Testing is, as we have noted, a process by which a theoretical element is assessed in a real situation. While researchers are free to employ qualitative or quantitative methodological designs to test their propositions, quantitative methods are more frequently used to serve the logic of the testing process.

1. Testing a Hypothesis

When a hypothesis is subjected to a test, it is considered in line with a reality that serves as a reference. It is therefore indispensable to demonstrate, from the outset, how a researcher can determine whether a hypothesis is acceptable or not with regard to a particular reality.

1.1. Is the hypothesis acceptable?

At no moment during the test does the researcher invent. Testing is a matter of finding actual results. All the same, the results of a test should not be taken as true or false in the absolute, but only in relation to the conceptual framework of the test and the specific experimental conditions. A favorable result from this ‘comparison with reality’ – which could be seen as a confirmation of the hypothesis – does not, in fact, constitute decisive proof. It is only a temporarily convincing corroboration. The force with which a hypothesis is corroborated by a given body of facts depends on a variety of factors. Hempel (1966) proposes four corroboration criteria: quantity, diversity, precision and simplicity.

Of these four criteria, simplicity appears to be the most subjective. Popper (1977) argues that the simpler of two hypotheses is the one that has the greatest empirical content. For him, the simplest hypothesis is that which would be easiest to establish as false. While it is true that we cannot prove a hypothesis decisively, it is also true that a single contradictory case is all that is required to show it to be false.

We can push this argument even further by asking whether this credibility can be quantified. If we propose a hypothesis h, with a body of terms k, it is possible to calculate the degree of credibility of h relative to k – expressed as C(h,k). Carnap (1960) designed a general method to define what he called the ‘degree of confirmation’ of a hypothesis in relation to a given body of evidence – as long as both the hypothesis and the evidence are expressed in the same formalized language. Carnap’s concept satisfies all the principles of the theory of probability, and draws on the principles of probabilistic acceptability.

For our purposes here, and in the interests of clarity, we will focus on the essential criteria of an acceptable hypothesis: can it be refuted?

1.2. The hypothetico-deductive method

In practical terms, when researchers undertake to test a hypothesis, a model, or a theory, they generally use the hypothetico-deductive method.

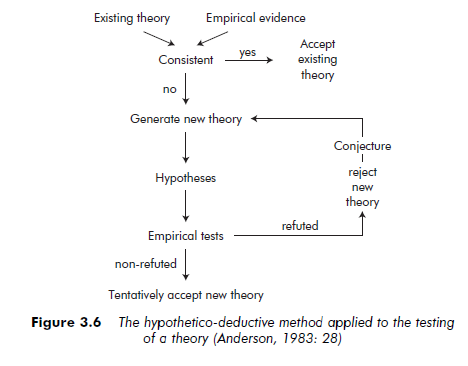

Figure 3.6 (Anderson, 1983) illustrates how the hypothetico-deductive method is used to test hypotheses from a theory’s ‘protective belt’.

More precisely, this process can be broken down into four basic steps:

- We determine which concepts will enable us to respond to our research question. To do so, we must identify, through extensive reference to previous works, the hypotheses, models, or theories that correspond to our subject.

- We observe in what ways the hypotheses, models or theories do not entirely, or perfectly, account for our reality.

- We determine new hypotheses, models or theories.

- We implement a testing phase which will enable us to refute, or not, the hypotheses, models or theories.

Example: An illustration of the hypothetico-deductive method

To explain the hypothetico-deductive method more clearly, we will look at how Miner et al. (1990) approached the following research question: ‘What is the role of interorganizational linkages in organizational transformations and the failure rate of organizations?’

On the basis of existing works, the authors proposed five independent hypotheses. To simplify matters we will present only one of these here.

(h) : Organizations with interorganizational linkages should show a lower failure rate than comparable organizations without such linkages.

We saw in Figure 3.3 that this hypothesis can be illustrated.

The authors proposed to operationalize these concepts by measuring the following variables:

interorganizational linkages —» affiliation with political party failure —» permanent cessation of a newspaper’s publication

Choosing to study the population of Finnish newspapers from 1771 to 1963, the authors used a means comparison test to differentiate the relative weights of linked and non-linked organizations. The results of this test led to the non-refutation of the postulated hypothesis.

In general, it is rare for research to focus on a single hypothesis. For this reason it is important to know how to test a set of hypotheses.

2. Testing a Model

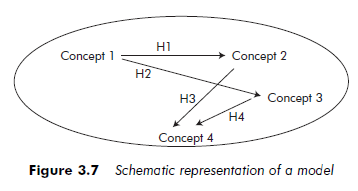

We have seen that a model can take many forms. We will consider here one particular form of model: the realization of a system of logically connected hypotheses (see Figure 3.7).

Before we begin, we should explain that to test a theory, which we have defined (following Lakatos [1974]) as a core surrounded by a protective ring, is to test a hypothesis or a body of hypotheses that belong to the protective ring. That is, to test a theory is to test either a single hypothesis or a model.

The first step in testing such a model is to break down the relationships within it into simple hypotheses, which we can then test one by one. We then arrive at one of the following situations:

- None of the hypotheses are refuted (the model is tentatively accepted).

- Some hypotheses are refuted (the model tentatively accepted in part).

- All the hypotheses are refuted (the model is rejected).

Yet this method is insufficient, although it can provide a useful cursory approach to a complex model. Testing hypotheses should not be confused with testing a model. To test a model involves more than just testing, one by one, the hypotheses of which it is constituted. Reducing a model to juxtaposed hypotheses does not always allow the researcher to take account of the interactions – synergies, moderations and mediations – that operate between them. There are, however, specific ways to test a model as a whole – using structural equations, for example.

The principle of refutability that applies to hypotheses applies equally to models. Models may be rejected (or not rejected) at a given time and in given circumstances. In other words, to test a model comes down to judging the quality, or the representiveness, of it as a simulation of reality. If it is poor, the model is rejected. In the case of the model not being rejected, it can then be said to constitute a useful simulation tool with which to predict the studied phenomenon.

3. Testing Rival Theoretical Elements

We often find ourselves in a situation in which there are a number of rival theories or models. If a researcher is to base his or her work, at least to some extent, on one particular theory or model, he or she must first test each rival theory or model to ascertain how it contributes to understanding the phenomenon under study. The testing method is essentially the same for models and theories.

Faced with competing theories or models, the researcher has to consider how they are to be evaluated and how he or she is to choose between them. This is an epistemological debate, which draws on questions of the status of science itself. It is not our intention to take up a position on this debate here. We will simply propose that a preference for one theory or model above others is neither the result of the justification, through scientific experimentation, of the terms of which the theory or model is made up of, nor is it a logical reduction of the theory or model to experimental findings.

Popper (1977) suggests we should retain the theory or the model that ‘defends itself the most’. That is, the one which seems to be the more representative of reality. In practice, researchers may be led to provisionally accept different models that may serve the needs of their research. To choose between these, Dodd (1968) proposes a hierarchical list of 24 evaluation criteria, which we can group into four categories: formal, semantic, methodological and epistemological. The researcher can evaluate the quality of each model according to these criteria.

Put simply, one way open to the researcher is to test each model individually, using the same testing method, and then to compare the quality to which each represents reality. The researcher compares the deviations observed between values obtained from the model and real values. The model that deviates least from reality is then taken as being ‘more representative of reality’ than the others. It is this model that the researcher will finally retain.

Source: Thietart Raymond-Alain et al. (2001), Doing Management Research: A Comprehensive Guide, SAGE Publications Ltd; 1 edition.

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021