1. Introduction

Danny Meyer is an extremely creative and proactive business thinker and entrepreneur. He has demonstrated this throughout his career—especially with the introduction and expansion of the growing Shake Shack chain. Shake Shack serves a menu of premium burgers, hot dogs, crinkle-cut fries, shakes, frozen custard, beer, and wine. With its fresh and simple, high-quality food, Shake Shack is a fun and lively gathering place with widespread appeal.

2. Meyer’s Basic Philosophy

“People want the highest quality food, but they don’t want the fancy experience anymore,” said Danny Meyer, the chief executive officer (CEO) of Union Square Hospitality Group and the founder of Shake Shack. According to Meyer, some diners are saying, “We like our food better when it’s at a hole in the wall.”

Union Square Hospitality Group’s restaurant portfolio runs the gamut from such tony New York City eateries as the Gramercy Tavern and The Modern at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), to the classy-casual barbecue joint Blue Smoke, to the fast-growing Shake Shack, which started as a hot dog stand in New York City’s Madison Square Park and had grown to more than 90 locations worldwide by mid-2016. According to Shake Shack’s Web site (www.shakeshack.com), at that time, it had outlets in 15 states and the District of Columbia, as well as in four foreign countries and the Middle East.

Danny Meyer was a special guest at the 2016 Convenience Store News Foodservice Summit, held March 15-16, 2016, in partnership with Tyson Convenience, where he participated in an interactive roundtable discussion with about a dozen other leading foodservice executives.

The trailblazing restaurateur noted that in his many travels around the world, the best croissant he’s ever tasted was at a gas station in Uruguay. “People like to be surprised by high/low experiences like that. It’s a wonderful trend for you all,” he said, gesturing to the convenience foodservice retail executives and chefs gathered around the table.

Meyer, whose restaurants and chefs have earned an unprecedented 25 James Beard Awards, had breakfast with the convenience store (c-store) retailers after they spent the previous day visiting unique food concepts throughout the Big Apple on CSNews’ Taste of Manhattan Tour, which included a stop at Meyer’s Shake Shack outlet, his uber-successful hamburger chain. “We started Shake Shack as a hot dog cart in Madison Square Park in 2000,” Meyer recounted, relating how the creation of the fast-casual chain was “a great experiment in combining capitalism with philanthropy.”

Meyer, then spearheading the rehabilitation of Madison Square Park, which had fallen into great disrepair, was asked to supervise the operation of a hot dog cart inside an art exhibit that was part of the park’s renewal effort. Already operating several upscale restaurants near the park and elsewhere in New

York City, Meyer decided to use the hot dog stand to examine “the meaning of hospitality and what that means outside of a fancy restaurant.”

Selling Chicago-style hot dogs (hot dogs topped with yellow mustard, chopped onions, pickle relish, a dill pickle spear, tomato slices, pickled peppers, and celery salt.), the single food stand became extremely successful, drawing lines that numbered more than 100 people at a time. Four years later, the city asked Meyer to operate a permanent 20-foot by 20-foot kiosk in Madison Square Park. Interestingly, that original Shake Shack kiosk focused on milkshakes, not on the hamburgers. “I had no idea it would become so famous for its burgers,” said Meyer. “Every year, we had to renovate the kitchens to increase space for burgers.” In addition to burgers, the restaurant’s menu included its eponymous milkshakes and French fries, and even a ‘Shroom Burger. Since the beginning, Meyer has wanted “everything at Shake Shack to be ‘craveable’.”

He eventually donated the original building, which cost $1 million to build, to the park and continues to operate the Shake Shack unit as a tenant. The Madison Square Park location’s sales continue to grow today. During the summertime, the line typically reaches to outside the park and the wait time for service can be an hour or more. A Web cam on the Shack’s homepage shows the length of the current line in real time for that location.

Unlike more aggressive entrepreneurs, Danny Meyer waited 5 years before opening a second Shake Shack, this time on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. “Shake Shack is the first time we did anything for the second time,” commented Meyer, whose other restaurants are mainly single-unit locations.

Although he eventually expanded Shake Shack to additional locations in New York, as well as in Connecticut, Washington, D.C., Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Texas, Meyer felt that it was important to make every location unique. “We’re proud to be a chain, but who wrote the rule that every link in the chain has to be the same?” he asked.

Twenty percent of the menu at every Shake Shack unit is localized; and none of the units look the same, he noted, pointing to the seats at the New Haven, Connecticut, Shake Shack that look like the seats at the city’s historic Yale Bowl football stadium. Each Shake Shack unit also carries a wide selection of craft beers local to that particular area.

At the 2016 CSNews Foodservice Summit, Meyer had just returned from the grand opening of the first California Shake Shack in West Hollywood in Los Angeles. With international partners, Shake Shack also operates in such locales as Tokyo, London, Istanbul, Moscow, Beirut, Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Doha, Kuwait City, Riyadh, and Jeddah.

3. Chick’n Shack Hatched

As Shake Shack has expanded, so too has its menu, leading to the recent introduction of the restaurant’s first chicken sandwich, the Chick’n Shack—a skinless, marinated chicken breast that arrives vacuum-packed to the store and is then freshly battered and fried, and served with bib lettuce, pickles, and a buttermilk herb mayo.

The Chick’n Shack has been an immediate hit. “In Los Angeles, we had our busiest opening day in our history,” said Meyer, “and the chicken sandwich sold at 80 percent of the beef burger.”

At the Foodservice Summit, Meyer asked the c-store retailers to share what they saw and experienced during the Taste of Manhattan tour. He agreed with them that the eateries on the tour illustrated many of the key trends in the foodser- vice sector, such as the popularity of local, fresh ingredients; the importance of being authentic; and the opportunity to “make food be theater.” Several of the retailer attendees told Meyer they were impressed with the upbeat spirit shown by the young people working at many of the restaurants featured on the tour.

“Even though we call it ‘work,’ hospitality is a team sport,” remarked Meyer, whose first business book, Setting the Table (Harper Collins, 2006), was a New York Times bestseller. It examines the power of warm and sincere hospitality in restaurants, business, and life. “If you think about what sports has in common with hospitality, you notice that ballplayers don’t say they’re going to work today. They say they’re going to play to win. That’s all part of our approach to servant leadership. It’s the belief that the power flows from the bottom up, not the top down,” he said.

“Lately, we’ve been challenging our teams to think about what it would be like if we had no prices for the food on the menu and the guest gets a check for how much they enjoyed the entire experience,” Meyer continued. “That’s not to diminish the importance of food innovation, but if we take food out of the equation, how did we make the guest feel?”

4. Hospitality Included

Meyer made headlines in 2015 with the institution of a “notipping” policy at his restaurant The Modern at New York’s MoMA; and he planned to expand the policy to all his eateries by the end of 2016. A number of observations and personal experiences over the past 20 years led Meyer to launch the paradigm-changing policy on November 15, 2015.

[Authors’ note: In the following paragraphs, Meyer’s no tipping plan is discussed in detail to highlight the many issues involved. However, after just a short time, in 2016, Meyer backed off the no-tipping policy due to customer and employee dissatisfaction. It turned out that many customers wanted to provide tips to ensure the best possible dining service; and the waitstaff wanted to earn the tips for giving customers their outstanding service.]

“I travel around the world to learn about food, and the U.S. culture of tipping is unusual,” Meyer relayed to the group. “There’s no tipping in Asia, and much less in Europe. Tipping came about in the U.S. because we wanted to be more like Europe—150 years ago, when really rich people tipped the help. It was a power thing.”

A couple of years ago, the adjusted minimum wage for tipped employees in New York City became $7.50 per hour. The National Restaurant Association intends to make sure no legislation changes that. Meyer, by the way, paid his waitstaff $9 per hour at that time, $1.50 above the city minimum. [Authors’ note: Today, there are ongoing legislative battles throughout the country about what the minimum wage hourly rate should be in the future.]

“It’s troubled me for the past 20 years. And now, the last 2 years, we are in the midst of the greatest labor crisis in New York City history,” he said.

“The disparity between the wages of tipped employees and non-tipped employees is huge. The average tip in New York City is about 21 percent, which is great for tipped employees, but we can’t find enough skilled cooks to staff our kitchens.”

Meyer reached his own personal tipping point, so to speak, when he found out that he had more Culinary Institute of America-trained chefs working for him as servers than working in his kitchens because they couldn’t make enough money as cooks. “Because of that, and the fact that I never liked the master/ser- vant relationship that tipping implies, I decided that someone has to take a stand and do something about it,” he said.

So, Meyer enacted the following steps at The Modern, and shortly thereafter at Maialino, a Roman trattoria at the Meyer- owned Gramercy Park Hotel:

- He gave all cooks a $2-per-hour raise and built a career ladder for them.

- Menu prices were adjusted upward by about 20 percent and the policy was branded as “Hospitality Included.” Guest receipts no longer had a tipping line.

- He announced the restaurant would share 13.5 percent of its top-line revenues with all employees—tipped and nontipped workers.

- He unfurled the most comprehensive communications program in company history, getting input and feedback from all employees, holding town hall meetings, and conducting one-on-ones with affected employees. He shared with the employees what they would have made under the old tipping system and what they were making under the new no-tipping policy.

The bottom line: Cooks were happier with the wage increase and tipped employees were “kept whole,” according to Meyer. Guests pay about the same. [Authors’ note: Again, many customers and tipped employees were not at all happy with the new plan.]

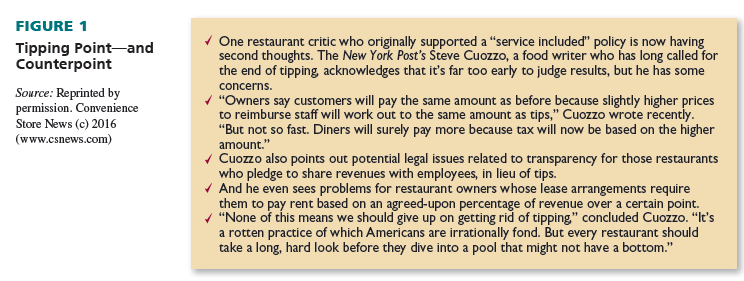

After Meyer introduced “Hospitality Included” at The Modern, at least eight other top chefs and restaurants in New York City have followed suit with similar no-tipping policies. [Authors ’ note: The number of restaurants switching to a notipping policy has been quite small.] Nonetheless, one expert who has been a no-tipping critic, points out some downsides in Figure 1.

5. World-Class Service

Even before the no-tipping experiment, Union Square Hospitality Group was renowned for its world-class customer service. The c-store retailers who participated in the 2016 roundtable were interested in learning how Meyer’s restaurants are able to achieve such a superior level of service from the employees, and, perhaps more importantly, how practical is it to think convenience stores could achieve a superior level of customer service with many of its employees making minimum wage or just slightly higher?

In response, Meyer shared his hiring philosophy, which is to hire people based on their emotional skills, or by having what he calls a high “hospitality quotient.” “We don’t view high labor costs as something happening to us,” he said. “It’s

something we are choosing to do. We feel that it actually drives higher sales volume.” Managers at Meyer’s restaurants are trained to look for six “emotional skills” when interviewing potential new hires. These skills (see Figure 2), with Meyer’s commentary, are:

- Kindness & Optimism: “Skeptics don’t tend to thrive in the hospitality business.”

- Curiosity: “Every day is an opportunity to learn something new.”

- Work Ethic: “I can’t teach you to care about doing things right.”

- Empathy: “What kind of wake do you leave in your path as you go through life?”

- Self-Awareness: “Do you know your own personal weather report?”

- Integrity: “The judgement to do the right thing even if it’s not in your self-interest.”

In addition, Meyer offered some final words of wisdom and encouragement to the foodservice executives. “The smartphone has given people so many choices today. With just the touch of their phone, they can communicate, get car service, get directions, and order food,” he said. “About the only thing it doesn’t do is cook food for you or fill your tank with gas.”

The restaurateur acknowledged what he calls “captive dining” is a thing of the past. “There are a huge number of places to eat. … Today, if I’m eating excellent food in every other channel of my life, why wouldn’t I want that quality at every place I eat?” He recalled one of his first experiences with restaurant-quality food at a convenience store. “I was traveling to Penn State University and had read that Sheetz actually cared about the food experience. It didn’t disappoint. Clearly, Sheetz didn’t view food as a captive audience experience.”

To the group of c-store retailers, Meyer said, “I’ve probably done business with most of your companies before just traveling around the country, and I really admire what you are doing and how your industry is changing, and all of our industries are changing. There’s more and more interest in food and how you make your place so much more than what it once was. I think it is a fascinating thing to grapple with.” Based on what he’s seen of convenience stores’ improved foodservice around the country, he concluded, “You guys are on the right track with foodservice, and people are not going to go back to accepting lower-quality food at a gas station.”

6. Who Is Danny Meyer?

Danny Meyer is CEO of New York-based Union Square Hospitality Group, which includes Union Square Cafe, Gramercy Tavern, Blue Smoke, Jazz Standard, Shake Shack, The Modern, Maialino, Untitled, North End Grill, Marta, Union Square Events, and Hospitality Quotient, a learning and consulting business.

Meyer was born and raised in St. Louis, worked for his father as a tour guide in Rome during college, and then returned to Rome to study international politics. After graduating from Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1980 with a degree in political science, he worked in Chicago for John Anderson’s 1980 independent presidential campaign. He later gained his first restaurant experience in 1984 as an assistant manager at an Italian seafood restaurant in New York City, before returning to Europe to study cooking in both Italy and France. He opened his first restaurant, Union Square Cafe, in 1985 at age 27.

An active national leader in the fight against hunger, Meyer has long served on the boards of Share Our Strength and City Harvest. He is equally active in civic affairs, serving on the boards of NYC & Co., Union Square Partnership, and the Madison Square Park Conservancy.

Source: Barry Berman, Joel R Evans, Patrali Chatterjee (2017), Retail Management: A Strategic Approach, Pearson; 13th edition.

Very interesting information!Perfect just what I was searching for!