1. The Purpose of Footnotes

According to a fairly common opinion, a thesis or a book with copious notes exhibits erudite snobbism, and often represents an attempt to pull the wool over the reader’s eyes. Certainly we should not rule out the fact that many authors abound in notes to confer a tone of importance on their work; and that others stuff their notes with nonessential information, perhaps plundering with impunity the critical literature they have examined. Nevertheless, when used appropriately, notes are useful. It is hard to define in general what is appropriate, because this depends on the type of thesis. But we will try to illustrate the cases that require notes, and how the notes should be formatted.

- Use a note to indicate the source of a quote. Too many bibliographical references in the text can interrupt your argument and make your text difficult to read. Naturally there are ways to integrate essential references into the text, thus doing away with the need for notes, such as the author-date system (see section 5.4.3). But in general, notes provide an excellent way to avoid burdening the text with references. If your university doesn’t mandate otherwise, use a footnote for bibliographical references rather than an endnote (that is, a note at the end of the book or the chapter), because a footnote allows the reader to immediately spot the reference.

- Use notes to add additional supporting bibliographical references on a topic you discuss in the text. For example, “on this topic see also so-and-so.” Also in this case, footnotes are more convenient than endnotes.

- Use notes for external and internal cross-references. Once you have treated a topic, you can include the abbreviation “cf.” (for the Latin confer, meaning “to bring together”) in the note to refer the reader to another book, or another chapter or section of your text. If your internal cross-references are essential, you can integrate them into the text. The book you are reading provides many examples of internal cross-references to other sections of the text.

- Use notes to introduce a supporting quote that would have interrupted the text. If you make a statement in the text and then continue directly to the next statement for fluidity, a superscript note reference after the first statement can refer the reader to a note in which a well-known authority backs up your assertion.1

- Use notes to expand on statements you have made in the text.2 Use notes to free your text from observations that, however important, are peripheral to your argument or do nothing more than repeat from a different point of view what you have essentially already said.

- Use notes to correct statements in the text. You may be sure of your statements, but you should also be conscious that someone may disagree, or you may believe that, from a certain point of view, it would be possible to object to your statement. Inserting a partially restrictive note will then prove not only your academic honesty but also your critical spirit.[3]

- Use notes to provide a translation of a quote, or to provide the quote in the original language. If the quote appears in its original language in the main body of the text, you can provide the translation in a note. If however you decide for reasons of fluidity to provide the quote in translation in the main text, you can repeat the quote in its original language in a note.

- Use notes to pay your debts. Citing a book from which you copied a sentence is paying a debt. Citing an author whose ideas or information you used is paying a debt. Sometimes, though, you must also pay debts that are more difficult to document. It is a good rule of academic honesty to mention in a note that, for example, a series of original ideas in your text could not have been born without inspiration from a particular work, or from a private conversation with a scholar.

Whereas notes of types 1, 2, and 3 are more useful as footnotes, notes of types 4 through 8 can also appear at the end of the chapter or of the thesis, especially if they are very long. Yet we will say that a note should never be too long; otherwise it is not a note, it is an appendix, and it must be inserted and numbered as such at the end of the work. At any rate, be consistent: use either all footnotes or all endnotes. Also, if you use short footnotes and longer appendices at the end of the work, do this consistently throughout your thesis.

And once again, remember that if you are examining a homogeneous source, such as the work of only one author, the pages of a diary, or a collection of manuscripts, letters, or documents, you can avoid the notes simply by establishing abbreviations for your sources at the beginning of your work. Then, for every citation, insert the relevant abbreviation and the page or document number in parentheses. For citing classics, follow the conventions in section 3.2.3. In a thesis on medieval authors who are published in Jacques- Paul Migne’s Patrologia Latina, you can avoid hundreds of notes by putting in the text parenthetical references such as this: (PL 30.231). Proceed similarly for references to charts, tables, or illustrations in the text or in the appendix.

2. The Notes and Bibliography System

Let us now consider the note as a means for citation. If in your text you speak of an author or quote some of his passages, the corresponding note should provide the necessary documentation. This system is convenient because, if you use footnotes, the reader knows immediately what author and work you are citing. Yet this process imposes duplication because you must repeat in the final bibliography the same reference you included in the note. (In rare cases in which the note references a work that is unrelated to the specific bibliography of the thesis, there is no need to repeat the reference in the final bibliography. For example, if in a thesis in astronomy I were to cite Dante’s line, “the Love that moves the sun and all the other stars,” the note alone would suffice.)[4] The presence of the references in the note certainly does not invalidate the need for a final bibliography. In fact, the final bibliography provides the material you have consulted at a glance, and it also serves as a comprehensive source for the literature on your particular topic. It would be impolite to force the reader to search the notes page by page to find all the works you have cited.

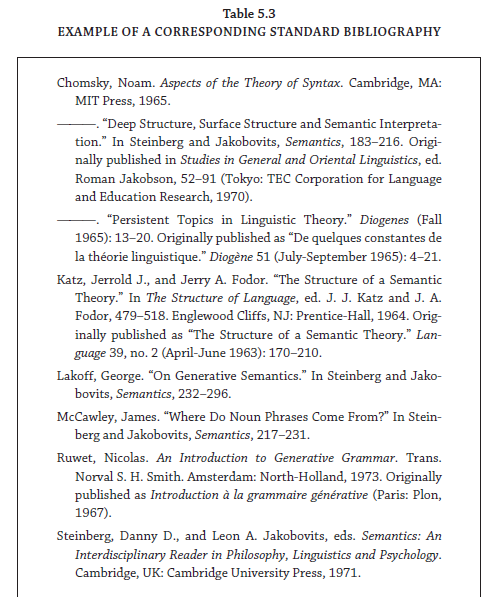

Moreover, the final bibliography provides more complete information than do the notes. For example, in citing a foreign author, the note provides only the title in the original language, while the bibliographical entry will also include a reference to the translation. Furthermore, while usage suggests citing an author by first name and last name in a note, the bibliography presents authors in alphabetical order by last name. Additionally, if the first edition of an article appeared in an obscure journal, and the article was then reprinted in a widely available miscellaneous volume, the note may reference only the miscellaneous volume with the page number of the quote, while the bibliography will also require a reference to the first edition. A note may also abbreviate certain data or eliminate subtitles, while the bibliography should provide all this information.

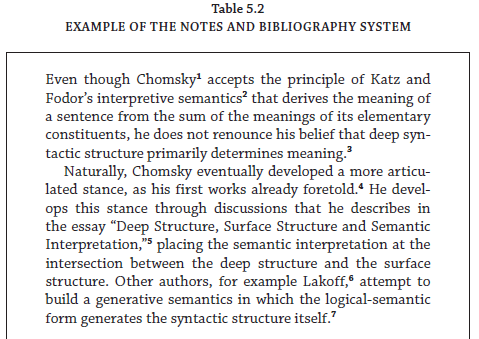

Table 5.2 provides an example of a thesis page with various footnotes, and table 5.3 shows the references as they will appear in the final bibliography.13 Notice the differences between the two. You will see that the notes are more casual than the bibliography, that they do not cite the first edition, and that they aim only to give enough information to enable a reader to locate the text they mention, reserving the complete documentation for the bibliography. Also, the notes do not mention whether the volume in question has been translated. After all, there is the final bibliography in which the reader can find this information.

What are the shortcomings of this system? Take for example footnote 6 of table 5.2. It tells us that Lakoff’s article is in the previously cited miscellaneous volume Semantics. Where was it cited? Luckily, in the same paragraph, and the reference appears in the table’s footnote 5. What if it had been cited ten pages earlier? Should we repeat the reference for convenience? Should we expect the reader to check the bibliography? In this instance, the author-date system is more convenient.

Source: Eco Umberto, Farina Caterina Mongiat, Farina Geoff (2015), How to write a thesis, The MIT Press.

Aw, this was a very nice post. In idea I want to put in writing like this additionally – taking time and precise effort to make an excellent article… however what can I say… I procrastinate alot and by no means appear to get one thing done.

I like what you guys are up also. Such intelligent work and reporting! Carry on the excellent works guys I¦ve incorporated you guys to my blogroll. I think it’ll improve the value of my website 🙂