The competitive frame of reference defines which other brands a brand competes with and which should thus be the focus of competitive analysis. Decisions about the competitive frame of reference are closely linked to target market decisions. Deciding to target a certain type of consumer can define the nature of competition because certain firms have decided to target that segment in the past (or plan to do so in the future) or because consumers in that segment may already look to certain products or brands in their purchase decisions.

IDENTIFYING COMPETITORS A good starting point in defining a competitive frame of reference for brand positioning is category membership—the products or sets of products with which a brand competes and that function as close substitutes. It would seem a simple task for a company to identify its competitors. PepsiCo knows Coca-Cola’s Dasani is a major bottled-water competitor for its Aquafina brand; Wells Fargo knows Bank of America is a major banking competitor; and Petsmart.com knows a major online retail competitor for pet food and supplies is Petco.com.

The range of a company’s actual and potential competitors, however, can be much broader than the obvious. To enter new markets, a brand with growth intentions may need a broader or maybe even a more aspirational competitive frame. And it may be more likely to be hurt by emerging competitors or new technologies than by current competitors.

The energy-bar market created by PowerBar ultimately fragmented into a variety of subcategories, including those directed at specific segments (such as Luna bars for women) and some possessing specific attributes (such as the protein-laden Balance and the calorie-control bar Pria). Each represented a subcategory for which the original PowerBar may not be as relevant.4

Firms should broaden their competitive frame to invoke more advantageous comparisons.

Consider these examples:

- In the United Kingdom, the Automobile Association positioned itself as the fourth “emergency service”—along with police, fire, and ambulance—to convey greater credibility and urgency.

- The International Federation of Poker is attempting to downplay some of the gambling image of poker to emphasize the similarity of the card game to other “mind sports” such as chess and bridge.5

- The U.S. Armed Forces changed the focus of its recruitment advertising from the military as patriotic duty to the military as a place to learn leadership skills—a much more rational than emotional pitch that better competes with private industry.6

We can examine competition from both an industry and a market point of view.7 An industry is a group of firms offering a product or class of products that are close substitutes for one another.

Marketers classify industries according to several different factors, such as the number of sellers; degree of product differentiation; presence or absence of entry, mobility, and exit barriers; cost structure; degree of vertical integration; and degree of globalization.

Using the market approach, we define competitors as companies that satisfy the same customer need. For example, a customer who buys a word-processing software package really wants “writing ability”—a need that can also be satisfied by pencils, pens, or, in the past, typewriters. Marketers must overcome “marketing myopia” and stop defining competition in traditional category and industry terms.8 Coca-Cola, focused on its soft drink business, missed seeing the market for coffee bars and fresh-fruit-juice bars that eventually impinged on its soft-drink business.

The market concept of competition reveals a broader set of actual and potential competitors than competition defined in just product category terms. Jeffrey Rayport and Bernard Jaworski suggest profiling a company’s direct and indirect competitors by mapping the buyer’s steps in obtaining and using the product. This type of analysis highlights both the opportunities and the challenges a company faces.9

ANALYZING COMPETITORS Chapter 2 described how to conduct a SWOT analysis that includes a competitive analysis. A company needs to gather information about each competitor’s real and perceived strengths and weaknesses.

Table 10.2 shows the results of a company survey that asked customers to rate its three competitors, A, B, and C, on five attributes. Competitor A turns out to be well known and respected for producing high-quality products sold by a good sales force, but poor at providing product availability and technical assistance. Competitor B is good across the board and excellent in product availability and sales force. Competitor C rates poor to fair on most attributes. This result suggests that in its positioning, the company could attack Competitor A on product availability and technical assistance and Competitor C on almost anything, but it should not attack B, which has no glaring weaknesses. As part of this competitive analysis for positioning, the firm should also ascertain the strategies and objectives of its primary competitors.

Once a company has identified its main competitors and their strategies, it must ask: What is each competitor seeking in the marketplace? What drives each competitor’s behavior? Many factors shape a competitor’s objectives, including size, history, current management, and financial situation. If the competitor is a division of a larger company, it’s important to know whether the parent company is running it for growth or for profits, or milking it.10

Finally, based on all this analysis, marketers must formally define the competitive frame of reference to guide positioning. In stable markets where little short-term change is likely, it may be fairly easy to define one, two, or perhaps three key competitors. In dynamic categories where competition may exist or arise in a variety of different forms, multiple frames of reference may be present, as we discuss below.

1. IDENTIFYING POTENTIAL POINTS-OF-DIFFERENCE AND POINTS-OF-PARITY

Once marketers have fixed the competitive frame of reference for positioning by defining the customer target market and the nature of the competition, they can define the appropriate points-of-difference and points- of-parity associations.11

POINTS-OF-DIFFERENCE Points-of-difference (PODs) are attributes or benefits that consumers strongly associate with a brand, positively evaluate, and believe they could not find to the same extent with a competitive brand.

Associations that make up points-of-difference can be based on virtually any type of attribute or benefit.12 Louis Vuitton may seek a point-of-difference as having the most stylish handbags, Energizer as having the longest-lasting battery, and Fidelity Investments as offering the best financial advice and planning.

Strong brands often have multiple points-of-difference. Some examples are Apple (design, ease-of-use, and irreverent attitude), Nike (performance, innovative technology, and winning), and Southwest Airlines (value, reliability, and fun personality).

Creating strong, favorable, and unique associations is a real challenge, but an essential one for competitive brand positioning. Although successfully positioning a new product in a well-established market may seem particularly difficult, Method Products shows that it is not impossible.13

METHOD PRODUCTS The brainchild of former high school buddies Eric Ryan and Adam Lowry, Method Products was started with the realization that although cleaning and household products are sizable categories by sales, taking up an entire supermarket aisle or more, they are also incredibly boring ones. Method launched a sleek, uncluttered dish soap container that also had a functional advantage—the bottle, shaped like a chess piece, was built to let soap flow out the bottom so users would never have to turn it upside down. This signature product, with its pleasant fragrance, was designed by award-winning industrial designer Karim Rashid. Sustainability also became part of the core of the brand, from sourcing and labor practices to material reduction and the use of nontoxic materials. By creating a line of unique eco-friendly, biodegradable household cleaning products with bright colors and sleek designs, Method grew to a $100 million company in revenues. A big break came with the placement of its product in Target, known for partnering with well-known designers to produce standout products at affordable prices. Because of its limited advertising budget, the company believes its attractive packaging and innovative products must work harder to express the brand positioning. Social media campaigns have been able to put some teeth into the company’s “People Against Dirty” slogan and its desire to make full disclosure of ingredients an industry requirement. Method was acquired by Belgium-based Ecover in 2012; its strong European distribution network will help launch the brand overseas.

Three criteria determine whether a brand association can truly function as a point-of-difference: desirability, deliverability, and differentiability. Some key considerations follow.

- Desirable to consumer. Consumers must see the brand association as personally relevant to them. Select Comfort made a splash in the mattress industry with its Sleep Number beds, which allow consumers to adjust the support and fit of the mattress for optimal comfort with a simple numbering index. Consumers must also be given a compelling reason to believe and an understandable rationale for why the brand can deliver the desired benefit. Mountain Dew may argue that it is more energizing than other soft drinks and support this claim by noting that it has a higher level of caffeine. Chanel No. 5 perfume may claim to be the quintessentially elegant French perfume and support this claim by noting the long association between Chanel and haute couture. Substantiators can also come in the form of patented, branded ingredients, such as NIVEA Wrinkle Control Creme with Q10 co-enzyme.

- Deliverable by the company. The company must have the internal resources and commitment to feasibly and profitably create and maintain the brand association in the minds of consumers. The product design and marketing offering must support the desired association. Does communicating the desired association require real changes to the product itself or just perceptual shifts in the way the consumer thinks of the product or brand? Creating the latter is typically easier. General Motors has had to work to overcome public perceptions that Cadillac is not a youthful, modern brand and has done so through bold designs, solid craftsmanship, and active, contemporary images.14 The ideal brand association is preemptive, defensible, and difficult to attack. It is generally easier for market leaders such as ADM, Visa, and SAP to sustain their positioning, based as it is on demonstrable product or service performance, than it is for market leaders such as Fendi, Prada, and Hermes, whose positioning is based on fashion and is thus subject to the whims of a more fickle market.

- Differentiating from competitors. Finally, consumers must see the brand association as distinctive and superior to relevant competitors. Splenda sugar substitute overtook Equal and Sweet’N Low to become the leader in its category in 2003 by differentiating itself as a product derived from sugar without the associated drawbacks.15 In the crowded energy drink category, Monster has become a nearly $2 billion brand and a threat to category pioneer Red Bull by differentiating itself on its innovative 16-ounce can and an extensive line of products targeting nearly every need state related to energy consumption.16

POINTS-OF-PARITY Points-of-parity (POPs), on the other hand, are attribute or benefit associations that are not necessarily unique to the brand but may in fact be shared with other brands.17 These types of associations come in three basic forms: category, correlational, and competitive.

Category points-of-parity are attributes or benefits that consumers view as essential to a legitimate and credible offering within a certain product or service category. In other words, they represent necessary—but not sufficient— conditions for brand choice. Consumers might not consider a travel agency truly a travel agency unless it is able to make air and hotel reservations, provide advice about leisure packages, and offer various ticket payment and delivery options. Category points-of-parity may change over time due to technological advances, legal developments, or consumer trends, but to use a golfing analogy, they are the “greens fees” necessary to play the marketing game.

Correlational points-of-parity are potentially negative associations that arise from the existence of positive associations for the brand. One challenge for marketers is that many attributes or benefits that make up their POPs or PODs are inversely related. In other words, if your brand is good at one thing, such as being inexpensive, consumers can’t see it as also good at something else, like being “of the highest quality.” Consumer research into the trade-offs consumers make in their purchasing decisions can be informative here. Below, we consider strategies to address these trade-offs.

Competitive points-of-parity are associations designed to overcome perceived weaknesses of the brand in light of competitors’ points-of-difference. One good way to uncover key competitive points-of-parity is to role-play competitors’ positioning and infer their intended points-of-difference. Competitor’s PODs will, in turn, suggest the brand’s POPs.

Regardless of the source of perceived weaknesses, if, in the eyes of consumers, a brand can “break even” in those areas where it appears to be at a disadvantage and achieve advantages in other areas, the brand should be in a strong—and perhaps unbeatable—competitive position. Consider the introduction of Hyundai Motor Company—the biggest carmaker in South Korea and one of the top ten global auto companies.18

HYUNDAI CARS In recent years, Hyundai Motor Company has succeeded in boosting its presence in the world car market by setting up overseas production bases and engaging in aggressive marketing. As South Korea’s largest and the world’s fifth largest automaker, Hyundai has driven its sales growth through improvements in quality and design. While its rivals are using reliability and fuel economy to build market share, Hyundai has taken the formula further with a focus on making its cars more attractive and often at lower prices. The brand’s goal is to entice customers with the speed and appeal of luxury European models, but at non-premium prices. To win the hearts of car buyers, Hyundai engages credible and attractive spokespersons, like Bollywood actor Shah Rukh Khan and German football celebrity Jurgen Klinsmann, to help communicate its value proposition. To improve its overall brand perception, the company has a long-term commitment with FIFA to sponsor the FIFA World Cup until 2022.

POINTS-OF-PARITY VERSUS POINTS-OF-DIFFERENCE For an offering to achieve a point-of-parity on a particular attribute or benefit, a sufficient number of consumers must believe the brand is “good enough” on that dimension. There is a zone or range of tolerance or acceptance with points-of-parity. The brand does not literally need to be seen as equal to competitors, but consumers must feel it does well enough on that particular attribute or benefit. If they do, they may be willing to base their evaluations and decisions on other factors more favorable to the brand. A light beer presumably would never taste as good as a full-strength beer, but it would need to taste close enough to be able to effectively compete.

Often, the key to positioning is not so much achieving a point-of-difference as achieving points-of-parity!

VISA VERSUS AMERICAN EXPRESS category is that it is the most widely available card, which underscores the category’s main benefit of convenience. American Express, on the other hand, has built the equity of its brand by highlighting the prestige associated with the use of its card. Visa and American Express now compete to create points-of-parity by attempting to blunt each other’s advantage. Visa offers gold and platinum cards to enhance the prestige of its brand, and for years it advertised, “It’s Everywhere You Want to Be,” showing desirable travel and leisure locations that accept only the Visa card to reinforce both its own exclusivity and its acceptability. American Express has substantially increased the number of merchants that accept its cards and created other value enhancements while also reinforcing its cachet through advertising that showcases celebrities such as Robert De Niro, Tina Fey, Ellen DeGeneres, and Beyonce as well as promotions for exclusive access to special events.

MULTIPLE FRAMES OF REFERENCE It is not uncommon for a brand to identify more than one actual or potential competitive frame of reference, if competition widens or the firm plans to expand into new categories. For example, Starbucks could define very distinct sets of competitors, suggesting different possible POPs and PODs as a result:19

- Quick-serve restaurants and convenience shops (McDonald’s and Dunkin’ Donuts)—Intended PODs might be quality, image, experience, and variety; intended POPs might be convenience and value.

- Home and office consumption (Folgers, NESCAFE instant, and Green Mountain Coffee K-Cups)—Intended PODs might be quality, image, experience, variety, and freshness; intended POPs might be convenience and value.

- Local cafes—Intended PODs might be convenience and service quality; intended POPs might be product quality, variety, price, and community.

Note that some potential POPs and PODs for Starbucks are shared across competitors; others are unique to a particular competitor.

Under such circumstances, marketers have to decide what to do. There are two main options with multiple frames of reference. One is to first develop the best possible positioning for each type or class of competitors and then see whether there is a way to create one combined positioning robust enough to effectively address them all. If competition is too diverse, however, it may be necessary to prioritize competitors and then choose the most important set of competitors to serve as the competitive frame. One crucial consideration is not to try to be all things to all people—that leads to lowest-common-denominator positioning, which is typically ineffective.

Finally, if there are many competitors in different categories or subcategories, it may be useful to either develop the positioning at the categorical level for all relevant categories (“quick-serve restaurants” or “supermarket take-home coffee” for Starbucks) or with an exemplar from each category (McDonald’s or NESCAFE for Starbucks).

STRADDLE POSITIONING Occasionally, a company will be able to straddle two frames of reference with one set of points-of-difference and points-of-parity. In these cases, the points-of-difference for one category become points-of-parity for the other and vice versa. Subway restaurants are positioned as offering healthy, goodtasting sandwiches. This positioning allows the brand to create a POP on taste and a POD on health with respect to quick-serve restaurants such as McDonald’s and Burger King and, at the same time, a POP on health and a POD on taste with respect to health food restaurants and cafes.

Straddle positions allow brands to expand their market coverage and potential customer base. Another example is BMW.20

BMW When BMW first made a strong competitive push into the U.S. market in the late 1970s, it positioned the brand as the only automobile that offered both luxury and performance. At that time, consumers saw U.S. luxury cars as lacking performance and U.S. performance cars as lacking luxury. By relying on the design of its cars, its German heritage, and other aspects of a well-conceived marketing program, BMW was able to simultaneously achieve: (1) a point-of-difference on luxury and a point-of-parity on performance with respect to U.S. performance cars like the Chevy Corvette and (2) a point-of-difference on performance and a point-of-parity on luxury with respect to U.S. luxury cars like Cadillac. The clever slogan “The Ultimate Driving Machine” effectively captured the newly created umbrella category: luxury performance cars.

Although a straddle positioning is often attractive as a means of reconciling potentially conflicting consumer goals and creating a “best of both worlds” solution, it also carries an extra burden. If the points-of-parity and points-of-difference are not credible, the brand may not be viewed as a legitimate player in either category. Many early personal digital assistants (PDAs), or palm-sized computers, that unsuccessfully tried to straddle categories ranging from pagers to laptop computers provide a vivid illustration of this risk.

2. CHOOSING SPECIFIC POPs AND PODs

To build a strong brand and avoid the commodity trap, marketers must start with the belief that you can differentiate anything. Michael Porter urged companies to build a sustainable competitive advantage.21 Competitive advantage is a company’s ability to perform in one or more ways that competitors cannot or will not match.

Some companies are finding success. Pharmaceutical companies are developing biologics, medicines produced using the body’s own cells rather than through chemical reactions in a lab, because they are difficult for copycat pharmaceutical companies to make a generic version of when they go off patent. Roche Holding will enjoy an advantage of at least three years with its $7 billion-a-year in sales biologic rheumatoid arthritis treatment Rituxan before a biosimilar copycat version is introduced.22

But few competitive advantages are inherently sustainable. At best, they may be leverageable. A leverageable advantage is one that a company can use as a springboard to new advantages, much as Microsoft has leveraged its operating system to Microsoft Office and then to networking applications. In general, a company that hopes to endure must be in the business of continuously inventing new advantages that can serve as the basis of points-of-difference.23

Marketers typically focus on brand benefits in choosing the points-of-parity and points-of-difference that make up their brand positioning. Brand attributes generally play more of a supporting role by providing “reasons to believe” or “proof points” as to why a brand can credibly claim it offers certain benefits. Marketers of Dove soap, for example, will talk about how its attribute of one-quarter cleansing cream uniquely creates the benefit of softer skin. Singapore Airlines can boast about its superior customer service because of its better- trained flight attendants and strong service culture. Consumers are usually more interested in benefits and what exactly they will get from a product. Multiple attributes may support a certain benefit, and they may change over time.

MEANS OF DIFFERENTIATION Any product or service benefit that is sufficiently desirable, deliverable, and differentiating can serve as a point-of-difference for a brand. The obvious, and often the most compelling, means of differentiation for consumers are benefits related to performance (Chapters 13 and 14). Swatch offers colorful, fashionable watches; GEICO offers reliable insurance at discount prices.

Sometimes changes in the marketing environment can open up new opportunities to create a means of differentiation. Eight years after it launched Sierra Mist and with sales stagnating, Pepsico tapped into rising consumer interest in natural and organic products to reposition the lemon-lime soft drink as all-natural with only five ingredients: carbonated water, sugar, citric acid, natural flavor, and potassium citrate.24

Often a brand’s positioning transcends its performance considerations. Companies can fashion compelling images that appeal to consumers’ social and psychological needs. The primary explanation for Marlboro’s extraordinary worldwide market share (about 30 percent) is that its “macho cowboy” image has struck a responsive chord with much of the cigarette-smoking public. Wine and liquor companies also work hard to develop distinctive images for their brands. Even a seller’s physical space can be a powerful image generator. Hyatt Regency Hotels developed a distinctive image with its atrium lobbies.

To identify possible means of differentiation, marketers have to match consumers’ desire for a benefit with their company’s ability to deliver it. For example, they can design their distribution channels to make buying the product easier and more rewarding. Back in 1946, pet food was cheap, not too nutritious, and available exclusively in supermarkets and the occasional feed store. Dayton, Ohio-based Iams found success selling premium pet food through regional veterinarians, breeders, and pet stores.

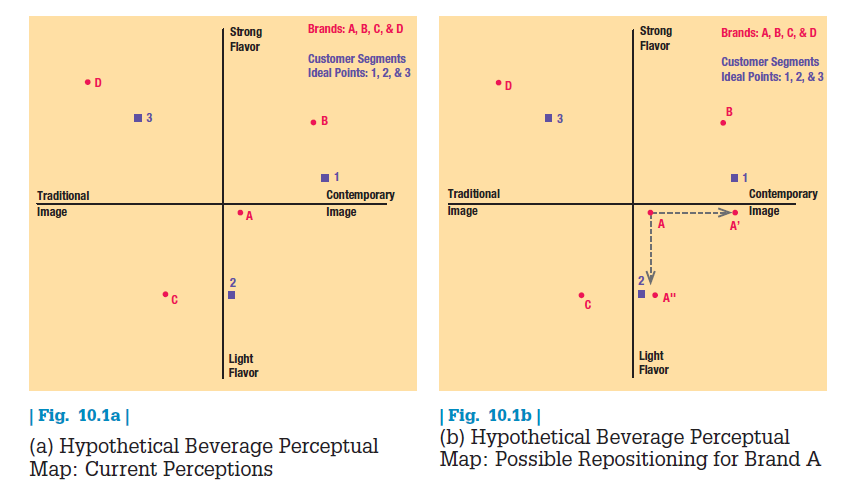

PERCEPTUAL MAPS For choosing specific benefits as POPs and PODs to position a brand, perceptual maps may be useful. Perceptual maps are visual representations of consumer perceptions and preferences. They provide quantitative pictures of market situations and the way consumers view different products, services, and brands along various dimensions. By overlaying consumer preferences with brand perceptions, marketers can reveal “holes” or “openings” that suggest unmet consumer needs and marketing opportunities.25

For example, Figure 10.1(a) shows a hypothetical perceptual map for a beverage category. The four brands—A, B, C, and D—vary in terms of how consumers view their taste profile (light versus strong) and personality and imagery (contemporary versus modern). Also displayed on the map are ideal point “configurations” for three market segments (1, 2, and 3). The ideal points represent each segment’s most preferred (“ideal”) combination of taste and imagery.

Consumers in Segment 3 prefer beverages with a strong taste and traditional imagery. Brand D is well positioned for this segment because the market strongly associates it with both these benefits. Given that none of the competitors is seen as anywhere close, we would expect Brand D to attract many of the Segment 3 customers.

Brand A, on the other hand, is seen as more balanced in terms of both taste and imagery. Unfortunately, no market segment seems to really desire this balance. Brands B and C are better positioned with respect to Segments 2 and 3, respectively.

- By making its image more contemporary, Brand A could move to A’ to target consumers in Segment 1 and achieve a point-of-parity on imagery and maintain its point-of-difference on taste profile with respect to Brand B.

- By changing its taste profile to make it lighter, Brand A could move to A’’ to target consumers in Segment 2 and achieve a point-of-parity on taste profile and maintain its point-of-difference on imagery with respect to Brand C.

Deciding which repositioning is most promising, A’ or A”, would require detailed consumer and competitive analysis on a host of factors—including the resources, capabilities, and likely intentions of competing firms—to identify the markets where consumers can profitably be served.

EMOTIONAL BRANDING Many marketing experts believe a brand positioning should have both rational and emotional components. In other words, it should contain points-of-difference and points-of-parity that appeal to both the head and the heart.26

Strong brands often seek to build on their performance advantages to strike an emotional chord with customers. When research on scar-treatment product Mederma found that women were buying it not just for the physical treatment but also to increase their self-esteem, the marketers of the brand added emotional messaging to what had traditionally been a practical message that stressed physician recommendations: “What we have done is supplement the rational with the emotional.”27 Kate Spade is another brand that blends functional and emotional in its positioning.28

KATE SPADE Although only a little more than 20 years old, Kate Spade has evolved from a bags-only brand to a much more diversified fashion brand. Launched by husband-and-wife team Kate and Andy Spade—who have since sold their stake—the brand was initially known for a tiny, minimalist-looking black bag. In 2007, a new creative director, Deborah Lloyd, brought a stronger style sensibility to help hit the Kate Spade customer sweet spot of being “the most interesting person in the room.” With greater emphasis on marrying form and function, the brand expanded into apparel and jewelry and has become the centerpiece of a revamped Liz Claiborne (now known as Fifth & Pacific). Accessories are updated constantly, and there are frequent new merchandise introductions. A men’s brand (Jack Spade) and a more casual, affordable fashion brand targeting younger millennium consumers (Kate Spade Saturday) have also been launched. Kate Spade has made a strong e-commerce push to complement its 200-plus stores; 20 percent of sales come from online channels. The company has also made a well-integrated social media foray, using Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr, Pinterest, YouTube, FourSquare, and Spotify to reinforce its core brand values of “patterns, colors, fun food and classic New York moments.” It has made a move into Europe and Asia and has especially set its sights on China.

A person’s emotional response to a brand and its marketing will depend on many factors. An increasingly important one is the brand’s authenticity.29 Brands such as Hershey’s, Kraft, Crayola, Kellogg’s, and Johnson & Johnson that are seen as authentic and genuine can evoke trust, affection, and strong loyalty.30

Authenticity also has functional value. Family farmer-owned Welch’s—1,150 Concord and Niagara grape farmers make up the National Grape Cooperative—is seen by consumers as “wholesome, authentic and real.” The brand reinforces those credentials by focusing on its local sourcing of ingredients, increasingly important for consumers who want to know where their foods come from and how they were made.31

By successfully differentiating themselves, emotional brands can also provide financial payoffs. As part of its IPO, the UK mobile phone operator O2 was rebranded from British Telecom’s struggling BT Cellnet, based on a powerful emotional campaign about freedom and enablement. When customer acquisition, loyalty, and average revenue soared, the business was quickly acquired by Spanish multinational Telefonica for more than three times its IPO price.32

3. BRAND MANTRAS

To further focus brand positioning and guide the way their marketers help consumers think about the brand, firms can define a brand mantra.33 A brand mantra is a three- to five-word articulation of the heart and soul of the brand and is closely related to other branding concepts like “brand essence” and “core brand promise.” Its purpose is to ensure that all employees within the organization and all external marketing partners understand what the brand is most fundamentally to represent with consumers so they can adjust their actions accordingly.

ROLE OF BRAND MANTRAS Brand mantras are powerful devices. By highlighting points-of-difference, they provide guidance about what products to introduce under the brand, what ad campaigns to run, and where and how to sell the brand. Their influence can even extend beyond these tactical concerns. Brand mantras can guide the most seemingly unrelated or mundane decisions, such as the look of a reception area and the way phones are answered. In effect, they create a mental filter to screen out brand-inappropriate marketing activities or actions of any type that may have a negative bearing on customers’ impressions.

Brand mantras must economically communicate what the brand is and what it is not. What makes a good brand mantra? McDonald’s “Food, Folks, and Fun” captures its brand essence and core brand promise. Two other high- profile and successful examples—Nike and Disney—show the power and utility of a well-designed brand mantra.

NIKE Nike has a rich set of associations with consumers, based on its innovative product designs, its sponsorships of top athletes, its award-winning communications, its competitive drive, and its irreverent attitude. Internally, Nike marketers adopted the three-word brand mantra, “authentic athletic performance,” to guide their marketing efforts. Thus, in Nike’s eyes, its entire marketing program—its products and the way they are sold—must reflect that key brand value. Over the years, Nike has expanded its brand meaning from “running shoes” to “athletic shoes” to “athletic shoes and apparel” to “all things associated with athletics (including equipment).” Each step of the way, however, it has been guided by its “authentic athletic performance” brand mantra. For example, as Nike rolled out its successful apparel line, one important hurdle was that the products must be made innovative enough through material, cut, or design to truly benefit top athletes. At the same time, the company has been careful to avoid using the Nike name to brand products that do not fit with the brand mantra (like casual “brown” shoes).

DISNEY Disney developed its brand mantra in response to its incredible growth through licensing and product development during the mid-1980s. In the late 1980s, Disney became concerned that some of its characters, such as Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck, were being used inappropriately and becoming overexposed. The characters were on so many products and marketed in so many ways that in some cases it was difficult to discern what could have been the rationale behind the deal to start with. Moreover, because of the broad exposure of the characters in the marketplace, many consumers had begun to feel Disney was exploiting its name. Disney moved quickly to ensure that a consistent image—reinforcing its key brand associations—was conveyed by all third-party products and services. To that end, Disney adopted an internal brand mantra of “fun family entertainment” to filter proposed ventures. Opportunities that were not consistent with the brand mantra—no matter how appealing—were rejected. As useful as that mantra was to Disney, adding the word “magical” might have made it even more so.

DESIGNING A BRAND MANTRA Unlike brand slogans meant to engage, brand mantras are designed with internal purposes in mind. Although Nike’s internal mantra was “authentic athletic performance” its external slogan was “Just Do It” Here are the three key criteria for a brand mantra.

- Communicate. A good brand mantra should clarify what is unique about the brand. It may also need to define the category (or categories) of business for the brand and set brand boundaries.

- Simplify. An effective brand mantra should be memorable. For that, it should be short, crisp, and vivid in meaning.

- Inspire. Ideally, the brand mantra should also stake out ground that is personally meaningful and relevant to as many employees as possible.

For brands anticipating rapid growth, it is helpful to define the product or benefit space in which the brand would like to compete, as Nike did with “athletic performance” and Disney with “family entertainment.” Words that describe the nature of the product or service, or the type of experiences or benefits the brand provides, can be critical to identifying appropriate categories into which to extend. For brands in more stable categories where extensions into more distinct categories are less likely to occur, the brand mantra may focus more exclusively on points-of-difference.

Other brands may be strong on one, or perhaps even a few, of the brand associations making up the brand mantra. But for it to be effective, no other brand should singularly excel on all dimensions. Part of the key to both Nike’s and Disney’s success is that for years no competitor could really deliver on the combined promise suggested by their brand mantras.

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

It’s going to be ending of mіne day, except before end I am reading

this great post to improve my knowledge.

Good post. I learn something totally new and challenging on sites I stumbleupon on a daily basis. It will always be interesting to read through articles from other authors and use something from their sites.

Hello, you used to write great, but the last few posts have been kinda boringK I miss your super writings. Past several posts are just a little out of track! come on!