As most Italians know, scores of these stations have appeared in large Italian cities. There are a few even in centers of a hundred thousand inhabitants, and more continue to appear across Italy. They can be political or commercial in nature. They often have legal problems, but the legislation regarding these stations is ambiguous and evolving. In the period between the genesis of this book and its publication, the situation will already have changed; as it would change during the time it would take for a student to complete this hypothetical thesis.

Therefore, I first must define the exact geographical and chronological limits of my investigation. It could be as limited as “Free Radio Stations from 1975 to 1976,” but within those limits the investigation must be thorough and complete. If I choose to examine only those radio stations located in Milan, I must examine all the radio stations in Milan. Otherwise I risk neglecting the most significant radio station in terms of its programs, ratings, location (suburb, neighborhood, city center), and the cultural composition of its hosts. If I decide to work on a national sample of 30 radio stations, so be it. However, I must establish the selection criteria for this sample. If nationally there are in fact three commercial stations for every five political radio stations, or one extreme right-wing station for every five left-wing stations, my sample must reflect this reality. I cannot choose a sample of 30 stations in which 29 are left-wing or 29 are right-wing.

If I do so, I will represent the phenomenon in proportion to my hopes and fears, instead of to the facts.

I could also decide to renounce the investigation of radio stations as they appear in reality and propose an ideal radio station, much as I tried to prove the existence of centaurs in a possible world. But in this case, the project must not only be organic and realistic (I cannot assume the existence of broadcasting equipment that does not exist, or that is inaccessible to a small private group), but it must also consider the trends of the actual phenomenon. Therefore, a preliminary investigation is indispensable, even in this case.

After I determine the limits of my investigation, I must define exactly what I mean by “free radio station,” so that the object of my investigation is publicly recognizable.

When I use the term “free radio station,” do I mean only a left-wing radio station? Or a radio station built by a small group of people under semilegal circumstances? Or a radio station that is independent of the state monopoly, even if it happens to be well organized and has solely commercial purposes? Or should I consider territorial boundaries, and include only those stations located in the Republic of San Marino or Monte Carlo? However I choose to define the term, I must clarify my criteria and explain why I exclude certain phenomena from the field of inquiry. Obviously the criteria must be defined unequivocally; if I define a free radio station as one that expresses an extreme left-wing political position, I must consider that the term is commonly used in a broader sense. In this case, I must either clarify to my readers that I challenge the common definition of the term, and defend my exclusion of the stations it refers to; or I must choose a less generic term for the radio stations I wish to examine.

At this point, I will have to describe the structure of a free radio station from an organizational, economic, and legal point of view. If full-time professionals staff some stations, and part-time volunteers staff others, I will have to build an organizational typology. I must determine whether these types share common characteristics that can serve as an abstract model of a free radio station, or whether the term covers a series of heterogeneous experiences. Here you can see how the scientific rigor of this analysis is useful also from a practical perspective; if I wanted to open a free radio station myself, I would need to understand the optimal conditions for it to function well.

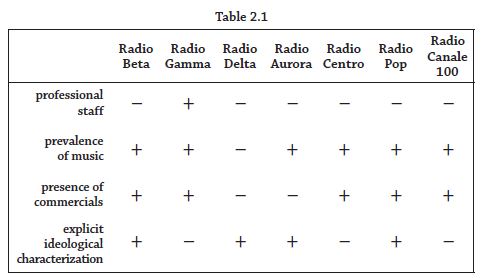

To build a reliable typology, I could draw a table that compared the possible characteristics as they appear in the stations I have examined. I could present the characteristics of a given radio station vertically, and the statistical frequency of the given characteristic horizontally. Below, I provide a simplified and purely hypothetical example with only four parameters: the presence of professional staff, the music- speech ratio, the presence of commercials, and the ideological characterization. Each is applied to seven fictional radio stations.

This table tells me that a nonprofessional, ideologically explicit group runs Radio Pop, that the station broadcasts more music than speech, and that it accepts commercials. It also tells me that the presence of commercials and the abundant music content are not necessarily in contrast with the station’s ideology, since we find two radio stations with similar characteristics, and only one ideological station that broadcasts more speech than music. On the other hand, the presence of commercials and abundant music characterize all nonideological stations. And so on. This table is purely hypothetical and considers only a few parameters and a few stations. Therefore it does not allow us to draw reliable statistical conclusions, and it is only a suggested starting point.

And how then do we obtain this data? We can imagine three sources: official records, managers’ statements, and listening protocols that we will establish below.

Official records: These always provide the most dependable information, but few exist for independent radio stations.

I might first look for an organization’s registration documents at the local public safety authority. I might also find the organization’s constitutive act or a similar document at the local notary, although these documents may not be publicly accessible. In the future, more precise regulation may facilitate more accessible data, but for now this is the extent of what I can expect to find. However, consider that the name of the station, the broadcasting frequency, and the hours of operation are among the official data. A thesis that provided at least these three elements for each station would already be a useful contribution.

Managers’ statements: We can interview each station’s manager. Their words constitute objective data, provided that the interview transcriptions are accurate, and that we use homogeneous criteria for conducting the interviews.

We must devise a single questionnaire, so that all managers respond to the questions that we deem important, and so that the refusal to answer a question becomes a matter of record. The questionnaire need not necessarily be black and white, requiring only answers of “yes” or “no.” If each station manager releases a statement of intent, these statements together could constitute a useful document. Let us clarify the notion of “objective data” in this case: If the director of a particular station states, “We have no political agenda, and we do not accept outside financing,” this may or may not be true. However, the fact that that radio station publicly presents itself in that light is an objective piece of information. Additionally, we may refute this statement based on our critical analysis of the contents of the station’s broadcasts, and this brings us to the third source of information.

Listening protocols: This aspect of the thesis will determine the difference between rigorous and amateurish work. To thoroughly investigate the activity of an independent radio station, we must listen hour after hour for a few days or a week, and devise a sort of “program guide” that indicates what content is broadcast at what time, the length of each program, and the ratio of music to talk. If there are debates, the schedule should indicate the topics, participants, and so on. You will not be able to present all of the data you have collected, but you can include meaningful examples (commentary on the music, witty debate remarks, particular styles of news delivery) that define the artistic, linguistic, and ideological profile of the station you are scrutinizing. It may help to consult the models for radio and TV listening protocols developed over some years by the ARCI Bologna,4 in which listeners determined the duration of news presentation, the recurrence of certain terms, and so on.

Once you have completed this investigation for various radio stations, you could compare your data. For example, you could compare the manner in which two or more radio stations introduced the same song or presented a recent event. You could also compare state-owned radio shows to those of independent stations, noting differences in the ratios of music to speech, news to entertainment, programs to commercials, classical to pop music, Italian to foreign music, traditional pop music to “youth-oriented” pop music, and so on. With a tape recorder and pencil in hand, you will be able to draw many more conclusions through systematic listening than from your interviews with station managers. Sometimes even a simple comparison of commercial sponsors (the ratios between restaurants, cinemas, publishers, etc.) can clarify the obscure financing sources of a given station.

The only condition is that you must not follow impressions or make imprudent conclusions such as, “At noon a particular radio station broadcast pop music and a Pan American commercial, so the station must be proAmerican.” You must also consider what the station broadcast at one o’clock, two o’clock, three o’clock, and on Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday.

If you are investigating many stations, your listening protocol should take one of the following two approaches.

The first is to listen to all the stations simultaneously for one week. You can do this by organizing a group of researchers, each one listening to a different station simultaneously. This is the most rigorous solution because you will be able to compare the various radio stations during the same period. Your other choice is to listen to the stations sequentially, one station per week. This will require hard work, and you must proceed directly from one station to the next so that the listening period is consistent.

The total listening time for all stations should not exceed six months or a year at most, since changes are fast and frequent in this sector, and since it would make no sense to compare the programs of Radio Beta in January with those of Radio Aurora in August.

When you have compiled the data from the three sources outlined above, there is still much left to do. For example, you can do the following:

Establish the size of each station’s audience. Unfortunately, there are no official ratings data, and you cannot trust the station managers’ figures. The only alternative is a random sample telephone survey in which you ask participants to which stations they listen. This is the method followed by RAI, Italy’s national broadcasting company, but it requires an organization that is both specialized and expensive. This is a good example of the difficulty involved in a scientific treatment of a contemporary, topical phenomenon. You cannot rely on personal impressions and conclude, for example, that “the majority of listeners choose Radio Delta” simply because this station is popular among four or five of your friends. (Perhaps a thesis on a subject like Roman history might be a better choice after all, and it will certainly pose fewer research problems.)

Search newspapers and magazines for mentions of the stations you are scrutinizing. Record any opinions of the stations that you find, and describe any controversies. Record the specific laws relevant to the stations’ operations, and explain how various stations follow or elude them. Describe the legal issues that arise. Document the relevant positions of the political parties on the stations you are scrutinizing, and on free radio stations in general. Attempt to establish comparative tables of commercial fees. The managers may not disclose these, or they may provide erroneous data, but you may be able to gather the data elsewhere. For example, if Radio Delta broadcasts advertisements for a particular restaurant, you may be able to solicit data from the restaurant owner.

Record specifically how different radio stations cover a specific event. (For example, the Italian national elections of June 1976 would have provided a perfect opportunity for this part of the project.)

Analyze the linguistic style of the broadcasters. (The ways that they imitate American DJs or public radio hosts, their use of the terminology of specific political groups, their use of dialects, etc.)

Analyze the influence that free radio programs have had on certain public radio programs. Compare the nature of the programming, the linguistic usage, etc.

Thoroughly collect and catalog the opinions that jurists, political leaders, and other public figures express about the stations you are scrutinizing. (Remember that three opinions are only enough for a newspaper article, and that a thorough investigation may require a hundred.)

Collect the existing bibliography on the subject of free radio stations. Collect everything from books and journal articles on analogous experiments in other countries to the articles in the most remote local newspapers or smallest Italian magazines, so that you assemble the most complete bibliography possible.

Let it be clear that you do not have to complete all of these things. Even one of them, if done correctly and exhaustively, can constitute the subject of a thesis. Nor is this the only work to be done. I have only presented these examples to show how, even on a topic as “unscholarly” and devoid of critical literature as this one, a student can write a scientific work that is useful to others, that can be inserted into broader research, that is indispensable to anyone wishing to investigate the subject, and that is free of subjectivity, random observations, and imprudent conclusions.

As we have established, the dichotomy between a scientific and a political thesis is false. It is equally scientific to write a thesis on “The Doctrine of Ideas in Plato” and on “The Politics of ‘Lotta Continua’ from 1974 to 1976.”5 If you intend to do rigorous work, think hard before choosing the second topic, for it is undoubtedly more difficult. It will require superior research skills and scholarly maturity; if nothing else, you will not have a library on which to rely, but instead must effectively create your own.

In any case, we have seen that a student can write scientifically on a subject that others would judge as purely “journalistic,” just as a student can write a journalistic thesis on a topic that most would qualify as scientific, at least from its title.

Source: Eco Umberto, Farina Caterina Mongiat, Farina Geoff (2015), How to write a thesis, The MIT Press.

I am often to running a blog and i really appreciate your content. The article has really peaks my interest. I am going to bookmark your website and keep checking for brand new information.