Like the research methodology model, which forms the basis of this book, the evaluation process is also based upon certain operational steps. It is important for you to remember that the order in the write-up of these steps is primarily to make it easier for you to understand the process. Once you are familiar with these steps, their order can be changed.

Step 1: Determining the purpose of evaluation

In a research study you formulate your research problem before developing a methodology. In an evaluation study too, you need to identify the purpose of undertaking it and develop your objectives before venturing into it. It is important to seek answers to questions such as: ‘Why do I want to do this evaluation?’ and ‘For what purpose would I use the findings?’ Specifically, you need to consider the following matters, and to identify their relevance and application to your situation. Is the evaluation being undertaken to do the following?

- Identify and solve problems in the delivery process of a service.

- Increase efficiency of the service delivery manner.

- determine the impacts of the intervention.

- Train staff for better performance.

- Work out an optimal workload for staff.

- Find out about client satisfaction with the service.

- seek further funding.

- Justify continuation of the programme.

- Resolve issues so as to improve the quality of the service.

- Test out different intervention strategies.

- choose between the interventions.

- Estimate the cost of providing the service.

It is important that you identify the purpose of your evaluation and find answers to your reasons for undertaking it with the active involvement and participation of the various stakeholders. It is also important that all stakeholders — clients, service providers, service managers, funding organisations and you, as an evaluator — agree with the aims of the evaluation. Make sure that all stakeholders also agree that the findings of the evaluation will not be used for any purpose other than those agreed upon. This agreement is important in ensuring that the findings will be acceptable to all, and for developing confidence among those who are to provide the required information do so freely. If your respondents are sceptical about the evaluation, you will not obtain reliable information from them.

Having decided on the purpose of your evaluation, the next step is to develop a set of objectives that will guide it.

Step 2: Developing objectives or evaluation questions

As in a research project, you need to develop evaluation questions, which will become the foundation for the evaluation. Well-articulated objectives bring clarity and focus to the whole evaluation process. They also reduce the chances of disagreement later among various parties.

Some organisations may simply ask you ‘to evaluate the programme’, whereas others may be much more specific. The same may be the situation if you are involved in evaluating your own intervention. If you have been given specific objectives or you are in a situation where you are clear about the objectives, you do not need to go through this step. However, if the brief is broad, or you are not clear about the objectives in your own situation, you need to construct for yourself and others a ‘meaning’ of evaluation.

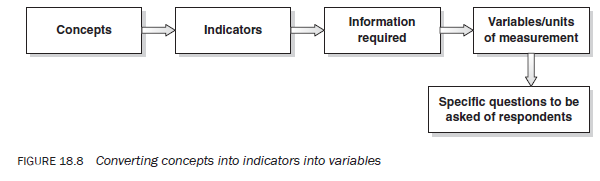

As you know, evaluation can mean different things to different people. To serve the purpose of evaluation from the perspectives of different stakeholders, it is important to involve all stakeholders in the development of evaluation objectives and to seek their agreement with them. You need to follow the same process as for a research study (Chapter 4). The examples in Figure 18.8 may help you to understand more about objective formulation.

Step 3: Converting concepts into indicators into variables

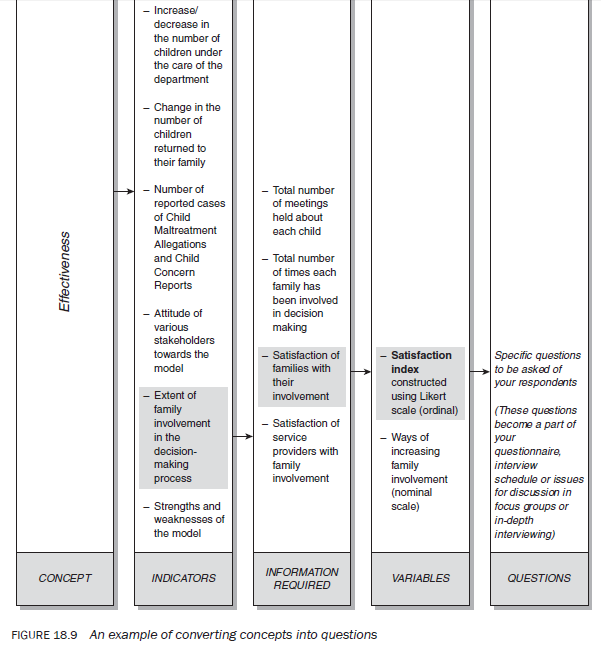

In evaluation, as well as in other research studies, often we use concepts to describe our intentions. For example, we say that we are seeking to evaluate outcomes, effectiveness, impact or satisfaction. The meaning ascribed to such words may be clear to you but may differ markedly from the understanding of others. This is because these terms involve subjective impressions. They need operational definitions in terms of their measurement in order to develop a uniform understanding. When you use concepts, the next problem you need to deal with is the development of a ‘meaning’ for each concept that describes them appropriately for the contexts in which they are being applied. The meaning of a concept in a specific situation is arrived at by developing indicators. To develop indicators, you must answer questions such as: ‘What does this concept mean?’, ‘When can I say that the programme is effective, or has brought about a change, or consumers or service providers are satisfied?’ and ‘On what basis should I conclude that an intervention has been effective?’ Answers to such questions become your indicators and their measurement and assessment become the basis of judgement about effectiveness, impact or satisfaction. Indicators are specific, observable, measurable characteristics or changes that can be attributed to the programme or intervention.

A critical challenge to an evaluator in outcome measurement is identifying and deciding what indicators to use in order to assess how well the programme being evaluated has done regarding an outcome. Remember that not all changes or impacts of a programme may be reflected by one indicator. In many situations you need to have multiple indicators to make an assessment of the success or failure of a programme. Figure 18.9 shows the process of converting concepts into questions that you ask of your respondents.

Some indicators are easy to measure, whereas others may be difficult. For example, an indicator such as the number of programme users is easy to measure, whereas a programme’s impact on self-esteem is more difficult to measure.

In order to assess the impact of an intervention, different types of effectiveness indicators can be used. These indicators may be either qualitative or quantitative, and their measurement may range from subjective-descriptive impressions to objective—measurable—discrete changes. If you are inclined more towards qualitative studies, you may use in-depth interviewing, observation or focus groups to establish whether or not there have been changes in perceptions, attitudes or behaviour among the recipients of a programme with respect to these indicators. In this case, changes are as perceived by your respondents: there is, as such, no measurement involved. On the other hand, if you prefer a quantitative approach, you may use various methods to measure change in the indicators using interval or ratio scales. In all the designs that we have discussed above in outcome evaluation, you may use qualitative or quantitative indicators to measure outcomes.

Now let us take an example to illustrate the process of converting concepts to questions. Suppose you are working in a department concerned with protection of children and are testing a new model of service delivery. Let us further assume that your model is to achieve greater participation and involvement of children, their families and non-statutory organisations working in the community in decision making about children. Your assumption is that with their involvement and participation in developing the proposed intervention strategies, higher compliance will result, which, in turn, will result in the achievement of the desired goals.

As part of your evaluation of the model, you may choose a number of indicators such as the impact on the:

- number of children under the care of the department/agency;

- number of children returned to the family or the community for care;

- number of reported cases of ‘Child Maltreatment Allegations’;

- number of reported cases of ‘Child Concern Reports’;

- extent of involvement of the family and community agencies in the decision-making process about a child.

You may also choose indicators such as the attitude of:

- children, where appropriate, and family members towards their involvement in the decisionmaking process;

- service providers and service managers towards the usefulness of the model;

- non-statutory organisations towards their participation in the decision-making process;

- various stakeholders towards the ability of the model to build the capacity of consumers of the service for self-management;

- family members towards their involvement in the decision-making process.

The scales used in the measurement determine whether an indicator will be considered as ‘soft’ or ‘hard’. Attitude towards an issue can be measured using well-advanced attitudinal scales or by simply asking a respondent to give his/her opinion. The first method will yield a hard indicator while the second will provide a soft one. Similarly, a change in the number of children, if asked as an opinion question, will be treated as a soft indicator.

Figure 18.10 summarises the process of converting concepts into questions, using the example described above. Once you have understood the logic behind this operationalisation, you will find it easier to apply in other similar situations.

Step 4: Developing evaluation methodology

As with a non-evaluative study, you need to identify the design that best suits the objectives of your evaluation, keeping in mind the resources at your disposal. In most evaluation studies the emphasis is on ‘constructing’ a comparative picture, before and after the introduction of an intervention, in relation to the indicators you have selected. On the basis of your knowledge about study designs and the designs discussed in this chapter, you propose one that is most suitable for your situation. Also, as part of evaluation methodology, do not forget to consider other aspects of the process such as:

- From whom will you collect the required information?

- How will you identify your respondents?

- Are you going to select a sample of respondents? If yes, how and how large will it be?

- How will you make initial contact with your potential respondents?

- How will you seek the informed consent of your respondents for their participation in the evaluation?

- How will the needed information be collected?

- How will you take care of the ethical issues confronting your evaluation?

- How will you maintain the anonymity of the information obtained?

- What is the relevance of the evaluation for your respondents or others in a similar situation?

You need to consider all these aspects before you start collecting data.

Step 5: Collecting data

As in a research study, data collection is the most important and time-consuming phase. As you know, the quality of evaluation findings is entirely dependent upon the data collected. Hence, the importance of data collection cannot be overemphasised. Whether quantitative or qualitative methods are used for data collection, it is essential to ensure that quality is maintained in the process.

You can have a highly structured evaluation, placing great emphasis on indicators and their measurement, or you can opt for an unstructured and flexible enquiry: as mentioned earlier, the decision is dependent upon the purpose of your evaluation. For exploratory purposes, flexibility and a lack of structure are an asset, whereas, if the purpose is to formulate a policy, measure the impact of an intervention or to work out the cost of an intervention, a greater structure and standardisation and less flexibility are important.

Step 6: Analysing data

As with research in general, the way you can analyse the data depends upon the way it was collected and the purpose for which you are going to use the findings. For policy decisions and decisions about programme termination or continuation, you need to ascertain the magnitude of change, based on a reasonable sample size. Hence, your data needs to be subjected to a statistical framework of analysis. However, if you are evaluating a process or procedure, you can use an interpretive frame of analysis.

Step 7: Writing an evaluation report

As previously stated, the quality of your work and the impact of your findings are greatly dependent upon how well you communicate them to your readers. Your report is the only basis of judgement for an average reader. Hence, you need to pay extra attention to your writing.

As for a research report, there are different writing styles. In the author’s opinion you should communicate your findings under headings that reflect the objectives of your evaluation. It is also suggested that the findings be accompanied by recommendations pertaining to them. Your report should also have an executive summary of your findings and recommendations.

Step 8: Sharing findings with stakeholders

A very important aspect of any evaluation is sharing the findings with the various groups of stakeholders. It is a good idea to convene a group comprising all stakeholders to communicate what your evaluation has found. Be open about your findings and resist pressure from any interest group. Objectively and honestly communicate what your evaluation has found. It is of utmost importance that you adhere to ethical principles and the professional code of conduct.

As you have seen, the process of a research study and that of an evaluation is almost the same. The only difference is the use of certain models in the measurement of the effectiveness of an intervention. It is therefore important for you to know about research methodology before undertaking an evaluation.

Source: Kumar Ranjit (2012), Research methodology: a step-by-step guide for beginners, SAGE Publications Ltd; Third edition.

Yes! Finally something about website.

I conceive other website proprietors should take this internet site as an model, very clean and fantastic user pleasant design.