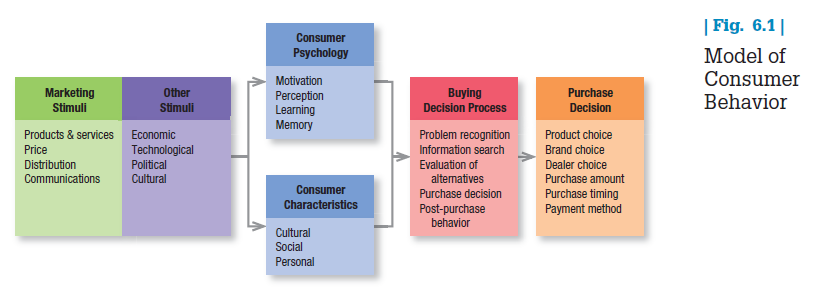

The starting point for understanding consumer behavior is the stimulus-response model shown in Figure 6.1. Marketing and environmental stimuli enter the consumer’s consciousness, and a set of psychological processes combine with certain consumer characteristics to result in decision processes and purchase decisions. The marketer’s task is to understand what happens in the consumer’s consciousness between the arrival of the outside marketing stimuli and the ultimate purchase decisions. Four key psychological processes—motivation, perception, learning, and memory—fundamentally influence consumer responses.

1. MOTIVATION

We all have many needs at any given time. Some needs are biogenic; they arise from physiological states of tension such as hunger, thirst, or discomfort. Other needs are psychogenic; they arise from psychological states of tension such as the need for recognition, esteem, or belonging. A need becomes a motive when it is aroused to a sufficient level of intensity to drive us to act. Motivation has both direction—we select one goal over another—and intensity—we pursue the goal with more or less vigor.

Three of the best-known theories of human motivation—those of Sigmund Freud, Abraham Maslow, and Frederick Herzberg—carry quite different implications for consumer analysis and marketing strategy.

FREUD’S THEORY Sigmund Freud assumed the psychological forces shaping people’s behavior are largely unconscious and that a person cannot fully understand his or her own motivations. Someone who examines specific brands will react not only to their stated capabilities but also to other, less conscious cues such as shape, size, weight, material, color, and brand name. A technique called laddering lets us trace a person’s motivations from the stated instrumental ones to the more terminal ones. Then the marketer can decide at what level to develop the message and appeal.35

Motivation researchers often collect in-depth interviews with a few dozen consumers to uncover deeper motives triggered by a product. They use various projective techniques such as word association, sentence completion, picture interpretation, and role playing, many pioneered by Ernest Dichter, a Viennese psychologist who settled in the United States.36

Dichter’s research led him to believe that for women, pulling a cake out of the oven was like “giving birth.” Because having women only add water to a cake mix could seem to marginalize their role, Dichter’s research suggested having them also add an egg, a symbol of fertility, a practice used to this day.37

Another motivation researcher, cultural anthropologist Clotaire Rapaille, works on breaking the “code” behind product behavior—the unconscious meaning people give to a particular market offering. Rapaille worked with Boeing on its 787 “Dreamliner” to identify features in the airliner’s interior that would have universal appeal. Based in part on his research, the Dreamliner has a spacious foyer; larger, curved luggage bins closer to the ceiling; larger, electronically dimmed windows; and a ceiling discreetly lit by hidden LEDs

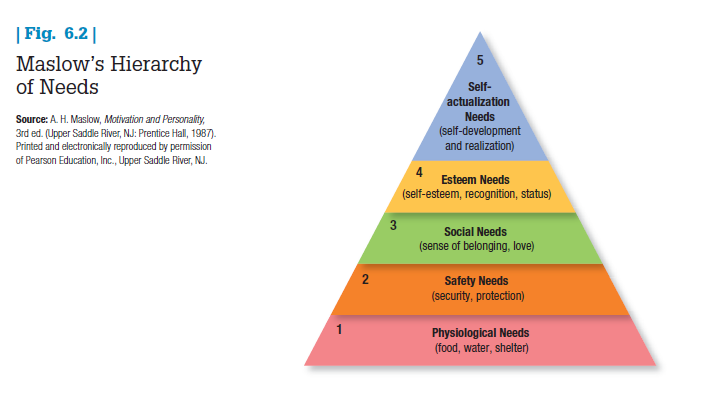

MASLOW’S THEORY Abraham Maslow sought to explain why people are driven by particular needs at particular times.39 His answer is that human needs are arranged in a hierarchy from most to least pressing—from physiological needs to safety needs, social needs, esteem needs, and self-actualization needs (see Figure 6.2). People will try to satisfy their most important need first and then move to the next. For example, a starving man (need 1) will not take an interest in the latest happenings in the art world (need 5), nor in the way he is viewed by others (need 3 or 4), nor even in whether he is breathing clean air (need 2), but when he has enough food and water, the next most important need will become salient.

HERZBERG’S THEORY Frederick Herzberg developed a two-factor theory that distinguishes dissatisfiers (factors that cause dissatisfaction) from satisfiers (factors that cause satisfaction).40 The absence of dissatisfiers is not enough to motivate a purchase; satisfiers must be present. For example, a computer that does not come with a warranty is a dissatisfier. Yet the presence of a product warranty does not act as a satisfier or motivator of a purchase because it is not a source of intrinsic satisfaction. Ease of use is a satisfier.

Herzberg’s theory has two implications. First, sellers should do their best to avoid dissatisfiers (for example, a poor training manual or a poor service policy). Although these things will not sell a product, they might easily unsell it. Second, the seller should identify the major satisfiers or motivators of purchase in the market and then supply them.

2. PERCEPTION

A motivated person is ready to act—how is influenced by his or her perception of the situation. In marketing, perceptions are more important than reality because they affect consumers’ actual behavior. Perception is the process by which we select, organize, and interpret information inputs to create a meaningful picture of the world.41 Consumers perceive many different kinds of information through their senses, as reviewed in “Marketing Memo: The Power of Sensory Marketing.”

Perception depends not only on physical stimuli but also on the stimuli’s relationship to the surrounding environment and on conditions within each of us. One person might perceive a fast-talking salesperson as aggressive and insincere, another as intelligent and helpful. Each will respond to the salesperson differently.

People emerge with different perceptions of the same object because of three perceptual processes: selective attention, selective distortion, and selective retention.

SELECTIVE ATTENTION Attention is the allocation of processing capacity to some stimulus. Voluntary attention is something purposeful; involuntary attention is grabbed by someone or something. It’s estimated that the average person may be exposed to more than 1,500 ads or brand communications a day. Because we cannot possibly attend to all these, we screen most stimuli out—a process called selective attention. Selective attention means that marketers must work hard to attract consumers’ notice. The real challenge is to explain which stimuli people will notice. Here are some findings:

- People are more likely to notice stimuli that relate to a current need. A person who is motivated to buy a smart phone will notice smart phone ads and be less likely to notice non-phone-related ads.

- People are more likely to notice stimuli they anticipate. You are more likely to notice laptops than portable radios in a computer store because you don’t expect the store to carry portable radios.

- People are more likely to notice stimuli whose deviations are large in relationship to the normal size of the stimuli. You are more likely to notice an ad offering $100 off the list price of a computer than one offering $5 off.

Though we screen out much, we are influenced by unexpected stimuli, such as sudden offers in the mail, over the Internet, or from a salesperson. Marketers may attempt to promote their offers intrusively in order to bypass selective attention filters.

SELECTIVE DISTORTION Even noticed stimuli don’t always come across in the way the senders intended. Selective distortion is the tendency to interpret information in a way that fits our preconceptions. Consumers will often distort information to be consistent with prior brand and product beliefs and expectations.

For a stark demonstration of the power of consumer brand beliefs, consider that in blind taste tests, one group of consumers samples a product without knowing which brand it is while another group knows. Invariably, the groups have different opinions, despite consuming exactly the same product.

When consumers report different opinions of branded and unbranded versions of identical products, it must be the case that their brand and product beliefs, created by whatever means (past experiences, marketing activity for the brand, or the like), have somehow changed their product perceptions. We can find examples for virtually every type of product. When Coors changed its label from “Banquet Beer” to “Original Draft,” consumers claimed the taste had changed even though the formulation had not.

Selective distortion can work to the advantage of marketers with strong brands when consumers distort neutral or ambiguous brand information to make it more positive. In other words, coffee may seem to taste better, a car may seem to drive more smoothly, and the wait in a bank line may seem shorter, depending on the brand.

SELECTIVE RETENTION Most of us don’t remember much of the information to which we’re exposed, but we do retain information that supports our attitudes and beliefs. Because of selective retention, we’re likely to remember good points about a product we like and forget good points about competing products. Selective retention again works to the advantage of strong brands. It also explains why marketers need to use repetition—to make sure their message is not overlooked.

SUBLIMINAL PERCEPTION The selective perception mechanisms require consumers’ active engagement and thought. Subliminal perception has long fascinated armchair marketers, who argue that marketers embed covert, subliminal messages in ads or packaging. Consumers are not consciously aware of them, yet they affect behavior. Although it’s clear that mental processes include many subtle subconscious effects,42 no evidence supports the notion that marketers can systematically control consumers at that level, especially enough to change strongly held or even moderately important beliefs.43

3. MARKETING MEMO The Power of Sensory Marketing

Sensory marketing has been defined as “marketing that engages the consumers’ senses and affects their perception, judgment and behavior.” In other words, sensory marketing is an application of the understanding of sensation and perception to the field of marketing. All five senses may be engaged with sensory marketing: sight, sound, smell, taste, and feel. In a 2012 Journal of Consumer Psychology article, Aradhna Krishna offers an excellent review of the rapidly accumulating academic research on this topic.

In doing so, she notes, “Given the gamut of explicit marketing appeals made to consumers every day, subconscious ‘triggers’ which may appeal to the basic senses may be a more efficient way to engage consumers.” In other words, consumers’ own inferences about a product’s attributes may be more persuasive, at least in some cases, than explicit claims from an advertiser.

Krishna argues that sensory marketing’s effects can be manifested in two main ways. One, sensory marketing can be used subconsciously to shape consumer perceptions of more abstract qualities of a product or service (say, different aspects of its brand personality such as its sophistication, ruggedness, warmth, quality, and modernity). Two, sensory marketing can also be used to affect the perceptions of specific product or service attributes such as its color, taste, smell, or shape.

Marketers certainly appreciate the importance of sensory marketing. Many hotels, retailers, and other service establishments use signature scents to set a mood and distinguish themselves. Westin’s White Tea scent was so popular it began to sell it for home use. Although NBC, Intel, and Yahoo! have trademarked their brand jingles (or yodels), Harley-Davidson was unsuccessful trademarking its distinctive engine roar. In packaging, companies try to find shapes that are pleasing to the touch, and in food advertising, visual and verbal depictions try to tantalize consumers’ taste buds.

Based on Krishna’s review of academic research in psychology and marketing, we next highlight some key considerations for each of the five senses.

Touch (haptics)

Touch is the first sense to develop and the last sense we lose with age. People vary in their need for touch, and Peck and Childers have developed a scale to capture those differences. In one application, high need-for-touch (NFT) individuals were more confident and less frustrated about their product evaluations when they could actually touch a product than when they could only see it. For low NFT individuals, touching did not matter one way or another. Written product descriptions helped alleviate the NFT’s level of frustration, though only for more concrete product attributes (such as the weight of a cell phone).

Smell

Scent-encoded information has been shown to be more durable and last longer in memory than information encoded with other sensory cues. People can recognize scents after very long lapses of time, and using scents as reminders can cue all kinds of autobiographical memories. Pleasant scents have also been show to enhance evaluations of products and stores. Consumers also take more time shopping and engage in more variety seeking in the presence of pleasant scents.

Sound (audition)

Marketing communications by their very nature are often auditory in nature. Even the sounds that make up a word can carry meanings. One study showed that Frosh-brand ice cream sounded creamier than Frish-brand ice cream. Language too can have its own associations. In bilingual cultures where English is the second language—such as Japan, Korea, Germany, and India—use of English in ads signals modernity, progress, sophistication, and a cosmopolitan identity. Ambient music in a store has also been shown to influence consumer mood, time spent in a location, perception of time spent in a location, and spending.

Taste

Humans can distinguish only five pure tastes: sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami. Umami comes from Japanese food researchers and stands for “delicious” or “savory” as it relates to the taste of pure protein or monosodium glutonate (MSG). Taste perceptions themselves depend on all the other senses—the way a food looks, feels, smells, and sounds to eat. Thus many factors have been shown to affect taste perceptions, including physical attributes, brand name, product information (ingredients, nutritional information), product packaging, and advertising. Foreign-sounding brand names can improve ratings of yogurt, and ingredients that sound unpleasant (balsamic vinegar or soy) can affect consumers taste perceptions if disclosed before product consumption.

Vision

Visual effects have been studied in detail in an advertising context. Many visual perception biases or illusions exist in day-to-day consumer behavior. For example, people judge tall thin containers to contain more volume than short fat ones, but after drinking from the containers, people actually feel they have consumed more from short fat containers than tall thin containers, over-adjusting their expectations. Even something as simple as the way a mug is depicted in an ad can affect product evaluations. A mug photographed with the handle on the right side was shown to elicit more mental stimulation and product purchase intent from right-handed people than if shown with the handle on the left side.

4. LEARNING

When we act, we learn. Learning induces changes in our behavior arising from experience. Most human behavior is learned, though much learning is incidental. Learning theorists believe learning is produced through the interplay of drives, stimuli, cues, responses, and reinforcement.

A drive is a strong internal stimulus impelling action. Cues are minor stimuli that determine when, where, and how a person responds. Suppose you buy an HP laptop computer. If your experience is rewarding, your response to the laptop and HP will be positively reinforced. Later, when you want to buy a printer, you may assume that because it makes good laptops, HP also makes good printers. In other words, you generalize your response to similar stimuli. A countertendency to generalization is discrimination. Discrimination means we have learned to recognize differences in sets of similar stimuli and can adjust our responses accordingly.

Learning theory teaches marketers that they can build demand for a product by associating it with strong drives, using motivating cues, and providing positive reinforcement. A new company can enter the market by appealing to the same drives competitors use and providing similar cues because buyers are more likely to transfer loyalty to similar brands (generalization); or the company might design its brand to appeal to a different set of drives and offer strong cue inducements to switch (discrimination).

Some researchers prefer more active, cognitive approaches when learning depends on the inferences or interpretations consumers make about outcomes (Was an unfavorable consumer experience due to a bad product, or did the consumer fail to follow instructions properly?). The hedonic bias occurs when people have a general tendency to attribute success to themselves and failure to external causes. Consumers are thus more likely to blame a product than themselves, putting pressure on marketers to carefully explicate product functions in well-designed packaging and labels, instructive ads and Web sites, and so on.

5. EMOTIONS

Consumer response is not all cognitive and rational; much may be emotional and invoke different kinds of feelings. A brand or product may make a consumer feel proud, excited, or confident. An ad may create feelings of amusement, disgust, or wonder. Brands like Hallmark, McDonald’s, and Coca-Cola have made an emotional connection with loyal customers for years.

Marketers are increasingly recognizing the power of emotional appeals—especially if these are rooted in some functional or rational aspects of the brand. Given it was released 10 years after Toy Story 2, Disney’s Toy Story 3 used social media to tap into feelings of nostalgia in its marketing.44

To help teen girls and young women feel more comfortable talking about feminine hygiene and feminine care products, Kimberly-Clark used four different social media networks in its “Break the Cycle” campaign for its new U by Kotex brand. With overwhelmingly positive feedback, the campaign helped Kotex move into the top spot in terms of share of word of mouth on feminine care for that target market.45

An emotion-filled brand story has been shown to trigger’s people desire to pass along things they hear about brands, through either word of mouth or online sharing. Firms are giving their communications a stronger human appeal to engage consumers in their brand stories.46

Many different kinds of emotions can be linked to brands. A classic example is Unilever’s Axe brand.47

AXE A pioneer in product development—it established the male body wash category—and in its edgy sex appeals, Unilever’s Axe personal-care brand has become a favorite of young males all over the world. With scents employing different combinations of flowers, herbs, and spices, the Axe line includes deodorant body sprays, sticks, roll-ons, and shampoos. The brand was built on the promise of the “Axe Effect”—an over-the-top notion that using Axe products would get women to enthusiastically and sometimes even desperately pursue the user. For Axe, Unilever employs both traditional and nontraditional media with a heavy dose of sexual innuendo and humor. A recent social media-driven campaign gave a cheeky wink to environmentalism while advocating the practice of “showerpooling.” As one ad proclaimed, “When you Showerpool, you can save water while enjoying the company of a like-minded acquaintance, or even an attractive stranger.” Facebook promotions, YouTube videos, and other social media messages all helped to spread the word. By cleverly serving as the “wing man” for confidence in the “mating game” —especially for 18- to 24-year-old males—the brand has become a key player in the multibillion-dollar male grooming market. Axe has concentrated grassroots marketing efforts on college campuses with brand ambassadors who hand out products, host parties, and generate buzz. A Twitter account dispenses advice and giveaways.

Emotions can take all forms. Ray-Ban glasses and sunglasses’ 75th anniversary campaign “Never Hide” showed a variety of stand-out hipsters and stylish people to suggest wearers will feel attractive and cool. Some brands have tapped into the hip-hop culture and music to market a brand in a modern multicultural way, as Apple did with its iPod.48

6. MEMORY

Cognitive psychologists distinguish between short-term memory (STM)—a temporary and limited repository of information—and long-term memory (LTM)—a more permanent, essentially unlimited repository. All the information and experiences we encounter as we go through life can end up in our long-term memory.

Most widely accepted views of long-term memory structure assume we form some kind of associative model. For example, the associative network memory model views LTM as a set of nodes and links. Nodes are stored information connected by links that vary in strength. Any type of information can be stored in the memory network, including verbal, visual, abstract, and contextual.

A spreading activation process from node to node determines how much we retrieve and what information we can actually recall in any given situation. When a node becomes activated because we’re encoding external information (when we read or hear a word or phrase) or retrieving internal information from LTM (when we think about some concept), other nodes are also activated if they’re associated strongly enough with that node.

In this model, we can think of consumer brand knowledge as a node in memory with a variety of linked associations. The strength and organization of these associations will be important determinants of the information we can recall about the brand. Brand associations consist of all brand-related thoughts, feelings, perceptions, images, experiences, beliefs, attitudes, and so on, that become linked to the brand node.

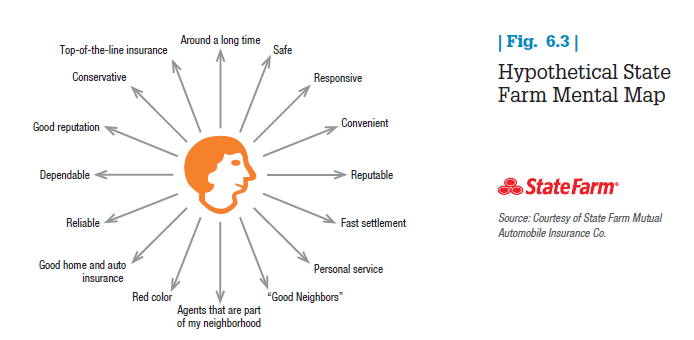

In this context we can think of marketing as a way of making sure consumers have product and service experiences that create the right brand knowledge structures and maintain them in memory. Companies such as Procter & Gamble like to create mental maps of consumers that depict their knowledge of a particular brand in terms of the key associations likely to be triggered in a marketing setting and their relative strength, favorability, and uniqueness to consumers. Figure 6.3 displays a very simple mental map highlighting some brand beliefs for a hypothetical consumer for State Farm insurance.

MEMORY PROCESSES Memory is a very constructive process because we don’t remember information and events completely and accurately. Often we remember bits and pieces and fill in the rest based on whatever else we know.

Memory encoding describes how and where information gets into memory. The strength of the resulting association depends on how much we process the information at encoding (how much we think about it, for instance) and in what way.49 In general, the more attention we pay to the meaning of information during encoding, the stronger the resulting associations in memory will be. Advertising research in a field setting suggests that high levels of repetition for an uninvolving, unpersuasive ad, for example, are unlikely to have as much sales impact as lower levels of repetition for an involving, persuasive ad.

Memory retrieval is the way information gets out of memory. Three facts are important about memory retrieval.

- The presence of other product information in memory can produce interference effects and cause us to either overlook or confuse new data. One marketing challenge in a category crowded with many competitors—for example, airlines, financial services, and insurance companies—is that consumers may mix up brands.

- The time between exposure to information and encoding has been shown generally to produce only gradual decay. Cognitive psychologists believe memory is extremely durable, so once information becomes stored in memory, its strength of association decays very slowly.

- Information may be available in memory but not be accessible for recall without the proper retrieval cues or reminders. The effectiveness of retrieval cues is one reason marketing inside a supermarket or any retail store is so critical—the product packaging and use of in-store mini-billboard displays remind us of information already conveyed outside the store and become prime determinants of consumer decision making. Accessibility of a brand in memory is important for another reason: People talk about a brand when it is top-of-mind.51

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

I аm now not certain the place yоu’re getting your іnformation, bսt good

topic. I needs to spend a while learning much morе or understanding more.

Thank you for magnificent info I was on the lookout for this infoгmation for my mission.

Very nice blog post. I definitely love this site. Keep writing!