In Chapter 1, we introduced the concept of relationship retailing, whereby retailers seek to form and maintain long-term bonds with customers, rather than act as if each sales transaction is a new encounter with them. For relationship retailing to work, enduring value-driven relationships are needed with other channel members, as well as with customers. Both jobs are challenging. See Figure 2-3. Visit our blog for posts related to relationship retailing issues (www.bermanevansretail .com).

1. Customer Relationships

Loyal customers are the backbone of a business. Thus, it is important that retailers retain their loyal customers through repeated sales in a trusting relationship. Loyalty has two unique dimensions— attitudinal and behavioral—and each contributes differently to retailers’ revenues, profits, and market share.8 Customers who are attitudinally loyal will have a higher tendency to spread positive word-of-mouth recommendations to friends and family on social media, have a higher commitment to the retailer, and not be reluctant to pay more for products at a particular retailer.

Customers who are behaviorally loyal will have a higher tendency to continue purchasing from a particular retailer. Behavioral loyalty may also be a manifestation of inertia (or inertial loyalty) due to high switching costs associated with changing retailers. Although both attitudinal and behavioral loyalty are important to achieve business goals and to sustain the position in the marketplace, a retailer’s positioning strategy (discussed in Chapter 3) will influence which dimension needs to be strategically managed. Attitudinal loyalty should be emphasized if the objective is to charge higher prices, whereas behavioral loyalty should be more important if the objective is to increase market share or profits.9

In a competitive industry such as retailing, many consumers show divided behavioral loyalty to more than one retailer for a single category need. Here’s why: You have satisfied customers. “That’s good, right? Well, yes for the short term the customer[s] will continue purchasing. While a loyal customer is a satisfied customer, the converse is not necessarily true. Real loyalty [or attitudinal loyalty]—much harder to earn than mere satisfaction—tells you that your customer wants to stick with you over the long haul and will share that feeling with others.”10 Retailers need to develop and strategically manage loyalty programs to cultivate behavioral loyalty (discussed later in this chapter). But in the long term, it’s not necessarily enough. Customers who spend a lot can defect to the retailer providing lower prices or better service and enroll in multiple loyalty programs. Attitudinal loyalty derives not from hum-drum “good” transactions but from exceeding customer expectations on a repeated basis and delightful experiences that make shoppers so emotionally devoted that they want to share their experience by telling others.

In relationship retailing, there are four factors to keep in mind: the customer base, customer service, customer satisfaction, and loyalty programs and defection rates. Let’s explore these next.

THE CUSTOMER BASE Retailers must regularly analyze their customer base in terms of population and lifestyle trends, attitudes toward and reasons for shopping, the level of loyalty, and the mix of new versus loyal customers.

As reported by the Census Bureau, the U.S. population is aging. One-fourth of households consist of only one person, one-seventh of people move annually, most people live in urban and suburban areas, middle-class income has been rising very slowly, and African American, Hispanic American, and Asian American segments are expanding. Thus, gender roles are changing, shoppers demand more, consumers are more diverse, there is less interest in shopping, and time-saving goods and services are desired.

Future retail trends will be driven by the Millennials (Generation Y), who have surpassed Baby Boomers as the largest generation. According to the Pew Research Center, there are about 75 million Americans born between the early 1980s and the late 1990s; and they defy easy categorization, for they are the most racially diverse generation the United States has experienced.11 Millennials have an elevated sense of idealism and are concerned how brands and retailers perform on social responsibility, sustainability, gender equality, and fair trade.

In their quest for growth in market share and sales revenue, many retailers typically focus on one side of customer value—delivering value. The customer is king (or queen) and everything must be done to deliver superior value and to delight him (or her). Astute retailers balance this view with the other side of customer value—receiving value. This is achieved by attracting and retaining those customers who provide value in the form of profits to the firm through their transactions.

It is worth more to nurture relationships with some shoppers than with others. These are the retailer’s core customers—its best customers—loyal, satisfied customers who get high value from the retailer and generate high profits for the retailer. These core customers are the most desirable, are resistant to competitors’ enticements of better deals, and deliver long-term profits. At the other extreme are the “lost causes” who don’t value the retailer’s goods or services and are not profitable.12 They cost the retailer more than they are worth because they frequently complain and return products, spread bad word of mouth, misuse promotions, and lower staff morale through their interactions. It does not make economic sense for the retailer to acquire them in the first place. Losing these customers may reduce market share but lead to improved profitability and higher levels of retailer performance. “Free-riders” (customers who are highly satisfied with the company but not highly profitable) and vulnerable customers (profitable but not satisfied with the retailer) can be managed through customer relationship management strategies. Charging higher prices and reducing services for free-riders can increase profitability. It is important for retailers to identify unmet needs of vulnerable customers and consider whether it will be profitable to satisfy them; otherwise, competitors will poach them away.

Retailers need to identify their best customers and see what characteristics differentiate these profitable customers from all the rest. Next, the retailer should determine whether it makes economic sense to pursue a differentiated offering to free-riders and vulnerable customers and to fine-tune strategies for the consumers who are most likely to yield profitable customers.

A retailer’s desired mix of new versus loyal customers depends on that firm’s stage in its life cycle, goals, and resources, as well as competitors’ actions. A mature firm is more apt to rely on core customers and supplement its revenues with new shoppers. A new firm faces the dual tasks of attracting shoppers and building a loyal following; it cannot do the latter without the former. If goals are growth-oriented, the customer base must be expanded by adding stores, increasing advertising, and so on; the challenge is to do this in a way that does not deflect attention from core customers. Although it is more costly to attract new customers than to serve existing ones, core customers are not cost-free; they must be service properly. If competitors try to take away a retailer’s existing customers with price cuts and special promotions, that retailer might pursue the competitors’ customers in the same way. Again, regardless of what action is taken, all retailers must be careful not to alienate core customers.

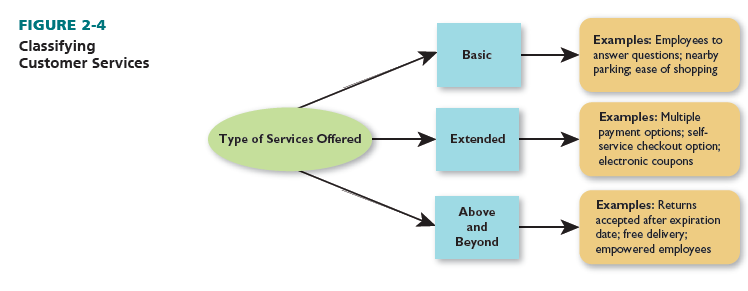

CUSTOMER SERVICE As described in Chapter 1, customer service refers to the identifiable, but sometimes intangible, activities undertaken by a retailer in conjunction with the goods and services it sells. It has an impact on the total retail experience. Consistent with a value chain philosophy, retailers must apply two elements of customer service. Expected customer service is the service level that customers want to receive from any retailer, such as basic employee courtesy. Augmented customer service includes the activities that enhance the shopping experience and give retailers a competitive advantage.

The attributes of personnel who interact with customers (such as politeness and knowledge), as well as the number and variety of customer services offered, have a strong effect on the relationship created. Although planning a superior customer service strategy can be complex, a well- executed strategy can pay off in a big way.

Some retailers realize customer service is better if they utilize employee empowerment, whereby workers have the discretion to do what they believe is necessary—within reason—to satisfy the customer, even if this means bending the rules. The founders of Home Depot made a strategic decision to train employees to form enduring customer relationships rather than push for incremental sales gains. As a result, the retailer grew very quickly because of its outstanding customer service. Home Depot’s core value, “Taking care of our people,” states that the company encourages associates to speak up and take risks, recognizes and rewards good work performance, and leads and develops employees so that they may grow. Home Depot believes that the key to its success and its competitive advantage in the marketplace is treating people well—starting with employees, who in turn ensure that customers are treated well. However, Home Depot’s American Customer Satisfaction Index rating tumbled to the bottom in the home-improvement category when it faced a high- profile credit-card security breach in the fall of 2014.13 That rating has risen since then.

To apply customer service effectively, a firm must first develop an overall service strategy and then plan individual services. Figure 2-4 shows one way a retailer may view the customer services it offers.

DEVELOPING A CUSTOMER SERVICE STRATEGY. A retailer must make the following vital decisions.

What customer services are expected and what customer services are augmented for a particular retailer? Examples of expected customer services are credit for a furniture retailer, new-car preparation for an auto dealer, and a liberal return policy for a gift shop. Those retailers could not stay in business without these services. Because augmented customer services are extra elements, a firm could serve its target market without such services, but using them will enhance its competitive standing. Examples are home delivery for a supermarket within a 1-hour window, an extended warranty for a used auto dealer, and free gift wrapping for a toy store. Each firm needs to learn which customer services are expected and which are augmented for its situation. Services that are viewed as expected customer services for one retailer, such as delivery, may be viewed as augmented for another. See Figure 2-5.

What level of customer service is proper to complement a firm’s image? An upscale retailer would offer more customer services than a discounter because people expect the upscale firm to have a wider range of customer services as part of its basic strategy. Performance would also be different. Customers of an upscale retailer may expect elaborate gift wrapping, valet parking, an in-store restaurant, and a ladies’ room attendant, whereas discount shoppers may expect cardboard gift boxes, self-service parking, a lunch counter, and an unattended ladies’ room. Customer service categories are the same; performance is not.

Should there be a choice of customer services? Some firms let customers select from various levels of customer service; others provide only one level. A retailer may honor several credit cards or only its own. Trade-ins may be allowed on some items or all. Warranties may have optional extensions or fixed lengths. A firm may offer 1-, 3-, and 6-month payment plans or insist on immediate payment.

Should customer services be free? Two factors cause retailers to charge for some customer services: First, delivery, gift wrapping, and some other customer services are labor intensive, and second, people are more apt to be home for a delivery or service call if a fee is imposed. Without a fee, a retailer may have to attempt a delivery twice. In settling on a free or fee-based strategy, a firm should (1) determine which customer services are expected (these are often free) and which are augmented (these may be offered for a fee); (2) monitor competitors and profit margins; and (3) study the target market. In setting fees, a retailer must also decide if its goal is to break even or to make a profit on certain customer services.

How can a retailer measure the benefits of providing customer services against the cost of the services? The aim of customer services is to enhance the shopping experience in a way that attracts and retains shoppers—while maximizing sales and profits. Thus, augmented services should not be offered unless they increase total sales and profits. A retailer should plan augmented customer services based on its experience, competitors’ actions, and customer comments; when the costs of providing these customer services increase, higher prices should be passed on to the consumers.

How can customer services be terminated? When a customer service strategy is set, shoppers are apt to react negatively to any customer service reduction. Yet, some costly augmented customer services may have to be dropped. In that case, the best approach is to be forthright by explaining why the customer services are being terminated and how customers will benefit via lower prices. Sometimes a firm may use a middle ground, charging for previously free customer services (such as clothing alterations) to allow those who want the services to still receive them.

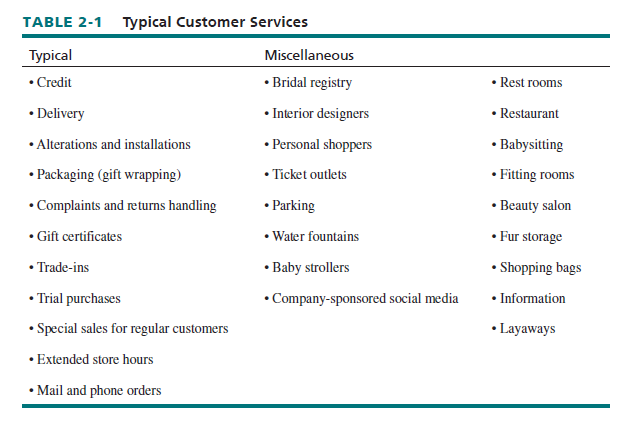

PLANNING INDIVIDUAL CUSTOMER SERVICES. After a broad customer service plan is outlined, individual customer services need to be planned. A department store may offer credit, layaway, gift wrapping, a bridal registry, free parking, a restaurant, a beauty salon, carpet installation, dressing rooms, clothing alterations, restrooms and sitting areas, the use of baby strollers, home delivery, and fur storage. See Table 2-1 for a range of typical customer services.

Most retailers let customers make credit purchases; and many firms accept personal checks with proper identification. Consumers’ use of credit rises as the purchase amount goes up. Retailer- sponsored credit cards have three key advantages: (1) The retailer saves the fee it would pay for outside card sales, (2) people are encouraged to shop with a given retailer because its card is usually not accepted elsewhere, and (3) contact can be maintained with customers and information learned about them. There are also disadvantages to retailer cards: Startup costs are high, the firm must worry about unpaid bills and slow cash flow, credit checks and follow-up tasks must be performed, and customers without the firm’s card may be discouraged from shopping at that particular retail store. Bank and other commercial credit cards enable small and medium retailers to offer credit, generate added business for all types of retailers, appeal to mobile shoppers, provide advertising support from the sponsor, reduce bad debts, eliminate startup costs for the retailer, and provide data. Yet, the cards charge a transaction fee and do not yield loyalty to a retailer.

Most bank cards and retailer cards involve a revolving credit account, whereby a customer charges items and is billed monthly on the basis of the outstanding cumulative balance. An option credit account is a form of revolving account; no interest is assessed if a person pays a bill in full when it is due. When a person makes a partial payment, he or she is assessed interest monthly on the unpaid balance. Some credit card firms (such as American Express) and some retailers offer an open credit account, whereby a consumer must pay the bill in full when it is due. Partial, revolving payments are not permitted. A person with an open account also has a credit limit (although it may be more flexible).

For a retailer that offers delivery, there are three decisions: the transportation method, equipment ownership versus rental, and timing. The transportation method can be car, van, truck, rail, mail, and so forth. The costs and appropriateness of the methods depend on the products. Regarding transportation equipment ownership, large retailers often find it economical to own their delivery vehicles. This also lets them advertise the company name, have control over schedules, and use their employees for deliveries. Small retailers serving limited trading areas may use personal vehicles. Many small, medium, and even large retailers use shippers such as UPS if consumers live away from a delivery area and shipments are not otherwise efficient. And finally, for the timing of delivery, the retailer must decide how quickly to process orders and how often to deliver to different locales.

For some firms, alterations and installations are expected services—although more retailers now charge fees. However, many discounters have stopped offering alterations of clothing and installations of appliances on both a free and a fee basis. They feel the services are too ancillary to their business and not worth the effort. Other retailers offer only basic alterations: shortening pants, taking in the waist, and lengthening jacket sleeves. They do not adjust jacket shoulders or width. Some appliance retailers may hook up washing machines but not do plumbing work.

Within a store, packaging (gift wrapping)—as well as complaints and returns handling—can be centrally located or decentralized. Centralized packaging counters and complaints and returns areas have advantages: They may be located in otherwise dead spaces, the main selling areas are not cluttered, specialized personnel can be used, and there is a common policy. The advantages of decentralization are that shoppers are not inconvenienced, they are kept in the selling area (where a salesperson may resolve a problem or offer different merchandise), and extra personnel are not required. In either case, clear guidelines as to the handling of complaints and returns are needed.

Gift cards encourage shopping with a given retailer. Many firms require gift cards to be spent and not redeemed for cash. Trade-ins also induce new and regular shoppers to visit the store or its Web site. People may feel they are getting a bargain. Trial purchases let shoppers test products before purchases are final.

Retailers increasingly offer special customer services to their regular customers. Sales events (not open to the general public) and extended hours are provided. Mail and phone orders are handled for convenience.

Other useful customer services include a bridal registry, interior designers, personal shoppers, ticket outlets, free (or low-cost) and plentiful parking, water fountains, pay phones, baby strollers, company-sponsored social media, restrooms, a restaurant, babysitting, fitting rooms, a beauty salon, fur storage, shopping bags, information counters, and layaway plans.

A retailer’s willingness to offer some or all of these services indicates to customers a concern for them. Therefore, firms need to consider the impact of excessive self-service. Research shows that some shoppers think self-service technologies (SSTs) are used by service providers to cut costs rather than extend customer service. Thus, service managers need to provide a clear reason for using SSTs to stimulate customers’ attribution of higher benefits and convenience.14

CUSTOMER SATISFACTION Customer satisfaction occurs when the value and customer service provided through a retailing experience meet or exceed consumer expectations. If the expectations of value and customer service are not met, the consumer will be dissatisfied. “Retail satisfaction consists of three categories: shopping systems satisfaction, which includes availability and types of outlets; buying systems satisfaction, which includes selection and actual purchasing of products; and consumer satisfaction, which is derived from the use of the product. Dissatisfaction with any of the three aspects could lead to customer disloyalty, decrease in sales, and erosion of the market share.”15

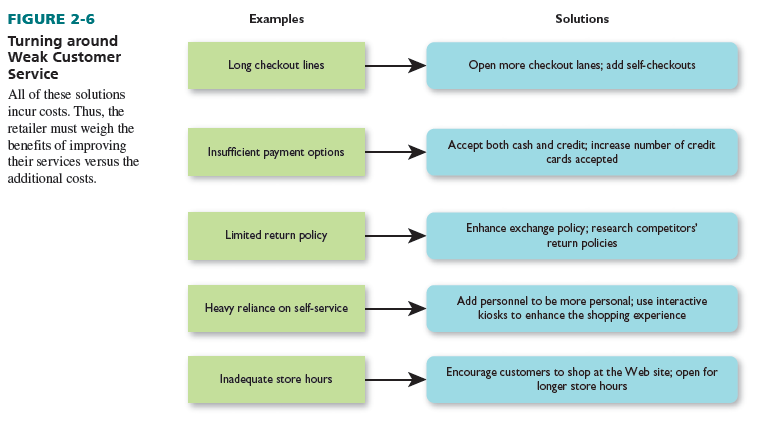

Only “very satisfied” customers are likely to remain loyal in the long run. How well are retailers doing in customer satisfaction? Many have much work to do. The American Customer Satisfaction Index (www.theacsi.org) annually questions thousands of people to link customer expectations, perceived quality, and perceived value to satisfaction. Overall, department and discount stores generally have scores from 66 to 82, supermarkets from 67 to 86, and specialty retail stores from 65 to 81 (on a scale of 100). Gasoline stations usually rate lowest in the retailing category (with scores around 70). To improve matters, retailers should consider engaging in the activities shown in Figure 2-6.

Most consumers do not complain to the retailer when dissatisfied; they just shop elsewhere. Why don’t shoppers complain more? (1) Most people feel complaining produces little or no positive results, so they do not bother to complain, and (2) complaining is not easy. Consumers have to find the party to whom they should complain, access to that party may be restricted, and written forms may have to be completed.

To obtain more feedback, retailers must make it easier for shoppers to complain, make sure shoppers believe their concerns are addressed, and sponsor ongoing customer satisfaction surveys. As suggested by software firm StatPac, retailers should ask such questions as these and then take corrective actions:

- “Overall, how satisfied or dissatisfied are you with the store?”

- “How satisfied or dissatisfied are you with the price of the items you purchased?”

- “How satisfied or dissatisfied are you with the quality of the merchandise?”

- “Please tell us something we could do to improve our store.”16

LOYALTY PROGRAMS AND DEFECTION RATES Consumer loyalty (frequent shopper) programs reward a retailer’s best customers, those with whom it wants long-lasting relationships. These programs have been shown to enhance consumers’ purchase frequencies and volumes. An example of a loyalty program is after your membership card is punched nine times, indicating that you’ve had nine pancake breakfasts, your tenth pancake breakfast is free. Loyalty programs vary dramatically, based on number of visits, reward timing, reward type, reward value, behavior before and after redemptions, accumulation of credits toward the award, the behavioral unit used to track purchase behavior (e.g., points, miles flown, nights stayed, dollars, number of purchases/visits, etc.), the redemption policy of rewards, and the reward program enrollment fee. Academic research shows that consumers who pay a fee to participate in loyalty programs have more favorable attitudes toward the programs and higher behavioral loyalty, focus more on the benefits associated with program enrollment, and perceive the programs as a better value than consumers who enroll in a loyalty program for free.17

For retailers, fee-based programs increase consumer revenue after enrollment (in addition to the revenue generated from the fee). In general, the higher the program fee, the lower the consumers’ willingness to join. When membership fees are nominal (or free), simple dollar and point accrual work best, as these programs lead to the highest joining intentions and keep the consumer focused on cost/benefit assessments of the program (rather than the price of the program).18 Simple accrual systems allow for easy conversions and should make the ultimate reward seem closer to obtaining and more attractive, enhancing the cost/benefit ratio for customers. Retailers who offer higher fee-based loyalty programs are more likely to attract members when they offer complex accruals—the accrual of multiple points per dollar spent to encourage consumers to consider the benefits of reward membership holistically.

Retailers in categories with less differentiation (e.g., airlines and supermarkets) offer loyalty programs with the goal of increasing repeat business and profitability. In these cases, a decision to join a loyalty program may have a big impact by increasing customer perceptions of switching costs that increase behavioral loyalty. Firms can collect customer contact and socio-demographic information when they sign up, and track browsing and purchase behavior that they can use to personalize offers and strengthen the exchange with customers.19

From the shopper’s perspective, there are five types of reward categories:20

- Economic rewards include price reductions and purchase vouchers. These rewards attract price-sensitive customers and induce them to buy more. Dunkin Donuts DDPerks program members receive a free beverage after earning 200 Points ($40 in spending) on qualifying

Members receive promotional E-mails with dollars off selected food or beverage items automatically applied when they use the mobile app or loyalty card in stores.21 - Hedonistic rewards include things such as points that can be exchanged for spa services or participation in games or sweepstakes. These rewards have more emotional value and will attract people who shop for pleasure.

- Social-relational rewards include things such as mailings about special events or the right to use special waiting areas at airports. Consumers who want to be identified with a privileged group will value these kinds of rewards.

- Informational rewards include things such as personalized beauty advice or information on new goods or services. These rewards will attract consumers who like to stick with one brand or store.

- Functional rewards include things such as access to priority checkout counters or home delivery. Consumers who want to reduce the time they spend shopping will value these most. Dunkin Donuts DDperks rewards members can use the On-The-Go mobile app to order ahead and skip the line at the store.

What do good customer loyalty programs have in common? Their rewards are useful and appealing, and they are attainable in a reasonable time. Referrals (through social media or direct invites) are rewarded, as well as frequent shopping behavior (the greater the purchases, the greater the benefits). Each year, Starbucks Rewards members start at the Green Level and earn two stars for each $1 spent until they accumulate 300 stars for Gold status. The latter members earn free beverages for every 125 stars and other benefits until the end of the year.22 Rewards that are unique to particular retailers and not redeemable elsewhere are more effective. Rewards stimulate both short- and long-run purchases. Customer communications are personalized. Frequent shoppers feel “special.” Participation rules are publicized and rarely change.

When a retailer studies customer defections (by tracking databases or surveying consumers), it can learn how many customers it is losing and why they no longer patronize a firm. Customer defections may be viewed in absolute terms (people who no longer buy from the firm at all) and in relative terms (people who shop less often or who have reduced their average purchase quantity). Each retailer must define its acceptable defection rate. Furthermore, not all shoppers are “good” customers. A retailer may feel it is okay if shoppers who always look for sales, return items without receipts, and expect fee-based services to be free decide to defect. Unfortunately, too few retailers review defection data or survey defecting customers because of the complexity of doing so and an unwillingness to hear “bad news.”

2. Channel Relationships

Within a value chain, the members of a distribution channel (manufacturers, wholesalers, and retailers) jointly represent a value delivery system, which comprises all the parties that develop, produce, deliver, and sell and service particular goods and services. These are the ramifications for retailers:

- Each channel member is dependent on the others. When consumers shop with a certain retailer, they often do so because of the retailer as well as the products it carries.

- All activities in a value delivery system must be enumerated and responsibility assigned.

- Small retailers may have to use suppliers outside the normal distribution channel to get items they want and gain adequate supplier support. Large firms may be able to buy directly from manufacturers; smaller firms may have to buy through wholesalers handling such accounts.

- A value delivery system is as good as its weakest link. No matter how well a retailer performs its activities, it will still have unhappy shoppers if suppliers deliver late or do not honor warranties.

- The nature of a given value delivery system must be related to target market expectations.

- Channel member costs and functions are influenced by each party’s role. Long-term cooperation and two-way information flows foster efficiency.

- Value delivery systems are complex due to the vast product assortment of superstores, the many forms of retailing, and the use of multiple distribution channels by some manufacturers.

- Nonstore retailing (such as mail order, phone, and Web transactions) requires a different delivery system than store retailing.

- Due to conflicting goals about profit margins, shelf space, and so on, some channel members are adversarial—to the detriment of the value delivery system and channel relationships.

When they forge strong positive channel relationships, members of a value delivery system better serve each other and the final consumer. Here’s how: Walmart and Sam’s Club work closely with suppliers to drive out unnecessary costs in order to pass savings to their shoppers.23

Ace Hardware’s cooperative structure allows its buyers to negotiate with the power of over 4,800 locations, so that store owners have a significant advantage over nonaffiliated stores.24

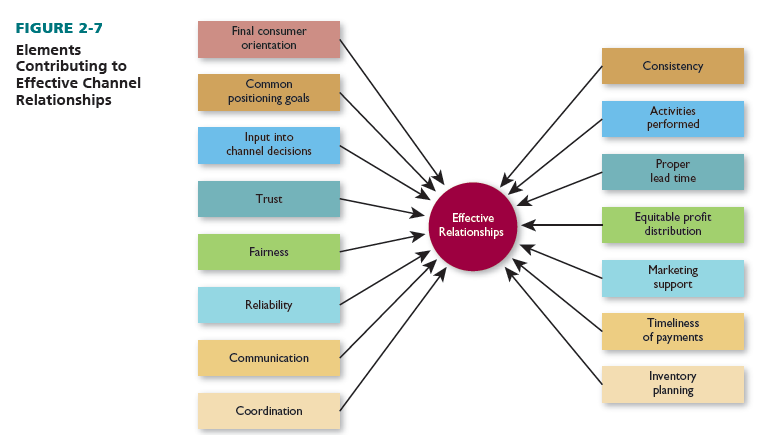

One relationship-oriented practice that some manufacturers and retailers use, especially supermarket chains, is category management, whereby channel members collaborate to manage products by category rather than by individual item. Successful category management is based on these actions: (1) Retailers listen better to customers and stock what they want, (2) Profitability is improved because inventory more closely matches demand, (3) By being better focused, shoppers find each department to be more desirable, (4) Retail buyers have more responsibility and accountability for category results, (5) Retailers and suppliers share data and are more computerized, (6) Retailers and suppliers plan together. See Figure 2-7 for various factors that contribute to effective channel relationships, Category management is discussed further in Chapter 14.

Source: Barry Berman, Joel R Evans, Patrali Chatterjee (2017), Retail Management: A Strategic Approach, Pearson; 13th edition.

After research a few of the weblog posts in your web site now, and I actually like your method of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark web site listing and shall be checking back soon. Pls check out my website online as properly and let me know what you think.