The PM has three overriding responsibilities to the project. First is the acquisition of resources and personnel. Second is dealing with the obstacles that arise during the course of the project. Third is exercising the leadership needed to bring the project to a successful conclusion primarily by managing the trade-offs necessary to do so and proactively Risk Trade-Offs managing project-related risks.

1. Acquiring Resources

Acquiring resources and personnel is not difficult. Acquiring the necessary quality and quantity of resources and personnel is, however. Senior management typically suffers from a mental condition known as “irrational optimism.” While the disease is rarely painful to anyone except PMs, the suffering among this group may be quite severe.

It has long been known that the farther one proceeds up the managerial ladder, the easier, faster, and cheaper a job appears to be compared to the opinion of the person who has to do the work (Gagnon and Mantel, 1987). The result is that the work plan developed by the project team may have its budget and schedule cut and then cut again as the project is checked and approved at successively higher levels of the organization. At times, an executive in the organization will have a strong interest in a pet project. In order to improve the chance that the pet project will be selected, the executive may deliberately (or subconsciously) understate the resource and personnel commitments required by the project. Whatever the cause, it is the PM’s responsibility to ensure that the project has the appropriate level of resources. When the project team needs specific resources to succeed, there is no acceptable excuse for not getting them—though there may be temporary setbacks.

When a human resource is needed, the problem is further complicated. Most human resources come to the project on temporary assignment from the functional departments of the organization. The PM’s wants are simple—the individual in the organization who is most competent on the specific task to be accomplished. Such individuals are, of course, precisely the people that the functional managers are least happy to release from their departmental jobs for work on the project, either full- or part-time. Those workers the functional manager is prone to offer positions are usually those whom the PM would least like to have.

Lack of functional manager enthusiasm for cooperation with the project has another source. In many organizations, projects are seen as glamorous, interesting, and high- visibility activities. The functional manager may be jealous or even suspicious of the PM who is perceived to have little or no interest in the routine work that is the bread and butter for the parent organization.

2. Fighting Fires and Obstacles

Still another key responsibility of the PM is to deal with obstacles. All projects have their crises—fires that must be quenched. The successful PM is also a talented and seasoned fire fighter. Early in the project’s life cycle, fires are often linked to the need for resources. Budgets get cut, and the general cuts must be transformed into highly specific cuts in the quantities of highly specific resources. An X percent cut must be translated into Y units of this commodity or Z hours of that engineer’s time. (An obvious reaction by the PM is to pad the next budget submitted. As we argue just below and in Chapters 4 and 6, this is unethical, a bad idea, and tends to cause more problems than it solves.)

As work on the project progresses, most fires are associated with technical problems, supplier problems, and client problems. Technical problems occur, for example, when some subsystem (e.g., a computer program) is supposed to work but fails. Typical supplier problems occur when subcontracted parts are late or do not meet specifications. Client problems tend to be far more serious. Most often, they begin when the client asks “Would it be possible for this thing to . . . ?” Again, scope creep.

Most experienced PMs are good fire fighters. If they do not develop this skill, they do not last as PMs. People tend to enjoy doing what they are skilled at doing. Be warned: When you find a skilled fire fighter who fights a lot of fires and enjoys the activity, you may have found an arsonist. At one large, highly respected industrial firm we know, there is a wisecrack commonly made by PMs. “The way to get ahead around here is to get a project, screw it up, and then fix it. If it didn’t get screwed up, it couldn’t have been very hard or very important.” We do not believe that anyone purposely botches projects (or knowingly allows them to be botched). We do, however, suspect that the attitude breeds carelessness because of the belief that they can fix any problem and be rewarded for it.

3. Leadership

In addition to being responsible for acquiring resources for the project and for fighting the project’s fires, the PM is also responsible for making the trade-offs necessary to lead the project to a successful conclusion and proactively managing project related risks through the development of contingency plans. As noted in the previous chapter, the primary roles of the PM are managinge trade-offs and risks and as such these issues are key features of the remainder of this book. In each of the following chapters and particularly in the chapters on budgeting, scheduling, resource allocation, and control, we will deal with many examples of trade-offs and managing risks. They will be specific. At this point, however, we establish some general principles for managing trade-offs.

The PM is the key figure in making trade-offs between project cost, schedule, and scope. Which of these has higher priority than the others is dependent on many factors having to do with the project, the client, and the parent organization. If cost is more important than time for a given project, the PM will allow the project to be late rather than incur added costs. If a project has successfully completed most of its specifications, and if the client is willing, both time and cost may be saved by not pursuing some remaining specifications. It is the client’s choice.

Of the three project goals, scope (specifications and client satisfaction) is usually the most important. Schedule is a close second, and cost is usually subordinate to the other two. Note the word “usually.” There is anecdotal evidence that economic downturns result in an increased level of importance given to cost. There are many other exceptions, and this is another case where the political acuity of the PM is of primary importance. While deliverables are almost always paramount when dealing with an “arm’s-length” client, it is not invariably so for an inside client. If the parent firm has inadequate profits, some specifications may be sacrificed for cost savings. Organizational policy may influence trade-offs. Grumman Aircraft (now a part of Northrop-Grumman) had a longstanding policy of on-time delivery. If a Grumman project for an outside client fell behind on its schedule, resources (costs) were added to ensure on-time delivery.

The global financial crisis caused headaches for project managers around the world. Swanson (2009) reports that in Hong Kong there were thousands of PMs from China suddenly available and willing to manage projects for substantially lower than prevailing wages. As a result, Hong Kong PMs were finding that they needed to increase their value to business in order to compete with the new arrivals from China. Because the Hong Kong firms were outsourcing many project tasks, the Hong Kong PMs acquired new skill sets to deal with people and organizations with whom they have not previously dealt. They learned networking, communication, and leadership skills to augment their technical skills. They also focused on delivering “business” results such as increased revenues, improved profit margins, cost reductions, and they made sure that these appear in the organization’s financial statements.

Another type of trade-off occurs between projects. At times, two or more projects may compete for access to the same resources. This is a major subject in Chapter 6, but the upshot is that added progress on one project may be traded off for less progress on another. If a single PM has two projects in the same part of the project life cycle and makes such a trade-off, it does not matter which project wins, the PM will lose. We strongly recommend that any PM managing two or more projects do everything possible to avoid this problem by making sure that the projects are in different phases of their life cycles. We urge this with the same fervor we would urge parents never to act so as to make it appear that one child is favored over another.

Before leaving the topic of leadership, it is worth discussing a critical dimension of effective leadership, namely, emotional intelligence (EQ). Indeed, researchers have found that EQ is the single best predictor of job performance. For example, bestselling author Daniel Goleman cites research suggesting that EQ is a critical factor in explaining differences between the best leaders and mediocre leaders and that EQ accounted for approximately 90 percent of the success of leaders (Goleman, 1998). Similarly, Swanson (2012) reports that those PMs who use EQ outperform their peer PMs by 32 percent in leadership effectiveness and development.

So what exactly is EQ? Fundamentally, emotional intelligence governs a person’s ability to effectively deal with and in fact harness their emotions to achieve positive outcomes. According to Goleman (1998) , EQ is comprised of four foundational skills: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, and relationship management. Some researchers consider self-awareness and self-management to be personal competencies, and social awareness and relationship management as social competencies.

EQ begins with self-awareness, or a person’s ability to observe and recognize his or her own emotions. Becoming more self-aware of our emotions in turn positions us to better manage our emotions. Thus, self-management is associated with the ability to positively manage our thoughts, behaviors, and actions based on the understanding of our emotions gained through self-awareness. In effect then, self-management reflects our ability to manage our emotional reactions given the situation or circumstances we find ourselves in.

While self-awareness focuses on understanding our own emotions, social awareness is focused on understanding the emotions of others. Understanding our own emotions is certainly important in helping us guide how we respond to a particular set of circumstances. By the same token, understanding the other person’s emotions is also important in helping us choose how we respond. For example, it is likely that the most effective way to respond would be different when a team member was angry versus when the team member was hurt. Thus, social awareness is based on developing effective listening, empathy, and observational skills. The goal is to truly understand what the other person is feeling. Furthermore, when it comes to emotions, there is no right or wrong. Our job is to be an objective observer of these emotions so that we can choose effective courses of action, given the emotions and the people we are interacting with are currently feeling.

Practically speaking, developing your social awareness skills requires developing your listening and observational skills. Effective listening requires an ability to focus your attention on what the other person is saying and not thinking about what you are going to say in response. Effective listening also means letting the other person finish before you respond. It is also useful to give the speaker feedback to show that you are listening such as nodding or smiling while the person is speaking. Pay attention to the main points made by the speaker, the speakers’ tone of voice, how quickly the person is speaking, and the person’s body language. And very importantly, ask questions based on your sincere interest in understanding the other person’s perspective, which will usually not be interpreted as being judgmental.

Self-awareness, self-management, and social awareness are not our end goals. Rather, these are means to the overarching goal of building quality relationships. More specifically, relationship management is based on our ability to use both our awareness of our own emotions and the other person’s emotions to positively manage our interactions and ultimately build quality relationships. Swanson (2012) notes that EQ will lead PMs to ask questions such as: How can we collaborate more effectively with one another on this project? Or, what reservations do you imagine the client will have, and how can we address them? Or, how has this project addressed the needs of all the stakeholders involved?

The good news about EQ is that there are proactive steps you can take to enhance your EQ. Travis Bradberry and Jean Greaves provide an EQ assessment and numerous practical strategies for enhancing EQ in their book Emotional Intelligence 2.0 (Bradberry and Greaves, 2009). This book should be required reading for all PM’s.

4. Negotiation, Conflict Resolution, and Persuasion

It is not possible for the PM to meet these responsibilities without being a skilled negotiator and resolver of conflict. The acquisition of resources requires negotiation. Dealing with problems, conflict, and fires requires negotiation and conflict resolution. The same skills are needed when the PM is asked to lead the project to a successful conclusion— and to make the trade-offs required along the way.

In Chapter 1, we emphasized the presence of conflict in all projects and the resultant need for win-win negotiation and conflict resolution. A PM without these skills cannot be successful. There is no stage of the project life cycle that is not characterized by specific types of conflict. If these are not resolved, the project will suffer and possibly die.

For new PMs, training in win-win negotiation is just as important as training in PERT/ CPM, budgeting, project management software, and project reporting. Such training is not merely useful, it is a necessary requirement for success. While an individual who is not (yet) skilled in negotiation may be chosen as PM for a project, the training should start immediately. A precondition is the ability to handle stress. Much has been written about negotiation and conflict resolution which we shall briefly summarize shortly.

Projects must be selected for funding, and they begin when senior management has been persuaded that they are worthwhile. Projects almost never proceed through their life cycles without change. Changes in scope are common. Trade-offs may change what deliverable is made, how it is made, and when it is delivered. Success at any of these stages depends on the PM’s skill at persuading others to accept the project as well as changes in its methods and scope once it has been accepted. Any suggested change will have supporters and opponents. If the PM suggests a change, others will need to be persuaded that the change is for the better. Senior management must be persuaded to support the change just as the client and the project team may need to be persuaded to accept change in the deliverables or in the project’s methods or timing.

Persuasion is rarely accomplished by “my way or the highway” commands. Neither can it be achieved by locker-room motivational speeches. In an excellent article in the Harvard Business Review, Jay Conger (1998) describes the skill of persuasion as having four essential parts: (1) effective persuaders must be credible to those they are trying to persuade; (2) they must find goals held in common with those being persuaded; (3) they must use “vivid” language and compelling evidence; and (4) they must connect with the emotions of those they are trying to persuade. The article is complete with examples of each of the four essential parts.

Dealing with Conflict Managing conflict is critical to effective leadership, and we now turn our attention to the strategies employed to deal with conflict.

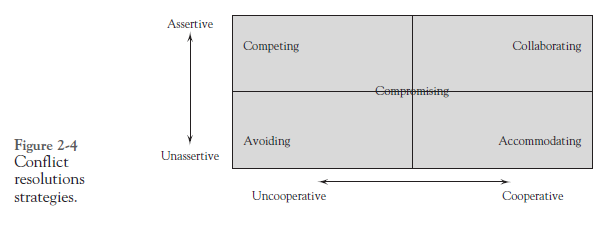

When we think of the ways people deal with conflict, it is helpful to consider how they approach the situation along two dimensions. On the one hand, we can consider how assertive the parties are, which can range from being unassertive to assertive. On the other hand, we can evaluate how cooperative the parties are, ranging from uncooperative to cooperative. Based on these two dimensions, researchers Kenneth Thomas and Ralph Kilmann (1975) identified five strategies people use to deal with conflict, as illustrated in Figure 2-4.

Referring to Figure 2-4, approaching a situation assertively and being unwilling to cooperate is referred to as a “competing” strategy. When a competing strategy is employed, the person is viewing the situation as though someone must lose in order for the other to win, or in this case, I win and you lose (win-lose). This competing strategy may be appropriate in situations where the decision must be made quickly.

Alternatively, when the position is not asserted aggressively but the person is still unwilling to cooperate, we have a conflict “avoiding” strategy. This is a lose-lose strategy because you are neither cooperating with the other person to help them achieve their goals nor are you actively pursuing your own goals. An avoiding strategy might be applied when the issue is not that important to you or you deem the detrimental effects from the conflict outweigh the benefits of resolving the issue in a desirable way.

When you assertively state your position but do so in a spirit of cooperation you are employing a “collaborating” strategy. Here your focus is on achieving your goals but with the recognition that the best solution is one that benefits both parties. Thus, the collaborating strategy can be considered a win-win strategy. This is the preferred strategy in most situations and particularly in situations where the needs of both parties are important.

In situations where you do not assert your position and focus more on cooperating with the other party, you are employing an “accommodating” strategy. In this case, the focus is on resolving the issue from the other person’s point of view. Here the situation can be described as I lose, you win, or lose-win. It would be appropriate to employ the accommodating strategy when you were wrong or the issue is much more important to the other person.

Finally, when you take a middle ground position on both dimensions, you are “compromising.” In these cases, nobody wins and nobody loses. Thus, you have likely arrived at a solution that you and the other party can live with but are not particularly happy about. You might employ a compromising strategy when the potential benefits of trying to develop a win-win solution are exceeded by the costs.

The value of this framework is that it helps us recognize that there are alternative strategies that can be utilized to resolve conflicts. Successful project management requires that when conflict arises, the situation is carefully evaluated and the approach for managing the conflict is proactively chosen in a way that best enhances the quality of the relationship between the parties.

Source: Meredith Jack R., Mantel Jr. Samuel J., Shafer Scott M., Sutton Margaret M. (2017), Project Management in Practice, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 3th Edition.

You have brought up a very good details , thankyou for the post.

Would love to forever get updated great website! .