first is sales forecasting, on the basis of which the company schedules distribution, production, and inventory levels. Production plans indicate the materials the purchasing department must order. These materials arrive through inbound transportation, enter the receiving area, and are stored in raw-material inventory. Raw materials are converted into finished goods. Finished-goods inventory is the link between customer orders and manufacturing activity. Customers’ orders draw down the finished-goods inventory level, and manufacturing activity builds it up. Finished goods flow off the assembly line and pass through packaging, in-plant warehousing, shipping-room processing, outbound transportation, field warehousing, and delivery and service.

Management has become concerned about the total cost of market logistics, which can amount to as much as 30 to 40 percent of the product’s cost. In the U.S. grocery business, waste or “shrink” affects 8 to 10 percent of perishable goods, costing $20 billion annually. Stop & Shop, a $16 billion grocery chain, discovered that large, mountainous displays of fruits and veggies and other perishables don’t necessarily equal more sales. Instead it often led to spoilage on the shelf, displeasing customers and requiring more staff to sort out the perished items. After an analysis of the perishable departments, Stop & Shop cut the number of foods on display—8 avocados instead of 24, 4 salmon filets instead of 12, for example—and saved an estimated annual $100 million by reducing shrink and improving customer satisfaction. 69

Many experts call market logistics “the last frontier for cost economies,” and firms are determined to wring every unnecessary cost out of the system: In 1982, logistics represented 14.5 percent of U.S. GDP; by 2012, the share had dropped to about 8.5 percent.70 Lowering these costs yields lower prices, higher profit margins, or both. Even though the cost of market logistics can be high, a well-planned program can be a potent tool in competitive marketing.

Many firms are embracing lean manufacturing, originally pioneered by Japanese firms such as Toyota, to produce goods with minimal waste of time, materials, and money. CONMED’s disposable devices are used by a hospital somewhere in the world every 90 seconds to insert and remove fluid around joints during orthoscopic surgery.71

CONMED To streamline production, medical manufacturer CONMED set out to link its operations as closely as possible to the ultimate buyer of its products, applying lean manufacturing and Six Sigma philosophies to boost productivity, improve its use of floor space, and cut inventory. Rather than moving manufacturing to China, which might have lowered labor costs but could have also risked long lead times, inventory buildup, and unanticipated delays, the firm put new production processes into place to assemble its disposable products only after hospitals placed orders. Some 80 percent of orders were predictable enough that demand forecasts updated every few months could set hourly production targets. As proof of CONMED’s new efficiency, the assembly area for fluid-injection devices went from covering 3,300 square feet and stocking $93,000 worth of parts to 650 square feet and $6,000 worth of parts. Output per worker increased 21 percent. Similarly, its shaver blade factory increased production while decreasing costs by as much as 30 percent in some cases.

Lean manufacturing must be implemented thoughtfully and monitored closely. Toyota’s crisis in product safety, which resulted in extensive product recalls, has been attributed in part to the fact that some aspects of lean manufacturing—eliminating overlap by using common parts and designs across multiple product lines and reducing the number of suppliers to procure parts with greater economies of scale—can backfire when quality-control issues arise.

2. MARKET-LOGISTICS OBjECTIVES

Many companies state their market-logistics objective as “getting the right goods to the right places at the right time for the least cost” Unfortunately, this objective provides little practical guidance. No system can simultaneously maximize customer service and minimize distribution cost. Maximum customer service implies large inventories, premium transportation, and multiple warehouses, all of which raise market-logistics costs.

Nor can a company achieve market-logistics efficiency by asking each market-logistics manager to minimize his or her own logistics costs. Market-logistics costs interact and are often negatively related. For example:

- The traffic manager favors rail shipment over air shipment because rail costs less. However, because the railroads are slower, rail shipment ties up working capital longer, delays customer payment, and might send customers to competitors who offer faster service.

- The shipping department uses cheap containers to minimize shipping costs. Cheaper containers lead to a higher rate of damaged goods and customer ill will.

- The inventory manager favors low inventories. This increases stock-outs, back orders, paperwork, special production runs, and high-cost, fast-freight shipments.

Given these trade-offs, managers must make decisions on a total-system basis. The starting point is to study what customers require and what competitors are offering. Customers are interested in on-time delivery, help meeting emergency needs, careful handling of merchandise, and quick return and replacement of defective goods.

The wholesaler must then research the relative importance of these service outputs. For example, service-repair time is very important to buyers of copying equipment. Xerox developed a service delivery standard that “can put a disabled machine anywhere in the continental United States back into operation within three hours after receiving the service request.” It then designed a service division of technicians, parts, and locations to deliver on this promise.

The company must also consider competitors’ service standards. It will normally want to match or exceed these, but the objective is to maximize profits, not sales. Some companies offer less service and charge a lower price; other companies offer more service and charge a premium price.

The company ultimately must establish some promise it makes to the market. Some companies define standards for each service factor. One appliance manufacturer promises to deliver at least 95 percent of the dealer’s orders within seven days of order receipt, to fill them with 99 percent accuracy, to deal with inquiries about order status within three hours, and to ensure that merchandise damaged in transit does not exceed 1 percent.

3. MARKET-LOGISTICS DECISIONS

The firm must make four major decisions about its market logistics: (1) How should we handle orders (order processing)? (2) Where should we locate our stock (warehousing)? (3) How much stock should we hold (inventory)? and (4) How should we ship goods (transportation)?

ORDER PROCESSING Most companies today are trying to shorten the order-to-payment cycle—that is, the time between an order’s receipt, delivery, and payment. This cycle has many steps, including order transmission by the salesperson, order entry and customer credit check, inventory and production scheduling, order and invoice shipment, and receipt of payment. The longer this cycle takes, the lower the customer’s satisfaction and the lower the company’s profits.

WAREHOUSING Every company must store finished goods until they are sold because production and consumption cycles rarely match. More stocking locations mean goods can be delivered to customers more quickly, but warehousing and inventory costs are higher. To reduce these costs, the company might centralize its inventory in one place and use fast transportation to fill orders. To better manage inventory, many department stores such as Nordstrom and Macy’s now ship online orders from individual stores.73

Some warehouses are now taking on activities formerly done in the plant, including product assembly, packaging, and construction of promotional displays. Moving these activities to the warehouse can save costs and match the offerings more closely to demand.

INVENTORY Salespeople would like their companies to carry enough stock to fill all customer orders immediately. However, this is not cost effective. Inventory cost increases at an accelerating rate as the customer- service level approaches 100 percent. Management needs to know how much sales and profits would increase as a result of carrying larger inventories and promising faster order fulfillment times and then make a decision.

As inventory draws down, management must know at what stock level to place a new order. This stock level is called the order (or reorder) point. An order point of 20 means reordering when the stock falls to 20 units. The order point should balance the risks of stock-out against the costs of overstock. The other decision is how much to order. The larger the quantity ordered, the less frequently an order needs to be placed.

The company needs to balance order-processing costs and inventory-carrying costs. Order-processing costs for a manufacturer consist of setup costs and running costs (operating costs when production is running) for the item. If setup costs are low, the manufacturer can produce the item often, and the average cost per item is stable and equal to the running costs. If setup costs are high, however, the manufacturer can reduce the average cost per unit by producing a long run and carrying more inventory.

Order-processing costs must be compared with inventory-carrying costs, which include storage charges, cost of capital, taxes and insurance, and depreciation and obsolescence. Carrying costs might run as high as 30 percent of inventory value and are higher the larger the average stock carried. This means marketing managers who want to carry larger inventories need to show that incremental gross profits will exceed incremental carrying costs.

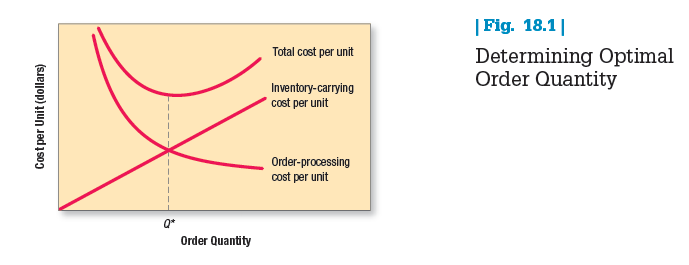

We can determine the optimal order quantity by observing how order-processing costs and inventory-carrying costs add up at different order levels. Figure 18.1 shows that the order-processing cost per unit decreases as the number of units ordered increases because the order costs are spread over more units. Inventory-carrying charges per unit increase with the number of units ordered because each unit remains longer in inventory. We sum the two cost curves vertically into a total-cost curve and project the lowest point of the total-cost curve on the horizontal axis to find the optimal order quantity Q .74

Companies are reducing their inventory costs by treating inventory items differently, keeping slow-moving items in a central location and carrying fast-moving items in warehouses closer to customers. Managers are also considering inventory strategies that give them flexibility should anything go wrong, as it often does, whether a dock strike in California, an earthquake in Japan, or political turmoil in North Africa and the Middle East. In an interconnected world, one weak link, if not properly managed, can bring down the entire supply chain.75

The ultimate answer to carrying near-zero inventory is to build for order, not for stock. Sony calls it SOMO, “Sell one, make one.” Dell’s inventory strategy for years has been to get the customer to order a computer and pay for it in advance. Then Dell uses the customer’s money to pay suppliers to ship the necessary components. As long as customers do not need the item immediately, everyone can save money. Some retailers are unloading excess inventory on eBay where, by cutting out the liquidator middleman, they can make 60 to 80 cents on the dollar as opposed to 10 cents.76 And some suppliers are snapping up excess inventory to create opportunity. 77

CAMERON HUGHES “If a winery has an eight-barrel lot, it may only use five barrels for its customers,” says Cameron Hughes, a wine negotiant who buys excess juice from high-end wineries and wine brokers in France, Italy, Spain, Argentina, South Africa, and California and combines it to make limited-edition, premium blends that taste much more expensive than their price tags. A $100 California Cabernet may sell for $25 a bottle or less under his Lot 500 Napa Valley Cabernet Savignon label. Negotiants have been around a long time, first as intermediaries who sold or shipped wine as wholesalers, but the profession has expanded as opportunists such as Hughes began making their own wines. Hughes doesn’t own any grapes, bottling machines, or trucks. He outsources the bottling, and he sells directly to retailers such as Costco, Sam’s Club, and Safeway, eliminating intermediaries and multiple markups. Hughes never knows which lots of wine he will have or how many, but he’s turned uncertainty to his advantage—he creates a new product with every batch. Rapid turnover is part of Costco’s appeal for him. The discount store’s customers love the idea of finding a rare bargain, and Hughes promotes his wines through in-store wine tastings and insider e-mails about his upcoming numbered lots, which sell out quickly. One thing customers won’t find out is exactly where the wine comes from. In signing deals Hughes typically has to accept non-disclosure agreements prohibiting him from naming his sources, though the Cameron Confidential flyer that accompanies each wine may hint at it.

TRANSPORTATION Transportation choices affect product pricing, on-time delivery performance, and the condition of the goods when they arrive, all of which affect customer satisfaction.

In shipping goods to its warehouses, dealers, and customers, a company can choose rail, air, truck, waterway, or pipeline. Shippers consider such criteria as speed, frequency, dependability, capability, availability, traceability, and cost. For speed, the prime contenders are air, rail, and truck. If the goal is low cost, then the choice is water or pipeline.

Shippers are increasingly combining two or more transportation modes, thanks to containerization. Containerization consists of putting the goods in boxes or trailers that are easy to transfer between two transportation modes. Piggyback describes the use of rail and trucks; fishyback, water and trucks; tranship, water and rail; and airtruck, air and trucks. Each coordinated mode offers specific advantages. For example, piggyback is cheaper than trucking alone yet provides flexibility and convenience.

Shippers can choose private, contract, or common carriers. If the shipper owns its own truck or air fleet, it becomes a private carrier. A contract carrier is an independent organization selling transportation services to others on a contract basis. A common carrier provides services between predetermined points on a scheduled basis and is available to all shippers at standard rates. Some contract carriers are investing and innovating to create strong value propositions.78

CONTRACT CARRIERS With so many transportation options available, firms in those industries are constantly competing to cut costs, improve services, and offer even more value to their shipping customers. After 10 years and billions of dollars in investment, including $2.5 billion in 2010 alone, Union Pacific saw on-time delivery on its railroads increase from 30 percent to roughly 90 percent. Improving reliability is also important in ocean shipping. Copenhagen-based Maersk Group is the world’s largest global shipper, with around 550 container ships and 225 tankers. To improve efficiency, the firm in 2014 commissioned 20 of the largest ships ever built. Costing $185 million each, these giant ships can cost-effectively carry 18,000 containers, also emitting 50 percent less CO2 in the process. Schneider, one of the country’s largest full-truckload freight haulers with more than $3 billion in revenue, developed a fleet-wide “tactical simulator” that has saved the company tens of millions of dollars. Besides helping in the crucial day-to-day route scheduling for drivers, the simulator has also helped with specific decisions ranging from when to raise prices for certain customers to how many drivers to hire (and where). Little changes can make big differences for shippers. Global logistics leader UPS calculated that by having its drivers use a fob instead of a key to operate its trucks, it is cutting out on average 1.7 seconds per stop, or 6.5 minutes per day, saving an estimated $70 million a year in the process.

To reduce costly handing at arrival, some firms are putting items into shelf-ready packaging so they don’t have to unpack them from a box and place them individually on a shelf. In Europe, P&G has used a three-tier logistic system to schedule deliveries of fast- and slow-moving goods, bulky items, and small items in the most efficient way.79 To reduce damage in shipping, the size, weight, and fragility of the item must be reflected in the crating technique used and the density of foam cushioning.80 With logistics, every little detail must be reviewed to see how it might be changed to improve productivity and profitability.

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

It¦s actually a great and useful piece of information. I¦m satisfied that you simply shared this helpful info with us. Please stay us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.