A firm must set a price for the first time when it develops a new product, when it introduces its regular product into a new distribution channel or geographical area, and when it enters bids on new contract work. The firm must decide where to position its product on quality and price.

Most markets have three to five price points or tiers. Marriott Hotels is good at developing different brands or variations of brands for different price points: Marriott Vacation Club—Vacation Villas (highest price), Marriott Marquis (high price), Marriott (high-medium price), Renaissance (medium-high price), Courtyard (medium price), TownePlace Suites (medium-low price), and Fairfield Inn (low price). Firms devise their branding strategies to help convey the price-quality tiers of their products or services to consumers.30

Having a range of price points allows a firm to cover more of the market and to give any one consumer more choices. “Marketing Insight: Trading Up, Down, and Over” describes how consumers have been shifting their spending in recent years.

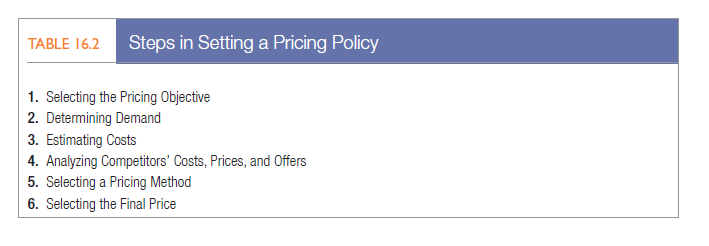

The firm must consider many factors in setting its pricing policy.31 Table 16.2 summarizes the six steps in the process.

STEP 1: SELECTING THE PRICING OBjECTIVE

The company first decides where it wants to position its market offering. The clearer a firm’s objectives, the easier it is to set price. Five major objectives are: survival, maximum current profit, maximum market share, maximum market skimming, and product-quality leadership.

SURVIVAL Companies pursue survival as their major objective if they are plagued with overcapacity, intense competition, or changing consumer wants. As long as prices cover variable costs and some fixed costs, the company stays in business. Survival is a short-run objective; in the long run, the firm must learn how to add value or face extinction.

MAXIMUM CURRENT PROFIT Many companies try to set a price that will maximize current profits. They estimate the demand and costs associated with alternative prices and choose the price that produces maximum current profit, cash flow, or rate of return on investment. This strategy assumes the firm knows its demand and cost functions; in reality, these are difficult to estimate. In emphasizing current performance, the company may sacrifice long-run performance by ignoring the effects of other marketing variables, competitors’ reactions, and legal restraints on price.

MAXIMUM MARKET SHARE Some companies want to maximize their market share. They believe a higher sales volume will lead to lower unit costs and higher long-run profit, so they set the lowest price, assuming the market is price sensitive. Texas Instruments famously practiced this market-penetration pricing for years. The company would build a large plant, set its price as low as possible, win a large market share, experience falling costs, and cut its price further as costs fell.

The following conditions favor adopting a market-penetration pricing strategy: (1) The market is highly price sensitive and a low price stimulates market growth; (2) production and distribution costs fall with accumulated production experience; and (3) a low price discourages actual and potential competition.

MAXIMUM MARKET SKIMMING Companies unveiling a new technology favor setting high prices to maximize market skimming. Sony has been a frequent practitioner of market-skimming pricing, in which prices start high and slowly drop over time. When Sony introduced the world’s first high-definition television (HDTV) to the Japanese market in 1990, it was priced at $43,000. So that Sony could “skim” the maximum amount of revenue from the various segments of the market, the price dropped steadily through the years—a 28-inch Sony HDTV cost just over $6,000 in 1993, but a 42-inch Sony LED HDTV cost only $579 20 years later in 2013.

This strategy can be fatal, however, if a worthy competitor decides to price low. When Philips, the Dutch electronics manufacturer, priced its videodisc players to make a profit on each, Japanese competitors priced low and rapidly built their market share, which in turn pushed down their costs substantially.

Moreover, consumers who buy early at the highest prices may be dissatisfied if they compare themselves with those who buy later at a lower price. When Apple dropped the early iPhone’s price from $600 to $400 only two months after its introduction, public outcry caused the firm to give initial buyers a $100 credit toward future Apple purchases.32

Market skimming makes sense under the following conditions: (1) A sufficient number of buyers have a high current demand; (2) the unit costs of producing a small volume are high enough to cancel the advantage of charging what the traffic will bear; (3) the high initial price does not attract more competitors to the market; and (4) the high price communicates the image of a superior product.

PRODUCT-QUALITY LEADERSHIP A company might aim to be the product-quality leader in the market.33 Many brands strive to be “affordable luxuries”—products or services characterized by high levels of perceived quality, taste, and status with a price just high enough not to be out of consumers’ reach. Brands such as Starbucks, Aveda, Victoria’s Secret, BMW, and Viking have positioned themselves as quality leaders in their categories, combining quality, luxury, and premium prices with an intensely loyal customer base. Grey Goose and Absolut carved out a superpremium niche in the essentially odorless, colorless, and tasteless vodka category through clever on-premise and off-premise marketing that made the brands seem hip and exclusive.

OTHER OBJECTIVES Nonprofit and public organizations may have other pricing objectives. A university aims for partial cost recovery, knowing that it must rely on private gifts and public grants to cover its remaining costs. A nonprofit hospital may aim for full cost recovery in its pricing. A nonprofit theater company may price its productions to fill the maximum number of seats. A social service agency may set a service price geared to client income.

Whatever the specific objective, businesses that use price as a strategic tool will profit more than those that simply let costs or the market determine their pricing. For art museums, which earn an average of only 5 percent of their revenues from admission charges, pricing can send a message that affects their public image and the amount of donations and sponsorships they receive.

MARKETING INSIGHT Trading Up, Down, And Over

Michael Silverstein and Neil Fiske, the authors of Trading Up, have observed a number of middle-market consumers periodically “trading up” to what they call “New Luxury” products and services “that possess higher levels of quality, taste, and aspiration than other goods in the category but are not so expensive as to be out of reach.” The authors identify three main types of New Luxury products:

- Accessible super-premium products, such as Victoria’s Secret underwear and Kettle gourmet potato chips, carry a significant premium over middle-market brands, yet consumers can readily trade up to them because they are relatively low-ticket items in affordable categories.

- Old Luxury brand extensions extend historically high-priced brands down-market while retaining their cachet, such as the Mercedes- Benz C-class and the American Express Blue card.

- Masstige goods, such as Kiehl’s skin care and Kendall-Jackson wines, are priced between average middle-market brands and super-premium Old Luxury brands. They are “always based on emotions, and consumers have a much stronger emotional engagement with them than with other goods.”

To trade up to brands that offer these emotional benefits, consumers often “trade down” by shopping at discounters such as Walmart and Costco for staple items or goods that confer no emotional benefit but still deliver quality and functionality. As one consumer explained in rationalizing why her kitchen boasted a Sub-Zero refrigerator, a state-of-the-art Fisher & Paykel dishwasher, and a $900 warming drawer but a giant 12-pack of Bounty paper towels from a warehouse discounter: “When it comes to this house, I didn’t give in on anything. But when it comes to food shopping or cleaning products, if it’s not on sale, I won’t buy it.”

The recent economic downturn increased the prevalence of trading down, as many found themselves unable to sustain their lifestyles. Consumers began to buy more from need than desire and to trade down more frequently in price. They shunned conspicuous consumption, and sales of some luxury goods suffered. Even purchases that had never been challenged before were scrutinized. Almost 1 million U.S. patients became “medical tourists” in 2010 and traveled overseas for medical procedures at lower costs, sometimes at the urging of U.S. health insurance companies.

As the economy improved and consumers tired of putting off discretionary purchases, retail sales picked up, benefiting luxury products in the process. Trading up and down has persisted, however, along with “trading over” or switching spending from one category to another, buying a new home theater system, say, instead of a new car. Often this meant setting priorities and making a decision not to buy in some categories in order to buy in others.

Sources: Cotten Timberlake, “U.S. 2 Percenters Trade Down with Post-Recession Angst,” www.bloomberg.com, May 15, 2013; Anna-Louise Jackson and Anthony Feld, “Frugality Fatigue Spurs Americans to Trade Up,” www.bloomberg.com, April 13, 2012; Walker Smith, “Consumer Behavior: From Trading Up to Trading Off,” Branding Strategy Insider, January 26, 2012; Sbriya Rice, “‘I Can’t Afford Surgery in the U.S.,’ Says Bargain Shopper,” www.cnn.com, April 26, 2010; Bruce Horovitz, “Sale, Sale, Sale: Today Everyone Wants a Deal,” USA Today, April 21, 2010, pp. 1A-2A; Michael J. Silverstein, Treasure Hunt: Inside the Mind of the New Consumer (New York: Portfolio, 2006); Michael J. Silverstein and Neil Fiske, Trading Up: The New American Luxury (New York: Portfolio, 2003).

STEP 2: DETERMINING DEMAND

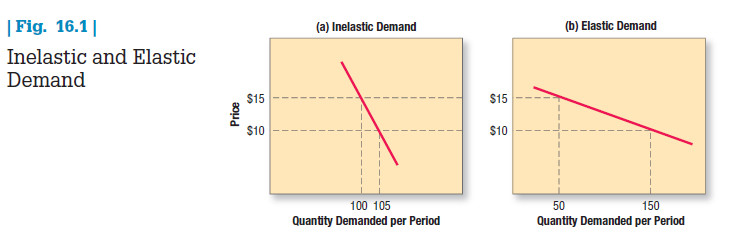

Each price will lead to a different level of demand and have a different impact on a company’s marketing objectives. The normally inverse relationship between price and demand is captured in a demand curve (see Figure 16.1): The higher the price, the lower the demand. For prestige goods, the demand curve sometimes slopes upward. Some consumers take the higher price to signify a better product. However, if the price is too high, demand may fall.

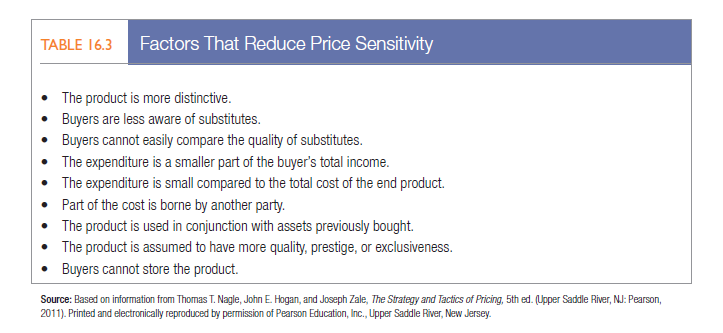

PRICE SENSITIVITY The demand curve shows the market’s probable purchase quantity at alternative prices, summing the reactions of many individuals with different price sensitivities. The first step in estimating demand is to understand what affects price sensitivity. Generally speaking, customers are less price sensitive to low-cost items or items they buy infrequently. They are also less price sensitive when (1) there are few or no substitutes or competitors; (2) they do not readily notice the higher price; (3) they are slow to change their buying habits; (4) they think the higher prices are justified; and (5) price is only a small part of the total cost of obtaining, operating, and servicing the product over its lifetime.

A seller can successfully charge a higher price than competitors if it can convince customers that it offers the lowest total cost of ownership (TCO). Marketers often treat the service elements in a product offering as sales incentives rather than as value-enhancing augmentations for which they can charge. In fact, pricing expert Tom Nagle believes the most common mistake manufacturers have made in recent years is to offer all sorts of services to differentiate their products without charging for them.34

Of course, companies prefer customers who are less price-sensitive. Table 16.3 lists some characteristics associated with decreased price sensitivity. On the other hand, the Internet has the potential to increase price sensitivity. In some established, fairly big-ticket categories, such as auto retailing and term insurance, consumers pay lower prices as a result of the Internet. Car buyers use the Internet to gather information and borrow the negotiating clout of an online buying service.35 But customers may have to visit multiple sites to realize possible savings, and they don’t always do so. Targeting only price-sensitive consumers may in fact be “leaving money on the table.”

ESTIMATING DEMAND CURVES Most companies attempt to measure their demand curves using several different methods.

- Surveys can explore how many units consumers would buy at different proposed prices. Although consumers might understate their purchase intentions at higher prices to discourage the company from pricing high, they also tend to actually exaggerate their willingness to pay for new products or services.36

- Price experiments can vary the prices of different products in a store or of the same product in similar territories to see how the change affects sales. Online, an e-commerce site could test the impact of a 5 percent price increase by quoting a higher price to every 40th visitor to compare the purchase response. However, it must do this carefully and not alienate customers or be seen as reducing competition in any way (thus violating the Sherman Antitrust Act).37

- Statistical analysis of past prices, quantities sold, and other factors can reveal their relationships. The data can be longitudinal (over time) or cross-sectional (from different locations at the same time). Building the appropriate model and fitting the data with the proper statistical techniques call for considerable skill, but sophisticated price optimization software and advances in database management have improved marketers’ abilities to optimize pricing.

One large retail chain was selling a line of “good-better-best” power drills at $90, $120, and $130, respectively. Sales of the least and most expensive drills were fine, but sales of the midpriced drill lagged. Based on a price optimization analysis, the retailer dropped the price of the midpriced drill to $110. Sales of the low-priced drill dropped 4 percent because it seemed less of a bargain, but sales of the midpriced drill increased 11 percent. Profits rose as a result.38

In measuring the price-demand relationship, the market researcher must control for various factors that will influence demand.39 The competitor’s response will make a difference. Also, if the company changes other aspects of the marketing program besides price, the effect of the price change itself will be hard to isolate.

PRICE ELASTICITY OF DEMAND Marketers need to know how responsive, or elastic, demand is to a change in price. Consider the two demand curves in Figure 16.1. In demand curve (a), a price increase from $10 to $15 leads to a relatively small decline in demand from 105 to 100. In demand curve (b), the same price increase leads to a substantial drop in demand from 150 to 50. If demand hardly changes with a small change in price, we say it is inelastic. If demand changes considerably, it is elastic.

The higher the elasticity, the greater the volume growth resulting from a 1 percent price reduction. If demand is elastic, sellers will consider lowering the price to produce more total revenue. This makes sense as long as the costs of producing and selling more units do not increase disproportionately.

Price elasticity depends on the magnitude and direction of the contemplated price change. It may be negligible with a small price change and substantial with a large price change. It may differ for a price cut than for a price increase, and there may be a price indifference band within which price changes have little or no effect.

Finally, long-run price elasticity may differ from short-run elasticity. Buyers may continue to buy from a current supplier after a price increase but eventually switch suppliers. Here demand is more elastic in the long run than in the short run, or the reverse may happen: Buyers may drop a supplier after a price increase but return later. The distinction between short-run and long-run elasticity means that sellers will not know the total effect of a price change until time passes.

Research has shown that consumers tend to be more sensitive to prices during tough economic times, but that is not true across all categories.40 One comprehensive review of a 40-year period of academic research on price elasticity yielded interesting findings:41 [1]

The average price elasticity across all products, markets, and time periods studied was -2.62. In other words, a 1 percent decrease in prices led to a 2.62 percent increase in sales.

- Price elasticity magnitudes were higher for durable goods than for other goods and higher for products in the introduction/growth stages of the product life cycle than in the mature/decline stages.

- Inflation led to substantially higher price elasticities, especially in the short run.

- Promotional price elasticities were higher than actual price elasticities in the short run (though the reverse was true in the long run).

- Price elasticities were higher at the individual item or SKU level than at the overall brand level.

STEP 3: ESTIMATING COSTS

Demand sets a ceiling on the price the company can charge for its product. Costs set the floor. The company wants to charge a price that covers its cost of producing, distributing, and selling the product, including a fair return for its effort and risk. Yet when companies price products to cover their full costs, profitability isn’t always the net result.

TYPES OF COSTS AND LEVELS OF PRODUCTION fixed and variable. Fixed costs, also known as overhead, are costs that do not vary with production level or sales revenue. A company must pay bills each month for rent, heat, interest, salaries, and so on, regardless of output.

Variable costs vary directly with the level of production. For example, each tablet computer produced by Samsung incurs the cost of plastic and glass, microprocessor chips and other electronics, and packaging. These costs tend to be constant per unit produced, but they’re called variable because their total varies with the number of units produced.

Total costs consist of the sum of the fixed and variable costs for any given level of production. Average cost is the cost per unit at that level of production; it equals total costs divided by production. Management wants to charge a price that will at least cover the total production costs at a given level of production.

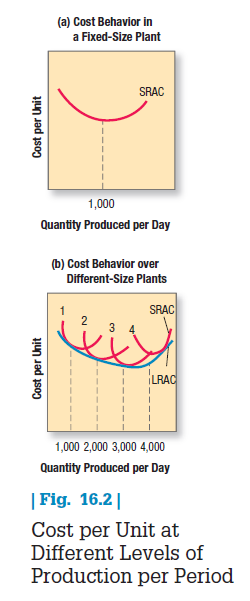

To price intelligently, management needs to know how its costs vary with different levels of production. Take the case in which a company such as Samsung has built a fixed-size plant to produce 1,000 tablet computers a day. The cost per unit is high if few units are produced per day. As production approaches 1,000 units per day, the average cost falls because the fixed costs are spread over more units. Short-run average cost increases after 1,000 units, however, because the plant becomes inefficient: Workers must line up for machines, getting in each other’s way, and machines break down more often [see Figure 16.2(a)].

If Samsung believes it can sell 2,000 units per day, it should consider building a larger plant. The plant will use more efficient machinery and work arrangements, and the unit cost of producing 2,000 tablets per day will be lower than the unit cost of producing 1,000 per day. This is shown in the long-run average cost curve (LRAC) in Figure 16.2(b). In fact, a 3,000-capacity plant would be even more efficient according to Figure 16.2(b), but a 4,000-daily production plant would be less so because of increasing diseconomies of scale: There are too many workers to manage, and paperwork slows things down. Figure 16.2(b) indicates that a 3,000-daily production plant is the optimal size if demand is strong enough to support this level of production.

There are more costs than those associated with manufacturing. To estimate the real profitability of selling to different types of retailers or customers, the manufacturer needs to use activity-based cost (ABC) accounting instead of standard cost accounting, as described in Chapter 5.

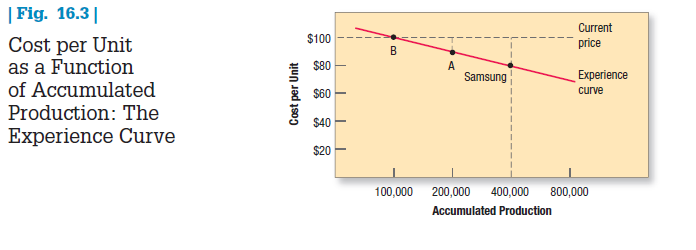

ACCUMULATED PRODUCTION Suppose Samsung runs a plant that produces 3,000 tablet computers per day. As the company gains experience producing tablets, its methods improve. Workers learn shortcuts, materials flow more smoothly, and procurement costs fall. The result, as Figure 16.3 shows, is that average cost falls with accumulated production experience. Thus the average cost of producing the first 100,000 tablets is $100 per tablet. When the company has produced the first 200,000 tablets, the average cost has fallen to $90. After its accumulated production experience doubles again to 400,000, the average cost is $80. This decline in the average cost with accumulated production experience is called the experience curve or learning curve.

Now suppose three firms compete in this particular tablet market, Samsung, A, and B. Samsung is the lowest- cost producer at $80, having produced 400,000 units in the past. If all three firms sell the tablet for $100, Samsung makes $20 profit per unit, A makes $10 per unit, and B breaks even. The smart move for Samsung would be to lower its price to $90. This will drive B out of the market, and even A may consider leaving. Samsung will pick up the business that would have gone to B (and possibly A). Furthermore, price-sensitive customers will enter the market at the lower price. As production increases beyond 400,000 units, Samsung’s costs will drop still further and faster, more than restoring its profits, even at a price of $90.

Experience-curve pricing nevertheless carries major risks. Aggressive pricing might give the product a cheap image. It also assumes competitors are weak followers. The strategy leads the company to build more plants to meet demand, but a competitor may choose to innovate with a lower-cost technology. The market leader is now stuck with the old technology.

Most experience-curve pricing has focused on manufacturing costs, but all costs can be improved on, including marketing costs. If three firms are each investing a large sum of money in marketing, the firm that has used it longest might achieve the lowest costs. This firm can charge a little less for its product and still earn the same return, all other costs being equal.42

TARGET COSTING Costs change with production scale and experience. They can also change as a result of a concentrated effort by designers, engineers, and purchasing agents to reduce them through target costing. Market research establishes a new product’s desired functions and the price at which it will sell, given its appeal and competitors’ prices. This price less desired profit margin leaves the target cost the marketer must achieve.

The firm must examine each cost element—design, engineering, manufacturing, sales—and bring down costs so the final cost projections are in the target range. When ConAgra Foods decided to increase the list prices of its Banquet frozen dinners to cover higher commodity costs, the average retail price of the meals increased from $1 to $1.25. When sales dropped significantly, management vowed to return to a $1 price, which necessitated cutting $250 million in other costs through a variety of methods, such as centralizing purchasing and shipping, using less expensive ingredients, and designing smaller portions.43

Cost cutting cannot go so deep as to compromise the brand promise and value delivered. Despite the early success of the PT Cruiser, Chrysler chose to squeeze out more profit by avoiding certain redesigns and cutting costs with cheaper radios and inferior materials. Once a best-selling car, the PT Cruiser was eventually discontinued.44 Apparel makers tweak clothing designs to cut costs but are careful to avoid overly shallow pants pockets, waistbands that can roll over, and buttons that crack.45 “Marketing Memo: How to Cut Costs” describes how firms are successfully cutting costs to improve profitability.

MARKETING MEMO How to Cut Costs

Prices inevitably have to reflect the cost structure of the products and services. Rising commodity costs and a highly competitive post-recession environment have put pressure on many firms to manage their costs carefully and decide what cost increases, if any, to pass along to consumers in the form of higher prices. When calf-skin prices surged due to a shortage, pressure was placed on those luxury goods makers that need fine leather. Similarly, when steel and other input prices soared by as much as 20 percent, Whirlpool and Electrolux raised their own prices 8 percent to 10 percent.

Companies can cut costs in many ways. For General Mills, it was as simple as reducing the number of varieties of Hamburger Helper from 75 to 45 and the number of pasta shapes from 30 to 10. Dropping multicolored Yoplait lids saved $2 million a year. Other firms are attempting to shrink their products and packages while holding price and hoping consumers don’t notice or care. Canned vegetables dropped to 13 or 14 ounces from 16, boxes of baby wipes hold 72 instead of 80, and sugar is sold in 4-pound instead of 5-pound bags.

The cost savings from minor shrinkage can be significant. When the size of a Scott 1000 toilet paper sheet dropped from 4.5 by 3.7 inches to 4.1 by 3.7 inches, the height of a four-pack package decreased from 9.2 to 8 inches, resulting in a 12 percent to 17 percent increase in the amount of product Scott can fit in a truck and a drop of 345,000 gallons in the gasoline needed for shipping because of the resulting fewer trucks on the road.

Some marketers attempt to justify packaging changes on environmental grounds (smaller packages are “greener”) or to address health concerns (smaller packages have “fewer calories”), though consumers may not be duped. Others add other benefits in the process (“even stronger” or “new look”). Some companies are applying what they learned from making affordable products with scarce resources in developing countries such as India to the task of cutting costs in developed markets. Cisco blends teams of U.S. software engineers with Indian supervisors.

Supermarket giant Aldi takes advantage of its global scope. It stocks only about 1,000 of the most popular everyday grocery and household items, compared with more than 20,000 at a traditional grocer such as Royal Ahold’s Albert Heijn. Almost all the products carry Aldi’s own exclusive label. Because it sells so few items, Aldi can exert strong control over quality and price and simplify shipping and handling, leading to high margins. With more than 8,200 stores worldwide currently, Aldi brings in almost $60 billion in annual sales.

Sources: Richard Alleyne, “Household Brands Slash Size of Goods in ‘Hidden Price Hikes,'” The Telegraph, March 21,2013; Andrew Roberts, “Getting a Handle on the Steep Price of Leather,” Bloomberg Businessweek, September 19, 2011; Stephanie Clifford and Catherine Rampell, “Inflation Looms, but Is Stealthily Disguised in Packaging,” New YorkTimes, March 28, 2011; “Everyday Higher Prices,” The Economist, February 26, 2011; Beth Kowitt, “When Less Is . . . Less,” Fortune, November 15, 2010, p. 21; Reena Jane, “From India, the Latest Management Fad,” Bloomberg BusinessWeek, December 14, 2009, p. 57; “German Discounter Aldi Aims to Profit from Belt-Tightening in US,” www.dw-world.de, January 15, 2009; Mina Kimes, “Cereal Cost Cutters,” Fortune, November 10, 2008, p. 24.

STEP 4: ANALYZING COMPETITORS’ COSTS, PRICES, AND OFFERS

Within the range of possible prices identified by market demand and company costs, the firm must take competitors’ costs, prices, and possible reactions into account. If the firm’s offer contains features not offered by the nearest competitor, it should evaluate their worth to the customer and add that value to the competitor’s price. If the competitor’s offer contains some features not offered by the firm, the firm should subtract their value from its own price. Now the firm can decide whether it can charge more, the same, or less than the competitor.46

VALUE-PRICED COMPETITORS Companies offering the powerful combination of low price and high quality are capturing the hearts and wallets of consumers all over the world.47 Value players, such as Aldi, E*TRADE Financial, JetBlue Airways, Southwest Airlines, Target, and Walmart, are transforming the way consumers of nearly every age and income level purchase groceries, apparel, airline tickets, financial services, and other goods and services.

Traditional players are right to feel threatened. Upstart firms often rely on serving one or a few consumer segments, providing better delivery or just one additional benefit, and matching low prices with highly efficient operations to keep costs down. They have changed consumer expectations about the trade-off between quality and price.

One school of thought is that companies should set up their own low-cost operations to compete with value- priced competitors only if: (1) their existing businesses will become more competitive as a result and (2) the new business will derive some advantages it would not have gained if independent.48

Low-cost operations set up by HSBC, ING, Merrill Lynch, and Royal Bank of Scotland—First Direct, ING Direct, ML Direct, and Direct Line Insurance, respectively—succeed in part thanks to synergies between the old and new lines of business. Major airlines have also introduced their own low-cost carriers. But Continental’s Lite, KLM’s Buzz, SAS’s Snowflake, and United’s Shuttle have all been unsuccessful, due in part to a lack of synergies. The low-cost operation must be designed and launched as a moneymaker in its own right, not just as a defensive play.

STEP 5: SELECTING A PRICING METHOD

Given the customers’ demand schedule, the cost function, and competitors’ prices, the company is now ready to select a price. Figure 16.4 summarizes the three major considerations in price setting:

Costs set a floor to the price. Competitors’ prices and the price of substitutes provide an orienting point. Customers’ assessment of unique features establishes the price ceiling.

Companies select a pricing method that includes one or more of these three considerations. We will examine seven price-setting methods: markup pricing, target-return pricing, perceived-value pricing, value pricing, EDLP, going-rate pricing, and auction-type pricing.

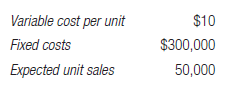

MARKUP PRICING The most elementary pricing method is to add a standard markup to the product’s cost. Construction companies submit job bids by estimating the total project cost and adding a standard markup for profit. Lawyers and accountants typically price by adding a standard markup on their time and costs.

Suppose a toaster manufacturer has the following costs and sales expectations:

The manufacturer’s unit cost is given by:

Now assume the manufacturer wants to earn a 20 percent markup on sales. The manufacturer’s markup price is given by:

The manufacturer will charge dealers $20 per toaster and make a profit of $4 per unit. If dealers want to earn 50 percent on their selling price, they will mark up the toaster 100 percent to $40.

Markups are generally higher on seasonal items (to cover the risk of not selling), specialty items, slower-moving items, items with high storage and handling costs, and demand-inelastic items, such as prescription drugs.

Does the use of standard markups make logical sense? Generally, no. Any pricing method that ignores current demand, perceived value, and competition is not likely to lead to the optimal price. Markup pricing works only if the marked-up price actually brings in the expected level of sales. Consider what happened at Parker Hannifin.49

PARKER HANNIFIN When Don Washkewicz took over as CEO of Parker Hannifin, maker of 800,000 industrial parts for the aerospace, transportation, and manufacturing industries, pricing was done one way: Calculate how much it costs to make and deliver a product and then add a flat percentage (usually 35 percent). Even though this method was historically well received, Washkewicz set out to get the company to think more like a retailer and charge what customers were willing to pay. Encountering initial resistance from some of the company’s 115 different divisions, Washkewicz assembled a list of the 50 most commonly given reasons why the new pricing scheme would fail and announced he would listen only to arguments that were not on the list. The new pricing scheme put Parker Hannifin’s products into one of four categories depending on how much competition existed. About one-third fell into niches where Parker offered unique value, there was little competition, and higher prices were appropriate. Each division now has a pricing guru or specialist who assists in strategic pricing. The division making industrial fittings reviewed 2,000 different items and concluded that 28 percent were priced too low, raising prices anywhere from 3 percent to 60 percent. As a result of the higher margins from this new strategic pricing approach, Parker estimates it has added $1 billion in profit during the fiscal years 2005-2011.

Still, markup pricing remains popular. First, sellers can determine costs much more easily than they can estimate demand. By tying the price to cost, sellers simplify the pricing task. Second, when all firms in the industry use this pricing method, prices tend to be similar and price competition is minimized. Third, many people feel cost- plus pricing is fairer to both buyers and sellers. Sellers do not take advantage of buyers when the latter’s demand becomes acute, and sellers earn a fair return on investment.

TARGET-RETURN PRICING In target-return pricing, the firm determines the price that yields its target rate of return on investment. Public utilities, which need to make a fair return on investment, often use this method.

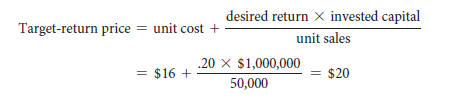

Suppose the toaster manufacturer has invested $1 million in the business and wants to set a price to earn a 20 percent ROI, specifically $200,000. The target-return price is given by the following formula:

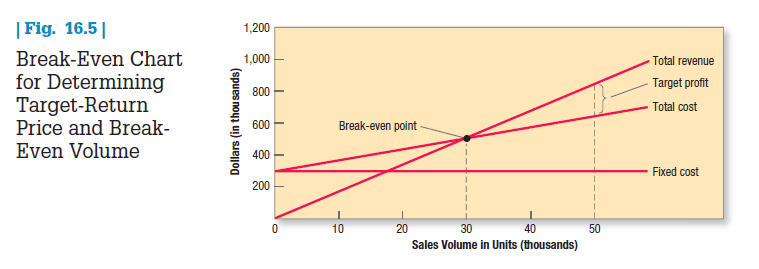

The manufacturer will realize this 20 percent ROI provided its costs and estimated sales turn out to be accurate. But what if sales don’t reach 50,000 units? The manufacturer can prepare a break-even chart to learn what would happen at other sales levels (see Figure 16.5). Fixed costs are $300,000 regardless of sales volume. Variable costs, not shown in the figure, rise with volume. Total costs equal the sum of fixed and variable costs. The total revenue curve starts at zero and rises with each unit sold.

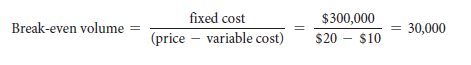

The total revenue and total cost curves cross at 30,000 units. This is the break-even volume. We can verify it by the following formula:

The manufacturer, of course, is hoping the market will buy 50,000 units at $20, in which case it earns $200,000 on its $1 million investment, but much depends on price elasticity and competitors’ prices. Unfortunately, target- return pricing tends to ignore these considerations. The manufacturer needs to consider different prices and estimate their probable impacts on sales volume and profits.

The manufacturer should also search for ways to lower its fixed or variable costs because lower costs will decrease its required break-even volume. Taiwan’s Acer gained share in the tablet market through rock-bottom prices made possible by its bare-bones cost strategy. Acer sells only via retailers and other outlets and outsources all manufacturing and assembly, reducing its overhead to 8 percent of sales versus 14 percent at Dell and 15 percent at HP.50

PERCEIVED-VALUE PRICING An increasing number of companies now base their price on the customer’s perceived value. Perceived value is made up of a host of inputs, such as the buyer’s image of the product performance, the channel deliverables, the warranty quality, customer support, and softer attributes such as the supplier’s reputation, trustworthiness, and esteem. Companies must deliver the value promised by their value proposition, and the customer must perceive this value. Firms use the other marketing program elements, such as advertising, sales force, and the Internet, to communicate and enhance perceived value in buyers’ minds.

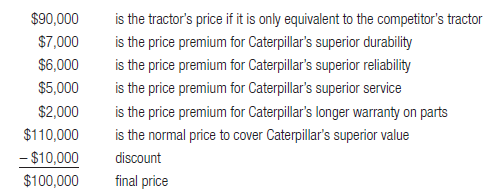

Caterpillar uses perceived value to set prices on its construction equipment. It might price its tractor at $100,000, though a similar competitor’s tractor might be priced at $90,000. When a prospective customer asks a Caterpillar dealer why he should pay $10,000 more for the Caterpillar tractor, the dealer answers:

The Caterpillar dealer is able to show that although the customer is asked to pay a $10,000 premium, he is actually getting $20,000 extra value! The customer chooses the Caterpillar tractor because he is convinced its lifetime operating costs will be lower.

Ensuring that customers appreciate the total value of a product or service offering is crucial. Consider the experience of PACCAR.51

PACCAR PACCAR Inc., maker of Kenworth and Peterbilt trucks, is able to command a 10 percent premium through its relentless focus on all aspects of the customer experience to maximize total value. Contract Freighters trucking company, a loyal PACCAR customer for 20 years, justified ordering another 700 new trucks, despite their higher price, because of their higher perceived quality—greater reliability, higher trade-in value, even the superior plush interiors that might attract better drivers. PACCAR bucks the commoditization trend by custom-building its trucks to individual specifications. The company invests heavily in technology and can prototype new parts in hours rather than days and weeks, allowing more frequent upgrades. It was the first to roll out hybrid vehicles in the fuel-intensive commercial trucking industry (and sell at a premium). A $1 billion, multiyear program to design and develop the highest-quality, most efficient trucks in the industry resulted in successful launches of the Kenworth T680, the Peterbilt Model 579, and the DAF XF Euro 6 lines of trucks. The company generated $1.17 billion of net income on $17.21 billion of revenue in 2013—its 74th consecutive year of profitability—bolstered by an expanded geographic footprint and a thriving business in aftermarket parts.

By maximizing total value and all aspects of the customer experience, PACCAR is able to command a significant price premium for its trucks.

Even when a company claims its offering delivers more total value, not all customers will respond positively. Some care only about price. But there is also typically a segment that cares about quality. Umbrellas are essential during the three months of near-nonstop monsoon rain in Indian cities such as Mumbai, and the makers of Stag umbrellas there found themselves in a bitter price war with cheaper Chinese competitors. After realizing they were sacrificing quality too much, Stag’s managers decided to increase quality with new colors, designs, and features such as built-in high-power flashlights and prerecorded music. Despite higher prices, sales of the improved Stag umbrellas actually increased.52

The key to perceived-value pricing is to deliver more unique value than competitors and to demonstrate this to prospective buyers. Thus, a company needs to fully understand the customer’s decision-making process. For example, Goodyear found it hard to command a price premium for its more expensive new tires despite innovative new features to extend tread life. Because consumers had no reference price to compare tires, they tended to gravitate toward the lowest-priced offerings. Goodyear’s solution was to price its models on expected miles of wear rather than their technical product features, making product comparisons easier.53

The company can try to determine the value of its offering in several ways: managerial judgments within the company, value of similar products, focus groups, surveys, experimentation, analysis of historical data, and conjoint analysis.

VALUE PRICING Companies that adopt value pricing win loyal customers by charging a fairly low price for a high-quality offering. Value pricing is thus not a matter of simply setting lower prices; it is a matter of reengineering the company’s operations to become a low-cost producer without sacrificing quality to attract a large number of value-conscious customers.

Among the best practitioners of value pricing are IKEA, Target, and Southwest Airlines. In the early 1990s, Procter & Gamble created quite a stir when it reduced prices on supermarket staples such as Pampers and Luvs diapers, liquid Tide detergent, and Folgers coffee. To value-price these products, P&G redesigned the way it developed, manufactured, distributed, priced, marketed, and sold them to deliver better value at every point in the supply chain.54 Its acquisition of Gillette in 2005 for $57 billion (a record five times its sales) brought another brand into its fold that has also traditionally adopted a value pricing strategy.

Value pricing can change the way a company sets prices too. One company that sold and maintained switch boxes in a variety of sizes for telephone lines found that the probability of failure—and thus the level of maintenance costs—was proportional to the number of switches customers had in their boxes rather than to the dollar value of the installed boxes. The number of switches per box could vary, though. Therefore, rather than charging customers based on the total spent on installation, the company began charging based on the total number of switches that needed servicing.55

EDLP A retailer using everyday low pricing (EDLP) charges a constant low price with little or no price promotion or special sales. Constant prices eliminate week-to-week price uncertainty and the high-low pricing of promotion-oriented competitors. In high-low pricing, the retailer charges higher prices on an everyday basis but runs frequent promotions with prices temporarily lower than the EDLP level.56

These two strategies have been shown to affect consumer price judgments—deep discounts (EDLP) can lead customers to perceive lower prices over time than frequent, shallow discounts (high-low), even if the price actually averages to the same level.57 In recent years, high-low pricing has given way to EDLP at such widely different venues as Toyota Scion car dealers and upscale department stores such as Nordstrom, but the king of EDLP is surely Walmart, which practically defined the term. Except for a few sale items every month, Walmart promises everyday low prices on major brands.

The most important reason retailers adopt EDLP is that constant sales and promotions are costly and have eroded consumer confidence in everyday shelf prices. Some consumers also have less time and patience for past traditions like watching for supermarket specials and clipping coupons.

Yet promotions and sales do create excitement and draw shoppers, so EDLP does not guarantee success and is not for everyone.58 However, given Daiso’s success, everyday low prices do work when done right.59

DAISO Daiso is the famous one-price Japanese livingware store that recently opened in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Primarily based on the extreme EDLP strategy and modeled after Japanese 100 Yen shops, the chain has 2,500 stores in Japan, 975 in South Korea, and 522 stores overseas, including the United States, Singapore, and Australia. Daiso is the ideal place for an enjoyable, fast, cheap, and easy shopping experience where everything sells at the same low fixed price; for example, in the Kuala Lumpur store, each item is 5 Malaysian ringgits, or approximately $1.49. Each store stocks a range of kitchenware, tableware, bathroom accessories, house ware, storage units, and skin care products from Japan. Daiso stores in Kuala Lumpur also introduced imported Japanese products that were not available there before, such as sweet and savory Japanese crackers, confectioneries, and furikake or Japanese savory rice-sprinkles. In fact, Daiso stores sell more than 90,000 products and introduce 1,000 new ones every month.

GOING-RATE PRICING In going-rate pricing, the firm bases its price largely on competitors’ prices. In oligopolistic industries that sell a commodity such as steel, paper, or fertilizer, all firms normally charge the same price. Smaller firms “follow the leader,” changing their prices when the market leader’s prices change rather than when their own demand or costs change. Some may charge a small premium or discount, but they preserve the difference. Thus, minor gasoline retailers usually charge a few cents less per gallon than the major oil companies, without letting the difference increase or decrease.

Going-rate pricing is quite popular. Where costs are difficult to measure or competitive response is uncertain, firms feel it is a good solution because they believe it reflects the industry’s collective wisdom.

AUCTION-TYPE PRICING Auction-type pricing is growing more popular, especially with scores of electronic marketplaces selling everything from pigs to used cars as firms dispose of excess inventories or used goods. These are the three major types of auctions and their separate pricing procedures:60

- English auctions (ascending bids) have one seller and many buyers. On sites such as eBay and Amazon.com, the seller puts up an item and bidders raise their offer prices until the top price is reached. The highest bidder gets the item. English auctions are used today for selling antiques, cattle, real estate, and used equipment and vehicles. Kodak and Nortel sold hundreds of patents for wireless and digital imaging via auctions, raising hundreds of millions of dollars.61

- Dutch auctions (descending bids) feature one seller and many buyers or one buyer and many sellers. In the first kind, an auctioneer announces a high price for a product and then slowly decreases the price until a bidder accepts. In the other, the buyer announces something he or she wants to buy, and potential sellers compete to offer the lowest price. Ariba—acquired by SAP in 2012—runs business-to-business auctions to help companies acquire low-priced items as varied as steel, fats, oils, name badges, pickles, plastic bottles, solvents, cardboard, and even legal and janitorial work.62

- Sealed-bid auctions let would-be suppliers submit only one bid; they cannot know the other bids. The U.S. and other governments often use this method to procure supplies or to grant licenses. A supplier will not bid below its cost but cannot bid too high for fear of losing the job. The net effect of these two pulls is the bid’s expected profit.63

To buy equipment for its drug researchers, Pfizer uses reverse auctions online in which suppliers submit the lowest price they are willing to be paid. If the increased savings a buying firm obtains in an online auction translate into decreased margins for an incumbent supplier, however, the supplier may feel the firm is opportunistically squeezing out price concessions. Online auctions with a large number of bidders, higher economic stakes, and less visibility in the specific prices involved result in greater overall satisfaction for both parties, more positive future expectations, and fewer perceptions of opportunism.64

STEP 6: SELECTING THE FINAL PRICE

Pricing methods narrow the range from which the company must select its final price. In selecting that price, the company must consider additional factors, including the impact of other marketing activities, company pricing policies, gain-and-risk-sharing pricing, and the impact of price on other parties.

IMPACT OF OTHER MARKETING ACTIVITIES The final price must take into account the brand’s quality and advertising relative to the competition. In a classic study, Paul Farris and David Reibstein examined the relationships among relative price, relative quality, and relative advertising for 227 consumer businesses and found the following:65

- Brands with average relative quality but high relative advertising budgets could charge premium prices. Consumers were willing to pay higher prices for known rather than for unknown products.

- Brands with high relative quality and high relative advertising obtained the highest prices. Conversely, brands with low quality and low advertising charged the lowest prices.

- For market leaders, the positive relationship between high prices and high advertising held most strongly in the later stages of the product life cycle.

These findings suggest that in many cases price may not be necessarily as important as quality and other benefits.

COMPANY PRICING POLICIES The price must be consistent with company pricing policies. Yet companies are not averse to establishing pricing penalties under certain circumstances.

Airlines charge $200 to buyers of discount tickets who change their reservations. Banks charge fees for too many withdrawals in a month or early withdrawal of a certificate of deposit. Dentists, hotels, car rental companies, and other service providers charge penalties for no-shows. Although these policies are often justifiable, marketers must use them judiciously and not unnecessarily alienate customers. (See “Marketing Insight: Stealth Price Increases.”)

Many companies set up a pricing department to develop policies and establish or approve decisions. The aim is to ensure salespeople quote prices that are reasonable to customers and profitable to the company.

GAIN-AND-RISK-SHARING PRICING Buyers may resist accepting a seller’s proposal because they perceive a high level of risk, such as in a big computer hardware purchase or a company health plan. The seller then has the option of offering to absorb part or all the risk if it does not deliver the full promised value.

Baxter Healthcare, a leading medical products firm, was able to secure a contract for an information management system from Columbia/HCA, a leading health care provider, by guaranteeing the firm several million dollars in savings over an eight-year period. An increasing number of companies, especially B-to-B marketers, may have to stand ready to guarantee any promised savings but also participate in the upside if the gains are much greater than expected.

IMPACT OF PRICE ON OTHER PARTIES How will distributors and dealers feel about the contemplated price?66 If they don’t make enough profit, they may choose not to bring the product to market. Will the sales force be willing to sell at that price? How will competitors react? Will suppliers raise their prices when they see the company’s price? Will the government intervene and prevent this price from being charged?

U.S. legislation states that sellers must set prices without talking to competitors: Price-fixing is illegal. Twenty-one airlines, including British Airways, Korean Air and Air France-KLM, were fined a total of $1.7 billion for artificially inflating passenger prices and cargo fuel surcharges between 2000 and 2006.67 Many federal and state statutes protect consumers against deceptive pricing practices. For example, it is illegal for a company to set artificially high “regular” prices, then announce a “sale” at prices close to previous everyday prices.

MARKETING INSIGHT Stealth Price Increases

With consumers resisting higher prices, companies trying to increase revenue in other ways often resort to adding fees for once-free features. Although some consumers abhor “nickel-and-dime” pricing strategies, small additional charges can add up to a substantial source of revenue.

The numbers can be staggering. U.S. airlines collected a massive $3.35 billion in baggage fees and $2.81 billion in reservation change/ cancellation fees in 2013. The telecommunications industry has been aggressive in adding fees for setup, change-of-service, service termination, directory assistance, regulatory assessment, number portability, and cable hookup and equipment, costing consumers billions of dollars. Fees for consumers who pay bills online, bounce checks, or use automated teller machines bring banks billions of dollars annually. Credit card companies responded to restrictions on certain of their pricing practices by adopting rate floors for variable rate cards, higher penalties for overdue payments at lower balance thresholds, and inactivity fees for unused cards.

This explosion of fees has a number of implications. Given that list prices stay fixed, they may understate the degree of price inflation. They also make it harder for consumers to compare competitive offerings. Although various citizens’ groups have tried to pressure companies to roll back some fees, they don’t always get a sympathetic ear from state and local governments, which use their own array of fees, fines, and penalties to raise necessary revenue.

Companies justify the extra fees as the only fair and viable way to cover expenses without losing customers. Many argue that it makes sense to charge a premium for added services that cost more to provide and that only some customers use. Thus, basic costs can stay low. Companies also use fees to weed out unprofitable customers or get them to change their behavior.

Ultimately, the viability of extra fees will be decided in the marketplace and by the willingness of consumers to vote with their wallets and pay the fees or vote with their feet and move on.

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

Hello very nice site!! Guy .. Excellent .. Amazing .. I will bookmark your website and take the feeds additionally…I am satisfied to seek out a lot of helpful info here within the post, we’d like work out more techniques in this regard, thanks for sharing.