Several methods can be used to collect primary data. The choice of a method depends upon the purpose of the study, the resources available and the skills of the researcher. There are times when the method most appropriate to achieve the objectives of a study cannot be used because of constraints such as a lack of resources and/or required skills. In such situations you should be aware of the problems that these limitations impose on the quality of the data.

In selecting a method of data collection, the socioeconomic-demographic characteristics of the study population play an important role: you should know as much as possible about characteristics such as educational level, age structure, socioeconomic status and ethnic background. If possible, it is helpful to know the study population’s interest in, and attitude towards, participation in the study. Some populations, for a number of reasons, may not feel either at ease with a particular method of data collection (such as being interviewed) or comfortable with expressing opinions in a questionnaire. Furthermore, people with little education may respond differently to certain methods of data collection compared with people with more education.

Another important determinant of the quality of your data is the way the purpose and relevance of the study are explained to potential respondents. Whatever method of data collection is used, make sure that respondents clearly understand the purpose and relevance of the study. This is particularly important when you use a questionnaire to collect data, because in an interview situation you can answer a respondent’s questions but in a questionnaire you will not have this opportunity.

In the following sections each method of data collection is discussed from the point of view of its applicability and suitability to a situation, and the problems and limitations associated with it.

1. Observation

Observation is one way to collect primary data. Observation is a purposeful, systematic and selective way of watching and listening to an interaction or phenomenon as it takes place. There are many situations in which observation is the most appropriate method of data collection; for example, when you want to learn about the interaction in a group, study the dietary patterns of a population, ascertain the functions performed by a worker, or study the behaviour or personality traits of an individual. It is also appropriate in situations where full and/ or accurate information cannot be elicited by questioning, because respondents either are not co-operative or are unaware of the answers because it is difficult for them to detach themselves from the interaction. In summary, when you are more interested in the behaviour than in the perceptions of individuals, or when subjects are so involved in the interaction that they are unable to provide objective information about it, observation is the best approach to collect the required information.

1.1. Types of observation

There are two types of observation:

- participant observation;

- non-participant observation.

Participant observation is when you, as a researcher, participate in the activities of the group being observed in the same manner as its members, with or without their knowing that they are being observed. For example, you might want to examine the reactions of the general population towards people in wheelchairs. You can study their reactions by sitting in a wheelchair yourself. Or you might want to study the life of prisoners and pretend to be a prisoner in order to do this.

Non-participant observation, on the other hand, is when you, as a researcher, do not get involved in the activities of the group but remain a passive observer, watching and listening to its activities and drawing conclusions from this. For example, you might want to study the functions carried out by nurses in a hospital. As an observer, you could watch, follow and record the activities as they are performed. After making a number of observations, conclusions could be drawn about the functions nurses carry out in the hospital. Any occupational group in any setting can be observed in the same manner.

1.2. Problems with using observation as a method of data collection

The use of observation as a method of data collection may suffer from a number of problems, which is not to suggest that all or any of these necessarily prevail in every situation. But as a beginner you should be aware of these potential problems:

- When individuals or groups become aware that they are being observed, they may change their behaviour. Depending upon the situation, this change could be positive or negative – it may increase or decrease, for example, their productivity – and may occur for a number of reasons. When a change in the behaviour of persons or groups is attributed to their being observed it is known as the Hawthorne effect. The use of observation in such a situation may introduce distortion: what is observed may not represent their normal behaviour.

- There is always the possibility of observer bias. if an observer is not impartial, s/he can easily introduce bias and there is no easy way to verify the observations and the inferences drawn from them.

- The interpretations drawn from observations may vary from observer to observer.

- There is the possibility of incomplete observation and/or recording, which varies with the method of recording. An observer may watch keenly but at the expense of detailed recording. The opposite problem may occur when the observer takes detailed notes but in doing so misses some of the interaction.

1.3. Situations in which observations can be made

Observations can be made under two conditions:

- natural;

- controlled.

Observing a group in its natural operation rather than intervening in its activities is classified as observation under natural conditions. Introducing a stimulus to the group for it to react to and observing the reaction is called controlled observation.

1.4. Recording observations

There are many ways of recording observations. The selection of a method of recording depends upon the purpose of the observation. The way an observation is recorded also determines whether it is a quantitative or qualitative study. Narrative and descriptive recording is mainly used in qualitative research but if you are doing a quantitative study you would record an observation in categorical form or on a numerical scale. Keep in mind that each method of recording an observation has its advantages and disadvantages:

- Narrative recording – In this form of recording the researcher records a description of the interaction in his/her own words. Such a type of recording clearly falls in the domain of qualitative research. usually, a researcher makes brief notes while observing the interaction and then soon after completing the observation makes detailed notes in narrative form. in addition, some researchers may interpret the interaction and draw conclusions from it. The biggest advantage of narrative recording is that it provides a deeper insight into the interaction. however, a disadvantage is that an observer may be biased in his/her observation and, therefore, the interpretations and conclusions drawn from the observation may also be biased. in addition, interpretations and conclusions drawn are bound to be subjective reflecting the researcher’s perspectives. Also, if a researcher’s attention is on observing, s/he might forget to record an important piece of interaction and, obviously, in the process of recording, part of the interaction may be missed. hence, there is always the possibility of incomplete recording and/or observation. in addition, when there are different observers the comparability of narrative recording can be a problem.

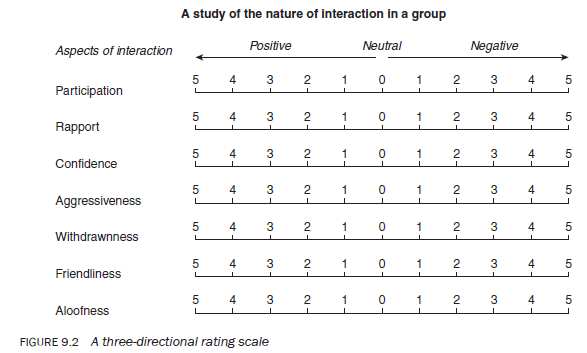

- Using scales – At times some observers may prefer to develop a scale in order to rate various aspects of the interaction or phenomenon. The recording is done on a scale developed by the observer/researcher. A scale may be one-, two- or three-directional, depending upon the purpose of the observation. For example, in the scale in Figure 9.2 – designed to record the nature of the interaction within a group – there are three directions: positive, negative and neutral.

The main advantage of using scales in recording observation is that you do not need to spend time on taking detailed notes and can thus concentrate on observation. On the other hand, the problems with using a scale are that it does not provide specific and in-depth information about the interaction. In addition, it may suffer from any of the following errors:

-

- Unless the observer is extremely confident of his/her ability to assess an interaction, s/he may tend to avoid the extreme positions on the scale, using mostly the central part. The error that this tendency creates is called the error of central tendency.

- Some observers may prefer certain sections of the scale in the same way that some teachers are strict markers and others are not. When observers have a tendency to use a particular part of the scale in recording an interaction, this phenomenon is known as the elevation effect.

-

- another type of error that may be introduced is when the way an observer rates an individual on one aspect of the interaction influences the way s/he rates that individual on another aspect of the interaction. again something similar to this can happen in teaching when a teacher’s assessment of the performance of a student in one subject may influence his/her rating of that student’s performance in another. This type of effect is known as the halo effect.

- Categorical recording – Sometimes an observer may decide to record his/her observation using categories. The type and number of categories depend upon the type of interaction and the observer’s choice about how to classify the observation. For example, passive/active (two categories); introvert/extrovert (two categories); always/sometimes/never (three categories); strongly agree/agree/uncertain/disagree/strongly disagree (five categories). The use of categories to record an observation may suffer from the same problems as those associated with scales.

- Recording on electronic devices – Observation can also be recorded on videotape or other electronic devices and then analysed. The advantage of recording an interaction in this way is that the observer can see it a number of times before interpreting an interaction or drawing any conclusions from it and can also invite other professionals to view the interaction in order to arrive at more objective conclusions. However, one of the disadvantages is that some people may feel uncomfortable or may behave differently before a camera. Therefore the interaction may not be a true reflection of the situation.

The choice of a particular method for recording your observation is dependent upon the purpose of the observation, the complexity of the interaction and the type of population being observed. It is important to consider these factors before deciding upon the method for recording your observation.

2. The interview

Interviewing is a commonly used method of collecting information from people. In many walks of life we collect information through different forms of interaction with others. There are many definitions of interviews. According to Monette et al. (1986: 156), ‘an interview involves an interviewer reading questions to respondents and recording their answers’. According to Burns (1997: 329), ‘an interview is a verbal interchange, often face to face, though the telephone may be used, in which an interviewer tries to elicit information, beliefs or opinions from another person’. Any person-to-person interaction, either face to face or otherwise, between two or more individuals with a specific purpose in mind is called an interview.

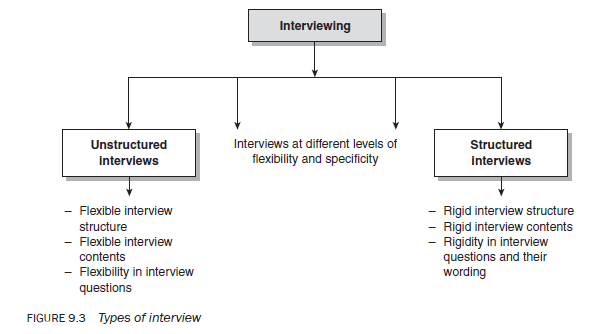

When interviewing a respondent, you, as a researcher, have the freedom to decide the format and content of questions to be asked of your respondents, select the wording of your questions, decide the way you want to ask them and choose the order in which they are to be asked. This process of asking questions can be either very flexible, where you as the interviewer have the freedom to think about and formulate questions as they come to your mind around the issue being investigated, or inflexible, where you have to keep strictly to the questions decided beforehand — including their wording, sequence and the manner in which they are asked. Interviews are classified into different categories according to this degree of flexibility as in Figure 9.3.

2.1. Unstructured Interviews

The strength of unstructured interviews is the almost complete freedom they provide in terms of content and structure.You are free to order these in whatever sequence you wish. You also have complete freedom in terms of the wording you use and the way you explain questions to your respondents. You may formulate questions and raise issues on the spur of the moment, depending upon what occurs to you in the context of the discussion.

Unstructured interviews are prevalent in both quantitative and qualitative research. The difference is in how information obtained through them in response to your questions is likely to be used. In quantitative research you develop response categorisations from responses which are then coded and quantified. In qualitative research the responses are used as descriptors, often in verbatim form, and can be integrated with your arguments, flow of writing and sequence of logic. As unstructured interviews are dominantly used in qualitative research, they are described in greater detail under ‘Methods of data collection in qualitative research’ later in this chapter.

2.2. Structured interviews

In a structured interview the researcher asks a predetermined set of questions, using the same wording and order of questions as specified in the interview schedule. An interview schedule is a written list of questions, open ended or closed, prepared for use by an interviewer in a person-to-person interaction (this may be face to face, by telephone or by other electronic media). Note that an interview schedule is a research tool/instrument for collecting data, whereas interviewing is a method of data collection.

One of the main advantages of the structured interview is that it provides uniform information, which assures the comparability of data. Structured interviewing requires fewer interviewing skills than does unstructured interviewing.

3. The questionnaire

A questionnaire is a written list of questions, the answers to which are recorded by respondents. In a questionnaire respondents read the questions, interpret what is expected and then write down the answers. The only difference between an interview schedule and a questionnaire is that in the former it is the interviewer who asks the questions (and if necessary, explains them) and records the respondent’s replies on an interview schedule, and in the latter replies are recorded by the respondents themselves. This distinction is important in accounting for the respective strengths and weaknesses of the two methods.

In the case of a questionnaire, as there is no one to explain the meaning of questions to respondents, it is important that the questions are clear and easy to understand. Also, the layout of a questionnaire should be such that it is easy to read and pleasant to the eye, and the sequence of questions should be easy to follow. A questionnaire should be developed in an interactive style. This means respondents should feel as if someone is talking to them. In a questionnaire, a sensitive question or a question that respondents may feel hesitant about answering should be prefaced by an interactive statement explaining the relevance of the question. It is a good idea to use a different font for these statements to distinguish them from the actual questions. Examples in Figures 9.4 and 9.5 taken from two surveys recently carried out by the author with the help of two students explain some of the above points.

3.1. Ways of administering a questionnaire

A questionnaire can be administered in different ways.

- The mailed questionnaire – The most common approach to collecting information is to send the questionnaire to prospective respondents by mail. Obviously this approach presupposes that you have access to their addresses. usually it is a good idea to send a prepaid, self-addressed envelope with the questionnaire as this might increase the response rate. a mailed questionnaire must be accompanied by a covering letter (see below for details). One of the major problems with this method is the low response rate. in the case of an extremely low response rate, the findings have very limited applicability to the population studied.

- Collective administration – One of the best ways of administering a questionnaire is to obtain a captive audience such as students in a classroom, people attending a function, participants in a programme or people assembled in one place. This ensures a very high response rate as you will find few people refuse to participate in your study. Also, as you have personal contact with the study population, you can explain the purpose, relevance and

importance of the study and can clarify any questions that respondents may have. The author’s advice is that if you have a captive audience for your study, don’t miss the opportunity – it is the quickest way of collecting data, ensures a very high response rate and saves you money on postage. - Administration in a public place – Sometimes you can administer a questionnaire in a public place such as a shopping centre, health centre, hospital, school or pub. Of course this depends upon the type of study population you are looking for and where it is likely to be found. Usually the purpose of the study is explained to potential respondents as they approach and their participation in the study is requested. apart from being slightly more time consuming, this method has all the advantages of administering a questionnaire collectively.

3.2. Choosing between an interview and a questionnaire

The choice between a questionnaire and an interview schedule is important and should be considered thoroughly as the strengths and weaknesses of the two methods can affect the validity of the findings. The nature of the investigation and the socioeconomic- demographic characteristics of the study population are central in this choice. The selection between an interview schedule and a questionnaire should be based upon the following criteria:

- The nature of the investigation – if the study is about issues that respondents may feel reluctant to discuss with an investigator, a questionnaire may be the better choice as it ensures anonymity. This may be the case with studies on drug use, sexuality, indulgence in criminal activities and personal finances. However, there are situations where better information about sensitive issues can be obtained by interviewing respondents. it depends on the type of study population and the skills of the interviewer.

- The geographical distribution of the study population – if potential respondents are scattered over a wide geographical area, you have no choice but to use a questionnaire, as interviewing in these circumstances would be extremely expensive.

- The type of study population – if the study population is illiterate, very young or very old, or handicapped, there may be no option but to interview respondents.

3.3. Advantages of a questionnaire

A questionnaire has several advantages:

- It is less expensive. As you do not interview respondents, you save time, and human and financial resources. The use of a questionnaire, therefore, is comparatively convenient and inexpensive. Particularly when it is administered collectively to a study population, it is an extremely inexpensive method of data collection.

- It offers greater anonymity. As there is no face-to-face interaction between respondents and interviewer, this method provides greater anonymity. in some situations where sensitive questions are asked it helps to increase the likelihood of obtaining accurate information.

3.4. Disadvantages of a questionnaire

Although a questionnaire has several disadvantages, it is important to note that not all data collection using this method has these disadvantages. The prevalence of a disadvantage depends on a number of factors, but you need to be aware of them to understand their possible bearing on the quality of the data. These are:

- Application is limited. One main disadvantage is that application is limited to a study population that can read and write. it cannot be used on a population that is illiterate, very young, very old or handicapped.

- Response rate is low. Questionnaires are notorious for their low response rates; that is, people fail to return them. if you plan to use a questionnaire, keep in mind that because not everyone will return their questionnaire, your sample size will in effect be reduced. The response rate depends upon a number of factors: the interest of the sample in the topic of the study; the layout and length of the questionnaire; the quality of the letter explaining the purpose and relevance of the study; and the methodology used to deliver the questionnaire. You should consider yourself lucky to obtain a 50 per cent response rate and sometimes it may be as low as 20 per cent. however, as mentioned, the response rate is not a problem when a questionnaire is administered in a collective situation.

- There is a self-selecting bias. not everyone who receives a questionnaire returns it, so there is a self-selecting bias. Those who return their questionnaire may have attitudes, attributes or motivations that are different from those who do not. hence, if the response rate is very low, the findings may not be representative of the total study population.

- Opportunity to clarify issues is lacking. if, for any reason, respondents do not understand some questions, there is almost no opportunity for them to have the meaning clarified unless they get in touch with you – the researcher (which does not happen often). If different respondents interpret questions differently, this will affect the quality of the information provided.

- Spontaneous responses are not allowed for. Mailed questionnaires are inappropriate when spontaneous responses are required, as a questionnaire gives respondents time to reflect before answering.

- The response to a question may be influenced by the response to other questions. As respondents can read all the questions before answering (which usually happens), the way they answer a particular question may be affected by their knowledge of other questions.

- It is possible to consult others. With mailed questionnaires respondents may consult other people before responding. In situations where an investigator wants to find out only the study population’s opinions, this method may be inappropriate, though requesting respondents to express their own opinion may help.

- A response cannot be supplemented with other information. An interview can sometimes be supplemented with information from other methods of data collection such as observation. however, a questionnaire lacks this advantage.

3.5. Advantages of the interview

- The interview is more appropriate for complex situations. it is the most appropriate approach for studying complex and sensitive areas as the interviewer has the opportunity to prepare a respondent before asking sensitive questions and to explain complex ones to respondents in person.

- It is useful for collecting in-depth information. In an interview situation it is possible for an investigator to obtain in-depth information by probing, hence, in situations where in-depth information is required, interviewing is the preferred method of data collection.

- Information can be supplemented. An interviewer is able to supplement information obtained from responses with those gained from observation of non-verbal reactions.

- Questions can be explained. It is less likely that a question will be misunderstood as the interviewer can either repeat a question or put it in a form that is understood by the respondent.

- Interviewing has a wider application. An interview can be used with almost any type of population: children, the handicapped, illiterate or very old.

3.6. Disadvantages of the interview

- Interviewing is time consuming and expensive. This is especially so when potential respondents are scattered over a wide geographical area. However, if you have a situation such as an office, a hospital or an agency where potential respondents come to obtain a service, interviewing them in that setting may be less expensive and less time consuming.

- The quality of data depends upon the quality of the interaction. In an interview the quality of interaction between an interviewer and interviewee is likely to affect the quality of the information obtained. Also, because the interaction in each interview is unique, the quality of the responses obtained from different interviews may vary significantly.

- The quality of data depends upon the quality of the interviewer. In an interview situation the quality of the data generated is affected by the experience, skills and commitment of the interviewer.

- The quality of data may vary when many interviewers are used. Use of multiple interviewers may magnify the problems identified in the two previous points.

- The researcher may introduce his/her bias. Researcher bias in the framing of questions and the interpretation of responses is always possible. If the interviews are conducted by a person or persons, paid or voluntary, other than the researcher, it is also possible that they may exhibit bias in the way they interpret responses, select response categories or choose words to summarise respondents’ expressed opinions.

3.7. Contents of the covering letter

It is essential that you write a covering letter with your mailed questionnaire. It should very briefly:

- introduce you and the institution you are representing;

- describe in two or three sentences the main objectives of the study;

- explain the relevance of the study;

- convey any general instructions;

- indicate that participation in the study is voluntary – if recipients do not want to respond to the questionnaire, they have the right not to;

- assure respondents of the anonymity of the information provided by them;

- provide a contact number in case they have any questions;

- give a return address for the questionnaire and a deadline for its return;

- thank them for their participation in the study.

3.8. Forms of question

The form and wording of questions used in an interview or a questionnaire are extremely important in a research instrument as they have an effect on the type and quality of information obtained from a respondent. The wording and structure of questions should therefore be appropriate, relevant and free from any of the problems discussed in the section titled ‘Formulating effective questions’ later in this chapter. Before this, let us discuss the two forms of questions, open ended and closed, which are both commonly used in social sciences research.

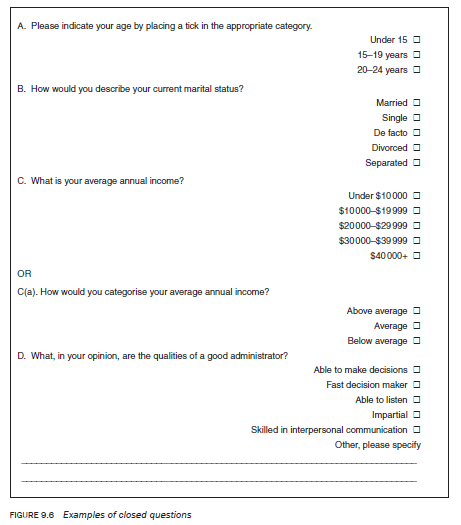

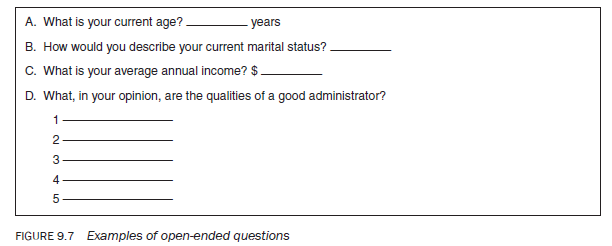

In an open-ended question the possible responses are not given. In the case of a questionnaire, the respondent writes down the answers in his/her words, but in the case of an interview schedule the investigator records the answers either verbatim or in a summary. In a closed question the possible answers are set out in the questionnaire or schedule and the respondent or the investigator ticks the category that best describes the respondent’s answer. It is usually wise to provide a category ‘Other/please explain’ to accommodate any response not listed. The questions in Figure 9.6 are classified as closed questions. The same questions could be asked as open-ended questions, as shown in Figure 9.7.

When deciding whether to use open-ended or closed questions to obtain information about a variable, visualise how you plan to use the information generated. This is important because the way you frame your questions determines the unit of measurement which could be used to classify the responses. The unit of measurement in turn dictates what statistical procedures can be applied to the data and the way the information can be analysed and displayed.

Let us take, as an example, the question about the variable: ‘income’. In closed questions income can be qualitatively recorded in categories such as ‘above average/average/below average’, or quantitatively in categories such as ‘under $10 000/$10 000—$19 999/…’. Your choice of qualitative and quantitative categories affects the unit of measurement for income (qualitative uses the ordinal scale and quantitative the ratio scale of measurement), which in turn will affect the application of statistical procedures. For example, you cannot calculate the average income of a person from the responses to question C(a) in Figure 9.6; nor can you calculate the median or modal category of income. But from the responses to question C, you can accurately calculate modal category of income. However, the average and the median income cannot be accurately calculated (such calculations are usually made under certain assumptions). From the responses to question C in Figure 9.7, where the income for a respondent is recorded in exact dollars, the different descriptors of income can be calculated very accurately. In addition, information on income can be displayed in any form. You can calculate the average, median or mode. The same is true for any other information obtained in response to open-ended and closed questions.

In closed questions, having developed categories, you cannot change them; hence, you should be very certain about your categories when developing them. If you ask an open-ended question, you can develop any number of categories at the time of analysis.

Both open-ended and closed questions have their advantages and disadvantages in different situations. To some extent, their advantages and disadvantages depend upon whether they are being used in an interview or in a questionnaire and on whether they are being used to seek information about facts or opinions. As a rule, closed questions are extremely useful for eliciting factual information and open-ended questions for seeking opinions, attitudes and perceptions. The choice of open-ended or closed questions should be made according to the purpose for which a piece of information is to be used, the type of study population from which information is going to be obtained, the proposed format for communicating the findings and the socioeconomic background of the readership.

3.9. Advantages and disadvantages of open-ended questions

- Open-ended questions provide in-depth information if used in an interview by an experienced interviewer. In a questionnaire, open-ended questions can provide a wealth of information provided respondents feel comfortable about expressing their opinions and are fluent in the language used. On the other hand, analysis of open-ended questions is more difficult. The researcher usually needs to go through another process – content analysis – in order to classify the data.

- In a questionnaire, open-ended questions provide respondents with the opportunity to express themselves freely, resulting in a greater variety of information. Thus respondents are not ‘conditioned’ by having to select answers from a list. The disadvantage of free choice is that, in a questionnaire, some respondents may not be able to express themselves, and so information can be lost.

- As open-ended questions allow respondents to express themselves freely, they virtually eliminate the possibility of investigator bias (investigator bias is introduced through the response pattern presented to respondents). On the other hand, there is a greater chance of interviewer bias in open-ended questions.

3.10. Advantages and disadvantages of closed questions

- One of the main disadvantages of closed questions is that the information obtained through them lacks depth and variety.

- There is a greater possibility of investigator bias because the researcher may list only the response patterns that s/he is interested in or those that come to mind. Even if the category of ‘other’ is offered, most people will usually select from the given responses, and so the findings may still reflect researcher bias.

- in a questionnaire, the given response pattern for a question could condition the thinking of respondents, and so the answers provided may not truly reflect respondents’ opinions. Rather, they may reflect the extent of agreement or disagreement with the researcher’s opinion or analysis of a situation.

- The ease of answering a ready-made list of responses may create a tendency among some respondents and interviewers to tick a category or categories without thinking through the issue.

- Closed questions, because they provide ‘ready-made’ categories within which respondents reply to the questions asked by the researcher, help to ensure that the information needed by the researcher is obtained and the responses are also easier to analyse.

3.11. Formulating effective questions

The wording and tone of your questions are important because the information and its quality largely depend upon these factors. It is therefore important to be careful about the way you formulate questions. The following are some considerations to keep in mind when formulating questions:

- Always use simple and everyday language. your respondents may not be highly educated, and even if they are they still may not know some of the ‘simple’ technical jargon that you are used to. Particularly in a questionnaire, take extra care to use words that your respondents will understand as you will have no opportunity to explain questions to them. A pre-test should show you what is and what is not understood by your respondents. For example:

is anyone in your family a dipsomaniac? (Bailey 1978: 100)

In this question many respondents, even some who are well educated, will not understand ‘dipsomaniac’ and, hence, they either do not answer or answer the question without understanding.

- Do not use ambiguous questions. an ambiguous question is one that contains more than one meaning and that can be interpreted differently by different respondents. This will result in different answers, making it difficult, if not impossible, to draw any valid conclusions from the information. The following questions highlight the problem:

Is your work made difficult because you are expecting a baby? (Moser & Kalton 1989: 323) yes □ No □

In the survey all women were asked this question. Those women who were not pregnant ticked ‘No’, meaning no they were not pregnant, and those who were pregnant and who ticked ‘No’ meant pregnancy had not made their work difficult. The question has other ambiguities as well: it does not specify the type of work and the stage of pregnancy.

Are you satisfied with your canteen? (Moser & Kalton 1989: 319)

This question is also ambiguous as it does not ask respondents to indicate the aspects of the canteen with which they may be satisfied or dissatisfied. Is it with the service, the prices, the physical facilities, the attitude of the staff or the quality of the meals? Respondents may have any one of these aspects in mind when they answer the question. Or the question should have been worded differently like, ‘are you, on the whole, satisfied with your canteen?’

- Do not ask double-barrelled questions. a double-barrelled question is a question within a question. The main problem with this type of question is that one does not know which particular question a respondent has answered. Some respondents may answer both parts of the question and others may answer only one of them.

How often and how much time do you spend on each visit?

This question was asked in a survey in Western Australia to ascertain the need for child-minding services in one of the hospitals. The question has two parts: how often do you visit and how much time is spent on each visit? in this type of question some respondents may answer the first part, whereas others may answer the second part and some may answer both parts. Incidentally, this question is also ambiguous in that it does not specify ‘how often’ in terms of a period of time. is it in a week, a fortnight, a month or a year?

Does your department have a special recruitment policy for racial minorities and women?

(Bailey 1978: 97)

This question is double barrelled in that it asks respondents to indicate whether their office has a special recruitment policy for two population groups: racial minorities and women. A ‘yes’ response does not necessarily mean that the office has a special recruitment policy for both groups.

- Do not ask leading questions. A leading question is one which, by its contents, structure or wording, leads a respondent to answer in a certain direction. Such questions are judgemental and lead respondents to answer either positively or negatively.

Unemployment is increasing, isn’t it?

Smoking is bad, isn’t it?

The first problem is that these are not questions but statements. Because the statements suggest that ‘unemployment is increasing’ and ‘smoking is bad’, respondents may feel that to disagree with them is to be in the wrong, especially if they feel that the researcher is an authority and that if s/he is saying that ‘unemployment is increasing’ or ‘smoking is bad’, it must be so. The feeling that there is a ‘right’ answer can ‘force’ people to respond in a way that is contrary to their true position.

- Do not ask questions that are based on presumptions. in such questions the researcher assumes that respondents fit into a particular category and seeks information based upon that assumption.

How many cigarettes do you smoke in a day? (Moser & Kalton 1989: 325)

What contraceptives do you use?

Both these questions were asked without ascertaining whether or not respondents were smokers or sexually active. In situations like this it is important to ascertain first whether or not a respondent fits into the category about which you are enquiring.

4. Constructing a research instrument in quantitative research

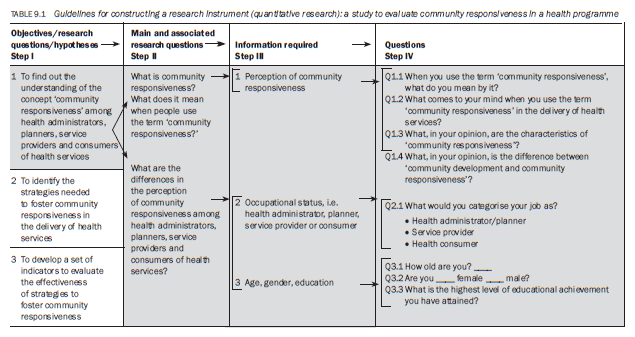

The construction of a research instrument or tool is an extremely important aspect of a research project because anything you say by way of findings or conclusions is based upon the type of information you collect, and the data you collect is entirely dependent upon the questions that you ask of your respondents. The famous saying about computers — ‘garbage in, garbage out’ — is also applicable to data collection. The research tool provides the input to a study and therefore the quality and validity of the output, the findings, are solely dependent upon it.

In spite of its immense importance, to the author’s knowledge, no specific guidelines for beginners on how to construct a research tool exist. Students are left to learn for themselves under the guidance of their research supervisor. The guidelines suggested below outline a broad approach, especially for beginners. The underlying principle is to ensure the validity of your instrument by making sure that your questions relate to the objectives of your study. Therefore, clearly defined objectives play an extremely important role as each question in the instrument must stem from the objectives, research questions and/or hypotheses of the study. It is suggested that a beginner should adopt the following procedure:

Step I If you have not already done so, clearly define and individually list all the specific objectives, research questions or hypotheses, if any, to be tested.

Step II For each objective, research question or hypothesis, list all the associated questions that you want to answer through your study.

Step III Take each question that you identified in Step II and list the information required to answer it.

Step IV Formulate question(s) that you want to ask of your respondents to obtain the required information.

In the above process you may find that the same piece of information is required for a number of questions. In such a situation the question should be asked once only. To understand this process, see Table 9.1 for which we have already developed a set of objectives in Figure 4.4 in Chapter 4.

5. Asking personal and sensitive questions

In the social sciences, sometimes one needs to ask questions that are of a personal nature. Some respondents may find this offensive. It is important to be aware of this as it may affect the quality of information or even result in an interview being terminated or questionnaires not being returned. Researchers have used a number of approaches to deal with this problem but it is difficult to say which approach is best. According to Bradburn and Sudman:

no data collection method is superior to other methods for all types of threatening questions. If one accepts the results at face value, each of the data gathering methods is best under certain conditions. (1979: 12—13)

In terms of the best technique for asking sensitive or threatening questions, there appears to be two opposite opinions, based on the manner in which the question is asked:

- a direct manner;

- an indirect manner.

The advantage with the first approach is that one can be sure that an affirmative answer is accurate. Those who advocate the second approach believe that direct questioning is likely to offend respondents and hence they are unlikely to answer even the non-sensitive questions. Some ways of asking personal questions in an indirect manner are as follows:

- by showing drawings or cartoons;

- by asking a respondent to complete a sentence;

- by asking a respondent to sort cards containing statements;

- by using random devices.

To describe these methods in detail is beyond the scope of this book.

6. The order of questions

The order of questions in a questionnaire or in an interview schedule is important as it affects the quality of information, and the interest and even willingness of a respondent to participate in a study. Again, there are two categories of opinion as to the best way to order questions. The first is that questions should be asked in a random order and the second is that they should follow a logical progression based upon the objectives of the study. The author believes that the latter procedure is better as it gradually leads respondents into the themes of the study, starting with simple themes and progressing to complex ones. This approach sustains the interest of respondents and gradually stimulates them to answer the questions. However, the random approach is useful in situations where a researcher wants respondents to express their agreement or disagreement with different aspects of an issue. In this case a logical listing of statements or questions may ‘condition’ a respondent to the opinions expressed by the researcher through the statements.

7. Pre-testing a research instrument

Having constructed your research instrument, whether an interview schedule or a questionnaire, it is important that you test it out before using it for actual data collection. Pre-testing a research instrument entails a critical examination of the understanding of each question and its meaning as understood by a respondent. A pre-test should be carried out under actual field conditions on a group of people similar to your study population. The purpose is not to collect data but to identify problems that the potential respondents might have in either understanding or interpreting a question. Your aim is to identify if there are problems in understanding the way a question has been worded, the appropriateness of the meaning it communicates, whether different respondents interpret a question differently, and to establish whether their interpretation is different to what you were trying to convey. If there are problems you need to re-examine the wording to make it clearer and unambiguous.

8. Prerequisites for data collection

Before you start obtaining information from potential respondents it is imperative that you make sure of their:

- motivation to share the required information – It is essential for respondents to be willing to share information with you. You should make every effort to motivate them by explaining clearly and in simple terms the objectives and relevance of the study, either at the time of the interview or in the covering letter accompanying the questionnaire and/or through interactive statements in the questionnaire.

- clear understanding of the questions – Respondents must understand what is expected of them in the questions. if respondents do not understand a question clearly, the response given may be either wrong or irrelevant, or make no sense.

- possession of the required information – The third prerequisite is that respondents must have the information sought. This is of particular importance when you are seeking factual or technical information. If respondents do not have the required information, they cannot provide it.

Source: Kumar Ranjit (2012), Research methodology: a step-by-step guide for beginners, SAGE Publications Ltd; Third edition.

29 Jul 2021

29 Jul 2021

30 Jul 2021

30 Jul 2021

29 Jul 2021

30 Jul 2021