Assessment of general locations and the specific sites within them requires extensive analysis. In any area, the optimum site for a particular store is called the one-hundred percent location. Because different retailers need different kinds of sites, a location labeled as 100 percent for one firm may be less desirable for another. An upscale ladies’ apparel shop would seek a location unlike one sought by a convenience store. The apparel shop would benefit from pedestrian traffic, closeness to major department stores, and proximity to other specialty stores. The convenience store would rather be in an area with ample parking and vehicular traffic. It does not need to be near other stores.

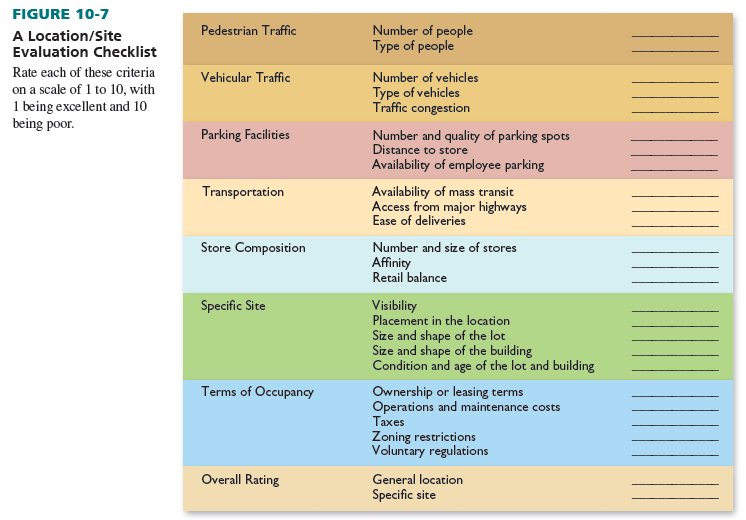

Figure 10-7 has a location/site evaluation checklist. A retailer should rate each alternative location (and specific site) on all the criteria and develop overall ratings for them. Two firms may rate the same site differently. This figure should be used in conjunction with the trading-area data in Chapter 9, not instead of them.

1. Pedestrian Traffic

The most crucial measures of a location’s and site’s value are the number and type of people passing by. Other things being equal, a site with the most pedestrian traffic is often best.

Not everyone passing a location or site is a good prospect for all types of stores, so many firms use selective counting procedures, such as counting only those with shopping bags. Otherwise, pedestrian traffic totals may include many nonshoppers. It would be improper for an appliance retailer to count as prospective shoppers all people passing a downtown site on the way to work. Much downtown pedestrian traffic may be from those who are there for nonretailing activities.

A proper pedestrian traffic count should encompass these four elements:

- Separation of the count by age and gender (with very young children not counted).

- Division of the count by time (this allows the study of peaks, low points, and changes in the gender of the people passing by the hour).

- Pedestrian interviews (to find out the proportion of potential shoppers).

- Spot analysis of shopping trips (to verify the stores actually visited).

2. Vehicular Traffic

The quantity and characteristics of vehicular traffic are very important for retailers that appeal to customers who drive there. Convenience stores, outlets in regional shopping centers, and car washes are retailers that rely on heavy vehicular traffic. Automotive traffic studies are essential in suburban areas, where pedestrian traffic is often limited.

As with pedestrian traffic, adjustments to the raw count of vehicular traffic must be made. Some retailers count only homeward-bound traffic, some exclude vehicles on the other side of a divided highway, and some omit out-of-state cars. Data may be available from the state highway department, the county engineer, or the regional planning commission.

Besides traffic counts, the retailer should study the extent and timing of congestion (from traffic, detours, and poor roads). People normally avoid congested areas and shop where driving time and driving difficulties are minimized.

3. Parking Facilities

Many U.S. retail stores include some provision for nearby off-street parking. In many business districts, parking is provided by individual stores, arrangements among stores, and local government. In planned shopping centers, parking is shared by all stores there. The number and quality of parking spots, their distances from stores, and the availability of employee parking should all be evaluated. See Figure 10-8.

The need for retailer parking facilities depends on the store’s trading area, the type of store, the proportion of shoppers using a car, the existence of other parking, the turnover of spaces (which depend on the length of a shopping trip), the flow of shoppers, and parking by nonshoppers. A shopping center normally needs 4 to 5 parking spaces per 1,000 square feet of gross floor area, a supermarket 10 to 15 spaces, and a furniture store 3 or 4 spaces.

Free parking sometimes creates problems. Commuters and employees of nearby businesses may park in spaces intended for shoppers. This problem can be lessened by validating shoppers’ parking stubs and requiring payment from nonshoppers. Another problem may occur if the selling space at a location increases due to new stores or the expansion of current ones. Existing parking may then be inadequate. Double-deck parking or parking tiers save land and shorten the distance from a parked car to a store—a key factor because customers at a regional shopping center may be unwilling to walk more than a few hundred feet from their cars to the center.

4. Transportation

Mass transit, access from major highways, and ease of deliveries must be examined. For example, in a downtown area, closeness to mass transit is important for people who do not own cars, who commute to work, or who would not otherwise shop in an area with traffic congestion. The availability of buses, taxis, subways, trains, and other kinds of public transit is a must for any area not readily accessible by vehicular traffic.

Locations dependent on vehicular traffic should be rated on nearness to major thoroughfares. Driving time is a consideration for many people. Also, drivers heading eastbound on a highway often do not like to make a U-turn to get to a store on the westbound side of that highway.

The transportation network should be studied for delivery truck access. Some thoroughfares are excellent for cars but ban large trucks or cannot bear their weight.

5. Store Composition

The number and size of stores should be consistent with the type of location. A retailer in an isolated site wants no stores nearby; a retailer in a neighborhood business district wants an area with 10 to 15 small stores; and a retailer in a regional shopping center wants a location with many stores, including large department stores (to generate customer traffic).

If the stores at a given location (be it an unplanned district or a planned center) complement, blend, and cooperate with one another, and each benefits from the others’ presence, affinity exists. When affinity is strong, the sales of each store are greater, due to the high customer traffic, than if the stores are apart. The practice of similar or complementary stores locating near each other is based on two factors: First, customers like to compare the prices, styles, selections, and services of similar stores. Second, customers like one-stop shopping and like to purchase at different stores on the same trip. Affinities can exist among competing stores as well as among complementary stores. More people travel to shopping areas with large selections than to convenience-oriented areas, so the sales of all stores are enhanced.

One measure of compatibility is the degree to which stores exchange customers. Stores in these categories are very compatible with each other and have high customer interchange:

- Supermarket, drugstore, bakery, fruit-and-vegetable store, meat store

- Department store, apparel store, hosiery store, lingerie shop, shoe store, jewelry store

Retail balance, the mix of stores within a district or shopping center, should also be considered. (1) Proper balance occurs when the number of store facilities for each merchandise or service classification is equal to the location’s market potential, (2) a range of goods and services is provided to foster one-stop shopping, (3) there is an adequate assortment within any category, and (4) there is a proper mix of store types (balanced tenancy).

6. Specific Site

Selecting the specific site for the retail store depends on visibility; placement in the location, size, and shape of the lot; size and shape of the building; and condition and age of the lot and building.

Visibility is a site’s ability to be seen by pedestrian or vehicular traffic. A site on a side street or at the end of a shopping center is not as visible as one on a major road or at the center’s entrance. High visibility increases store awareness.

Placement in the location is a site’s relative position in the district or center. A corner location may be desirable because it is situated at the intersection of two streets and has “corner influence.” It is usually more expensive because of the greater pedestrian and vehicular passersby due to traffic flows from two streets, increased window display area, and less traffic congestion through multiple entrances. Corner influence is greatest in high-volume locations. That is why some Pier 1 stores, Starbucks restaurants, and other retailers seek corner sites. See Figure 10-9.

A convenience-oriented firm, such as a stationery store, is very concerned about the side of the street, the location relative to other convenience-oriented stores, nearness to parking, access to a bus stop, and the distance from residences. A shopping-oriented retailer, such as a furniture store, is more interested in a corner site to increase window display space, proximity to wallpaper and other related retailers, the accessibility of its pick-up platform to consumers, and the ease of deliveries to the store.

When a retailer buys or rents an existing building, its size and shape should be noted. Condition and age of the lot and the building should be studied, as well. A department store, of course, requires much more space than a boutique. It may desire a square site, whereas the boutique might prefer a rectangular one. Any site should be viewed in terms of total space needs: parking, walkways, selling, nonselling, and so on.

Due to the saturation of many desirable locations and the lack of available spots in others, some firms have turned to nontraditional sites—often to complement their existing stores. T.G.I. Friday’s, Staples, and Bally have airport stores. Subway has outlets in many Walmarts, and Subway and some other fast-food retailers share facilities to provide more variety and to share costs.

7. Terms of Occupancy

Terms of occupancy—ownership versus leasing, type of lease, operations and maintenance costs, taxes, zoning restrictions, and voluntary regulations—must be evaluated for each prospective site.

OWNERSHIP VERSUS LEASING A retailer with adequate funding can either own or lease premises. Ownership is more common in small stores, in small communities, or at inexpensive locations. It has several advantages. There is no chance that a property owner will not renew a lease or double the rent when a lease expires. Monthly mortgage payments are stable. Operations are flexible; a retailer can engage in scrambled merchandising and break down walls. It is also likely that property value will appreciate over time, resulting in a financial gain if the business is sold. Ownership disadvantages are high initial costs, long-term commitment, and inability to readily change sites. Home Depot owns about 90 percent of its store properties.18

If a retailer chooses ownership, the next decision is whether to construct a new facility or buy an existing building. Considerations include purchase price and maintenance costs, zoning restrictions, age and condition of existing facilities, adaptability of existing facilities, and time to erect a new building. To encourage building rehabilitation in towns with 5,000 to 50,000 people, Congress enacted the Main Street America program (www.mainstreet.org) of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. It has a network of statewide, citywide, and regional programs actively serving more than 2,000 towns, which benefit from planning support, tax credits, and low-interest loans.

The great majority of stores in central business districts and regional shopping centers are leased (with Home Depot sometimes being one of the exceptions), mostly due to the high investment for ownership. Department stores tend to have renewable 20- to 30-year leases, supermarkets usually have renewable 15- to 20-year leases, and specialty stores often have 5- to 10-year leases with options to extend. Some leases give the retailer the right to end an agreement before the expiration date—under given circumstances and for a specified retailer payment.

Leasing minimizes initial investment, reduces risk, provides access to prime sites that cannot add more stores, leads to immediate occupancy and traffic, and reduces long-term commitment. Many retailers feel they can open more stores or spend more on their strategies by leasing. Firms that lease accept limits on operating flexibility, restrictions on subletting and selling the business, possible nonrenewal problems, rent increases, and not gaining from rising real-estate values.

Through a sale-leaseback, some large retailers build stores and then sell them to real-estate investors who lease the property back to the retailers on a long-term basis. Retailers using sale-leasebacks build stores to their specifications and have bargaining power in leasing—while lowering capital expenditures.

TYPES OF LEASES Property owners do not rely solely on constant rent leases, partly due to their concern about interest rates and the related rise in operating costs. Terms can be quite complicated.19

The simplest, most direct arrangement is the straight lease—a retailer pays a fixed dollar amount per month over the life of the lease. Rent usually ranges from $1 to $75 annually per square foot, depending on the site’s desirability and store traffic. At some sites, rents can be much higher. On New York’s Fifth Avenue, the average yearly rental rate ranges up to $3,500 per square foot! This is the world’s highest retail rental rate.20

A percentage lease stipulates that rent is related to sales or profits. This differs from a straight lease, which requires constant payments. A percentage lease protects a property owner against inflation and lets it benefit if a store is successful; it also allows a tenant to view the lease as a variable cost—rent is lower when its performance is weak and higher when performance is good. The percentage rate varies by type of shopping district or center and by type of store.

Percentage leases have variations. With a specified minimum, low sales are assumed to be partly the retailer’s responsibility; the property owner receives minimum payments (as in a straight lease) no matter what the sales or profits. With a specified maximum, it is assumed that a very successful retailer should not pay more than a maximum rent. Superior merchandising, promotion, and pricing should reward the retailer. Another variation is a sliding scale: The ratio of rent to sales changes as sales rise. A sliding-down scale has a retailer pay a lower percentage as sales go up and is an incentive to the retailer.

A graduated lease calls for precise rent increases over a stated period of time. Monthly rent may be $4,800 for the first 10 years and $5,600 for the last 10 years of a lease. Rent is known in advance by the retailer and the property owner; it is based on expected sales and cost increases. There is no need to audit sales or profits, as with percentage leases. This lease is often used with small retailers.

A maintenance-increase-recoupment lease has a provision allowing rent to increase if a property owner’s taxes, heating bills, insurance, or other expenses rise beyond a certain point. This provision most often supplements a straight rental lease agreement.

A net lease calls for all maintenance costs (such as heating, electricity, insurance, and interior repair) to be paid by the retailer. It frees the property owner from managing the facility and gives the retailer control over store maintenance. It supplements a straight lease or a percentage lease.

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS After assessing ownership and leasing opportunities, a retailer must look at the costs of operations and maintenance. The age and condition of a facility may cause a retailer to have high monthly costs, even though the mortgage or rent is low. Furthermore, the costs of extensive renovations should be calculated.

Differences in sales taxes (those that customers pay) and business taxes (those that retailers pay) among alternative sites must be weighed. Business taxes should be broken down into real- estate and income categories. The highest statewide sales taxes are in California (7.5 percent) and in Indiana, Mississippi, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and Tennessee (7 percent); Alaska, Delaware, Montana, New Hampshire, and Oregon have no state sales tax.

There may be zoning restrictions as to the kind of stores allowed, store size, building height, type of merchandise carried, and other factors that have to be hurdled (or another site chosen). For example, many communities believe their local retail economies can handle only so many new stores without causing some existing firms to fail. Thus, they have passed zoning regulations or store size caps that forbid retail stores from exceeding a given size. This helps local communities sustain the vitality of small, pedestrian-oriented business districts, keep commercial retail space affordable, and nurture local retailers. Size caps can prevent traffic congestion and overburdened public infrastructure. They require all retailers, including retail chains such as Walmart, to build stores that are properly sized for the community. Cities that have adopted size caps find that, in some cases, retailers that typically build larger stores will opt not to open; in other cases, they will design smaller stores. Size caps also ensure that retail space is affordable for local business. 21

Voluntary restrictions are prevalent in planned shopping centers and may include required membership in merchant groups, uniform hours, and shared security forces. Leases in regional centers have had clauses protecting anchor tenants from too much competition from discounters. Clauses may also involve limits on product lines, fees for common services, and so on. Anchors are protected because developers need long-term commitments to finance the centers. The Federal Trade Commission discourages “exclusives,” whereby only a certain retailer can carry specified merchandise, and “radius clauses,” whereby a tenant agrees not to have another store within a certain distance.

Because of overbuilding, some retailers are in a good position to bargain over the terms of occupancy. This differs from city to city and from shopping location to shopping location.

8. Overall Rating

The last task in choosing a store location is to compute overall ratings:

- Each location under consideration is given an overall rating based on the criteria in Figure 10-7.

- The overall ratings of alternative locations are compared, and the best location is chosen.

- The same procedure is used to evaluate the alternative sites within the location.

It is often difficult to compile and compare composite evaluations because some attributes may be positive whereas others are negative. The general location may be a good shopping center, but the site in the center may be poor, or an area may have excellent potential but it takes 2 years to build a store. The attributes in Figure 10-7 should be weighted according to their importance. An overall rating should also include knockout factors—those that preclude consideration of a site. Possible knockout factors are a short lease, little or no evening or weekend pedestrian traffic, and poor tenant relations with the landlord.

Source: Barry Berman, Joel R Evans, Patrali Chatterjee (2017), Retail Management: A Strategic Approach, Pearson; 13th edition.

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyways, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking back frequently!