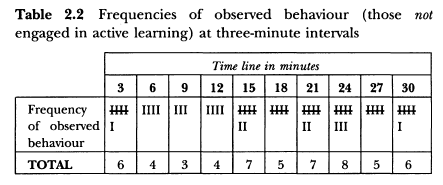

In survey research a sample of the population (however defined) is taken because it is much more economical to do so. A ‘valid’ – i.e. representative – sample is achieved in various ways (not our concern here but see the book in the present series dealing with social surveys (Gillham, 2008)). Validating interval sampling is achieved by taking a given period of observation, dividing it up into, say, three-minute intervals and then calculating whether by taking every other three-minute interval (i.e. every six minutes) you obtain a similar picture to the more frequent sampling. Table 2.2 illustrates a hypothetical example of observed classroom behaviour (children engaged or not in active learning). Here the intervals are every three minutes; the period of observation (counting/recording) is ten seconds – but it could be less. It is usually easier to record the ‘inactive’ children, defined as those who are not:

- reading or writing individually

- choosing a book

- using a computer

- using apparatus or equipment

- involved in making something or painting

- engaged with a teacher or classroom assistant on a learning activity

- working cooperatively with other children.

It is not a difficult matter to record the individual children involved and their gender (you need to be able to identify the children and simply check them at each observation). If you do this ten-second check every three minutes during a 30-minute period you will quickly identify those for whom active learning is a problem; but the total observation time is less than two minutes.

There are two elements here:

- deciding on the length of the interval (when you’re not recording)

- deciding on the duration of the active recording of behavioural events (a function of the frequency of the behaviour and the time needed for recording).

Duration needs to be only as long as is required to check the behavioural events – a practical question; frequency needs to be often enough to give a representative sample. The frequency of observation copes with individual children’s on task/off task variation.

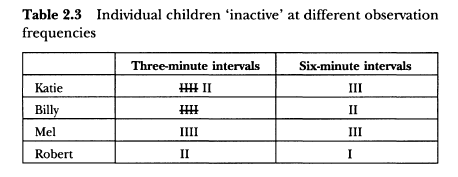

Table 2.2 shows that the average number of ‘inactive’ children at three-minute intervals is 5.5. If we take six- minute intervals it is 5.4: not much in that. But if we are interested in individual children then the higher frequency of observation might be important; for example the hypothetical example in Table 2.3.

In other words the less frequent interval does not differentiate so well in this respect, i.e. those who are more regularly ‘inactive’ are underestimated.

Why sample ?

Since in the above instance you are only ‘active’ as an observer for less than two minutes out of 30 why not carry out continuous monitoring of the children? The answer is that, quite apart from the burden of the task, you don’t get as clear a picture. The successive snapshots tell the story with a precision that is not spurious; and you can validate these frequencies against a class-teacher’s subjective judgement.

To take another example: if an art student is interested in comparing the public’s response to different styles of contemporary painting (e.g. abstract v. representational) in a public art gallery then the task could be to observe how many people stop to look at these different kinds of painting for at least 15 seconds. Looking at paintings is not a momentary business but if no-one stops to look for more than three minutes then a ten-minute interval and 120 seconds for observation would make it unlikely that anyone was counted twice. The student can then move to a room where paintings of the other genre are hung and repeat the exercise; if both kinds are present in the same site then it becomes a simple matter of shifting the observational focus. This is an example of the ‘alternate site’ situation. Within an hour the number of people looking at each of two paintings is observed every five minutes for 120 seconds, alternating one to the other.

This last example is introduced because it commonly leads to this question: surely people know which kinds of painting they prefer? The answer is that it depends on their knowledge and experience; and their ability to express it. In any case we may give a view or opinion but find our eyes drawn to the kind of abstract painting that we might dismiss in response to a general, hypothetical question. We don’t always know what is going to interest or appeal; only our behaviour shows that.

So here we come back to the point made in the first chapter: that you study behaviour not just for its own sake but because it reflects those elusive internal states that underlie what people do, and of which they may not be fully aware.

Source: Gillham Bill (2008), Observation Techniques: Structured to Unstructured, Continuum; Illustrated edition.

9 Aug 2021

9 Aug 2021

9 Aug 2021

9 Aug 2021

9 Aug 2021

9 Aug 2021