1. The introduction

What is said in the introduction to an interview is crucial in securing the cooperation of respondents. This is true for both interviewer-administered surveys and self-completion studies.

From an ethical standpoint the introduction should include:

- the name of the organization conducting the study;*

- the broad subject area;

- whether the subject area is particularly sensitive;

- whether the data collected will be held confidentially or used at a personally identifiable level for other purposes such as database building or direct marketing, and if so by whom and for what purposes;*

- the likely length of the interview;

- any cost to the respondent;

- whether the interview is to be recorded, either audio or video, other than for the purposes of quality control.*

The items marked * are required by the Data Protection Act 1998 in the UK.

This gives respondents or potential respondents the information that they require in order to be able to make an informed decision about whether or not they are prepared to cooperate in the study.

Sometimes it is not easy to comply with these requirements, but the questionnaire writer should make every effort to do so.

2. Name of the research organization

The name of the organization carrying out the study would usually be the research company that is responsible for writing the questionnaire if that is the same as the company that will be responsible for analysis of the results. (In UK Data Protection Act terms, this is the Data Controller.) If part or all of the fieldwork is to be subcontracted, then the name of the subcontracting agency need not be mentioned, providing that it is passing on completed interviews to the main agency for processing, and it is possible to identify individual interviewers in case of a complaint being made.

3. Subject matter

The broad subject area should be given so that the respondent has a reasonable idea of the area of questioning that is to follow. Frequently we do not wish to reveal the precise subject matter too early as this will bias responses, particularly during the screening questions. However, every effort should be made to give a general indication. For example, a survey about holidays could be described as being about leisure activities, although such a description may be inadequate for a survey about drinking habits. ‘Leisure activities’ would certainly be an inadequate description for a survey about sexual activity, which is regarded as a sensitive subject.

4. Sensitive questions

In the UK sensitive subjects are defined as including:

- sexual activity;

- racial origin;

- political opinions;

- religious or similar beliefs;

- physical or mental health;

- implication in criminal activity;

- trade union membership.

This list, though, is not exhaustive in terms of what respondents may find sensitive, and the questionnaire writer should examine the study for any possible sensitive content. Anyone working in areas dealing with drugs and medication, or illness, or conducting studies on financial topics should be particularly alert to this issue.

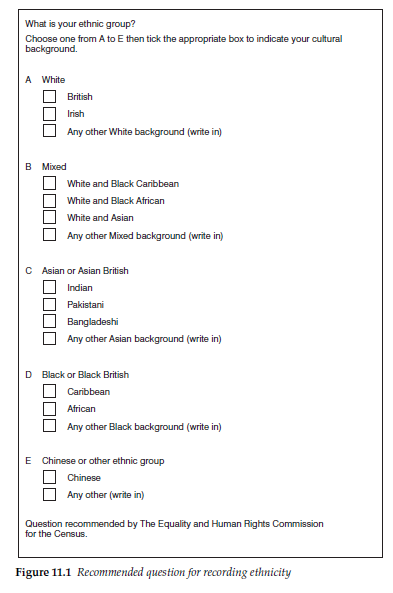

If you need to determine the ethnicity of respondents, then The Market Research Society suggests use of the question used in the Census and recommended by The Equality and Human Rights Commission, shown in Figure 11.1. This question is only applicable to the UK, as it reflects the ethnic make up of that country. For other countries different categories will be required both to reflect the prevalence of different ethnic groupings and to reflect any different use of acceptable terminologies. Within the UK it may be necessary to amend the categories for localities where a more detailed description is required, or within the nations of the UK it may be necessary to distinguish between English, Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish.

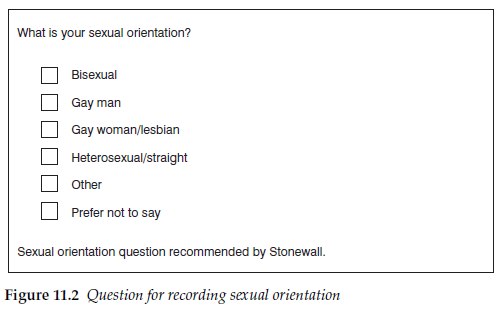

Sexual orientation is not an issue that requires to be asked about frequently in market research but there are occasions when it might be necessary. It can be a very personal and private issue, and it is important to get the correct wording so as not to offend, and to encourage as many people as possible to answer. Stonewall, the pressure group (www.stonewall.org.uk), recommend the question shown in Figure 11.2 for asking about sexual orientation. An alternative is to provide one category for lesbian/gay and cross-analyse by gender if necessary. It is, of course, important to include a ‘Prefer not to say’ option for all sensitive questions.

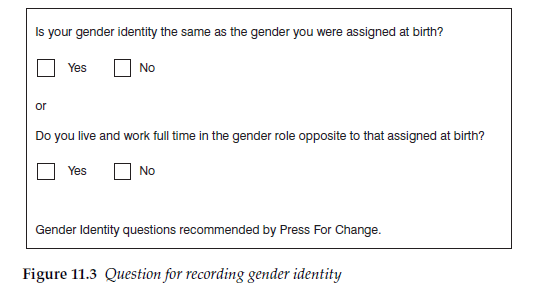

Gender identity is also an issue that is only rarely asked about in commercial research, but that may be relevant for certain social research issues or social advertising research. The question in Figure 11.3 is recommended by Press For Change (www.pfc.org.uk). They recommend the use of these descriptive questions rather than questions which rely on terminologies or labels which could offend.

Like all sensitive issues, race, sexual orientation and gender identity should never be asked about unless it is absolutely necessary for the purposes of the study.

4.1. Confidentiality

One of the key distinctions between market research surveys and surveys carried out for direct marketing or database building is that the data are held confidentially and are for analysis purposes only. No direct sales or marketing activity will take place as a result of the respondent having taken part in the study. If this is the case, this should be stated in the introduction on the questionnaire or in the covering letter in the case of a postal survey. It is then the responsibility of the research organization to ensure that the data are treated solely in this way.

Sometimes, research organizations carry out studies that are not confidential research. Some customer satisfaction surveys utilize individual- level data to enhance the client company’s customer database or to allow selective marketing to customers, dependent on their recorded level of satisfaction. Or research may be used to identify respondents who show an interest in a new product or service that the client can follow up with marketing activity. The latter may occur particularly in small business-to- business markets, where most or all of the potential market is included in the study. Such studies are not confidential research and the questionnaire must not represent them as such.

Apart from it being against the Data Protection Act in the UK to represent such studies as confidential research, it is morally wrong to mislead respondents. It is also bad for the image of market research if respondents are wrongly led into thinking that nothing will occur to them as result of participating in the study. It can only damage response rates for future surveys if respondents become disillusioned about the reassurances that they are given.

4.2. Interview length

How long the interview is likely to take is another area where a respondent once misled is unlikely to trust future assurances. One of the most common causes of complaints received by the Market Research Society from members of the public is that the interview in which they participated took significantly longer than they were initially told. Sometimes they were not told how long the interview would take, and wrongly assumed that it would be only a few minutes. On other occasions, though, they were told the likely duration of the interview, which was then significantly exceeded.

Sometimes it is straightforward to estimate the length of the interview. When the study has a questionnaire with a simple flow path and little routeing, the pilot survey will have demonstrated how long it will take, and that is likely to be about the same for all respondents.

The time required to complete the interview can vary considerably between respondents as the questionnaire becomes more complex. It can depend on the speed with which respondents answer the questions and the amount of consideration that they give to each. It can also vary significantly depending on the answers that they give. The questionnaire may contain sections that are asked only if the respondent displays a particular behaviour, knowledge or attitude at an earlier question. The time taken to complete the interview can increase or decrease considerably, depending on whether or not such sections are asked. The eligibility of any individual respondent for these sections cannot be predicted at the outset of the interview, with the consequence that the interview length could vary between, say, 15 minutes and 45 minutes for different respondents.

If there is likely to be a significant variation in interview length between respondents, then the questionnaire writer should try to reflect this in the introduction.

The introduction must never deliberately understate the likely time required. It is better to be vague about the interview length than deliberately to mislead.

4.3. Source of name

Respondents have a right to know how they were sampled or where the research organization obtained their name and contact details. For surveys using non-pre-selected samples, this does not usually present any difficulties, although explaining how random digit dialling works to someone who is ex-directory can sometimes be difficult.

Where the names have been supplied from a database, this can sometimes present more of a problem. With customer satisfaction surveys, we shall often want to say in the introduction that respondents have been contacted because they are customers of the organization. Frequently, clients will see the customer satisfaction survey as a way of demonstrating to their customers that the organization cares about the relationship between them. Then it is not uncommon for the introduction to state this and for postal or web-based satisfaction questionnaires to include client identification and logos.

However, sometimes we do not wish to reveal the source at the beginning of the interview because that may bias responses to questions where the client organization is to be compared against similar organizations. If, in a personal interview, the interviewer is asked the source before these questions arise, the respondent can be asked to wait until later in the interview or until the end of the interview for that to be revealed. An explanation of why the respondent is being asked to wait until then should also be given. If the respondent refuses to continue unless he or she is told, then they must be told and the interview terminated. Instructions to interviewers to this effect may appear on the questionnaire, or may be included in their training or in separate instructions.

Web-based surveys can carry a similar promise to reveal the name of the client at the end of the interview if it is thought that not to do so might reduce response rates. For postal surveys, this is not possible.

4.4. Cost to respondent

If taking part in the interview is going to cost the respondents anything other than their time, this must be pointed out. In practice it is usually only internet or web-based interviews that are likely to incur cost for the respondent (Nancarrow, Pallister and Brace, 2001) and then only if they are paying for their internet connection on a per-minute basis. Occasionally, though, respondents will be asked to incur travel costs in order to reach a central interviewing venue such as a new product clinic. These costs, though, would normally be reimbursed.

Calling respondents on a mobile phone could also incur a cost for them. If they happen to be abroad at the time that cost could be significant. The questionnaire introduction should always establish not only whether it is safe for respondents to talk on their mobile phones, but also whether doing so is likely to incur any costs for them.

5. During the interview

5.1. Right not to answer

Researchers must always remember that respondents have agreed to take part in the study voluntarily. Should they wish not to answer any of the questions put to them, or to withdraw completely from the interview, they cannot be compelled to do otherwise. Part of the art of the interviewer is to minimize such occurrences by striking up a relationship so that respondents continue for the sake of the interviewer even when they would rather not.

However, if a respondent refuses to answer or continue, then this must be respected.

In Chapter 4 we examined the pros and cons of including ‘Not answered/refused’ codes at every question and concluded that they should not necessarily be included as a matter of course. However, it should be possible to identify the questions that are most likely to be refused and to include a code for refusals as appropriate. Such questions are likely to be the sensitive questions listed above, and personal questions such as income and questions about family relationships.

With paper questionnaires the interview can progress even if a question is not answered, unless an answer is required for routeing purposes.

In Chapter 9 the issue of electronic self-completion questionnaires was discussed and whether or not the researcher should build in an ability to move on to the next question following a refusal to answer. The alternative to allowing this can be that the respondent terminates the interview rather than answer the question. Different research organizations take different views on whether to accept termination of the interview or to provide another mechanism that allows respondents not to answer.

5.2. Maintaining interest

It could be considered an ethical issue that respondents must not be put through a process that is boring and tedious.

The ethics of, for example, a telephone survey questionnaire that consists almost entirely of 200 rating scales that would take most people nearly an hour to answer, and on a topic that is of low interest to most respondents, must be questioned. This may be an extreme (although true) example, but questionnaire writers must look out for any tendency towards this.

Creating a boring interview is not just bad questionnaire design, which leads to unreliable data. It is also ethically questionable, fails to treat the respondents with respect, and damages the reputation of market research.

Long and repetitive interviews should be avoided. This sometimes means that the questionnaire writer must find a creative way of asking what would otherwise be repetitive questions. Batteries of rating scales, in particular, can cause problems because of the desire to maintain a common format for analysis purposes.

Source: Brace Ian (2018), Questionnaire Design: How to Plan, Structure and Write Survey Material for Effective Market Research, Kogan Page; 4th edition.

20 Aug 2021

20 Aug 2021

20 Aug 2021

20 Aug 2021

20 Aug 2021

20 Aug 2021