A case study protocol has only one thing in common with a survey questionnaire: Both are directed at a single data point—either a single case (even if the case is part of a larger, multiple-case study) or a single respondent.

Beyond this similarity are major differences. The protocol is more than a questionnaire or instrument. First, the protocol contains the instrument but also contains the procedures and general rales to be followed in using the protocol. Second, the protocol is directed at an entirely different party than that of a survey questionnaire, explained below. Third, having a case study protocol is desirable under all circumstances, but it is essential if you are doing a multiple-case study.

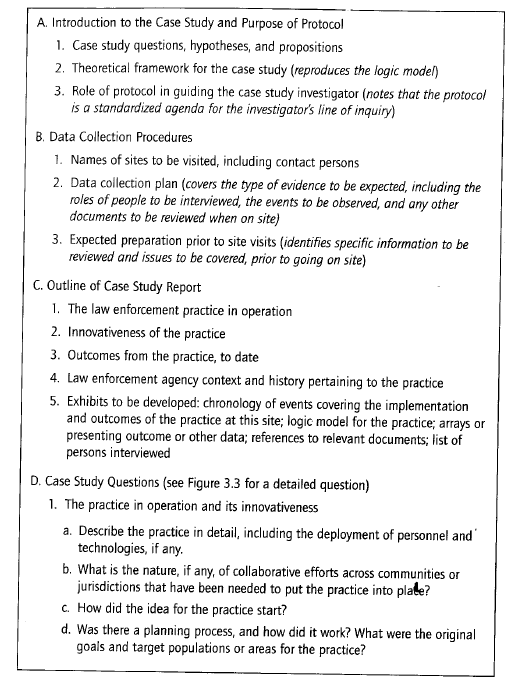

The protocol is a major way of increasing the reliability of case study research and is intended to guide the investigator in carrying out the data collection from a single case (again, even if the single case is one of several in a multiple-case study). Figure 3.2 gives a table of contents from an illustrative protocol, which was used in a study of innovative law enforcement practices supported by federal funds. The practices had been defined earlier through a careful screening process (see later discussion in this chapter for more detail on “screening case study nominations”). Furthermore, because data were to be collected from 18 such cases as part of a multiple-case study, the information about any given case could not be collected in great depth, and thus the number of the case study questions was minimal.

As a general matter, a case study protocol should have the following sections:

- an overview of the case study project (project objectives and auspices, case study issues, and relevant readings about the topic being investigated),

- field procedures (presentation of credentials, access to the case study “sites,” language pertaining to the protection of human subjects, sources of data, and procedural reminders),

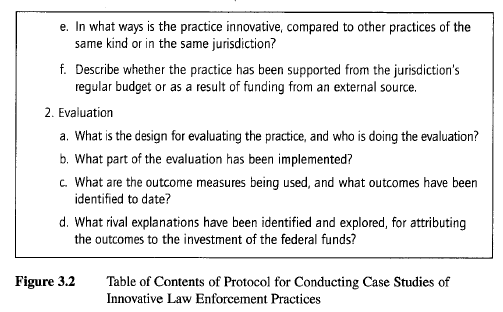

- case study questions (the specific questions that the case study investigator must keep in mind in collecting data, “table shells” for specific arrays of data, and the potential sources of information for answering each question—see Figure 3.3 for an example), and

- a guide for the case study report (outline, format for the data, use and presentation of other documentation, and bibliographical information).

A quick glance at these topics will indicate why the protocol is so important. First, it keeps you targeted on the topic of the case study. Second, preparing the protocol forces you to anticipate several problems, including the way that the case study reports are to be completed. This means, for instance, that you will have to identify the audience for your case study report even before you have conducted your case study. Such forethought will help to avoid mismatches in the long run.

The table of contents of the illustrative protocol in Figure 3.2 reveals another important feature of the case study report: In this instance, the desired report starts by calling for a description of the innovative practice being studied (see item Cl in Figure 3.2)—and only later covers the agency context and history pertaining to the practice (see item C4). This choice reflects the fact that most investigators write too extensively on history and background conditions. While these are important, the description of the subject of the study—the innovative practice—needs more attention.

Each section of the protocol is discussed next.

1. Overview of the Case Study Project

The overview should cover the background information about the project, the substantive issues being investigated, and the relevant readings about the issues.

As for background information, every project has its own context and perspective. Some projects, for instance, are funded by government agencies having a general mission and clientele that need to be remembered in conducting the research. Other projects have broader theoretical concerns or are offshoots, of earlier research studies. Whatever the situation, this type of background information, in summary form, belongs in the overview section.

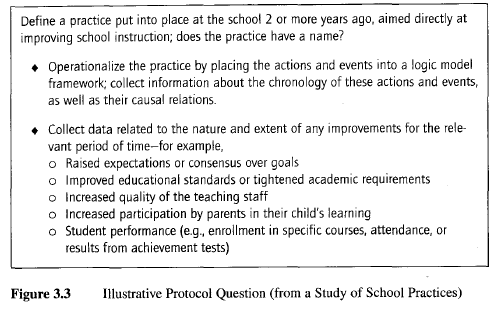

A procedural element of this background section is a statement about the project which you can present to anyone who may want to know about the project, its purpose, and the people involved in conducting and sponsoring the project. This statement can even be accompanied by a letter of introduction, to be sent to all major interviewees and organizations that may be the subject of study. (See Figure 3.4 for an illustrative letter.) The bulk of the overview, however, should be devoted to the substantive issues being investigated. This may include the rationale for selecting the case(s), the propositions or hypotheses being examined, and the broader theoretical or policy relevance of the inquiry. For all of these topics, relevant readings should be cited, and the essential reading materials should be made available to everyone on the case study team.

A good overview will communicate to the informed reader (that is, someone familiar with the general topic of inquiry) the case study’s purpose and setting. Some of the materials (such as a summary describing the project) may be needed for other purposes anyway, so that writing the overview should be seen as a doubly worthwhile activity. In the same vein, a well-conceived overview even may later form the basis for the background and introduction to the final case study report.

2. Field Procedures

Chapter 1 has previously defined case studies as studies of events within their real-life context. This has important implications for defining and designing the case study, which have been discussed in Chapters 1 and 2.

For data collection, however, this characteristic of case studies also raises an important issue, for which properly designed field procedures are essential. You will be collecting data from people and institutions in their everyday situations, not within the controlled confines of a laboratory, the sanctity of a library, or the structured limitations of a survey questionnaire. In a case study, you must therefore learn to integrate real-world events with the needs of the data collection plan. In this sense, you do not have the control over the data collection environment as others might have in using the other research methods discussed in Chapter 1.

Note that in a laboratory experiment, human “subjects” are solicited to enter into the laboratory—an environment controlled nearly entirely by the research investigator. The subject, within ethical and physical constraints, must follow the investigator’s instructions, which carefully prescribe the desired behavior. Similarly, the human “respondent” to a survey questionnaire cannot deviate from the agenda set by the questions. Therefore, the respondent’s behavior also is constrained by the ground rules of the investigator. Naturally, the subject or respondent who does not wish to follow the prescribed behaviors may freely drop out of the experiment or survey. Finally, in the historical archive, pertinent documents may not always be available, but the investigator can inspect what exists at his or her own pace and at a time convenient to her or his schedule. In all three situations, the research investigator closely controls the formal data collection activity.

Doing case studies involves an entirely different situation. For interviewing key persons, you must cater to the interviewee’s schedule and availability, not your own. The nature of the interview is much more open-ended, and an interviewee may not necessarily cooperate fully in sticking to your line of questions. Similarly, in making observations of real-life activities, you are intruding into the world of the subject being studied rather than the reverse; under these conditions, you are the one who may have to make special arrangements, to be able to act as an observer (or even as a participant- observer). As a result, your behavior—and not that of the subject or respondent—is the one likely to be constrained.

This contrasting process of doing data collection leads to the need to have explicit and well-planned field procedures encompassing guidelines for “coping” behaviors. Imagine, for instance, sending a youngster to camp; because you do not know what to expect, the best preparation is to have the resources to be prepared. Case study field procedures should be the same way.

With the preceding orientation in mind, the field procedures of the protocol need to emphasize the major tasks in collecting data, including

- gaining access to key organizations or interviewees;

- having sufficient resources while in the field—including a personal computer, writing instruments, paper, paper clips, and a preestablished, quiet place to write notes privately;

- developing a procedure for calling for assistance and guidance, if needed, from other case study investigators or colleagues;

- making a clear schedule of the data collection activities that are expected to be completed within specified periods of time; and

- providing for unanticipated events, including changes in the availability of interviewees as well as changes in the mood and motivation of the case study investigator.

These are the types of topics that can be included in the field procedures section of the protocol. Depending upon the type of study being done, the specific procedures will vary.

The more operational these procedures are, the better. To take but one minor issue as an example, case study data collection frequently results in the accumulation of numerous documents at the field site. The burden of carrying such bulky documents can be reduced by two procedures. First, the case study team may have had the foresight to bring large, prelabeled envelopes, to mail the documents back to the office rather than carry them. Second, field time may have been set aside for perusing the documents and then going to a local copier facility and copying only the few relevant pages of each document—and then returning the original documents to the informants at the field site. These and other operational details can enhance the overall quality and efficiency of case study data collection.

A final part of this portion of the protocol should carefully describe the procedures for protecting human subjects. First, the protocol should repeat the rationale for the IRB-approved field procedures. Then, the protocol should include the “scripted” words or instructions for the team to use in obtaining informed consent or otherwise informing case study interviewees and other participants of the risks and conditions associated with the research.

3. Case Study Questions

The heart of the protocol is a set of substantive questions reflecting your actual line of inquiry. Some people may consider this part of the protocol to be the case study “instrument.” However, two characteristics distinguish case study questions from those in a survey instrument. (Refer back to Figure 3.3 for an illustrative question from a study of a school program; the complete protocol included dozens of such questions.)

General orientation of questions. First, the questions are posed to you, the investigator, not to an interviewee. In this sense, the protocol is directed at an entirely different party than a survey instrument. The protocol’s questions, in essence, are your reminders regarding the information that needs to be collected, and why. In some instances, the specific questions also may serve as prompts in asking questions during a case study interview. However, the main purpose of the protocol’s questions is to keep the investigator on track as data collection proceeds.

Each question should be accompanied by a list of likely sources of evidence. Such sources may include the names of individual interviewees, documents, or observations. This crosswalk between the questions of interest and the likely sources of evidence is extremely helpful in collecting case study data. Before arriving on the case study scene, for instance, a case study investigator can quickly review the major questions that the data collection should cover.

(Again, these questions form the structure of the inquiry and are not intended as the literal questions to be asked of any given interviewee.)

Levels of questions. Second, the questions in the case study protocol should distinguish clearly among different types or levels of questions. The potentially relevant questions can, remarkably, occur at any of five levels:

Level 1: questions asked of specific interviewees;

Level 2: questions asked of the individual case (these are the questions in the case study protocol to be answered by the investigator during a single case, even when the single case is part of a larger, multiple-case study);

Level 3: questions asked of the pattern of findings across multiple cases;

Level 4: questions asked of an entire study—for example, calling on information beyond the case study evidence and including other literature or published data that may have been reviewed; and

Level 5: normative questions about policy recommendations and conclusions, going beyond the narrow scope of the study.

Of these five levels, you should concentrate heavily on Level 2 for the case study protocol.

The difference between Level 1 and Level 2 questions is highly significant. The two types of questions are most commonly confused because investigators think that their questions of inquiry (Level 2) are synonymous with the specific questions they will ask in the field (Level 1). To disentangle these two levels in your own mind, think again about a detective, especially a wily one. The detective has in mind what the course of events in a crime might have been (Level 2), but the actual questions posed to any witness or suspect (Level 1) do not necessarily betray the detective’s thinking. The verbal line of inquiry is different from the mental line of inquiry, and this is the difference between Level 1 and Level 2 questions. For the case study protocol, explicitly articulating the Level 2 questions is therefore of much greater importance than any attempt to identify the Level 1 questions.

In the field, keeping in mind the Level 2 questions while simultaneously articulating Level 1 questions in conversing with an interviewee is not easy. In a like manner, you can lose sight of your Level 2 questions when examining a detailed document that will become part of the case study evidence (the common revelation occurs when you ask yourself, “Why am I reading this document?”). To overcome these problems, successful participation in the earlier seminar training helps. Remember that being a “senior” investigator means maintaining a working knowledge of the entire case study inquiry. The (Level 2) questions in the case study protocol embody this inquiry.

The other levels also should be understood clearly. A cross-case question, for instance (Level 3), may be whether the larger school districts among your cases are more responsive than smaller school districts or whether complex bureaucratic structures make the larger districts more cumbersome and less responsive. However, this Level 3 question should not be part of the protocol for collecting data from the single case, because the single case only can address the responsiveness of a single school district. The Level 3 question cannot be addressed until the data from all the single cases (in a multiple-case study) are examined. Thus, only the multiple-case analysis can cover Level 3 questions. Similarly, the questions at Levels 4 and 5 also go well beyond any individual case study, and you should note this limitation if you include such questions in the case study protocol. Remember: The protocol is for the data collection from a single case (even when part of a multiple-case study) and is not intended to serve the entire project.

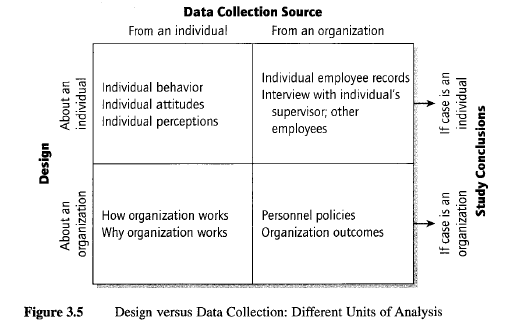

Undesired confusion between unit of data collection and unit of analysis. Related to the distinction between Level 1 and Level 2 questions, a more subtle and serious problem can arise in articulating the questions in the case study protocol. The questions should cater to the unit of analysis of the case study, which may be at a different level from the unit of data collection of the case study. Confusion will occur if, under these circumstances, the data collection process leads to an (undesirable) distortion of the unit of analysis.

The common confusion begins because the data collection sources may be individual people (e.g., interviews with individuals), whereas the unit of analysis of your case study may be a collective (e.g., the organization to which the individual belongs)—a frequent design when the case study is about an organization, community, or social group. Even though your data collection may have to rely heavily on information from individual interviewees, your conclusions cannot be based entirely on interviews as a source of information (you would then have collected information about individuals’ reports about the organization, not necessarily about organizational events as they actually had occurred). In this example, the protocol questions therefore need to be about the organization, not the individual.

However, the reverse situation also can be true. Your case study may be about an individual, but the sources of information can include archival records (e.g., personnel files or student records) from an organization. In this situation, you also would want to avoid basing your conclusions about the individual from the organizational sources of information only. In this example, the protocol questions therefore need to be about the individual, not the organization.

Figure 3.5 illustrates these two situations, where the unit of analysis for the case study is different from the unit of data collection.

Other data collection devices. The protocol questions also can include empty “table shells” (for more detail, see Miles & Huberman, 1994). These are the outlines of a table, defining precisely the “rows” and “columns” of a data array—but in the absence of having the actual data. In this sense, the table shell indicates the data to be collected, and your job is to collect the data called forth by the table. Such table shells help in several ways. First, the table shells force you to identify exactly what data are being sought. Second, they ensure that parallel information will be collected at different sites, where a multiple- case design is being used. Finally, the table shells aid in understanding what will be done with the data once they have been collected.

4. Guide for the Case Study Report

This element is generally missing in most case study plans. Investigators neglect to think about the outline, format, or audience for the case study report until after the data have been collected. Yet, some planning at this preparatory stage—admittedly out of sequence in the typical conduct of most research— means that a tentative outline can (and should) appear in the case study protocol. (Such planning accounts for the arrow between “prepare” and “share” in the figure at the outset of this chapter.)

Again, one reason for the traditional, linear sequence is related to practices with other research methods. One does not worry about the report from an experiment until after the experiment has been completed, because the format of the report and its likely audience already have been dictated by the conventional formats of academic journals. Most reports of experiments follow a similar outline: the posing of the research questions and hypotheses; a description of the research design, apparatus, and data collection procedures; the presentation of the data collected; the analysis of the data; and a discussion of findings and conclusions.

Unfortunately, case study reports do not have such a uniformly acceptable outline. Nor, in many instances, do case study reports end up in journals (Feagin et al., 1991, pp. 269-273). For this reason, each investigator must be concerned, throughout the conduct of a case study, with the design of the final case study report. The problem is not easy to deal with.

In addition, the protocol also can indicate the extent of documentation for the case study report. Properly done, the data collection is likely to lead to large amounts of documentary evidence, in the form of published reports, publications, memoranda, and other documents collected about the case. What is to be done with this documentation, for later presentation? In most studies, the documents are filed away and seldom retrieved. Yet, this documentation is an important part of the “database” for a case study (see Chapter 4) and should not be ignored until after the case study has been completed. One possibility is to have the case study report include an annotated bibliography in which each of the available documents is itemized. The annotations would help a reader (or the investigator, at some later date) to know which documents might be relevant for further inquiry.

In summary, to the extent possible, the basic outline of the case study report should be part of the protocol. This will facilitate the collection of relevant data, in the appropriate format, and will reduce the possibility that a return visit to the case study site will be necessary. At the same time, the existence of such an outline should not imply rigid adherence to a predesigned protocol. In fact, case study plans can change as a result of the initial data collection, and you are encouraged to consider these flexibilities—if used properly and without bias—to be an advantage of the case study method.

EXERCISE 3.4 Developing a Case Study Protocol

Select some phenomenon in need of explanation from the everyday life of your university or school (past or present). Illustrative topics might be, for example, why the university or school changed some policy or how it makes decisions about its curriculum requirements. For these illustrative topics (or some topics of your own choosing), design a case study protocol to collect the information needed to make an adequate explanation. What would be your main research questions or propositions? What specific sources of data would you seek (e.g., persons to be interviewed, documents to be sought, and field observations to be made)? Would your protocol be sufficient in guiding you through the entire process of doing your case study?

Source: Yin K Robert (2008), Case Study Research Designs and Methods, SAGE Publications, Inc; 4th edition.

13 Aug 2021

13 Aug 2021

13 Aug 2021

13 Aug 2021

13 Aug 2021

13 Aug 2021