In identifying the method for your research project, Chapter 1 has shown when you might choose to use the case study method, as opposed to other methods. The next task is to design your case study. For this purpose, as in designing any other type of research investigation, you need a plan or research design.

The development of this research design is a difficult part of doing case studies. Unlike other research methods, a comprehensive “catalog” of research designs for case studies has yet to be developed. There are no textbooks, like those in the biological and psychological sciences, covering such design considerations as the assignment of subjects to different “groups,” the selection of different stimuli or experimental conditions, or the identification of various response measures (see Cochran & Cox, 1957; Fisher, 1935, cited in Cochran & Cox, 1957; Sidowski, 1966). In a laboratory experiment, each of these choices reflects an important logical connection to the issues being studied. Similarly, there are not even textbooks like the well-known volumes by Campbell and Stanley (1966) or by Cook and Campbell (1979) that summarize the various research designs for quasi-experimental situations. Nor have there emerged any common designs—for example, “panel” studies—such as those recognized in doing survey research (see L. Kidder & Judd, 1986, chap. 6).

One pitfall to be avoided, however, is to consider case study designs to be a subset or variant of the research designs used for other methods, such as experiments. For the longest time, scholars incorrectly thought that the case study was but one type of quasi-experimental design (the “one-shot post-test-only” design). This misperception has finally been corrected, with the following statement appearing in a revision on quasi-experimental designs (Cook & Campbell, 1979): “Certainly the case study as normally practiced should not be demeaned by identification with the one-group post-test-only design” (p. 96). In other words, the one-shot, post-test-only design as a quasi-experimental design still may be considered flawed, but the case study has now been recognized as something different. In fact, the case study is a separate research method that has its own research designs.

Unfortunately, case study research designs have not been codified. The following chapter therefore expands on the new methodological ground broken by earlier editions of this book and describes a basic set of research designs for doing single- and multiple-case studies. Although these designs will need to be continually modified and improved in the future, in their present form they will nevertheless help you to design more rigorous and methodologically sound case studies.

1. Definition of Research Designs

Every type of empirical research has an implicit, if not explicit, research design. In the most elementary sense, the design is the logical sequence that connects the empirical data to a study’s initial research questions and, ultimately, to its conclusions. Colloquially, a research design is a logical plan for getting from here to there, where here may be defined as the initial set of questions to be answered, and there is some set of conclusions (answers) about these questions. Between “here” and “there” may be found a number of major steps, including the collection and analysis of relevant data. As a summary definition, another textbook has described a research design as a plan that

guides the investigator in the process of collecting, analyzing, and interpreting observations. It is a logical model of proof that allows the researcher to draw inferences concerning causal relations among the variables under investigation. (Nachmias & Nachmias, 1992, pp. 77-78, emphasis added)

Another way of thinking about a research design is as a “blueprint” for your research, dealing with at least four problems: what questions to study, what data are relevant, what data to collect, and how to analyze the results (Philliber, Schwab, & Samsloss, 1980).

Note that a research design is much more than a work plan. The main purpose of the design is to help to avoid the situation in which the evidence does not address the initial research questions. In this sense, a research design deals with a logical problem and not a logistical problem. As a simple example, suppose you want to study a single organization. Your research questions, however, have to do with the organization’s relationships with other organizations—their competitive or collaborative nature, for example. Such questions can be answered only if you collect information directly from the other organizations and not merely from the one you started with. If you complete your study by examining only one organization, you cannot draw unbiased conclusions about interorganizational partnerships. This is a flaw in your research design, not in your work plan. The outcome could have been avoided if you had developed an appropriate research design in the first place.

2. Components of Research Designs

For case studies, five components of a research design are especially important:

- a study’s questions;

- its propositions, if any;

- its unit(s) of analysis;

- the logic linking the data to the propositions; and

- the criteria for interpreting the findings.

Study questions. This first component has already been described in Chapter 1, which suggested that the form of the question—in terms of “who,” “what,” “where,” “how,” and “why”—provides an important clue regarding the most relevant research method to be used. The case study method is most likely to be appropriate for “how” and “why” questions, so your initial task is to clarify precisely the nature of your study questions in this regard.

More troublesome may be coming up with the substance of the questions. Many students take an initial stab, only to be discouraged when they find the same question(s) already well covered by previous research. Other less desirable questions focus on too trivial or minor parts of an issue. A helpful hint is to move in three stages. In the first, try to use the literature to narrow your interest to a key topic or two, not worrying about any specific research questions. In the second, examine closely—even dissect—a few key studies on your topic of interest. Identify the questions in those few studies and whether they conclude with new questions or loose ends for future research. These may then stimulate your own thinking and imagination, and you may find yourself articulating some potential questions of your own. In the third stage, examine another set of studies on the same topic. They may provide support for your potential questions or even suggest ways of sharpening them.

EXERCISE 2.1 Defining the Boundaries of a Case Study

Select a topic for a case study you would like to do. Identify some research questions to be answered or propositions to be examined by your case study.

How does the naming of these questions or propositions clarify the boundaries of your case study with regard to the time period covered by the case study; the relevant social group, organization, or geographic area; the type of evidence to be collected; and the priorities for data collection and analysis?

Study propositions. As for the second component, each proposition directs attention to something that should be examined within the scope of study. For instance, assume that your research, on the topic of interorganizational partnerships, began with the following question; How and why do organizations collaborate with one another to provide joint services (for example, a manufacturer and a retail outlet collaborating to sell certain computer products)? These “how” and “why” questions, capturing what you are really interested in answering, led yOu to the case study as the appropriate method in the first place. Nevertheless, these “how” and “why” questions do not point to what you should study.

Only if you are forced to state some propositions will you move in the right direction. For instance, you might think that organizations collaborate because they derive mutual benefits. This proposition, besides reflecting an important theoretical issue (that other incentives for collaboration do not exist or are unimportant), also begins to tell you where to look for relevant evidence (to define and ascertain the extent of specific benefits to each organization).

At the same time, some studies may have a legitimate reason for not having any propositions. This is the condition—which exists in experiments, surveys, and the other research methods alike—in which a topic is the subject of “exploration.” Every exploration, however, should still have some purpose. Instead of propositions, the design for an exploratory study should state this purpose, as well as the criteria by which an exploration will be judged successful. Consider the analogy in BOX 4 for exploratory case studies. Can you imagine how you would ask for support from Queen Isabella to do your exploratory study?

BOX 4

“Exploration” as an Analogy for an Exploratory Case Study

When Christopher Columbus went to Queen Isabella to ask for support for his “exploration” of the New World, he had to have some reasons for asking for three ships (Why not one? Why not five?), and he had some rationale for going westward (Why not south? Why not south and then east?). He also had some (mistaken) criteria for recognizing the Indies when he actually encountered it. In short, his exploration began with some rationale and direction, even if his initial assumptions might later have been proved wrong (Wilford, 1992). This same degree of rationale and direction should underlie even an exploratory case study.

Unit of analysis. This third component is related to the fundamental problem of defining what the “case” is—a problem that has plagued many investigators at the outset of case studies (e.g., Ragin & Becker, 1992). For instance, in the classic case study, a “case” may be an individual. Jennifer Platt (1992) has noted how the early case studies in the Chicago school of sociology were life histories of such persons as juvenile delinquents or derelict men. You also can imagine case studies of clinical patients, of exemplary students, or of certain types of leaders. In each situation, an individual person is the case being studied, and the individual is the primary unit of analysis. Information about the relevant individual would be collected, and several such individuals or “cases” might be included in a multiple-case study.

You would still need study questions and study propositions to help identify the relevant information to be collected about this individual or individuals. Without such questions and propositions, you might be tempted to cover “everything” about the individual(s), which is impossible to do. For example, the propositions in studying these individuals might involve the influence of early childhood or the role of peer relationships. Such seemingly general topics nevertheless represent a vast narrowing of the relevant data. The more a case study contains specific questions and propositions, the more it will stay within feasible limits.

Of course, the “case” also can be some event or entity other than a single individual. Case studies have been done about decisions, programs, the implementation process, and organizational change. Feagin et al. (1991) contains some classic examples of these single cases in sociology and political science. Beware of these types of cases—none is easily defined in terms of the beginning or end points of the “case.” For example, a case study of a specific program may reveal (a) variations in program definition, depending upon the perspective of different actors, and (b) program components that preexisted the formal designation of the program. Any case study of such a program would therefore have to confront these conditions in delineating the unit of analysis.

As a general guide, your tentative definition of the unit of analysis (which is the same as the definition of the “case”) is related to the way you have defined your initial research questions. Suppose, for example, you want to study the role of the United States in the global economy. Years ago, Peter Drucker (1986) wrote a provocative essay (not a case study) about fundamental changes in the world economy, including the importance of “capital movements” independent of the flow of goods and services. Using Drucker’s work or some similar theoretical framework, the unit of analysis (or “case”) for your case study might be a country’s economy, an industry in the world marketplace, an economic policy, or the trade or capital flow between countries. Each unit of analysis and its related questions and propositions would call for a slightly different research design and data collection strategy.

Selection of the appropriate unit of analysis will start to occur when you accurately specify your primary research questions. If your questions do not lead to the favoring of one unit of analysis over another, your questions are probably either too vague or too numerous—and you may have trouble doing a case study. However, when you do eventually arrive at a definition of the unit of analysis, do not consider closure permanent. Your choice of the unit of analysis, as with other facets of your research design, can be revisited as a result of discoveries during your data collection (see discussion and cautions about flexibility throughout this book and at the end of this chapter).

Sometimes, the unit of analysis may have been defined one way, even though the phenomenon being studied actually follows a different definition. Most frequently, investigators have confused case studies of neighborhoods with case studies of small groups (as another example, confusing a new technology with the workings of an engineering team in an organization; see BOX 5A). How a geographic area such as a neighborhood copes with racial transition, upgrading, and other phenomena can be quite different from how a small group copes with these same phenomena. For instance, Street Comer Society (Whyte, 1943/1955; see BOX 2A in Chapter 1 of this book) and Tally’s Comer (Liebow, 1967; see BOX 9, this chapter) often have been mistaken for being case studies of neighborhoods when in fact they are case studies of small groups (note that in neither book is the neighborhood geography described, even though the small groups lived in a small area with clear neighborhood implications). BOX 5B, however, presents a good example of how units of analyses can be defined in a more discriminating manner—in the field of world trade.

BOX 5

Defining the Unit of Analysis 5 A. What Is the Unit of Analysis?

5A. What Is the Unit of Analysis?

The Soul of a New Machine (1981) was a Pulitzer Prize-winning book by Tracy Kidder. The book, also a best seller, is about the development of a new minicomputer, produced by Data General Corporation, intended to compete with one produced by a direct competitor, Digital Equipment Corporation (also see BOX 28, Chapter 5, p. 142).

This easy-to-read book describes how Data General’s engineering team invented and developed the new computer. The book begins with the initial conceptualization of the computer and ends when the engineering team relinquishes control of the machine to Data General’s marketing staff.

The book is an excellent example of a case study. However, the book also illustrates a fundamental problem in doing case studies—that of defining the unit of analysis. Is the “case” being studied the minicomputer, or is it about the dynamics of a small group—the engineering team? The answer is critical for understanding how the case study might relate to any broader body of knowledge—that is, whether to generalize to a technology topic or to a group dynamics topic. Because the book is not an academic study, it does not need to, nor does it, provide an answer.

5B. A Clearer Choice among Units of Analysis

Ira Magaziner and Mark Patinkin’s (1989) book, The Silent War: Inside the Global Business Battles Shaping America’s Future, presents nine individual case studies (also see BOX 35, Chapter 5, p. 161). Each case helps the reader to understand a real-life situation of international economic competition.

Two of the cases appear similar but in fact have different main units of analysis. One case, about the Korean firm Samsung, is a case study of the critical policies that make the firm competitive. Understanding Korean economic development is part of the context, and the case study also contains an embedded unit—Samsung’s development of the microwave oven as an illustrative product. The other case, about the development of an Apple computer factory in Singapore, is in fact a case study of Singapore’s critical policies that make the country competitive. The Apple computer factory experience—an embedded unit of analysis—is actually an illustrative example of how the national policies affected foreign investments.

These two cases show how the definition of the main and embedded units of analyses, as well as the definition of the contextual events surrounding these units, depends on the level of inquiry. The main unit of analysis is likely to be at the level being addressed by the main study questions.

Most investigators will encounter this type of confusion in defining the unit of analysis or “case.” To reduce the confusion, one recommended practice is to discuss the potential case with a colleague. Try to explain to that person what questions you are trying to answer and why you have chosen a specific case or group of cases as a way of answering those questions. This may help you to avoid incorrectly identifying the unit of analysis.

Once the general definition of the case has been established, other clarifications in the unit of analysis become important. If the unit of analysis is a small group, for instance, the persons to be included within the group (the immediate topic of the case study) must be distinguished from those who are outside it (the context for the case study). Similarly, if the case is about local services in a specific geographic area, you need to decide which services to cover. Also desirable, for almost any topic that might be chosen, are specific time boundaries to define the beginning and end of the case (e.g., whether to include the entire or only some part of the life cycle of the entity that is to be the case). Answering all of these types of questions will help to determine the scope of your data collection and, in particular, how you will distinguish data about the subject of your case study (the “phenomenon”) from data external to the case (the “context”).

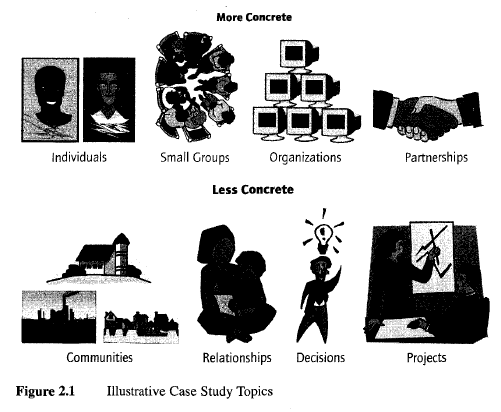

These latter cautions regarding the need for spatial, temporal, and other concrete boundaries underlie a key but subtle aspect in defining your case. The desired case should be some real-life phenomenon, not an abstraction such as a topic, an argument, or even a hypothesis. These abstractions, absent the identification of specific examples or cases, would rightfully serve as the subjects of research studies using other kinds of methods but not case studies. To justify using the case study method, you need to go one step further: You need to define a specific, real-life “case” to represent the abstraction. (For examples of more concrete and less concrete case study topics, see Figure 2.1.)

Take the concept of “neighboring.” Alone, it could be the subject of research studies using methods other than the case study method. The other methods might include a survey of the relationships among neighbors, a history of the evolution of the sense of neighboring and the setting of boundaries, or an experiment in which young children do tasks next to each other to determine the distracting effects, if any, of their neighbors. These examples show how the abstract concept of “neighboring” does not alone produce the grounds for a case study. However, the concept could readily become a case study topic if it were accompanied by your selecting a specific neighborhood (“case”) to be studied and posing study questions and propositions about the neighborhood in relation to the concept of “neighboring.”

One final point pertains to the role of the available research literature and needs to be made about defining the case and the unit of analysis. Most researchers will want to compare their findings with previous research. For this reason, the key definitions used in your study should not be idiosyncratic. Rather, each case study and unit of analysis either should be similar to those previously studied by others or should innovate in clear, operationally defined ways. In this manner, the previous literature also can become a guide for defining the case and unit of analysis.

EXERCISE 2.2 Defining the Unit of Analysis (and the “Case”) for a Case Study

Examine Figure 2.1. Discuss each subject, which illustrates a different unit of analysis. Find a published case study on at least one of these subjects, indicating the actual “case” that was being studied. Understanding that each subject illustrates a different unit of analysis and involves the selection of different cases to be studied, do you think that the more concrete units might be easier to define than the less concrete ones? Why?

Linking data to propositions and criteria for interpreting the findings. The fourth and fifth components have been increasingly better developed in doing case studies. These components foreshadow the data analysis steps in case study research. Because the analytic techniques and choices are covered in

detail in Chapter 5, your main concern during the design phase is to be aware of the main choices and how they might suit your case study. In this way, your research design can create a more solid foundation for the later analysis.

All of the analytic techniques in Chapter 5 represent ways of linking data to propositions: pattern matching, explanation building, time-series analysis, logic models, and cross-case synthesis. The actual analyses will require that you combine or calculate your case study data as a direct reflection of your initial study propositions. For instance, knowing that some or all of your propositions cover a temporal sequence would mean that you might eventually use some type of time-series analysis. Noting this strong likelihood during the design phase would call your attention to the need to be sure you had sufficient procedures to collect time markers as part of your data collection plans.

If you have had limited experience in conducting empirical studies, you will not easily identify the likely analytic technique(s) or anticipate the needed data to use the techniques to their full advantage. More experienced researchers will note how often they have either (a) collected too much data that were not later used in any analysis or (b) collected too little data that prevented the proper use of a desired analytic technique. Sometimes, the latter situation even may force researchers to return to their data collection phase (if they can), to supplement the original data. The more you can avoid any of these situations, the better off you will be.

Criteria for interpreting a study’s findings. Statistical analyses offer some explicit criteria for such interpretations. For instance, by convention, social science considers a p level of less than .05 to demonstrate that observed differences were “statistically significant.” However, much case study analysis will not rely on the use of statistics and therefore calls attention to other ways of thinking about such criteria.

A major and important alternative strategy is to identify and address rival explanations for your findings. Again, Chapter 5 discusses this strategy and how it works more fully. At the design stage of your work, the challenge is to anticipate and enumerate the important rivals, so you will include information about them as part of your data collection. If you only think of rival explanations after data collection has been completed, you will be starting to justify and design a future study, but you will not be helping to complete your current case study. For this reason, specifying important rival explanations is a part of a case study’s research design work.

Summary. A research design should include five components. Although the current state of the art does not provide detailed guidance on the last two, the complete research design should indicate what data are to be collected—as indicated by a study’s questions, its propositions, and its units of analysis. The design also should tell you what is to be done after the data have been collected—as indicated by the logic linking the data to the propositions and the criteria for interpreting the findings.

3. The Role of Theory in Design Work

Covering these preceding five components of research designs will effectively force you to begin constructing a preliminary theory related to your topic of study. This role of theory development, prior to the conduct of any data collection, is one point of difference between case studies and related methods such as ethnography (Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Van Maanen, 1988) and “grounded theory” (Corbin & Strauss, 2007). Typically, these related methods deliberately avoid specifying any theoretical propositions at the outset of an inquiry. As a result, students confusing these methods with case studies wrongly think that, by having selected the case study method, they can proceed quickly into the data collection phase of their work, and they may have been encouraged to make their “field contacts” as quickly as possible. No guidance could be more misleading. Among other considerations, the relevant field contacts depend upon an understanding—or theory—of what is being studied.

Theory development. For case studies, theory development as part of the design phase is essential, whether the ensuing case study’s purpose is to develop or to test theory. Using a case study on the implementation of a new management information system (MIS) as an example (Markus, 1983), the simplest ingredient of a theory is a statement such as the following:

The case study will show why implementation only succeeded when the organization was able to re-structure itself, and not just overlay the new MIS on the old organizational structure. (Markus, 1983)

The statement presents the nutshell of a theory of MIS implementation— that is, that organizational restructuring is needed to make MIS implementation work.

Using the same case, an additional ingredient might be the following statement:

The case study will also show why the simple replacement of key persons was not sufficient for successful implementation. (Markus, 1983)

This second statement presents the nutshell of a rival theory—that is, that MIS implementation fails because of the resistance to change on the part of individual people and that the replacement of such people is the main requirement for implementation to succeed.

You can see that as these two initial ingredients are elaborated, the stated ideas will increasingly cover the questions, propositions, units of analysis, logic connecting data to propositions, and criteria for interpreting the findings—that is, the five components of the needed research design. In this sense, the complete research design embodies a “theory” of what is being studied.

This theory should by no means be considered with the formality of grand theory in social science, nor are you being asked to be a masterful theoretician. Rather, the simple goal is to have a sufficient blueprint for your study, and this requires theoretical propositions, usefully noted by Sutton and Staw (1995) as “a [hypothetical] story about why acts, events, structure, and thoughts occur” (p. 378). Then, the complete research design will provide surprisingly strong guidance in determining what data to collect and the strategies for analyzing the data. For this reason, theory development prior to the collection of any case study data is an essential step in doing case studies. As noted for nonexperi- mental studies more generally, a more elaborate theory desirably points to a more complex pattern of expected results (R R. Rosenbaum, 2002, pp. 5-6 and 277-279). The benefit is a stronger design and a heightened ability to interpret your eventual data.

However, theory development takes time and can be difficult (Eisenhardt, 1989). For some topics, existing works may provide a rich theoretical framework for designing a specific case study. If you are interested in international economic development, for instance, Peter Drucker’s (1986) “The Changed World Economy” is an exceptional source of theories and hypotheses. Drucker claims that the world economy has changed significantly from the past. He points to the “uncoupling” between the primary products (raw materials) economy and the industrial economy, a similar uncoupling between low labor costs and manufacturing production, and the uncoupling between financial markets and the real economy of goods and services. To test these propositions might require different studies, some focusing on the different uncouplings, others focusing on specific industries, and yet others explaining the plight of specific countries. Each different study would likely call for a different unit of analysis. Drucker’s theoretical framework would provide guidance for designing these studies and even for collecting relevant data.

In other situations, the appropriate theory may be a descriptive theory (see BOX 2A in Chapter 1 for another example), and your concern should focus on such issues as (a) the purpose of the descriptive effort, (b) the full but realistic range of topics that might be considered a “complete” description of what is to be studied, and (c) the likely topic(s) that will be the essence of the description. Good answers to these questions, including the rationales underlying the answers, will help you go a long way toward developing the needed theoretical base—and research design—for your study.

For yet other topics, the existing knowledge base may be poor, and the available literature will provide no conceptual framework or hypotheses of note. Such a knowledge base does not lend itself to the development of good theoretical statements, and any new empirical study is likely to assume the characteristic of an “exploratory” study. Nevertheless, as noted earlier with the illustrative case in BOX 4, even an exploratory case study should be preceded by statements about what is to be explored, the purpose of the exploration, and the criteria by which the exploration will be judged successful.

Overall, you may want to gain a richer understanding of how theory is used in case studies by reviewing specific case studies that have been successfully completed. For instance, Yin (2003, chap. 1) shows how theory was used in exploratory, descriptive, and explanatory situations by discussing five actual case studies.

Illustrative types of theories. In general, to overcome the barriers to theory development, you should try to prepare for your case study by doing such things as reviewing the literature related to what you would like to study (also see Cooper, 1984), discussing your topic and ideas with colleagues or teachers, and asking yourself challenging questions about what you are studying, why you are proposing to do the study, and what you hope to learn as a result of the study.

As a further reminder, you should be aware of the full range of theories that might be relevant to your study. For instance, note that the MIS example illustrates MIS “implementation” theory and that this is but one type of theory that can be the subject of study. Other types of theories for you to consider include

- individual theories—for example, theories of individual development, cognitive behavior, personality, learning and disability, individual perception, and interpersonal interactions;

- group theories—for example, theories of family functioning, informal groups, work teams, supervisory-employee relations, and interpersonal networks;

- organizational theories—for example, theories of bureaucracies, organizational structure and functions, excellence in organizational performance, and interorga- nizational partnerships; and

- societal theories—for example, theories of urban development, international behavior, cultural institutions, technological development, and marketplace functions.

Other examples cut across these illustrative types. Decision-making theory (Carroll & Johnson, 1992), for instance, can involve individuals, organizations, or social groups. As another example, a common topic of case studies is the evaluation of publicly supported programs, such as federal, state, or local programs. In this situation, the development of a theory of how a program is supposed to work is essential to the design of the evaluation. In this situation, Bickman (1987) reminds us that the theory needs to distinguish between the substance of the program (e.g., how to make education more effective) and the process of program implementation (e.g., how to install an effective program). The distinction would avoid situations where policy makers might want to know the desired substantive remedies (e.g., findings about a newly effective curriculum) but where an evaluation unfortunately focused on managerial issues (e.g., the need to hire a good project director). Such a mismatch can be avoided by giving closer attention to the substantive theory.

Generalizing from case study to theory. Theory development does not only facilitate the data collection phase of the ensuing case study. The appropriately developed theory also is the level at which the generalization of the case study results will occur. This role of theory has been characterized throughout this book as “analytic generalization” and has been contrasted with another way of generalizing results, known as “statistical generalization.” Understanding the distinction between these two types of generalization may be your most important challenge in doing case studies.

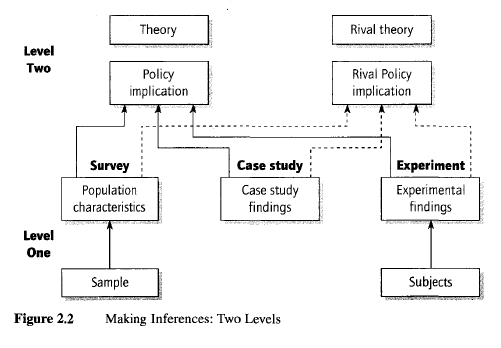

Let us first take the more commonly recognized way of generalizing—statistical generalization—although it is the less relevant one for doing case studies. In statistical generalization, an inference is made about a population (or universe) on the basis of empirical data collected about a sample from that universe. This is shown as a Level One inference in Figure 2.2.1 This method of generalizing is commonly recognized because research investigators have ready access to quantitative formulas for determining the confidence with which generalizations can be made, depending mostly upon the size and internal variation within the universe and sample. Moreover, this is the most common way of generalizing when doing surveys (e.g., Fowler, 1988; Lavrakas, 1987) or analyzing archival data.

A fatal flaw in doing case studies is to conceive of statistical generalization as the method of generalizing the results of your case study. This is because your cases are not “sampling units” and should not be chosen for this reason. Rather, individual case studies are to be selected as a laboratory investigator selects the topic of a new experiment. Multiple cases, in this sense, resemble multiple experiments. Under these circumstances, the mode of generalization is analytic generalization, in which a previously developed theory is used as a template with which to compare the empirical results of the case study.2 If two or more cases are shown to support the same theory, replication may be claimed. The empirical results may be considered yet more potent if two or more cases support the same theory but do not support an equally plausible, rival theory. Graphically, this type of generalization is shown as a Level Two inference in Figure 2.2.

Analytic generalization can be used whether your case study involves one or several cases, which shall be later referenced as single-case or multiple-case studies. Furthermore, the logic of replication and the distinction between statistical and analytic generalization will be covered in greater detail in the discussion of multiple-case study designs. The main point at this juncture is that you should try to aim toward analytic generalization in doing case studies, and you should avoid thinking in such confusing terms as “the sample of cases” or the “small sample size of cases,” as if a single-case study were like a single respondent in a survey or a single subject in an experiment. In other words, in terms of Figure 2.2, you should aim for Level Two inferences when doing case studies.

Because of the importance of this distinction between the two ways of generalizing, you will find repeated examples and discussion throughout the remainder of this chapter as well as in Chapter 5.

Source: Yin K Robert (2008), Case Study Research Designs and Methods, SAGE Publications, Inc; 4th edition.

23 Oct 2019

13 Aug 2021

13 Aug 2021

13 Aug 2021

13 Aug 2021

13 Aug 2021