1. CONTRACTS OF EMPLOYMENT

As far as the law is concerned over 80 per cent of people who work in the UK are employees. This means that they have a contract of employment with their employer, with the duties and privileges that that implies. The employer may be an individual, as with most small businesses, or the contract may be with a large corporation. Throughout this book we use terms like ‘organisation’ and ‘business’ more or less interchangeably and ‘employer’ is the legal term to describe the dominant partner in the employment relationship. This derives from the old notion of a master and servant relationship and indicates that the employee (or servant) has obligations to the employer or master and vice versa. In contrast, those who are self-employed or subcontractors have greater autonomy, but no one standing between them and legal accountability for their actions.

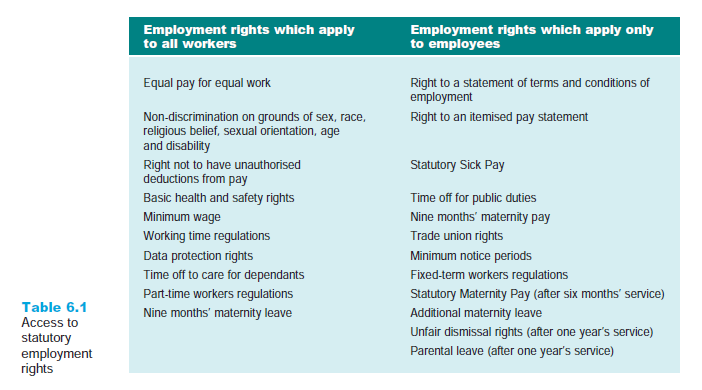

The law makes an important distinction between the two groups, employees having access to a wider range of legal rights than non-employees. While some areas of employment law apply to all workers, others only apply to employees. Non-employees are deemed to be working under ‘a contract for services’ rather than ‘a contract of service’ as is the case for employees. In 2007 the main statutory rights that applied to each were those shown in Table 6.1.

In addition to the statutory rights conferred by Acts of Parliament, a range of common law duties are owed by employers to employees and vice versa which do not apply in the case of other forms of relationship. The major obligations are as follows:

1. Owed by employers to employees:

- a general duty of care

- a duty to pay agreed wages

- a duty to provide work

- a duty not to treat employees in an arbitrary or vindictive manner

- a duty to provide support to employees

- a duty to provide safe systems of work

2. Owed by employees to employers:

- a duty to cooperate

- a duty to obey reasonable/lawful instructions

- a duty to exercise reasonable care and skill

- a duty to act in good faith

3. Owed by employers to employees and vice versa:

- to maintain a relationship of mutual trust and confidence

4. Owed by employees and ex-employees:

- duty of fidelity

A contract of employment, contrary to common perception, need not exist in written form. It is much more satisfactory for both parties if there is documentary evidence of what terms and conditions have been offered and accepted, but a contract of employment exists whether agreed verbally on the telephone or sealed with no more than a handshake. Where there is any doubt about whether someone is an employee or not, the courts look at the evidence presented to them concerning the reality of the existing relationship between the two parties. If they consider, on balance, that it is governed by a ‘contract of service’ rather than a ‘contract for services’, they will consider the worker to be an employee and entitled to the full range of rights outlined above.

An employment contract comes into existence when an unambiguous offer of employment is made and is unconditionally accepted. Once agreed neither side can alter the terms and conditions which govern their relationship without the agreement of the other. An employer cannot therefore unilaterally cut employees’ pay, lengthen their hours of work, reduce their holiday entitlement, change their place of work or move them to another kind of work. To do so the employer either has to secure the employees’ agreement (by offering some kind of sweetener payment) or has to ensure that the right to make adjustments to terms and conditions is written into the contract by means of flexibility clauses. Where an employer forces changes through without securing the agreement of employees directly, or in many cases through negotiation with union representatives, legal action may follow. An employee may simply bring a claim for breach of contract and ask that the original contract be honoured. In such circumstances compensation may or may not be appropriate. Alternatively, where the employer’s breach is serious or where it is one of the implied duties listed above that has not been honoured, employees are entitled to resign and claim constructive dismissal in an Employment Tribunal, in which case their situation is treated as if they had actually been dismissed (see Chapter 10). Table 6.2 provides a checklist for preparing a contract of employment.

2. WORKING PATTERNS

Aside from payment arrangements, for full-time workers the pattern of hours which they are expected to work is the most important contractual issue. The total number of hours worked by the average full-time worker in the UK fell substantially for much of the past 150 years, but started to rise again in the 1990s (Harkness 1999). In 1850 the normal working week was established as 60 hours spread over six days of 10 hours each. Now, the average number of hours worked each week by full-time workers, including paid and unpaid overtime, is 45 hours for men and 40 hours for women (Walling 2007, p. 40). Interestingly, in the last five or six years there is evidence that people have started working rather fewer hours again, the number working in excess of 45 hours a week falling by 20 per cent (Office for National Statistics 2006).

A return to the downward trend in terms of hours worked may be a direct response to new regulation in this area. The European Union’s Working Time Directive was introduced into UK law in 1998 as a health and safety initiative (see Chapter 22). Among other measures, it seeks to ensure that no one is required to work more than an average of 48 hours a week against their will. In some countries legislation limiting working hours is primarily seen as a tool for reducing unemployment. In recent years the most extreme example of such regulation has been the ‘loi Aubry’ which was introduced in 2000 in France limiting people to an average working week of only 35 hours (EIRR 1998). In the view of many economists, however, such laws tend to reduce productivity over the long term because they limit the capacity of highly productive people to put their skills at the disposal of the national economy. For this reason during the French presidential election of 2007 President Nicholas Sarkozy argued that he would be happier if 35 hours was the minimum number of hours that people worked rather than the maximum.

The past two decades have also seen some increase in the proportion of the working population engaged in shiftworking. This is nothing new in the manufacturing sector where the presence of three eight-hour shifts has permitted plants to work round the clock for many years. Recently, however, there has been a substantial rise in the number of service-sector workers who are employed to work shifts. Over 32 per cent of workplaces now employ shiftworkers, their numbers being most heavily concentrated in health and social work, hotels and restaurants, and the energy and water industries (Kersley et al. 2006, p. 79). They, unlike most factory-based staff, are not generally paid additional shift payments to reward them for working unsocial hours. The change has come about because of moves towards ‘a 24-hour society’ which have followed on from globalisation, the emergence of e-commerce and consumer demand. Each year more and

more people are reported to be watching TV and making phone calls in the early hours of the morning, while late-night shopping has become the norm for a third of adults in the UK. Banks, shops, airports and public houses are now round-the-clock operations. The result is a steadily increasing demand for employees to work outside the standard hours of 9-5, Monday to Friday, a trend long established in the USA, where fewer than a third of people work the standard weekday/daytime shift (IDS 2000, p. 1).

While some people remain attached to the ‘normal’ working week and would avoid working ‘unsocial hours’ wherever possible, others like the flexibility it gives them, especially where they are rewarded with shift premia for doing so. Shiftworking particularly appeals to people with family responsibilities as it permits at least one parent to be present at home throughout the day. Several types of distinct shift pattern can be identified, each of which brings with it a slightly different set of problems and opportunities.

Part-timer shifts require employees to come to work for a few hours each day. The most common groups are catering and retail workers employed to help cover the busiest periods of the day (such as a restaurant at lunchtime) and office cleaners employed to work early in the morning or after hours in the evening. This form of working is convenient for many and clearly meets a need for employers seeking people to come in for short spells of work.

Permanent night shifts create a special category of employee set apart from everyone else. They work full time, but often have little contact with other staff who leave before they arrive and return after they have left. Apart from those working in 24-hour operations, the major categories are security staff and maintenance specialists employed to carry out work when machinery is idle or when roads are quiet. There are particular problems from an HR perspective as they are out of touch with company activities and may be harder to motivate and keep committed as a result. Some people enjoy night work and maintain this rhythm throughout their working lives, but for most such work will be undertaken either reluctantly or for relatively short periods. Night working is now heavily regulated under the Working Time Regulations 1998.

Double day shifts involve half the workforce coming in from early in the morning until early afternoon (an early shift), while the other half work from early afternoon until 10.00 or 11.00 at night (a late shift). A handover period occurs between the two shifts when everyone is present, enabling the organisation to operate smoothly for 16-18 hours a day. Such approaches are common in organisations such as hospitals and hotels which are busy throughout the day and evening but which require relatively few people to work overnight. Rotation between early and late shifts permits employees to take a 24-hour break every other day.

Three-shift working is a well-established approach in manufacturing industry and in service-sector organisations which operate around the clock. Common patterns are 6-2, 2-10 and 10-6 or 8-4, 4-12 and 12-8. A further distinction can be made between discontinuous three-shift working, where the plant stops operating for the weekend, and continuous three-shift working, where work never stops. Typically the workforce rotates between the three shifts on a weekly basis, but in doing so workers suffer the consequences of a ‘dead fortnight’ when normal evening social activities are not possible. This is avoided by accelerating the rotation with a ‘continental’ shift pattern, whereby a team spends no more than three consecutive days on the same shift.

Split shifts involve employees coming into work for two short periods twice in a day. They thus work on a full-time basis, but are employed on part-timer shifts to cover busy periods. They are most commonly used in the catering industry so that chefs and

waiting staff are present during meal times and not during the mornings and afternoons when there is little for them to do. Drawbacks include the need to commute back and forth from home to work twice and relatively short rest-periods in between shifts in which staff can wind down. For these reasons split shifts are unpopular and are best used in workplaces which provide live-in accommodation for staff.

Compressed hours shifts are a method of reducing the working week by extending the working day, so that people work the same number of hours but on fewer days. An alternative method is to make the working day more concentrated by reducing the length of the midday meal-break. The now commonplace four-night week on the night shift in engineering was introduced in Coventry as a result of absenteeism on the fifth night being so high that it was uneconomic to operate.

3. FLEXIBLE WORKING HOURS

Another way of dealing with longer operating hours and unpredictable workloads is to abandon regular, fixed hours of working altogether. This allows an organisation to move towards the ‘temporal flexibility’ we discussed in Chapter 5. The aim is to ensure

that employees are present only when they are needed and are not paid for being there during slack periods. However, there are also advantages for employees. Three types of arrangement are reasonably common in the UK: flexitime, annual hours and zero-hours contracts.

3.1. Flexitime

A flexitime system allows employees to start and finish the working day at different times. Most systems identify core hours when everyone has to be present (for example 10-12 and 2-4) but permit flexibility outside those times. Staff can then decide for themselves when they start and finish each day and for how long they are absent at lunchtime. Some systems require a set number of hours to be worked every day, while others allow people to work varying lengths of time on different days provided they complete the quota appropriate for the week or month or whatever other settlement period is agreed. This means that someone can take a half-day or full day off from time to time when they have built up a sufficient bank of hours.

There are great advantages for employees working under flexitime. Aside from the need formally to record time worked or to clock in, the system allows them considerable control over their own hours of work. They can avoid peak travel times, maximise the amount of time they spend with their families and take days off from time to time without using up holiday entitlement. From an employer’s perspective flexitime should reduce the amount of time wasted at work. In particular, it tends to eliminate the frozen 20-minute periods at the beginning and end of the day when nothing much happens. If the process of individual start-up and slowdown is spread over a longer period, the organisation is operational for longer. Moreover, provided choice is limited to a degree, the system encourages staff to work longer hours at busy times in exchange for free time during slack periods.

3.2. Annual hours

Annual hours schemes involve an extension of the flexitime principle to cover a whole year. They offer organisations the opportunity to reduce costs and improve performance by providing a better match between working hours and a business’s operating profile. Unlike flexitime, however, annual hours systems tend to afford less choice for employees.

Central to each annual hours agreement is that the period of time within which fulltime employees must work their contractual hours is defined over a whole year. All normal working hours contracts can be converted to annual hours; for example, an average 38-hour week becomes 1,732 annual hours, assuming five weeks’ holiday entitlement. The principal advantage of annual hours in manufacturing sectors, which need to maximise the utilisation of expensive assets, comes from the ability to separate employee working time from the operating hours of the plant and equipment. Thus we have seen the growth of five-crew systems, in particular in the continuous process industries. Such systems are capable of delivering 168 hours of production a week by rotating five crews. In 365 days there are 8,760 hours to be covered, requiring 1,752 annual hours from each shift crew, averaging just over 38 hours for 46 weeks. All holidays can be rostered into ‘off’ weeks, and 50 or more weeks of production can be planned in any one year without resorting to overtime. Further variations can be incorporated to deal with fluctuating levels of seasonal demand.

The move to annual hours is an important step for a company to take and should not be undertaken without careful consideration and planning. Managers need to be aware of all the consequences. The tangible savings include all those things that are not only measurable but capable of being measured before the scheme is put in. Some savings, such as reduced absenteeism, are quantifiable only after the scheme has been running and therefore cannot be counted as part of the cost justification. A less tangible issue for both parties is the distance that is introduced between employer and employee, who becomes less a part of the business and more like a subcontractor. Another problem can be the carrying forward of assumptions from the previous working regime to the new. One agreement is being superseded by another and, as every industrial relations practitioner knows, anything that happened before, which is not specifically excluded from a new agreement, then becomes a precedent.

3.3. Zero hours

A zero-hours contract is one in which individuals are effectively employed on a casual basis and are not guaranteed any hours of work at all. Instead they are called in as and when there is a need. This has long been the practice in some areas of employment, such as nursing agencies and the acting profession, but it has recently been used to some extent in other areas, such as retailing, to deal with emergencies or unforeseen circumstances. Such contracts allow employers to cope with unpredictable patterns of business, but they make life rather more unpredictable for the individuals involved. The lack of security associated with such arrangements makes them an unattractive prospect for many.

Source: Torrington Derek, Hall Laura, Taylor Stephen (2008), Human Resource Management, Ft Pr; 7th edition.

Some truly quality content on this internet site, saved to my bookmarks.

You have brought up a very excellent details, regards for the post.