No matter how well channels are designed and managed, there will be some conflict, if only because the interests of independent business entities do not always coincide. Channel conflict is generated when one channel member’s actions prevent another channel member from achieving its goal. Software giant Oracle Corp., plagued by conflict between its high-powered sales force and its vendor partners, has tried a number ofsolutions, including rolling out new

“All Partner Territories” where all deals except for specific strategic accounts go through select Oracle partners and allowing partners to secure bigger $1 billion-plus accounts.97

Channel coordination occurs when channel members are brought together to advance the goals of the channel instead of their own potentially incompatible goals.98 Here we examine three questions: What types of conflict arise in channels? What causes conflict? What can marketers do to resolve it?

1. TYPES OF CONFLICT AND COMPETITION

Suppose a manufacturer sets up a vertical channel consisting of wholesalers and retailers hoping for channel cooperation and greater profits for each member. Yet horizontal, vertical, and multichannel conflict can occur.

- Horizontal channel conflict occurs between channel members at the same level. Some Pizza Inn franchisees complained about others cheating on ingredients, providing poor service, and hurting the overall brand image.

- Vertical channel conflict occurs between different levels of the channel. When Estee Lauder set up a Web site to sell its Clinique and Bobbi Brown brands, the department store Dayton Hudson reduced the space it gave the company’s products.99 Greater retailer consolidation—the 10 largest U.S. retailers account for more than 80 percent of the average manufacturer’s business—has led to increased price pressure and influence from retailers.100 Walmart, for example, is the principal buyer for many manufacturers, including Disney, Procter & Gamble, and Revlon, and is able to command reduced prices or quantity discounts from these and other suppliers.101

- Multichannel conflict exists when the manufacturer has established two or more channels that sell to the same market.102 It’s likely to be especially intense when the members of one channel get a lower price (based on larger-volume purchases) or work with a lower margin. When Goodyear began selling its popular tire brands through Sears, Walmart, and Discount Tire, it angered its independent dealers and eventually placated them by offering exclusive tire models not sold in other retail outlets.

2. CAUSES OF CHANNEL CONFLICT

Some causes of channel conflict are easy to resolve; others are not. Conflict may arise from:

- Goal incompatibility. The manufacturer may want to achieve rapid market penetration through a low-price policy. Dealers, in contrast, may prefer to work with high margins and pursue short-run profitability.

- Unclear roles and rights. HP may sell laptops to large accounts through its own sales force, but its licensed dealers may also be trying to sell to large accounts. Territory boundaries and credit for sales often produce conflict.

- Differences in perception. The manufacturer may be optimistic about the short-term economic outlook and want dealers to carry higher inventory, while the dealers may be pessimistic. In the beverage category, it is not uncommon for disputes to arise between manufacturers and their distributors about the optimal advertising strategy.

- Intermediaries’ dependence on the manufacturer. The fortunes of exclusive dealers, such as auto dealers, are profoundly affected by the manufacturer’s product and pricing decisions. This situation creates a high potential for conflict.

3. MANAGING CHANNEL CONFLICT

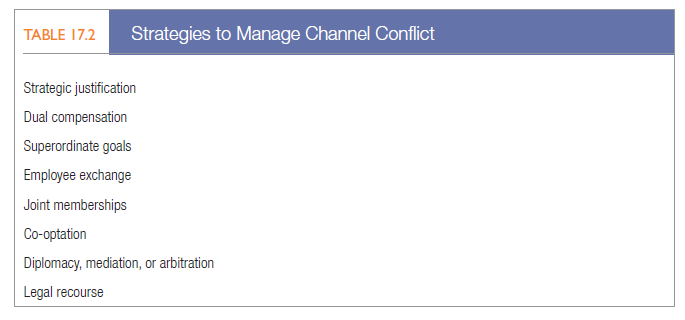

Some channel conflict can be constructive and lead to better adaptation to a changing environment, but too much is dysfunctional.103 The challenge is not to eliminate all conflict, which is impossible, but to manage it better. Verbal reprimands, fines, withheld bonuses, and other remedies can punish a firm in violation and deter others.104 Table 17.2 lists some mechanisms for effective conflict management that we discuss next.105

Strategic Justification In some cases, a convincing strategic justification that they serve distinctive segments and do not compete as much as they might think can reduce potential for conflict among channel members. Developing special versions of products for different channel members—branded variants as described in Chapter 11—is a clear way to demonstrate that distinctiveness.106

Dual Compensation Dual compensation pays existing channels for sales made through new channels. When Allstate started selling insurance online, it agreed to pay agents a 2 percent commission for face-to-face service to customers who got their quotes online. Although lower than the agents’ typical 10 percent commission for offline transactions, it did reduce tensions.107

Superordinate Goals Channel members can come to an agreement on the fundamental or superordinate goal they are jointly seeking, whether it is survival, market share, high quality, or customer satisfaction. They usually do this best when the channel faces an outside threat, such as a more efficient competing channel, an adverse piece of legislation, or a shift in consumer desires.

Employee Exchange A useful step is to exchange persons between two or more channel levels. GM’s executives might agree to work for a short time in some dealerships, and some dealership owners might work in GM’s dealer policy department. Thus participants can grow to appreciate each other’s point of view.

Joint Memberships Similarly, marketers can encourage joint memberships in trade associations. Good cooperation between the Grocery Manufacturers of America and the Food Marketing Institute, which represents most of the food chains, led to the development of the universal product code (UPC). The associations can consider issues between food manufacturers and retailers and resolve them in an orderly way.

Co-optation Co-optation is an effort by one organization to win the support of the leaders of another by including them in advisory councils, boards of directors, and the like. If the organization treats invited leaders seriously and listens to their opinions, co-optation can reduce conflict, but the initiator may need to compromise its policies and plans to win outsiders’ support.

Diplomacy, Mediation, and Arbitration When conflict is chronic or acute, the parties may need to resort to stronger means. Diplomacy takes place when each side sends a person or group to meet with its counterpart to resolve the conflict. Mediation relies on a neutral third party skilled in conciliating the two parties’ interests. In arbitration, two parties agree to present their arguments to one or more arbitrators and accept their decision.

Sometimes channel conflicts have to be settled by legal recourse as with Coca-Cola and its dispute with Walmart over Powerade.

Legal Recourse If nothing else proves effective, a channel partner may choose to file a lawsuit.108 When Coca- Cola decided to distribute Powerade thirst quencher directly to Walmart’s regional warehouses, 60 bottlers complained the practice would undermine their core direct-store-distribution (DSD) duties and filed suit. A settlement allowed for the mutual exploration of new service and distribution systems to supplement the DSD system.109

4. DILUTION AND CANNIBALIZATION

Marketers must be careful not to dilute their brands through inappropriate channels, particularly luxury brands whose images often rest on exclusivity and personalized service. Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger both took a hit when they sold too many of their products in discount channels.

Given the lengths to which they go to pamper customers in their stores—with doormen, glasses of champagne, and extravagant surroundings—luxury brands have had to work hard to provide a high-quality digital experience. They aren’t forgetting their stores, though, and are increasingly blending the two. Gucci partnered with Samsung Electronics to create an immersive in-store experience for its timepieces and jewelry that combines physical and mobile commerce. Stores feature transparent displays that show images on the screen without obscuring the products behind them and a digital shop-in-shop section where customers can use tablet computers to browse.110 To reach affluent customers who work long hours and have little time to shop, many high-end fashion brands such as Dior, Louis Vuitton, and Fendi have unveiled e-commerce sites for researching items before visiting a store—and a means to combat fakes sold online.

5. LEGAL AND ETHICAL ISSUES IN CHANNEL RELATIONS

Companies are generally free to develop whatever channel arrangements suit them. The law seeks to prevent only exclusionary tactics that might keep competitors from using a channel. Here we briefly consider the legality of certain practices, including exclusive dealing, exclusive territories, tying agreements, and dealers’ rights.

We saw earlier that in exclusive distribution, only certain outlets are allowed to carry a seller’s products, and that requiring these dealers not to handle competitors’ products is called exclusive dealing. Both channel partners benefit from exclusive arrangements: The seller obtains more loyal and dependable outlets, and the dealer gets a steady supply of special products and stronger seller support. Exclusive arrangements are legal as long as they do not substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly and as long as both parties enter into them voluntarily.

Exclusive dealing often includes exclusive territorial agreements. The producer may agree not to sell to other dealers in a given area, or the buyer may agree to sell only in its own territory. The first practice increases dealer enthusiasm and commitment. It is also perfectly legal—a seller has no legal obligation to sell through more outlets than it wishes. The second practice, whereby the producer tries to keep a dealer from selling outside its territory, has become a major legal issue.

Producers of a strong brand sometimes sell it to dealers only if they will take some or all of the rest of the line. This practice is called full-line forcing. Such tying agreements are not necessarily illegal, but they do violate U.S. law if they tend to lessen competition substantially.

Producers are free to select their dealers, but their right to terminate them is somewhat restricted. In general, sellers can drop dealers “for cause,” but not if, for example, a dealer refuses to cooperate in a doubtful legal arrangement, such as exclusive dealing or tying agreements.

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

You have brought up a very great points, thankyou for the post.

Just wanna remark on few general things, The website pattern is perfect, the subject material is very wonderful : D.