1. METHODS OF RECRUITMENT

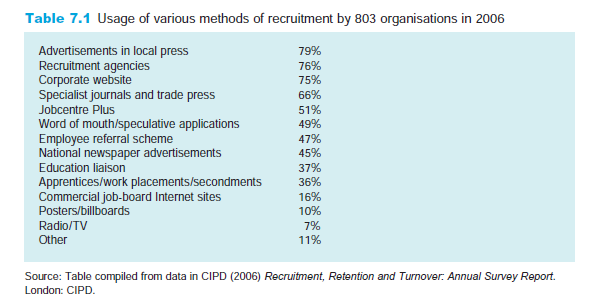

Once an employer has decided that external recruitment is necessary, a cost-effective and appropriate method of recruitment must be selected. There are a number of distinct approaches to choose from, each of which is more or less appropriate in different circumstances. As a result most employers use a wide variety of different recruitment methods at different times. In many situations there is also a good case for using different methods in combination when looking to fill the same vacancy. Table 7.1 sets out the usage of different methods reported in a recent CIPD survey of 802 UK employers (CIPD 2006).

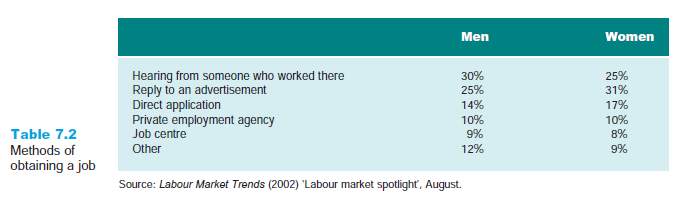

It is interesting to compare the figures in Table 7.1 with those reported in surveys of how people actually find their jobs in practice. These repeatedly show that informal methods (such as word of mouth and making unsolicited applications) are as common as, if not more common than, formal methods such as recruitment advertising. In 2002, the Labour Force Survey asked over a million people how they had obtained their current job. The results are shown in Table 7.2.

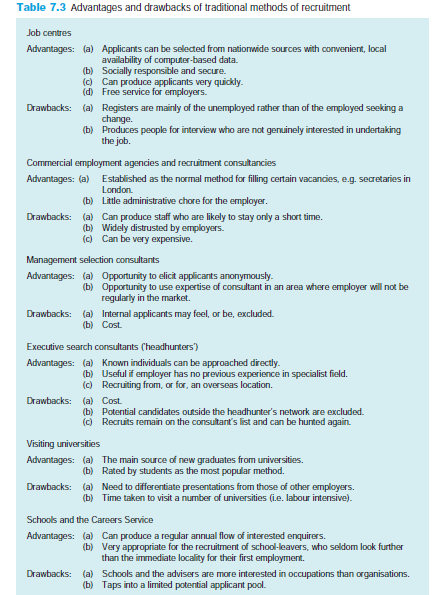

2. THE RECRUITMENT METHODS COMPARED

All the various methods of recruitment have benefits and drawbacks, and the choice of a method has to be made in relation to the particular vacancy and the type of labour market in which the job falls. A general review of advantages and drawbacks is given in Table 7.3.

3. RECRUITMENT ADVERTISING

In order to assist them in drafting advertisements and placing them in suitable media, many employers deal with a recruitment advertising agency. Such agencies provide expert advice on where to place advertisements and how they should be worded and will design them attractively to achieve maximum impact. Large organisations often subcontract all their advertising work to an agency with whom a mutually acceptable service-level agreement has been signed.

Recruitment advertising companies (as opposed to headhunters and recruitment consultants) are often inexpensive because the agency derives much of its income from the commission paid by the journals on the value of the advertising space sold, the bigger agencies being able to negotiate substantial discounts because of the amount of business they place with the newspapers and trade journals. A portion of this saving is then passed on to the employer so that it can easily be cheaper and a great deal more effective to work with an agent providing this kind of service. The HR manager placing, say, £50,000 of business annually with an agency will appreciate that the agency’s income from that will be between £5,000 and £7,500, and will expect a good standard of service. The important questions relate to the experience of the agency in dealing with recruitment,as compared with other types of advertising, the quality of the advice they can offer about media choice and the quality of response that their advertisements produce.

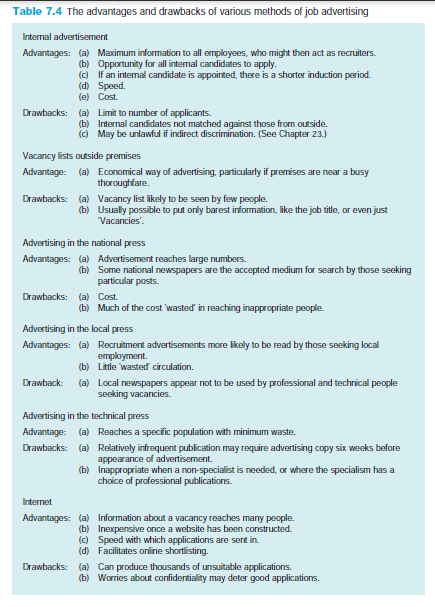

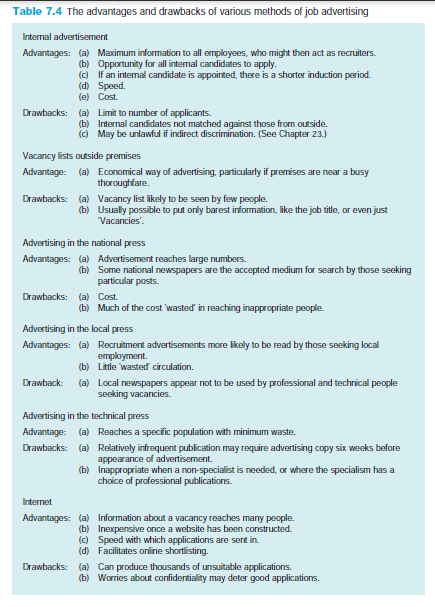

In choosing where to place a recruitment advertisement the aim is to attract as many people as possible with the required skills and qualifications and to reach people who are either actively looking for a new job or thinking about doing so. The need is therefore to place the advertisement where job seekers who are qualified to take on the role are most likely to look. Except in very tight labour markets, where large numbers of staff are required at the same time, there is no point in placing a recruitment advertisement outside a newspaper or journal’s recruitment pages. In some situations newspaper readership figures are helpful when deciding where to advertise. An example would be where there are two or more established trade journals or local newspapers competing with one another, both of which carry numerous recruitment advertisements. Otherwise readership figures are unimportant because people tend to buy different newspapers when job searching than they do the rest of the time. It is often more helpful to look at the share of different recruitment advertising markets achieved by the various publications, as this gives an indication of where particular types of job are mostly advertised. In the UK in recent years the Guardian newspaper has gained and sustained a 40 per cent market share of national recruitment advertising. For many jobs in the media, education and the public sector it is now established as the first port of call for job seekers. This has been achieved by cutting rates to less than half those charged by other national newspapers. For the more senior private sector jobs, however, the established market leaders are the Daily Telegraph, the Sunday Times and the Financial Times. While recruitment advertising agents are well placed to advise on these issues, it is straightforward to get hold of information about rates charged by different publications and their respective market shares. Good starting points are the websites of British Rate and Data (www.brad.co.uk), which carries up-to-date information about thousands of publications, and the National Readership Survey (www.nrs.co.uk) which provides details of readership levels among different population groups. Table 7.4 reviews the advantages and drawbacks of various methods of job advertising.

Drafting the advertisement

The decision on what to include in a recruitment advertisement is important because of the high cost of space and the need to attract attention; both factors will encourage the use of the fewest number of words. Where agencies are used they will be able to advise on this, as they will on the way the advertisement should be worded, but the following is a short checklist of items that must be included.

- Name and brief details of employing organisation

- Job role and duties

- Training to be provided

- Key points of the personnel specification or competency profile

- Salary

- Instructions about how to apply

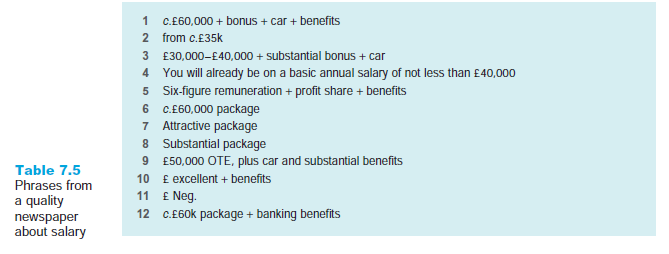

Many employers are coy about declaring the salary that will accompany the advertised post. Sometimes this is reasonable as the salary scales are well known and inflexible, as in much public sector employment. Elsewhere the coyness is due either to the fact that the employer has a general secrecy policy about salaries and does not want to publicise the salary of a position to be filled for fear of dissatisfying holders of other posts, or does not know what to offer and is waiting to see ‘what the mail brings’. All research evidence, however, suggests that a good indication of the salary is essential if the employer is to attract a useful number of appropriate replies (see Barber 1998, pp. 42-3).

4. E-RECRUITMENT

The use of the Internet for recruitment purposes is, along with the substantial recent growth in international recruitment, the most striking recent development in the field, but its practical significance remains a question of debate. When the Internet first became widely used ten or fifteen years ago it was often predicted that it would revolutionise the recruitment industry. In the future, it was argued, most of us would find out about jobs through web searches. It now appears that these predictions greatly overstated the influence that the Internet would have. Incomes Data Services came to the following conclusion having carried out an extensive survey of approaches used by UK organisations:

Although the significance of online recruitment is growing, it has to be remembered that the medium is not appropriate for all jobs or for all candidates. There are still some people who are not comfortable using a computer and even ‘web savvy’ applicants may be deterred by the perceived impersonal nature of online recruitment… There is, therefore, still a role for conventional advertising, particularly when recruiting locally or for hard-to- fill jobs. Ultimately, many employers may seek to combine online and traditional approaches to maximise their chances of securing the best candidate. (IDS 2006, p. 2)

Internet recruitment takes two basic forms. The first is centred on the employer’s own website, jobs being advertised alongside information about the products and services offered by the organisation. The second approach makes use of the growing number of cyber-agencies which combine the roles traditionally played by both newspapers and employment agents. They advertise the job and undertake shortlisting before they send on a selection of suitable CVs to the employer.

For employers the principal attraction is the way that the Internet allows jobs to be advertised inexpensively to a potential audience of millions. According to Frankland (2000) the cost of setting up a good website is roughly equivalent to that associated with advertising a single high-profile job in a national newspaper. Huge savings can also be made by dispensing with the need to print glossy recruitment brochures and other documents to send to potential candidates. The other big advantage is speed. People can respond within seconds of reading about an opportunity by emailing their CV to the employer. Shortlisting can also be undertaken quickly with the use of CV-matching software or online application forms.

In principle e-recruitment thus has a great deal to offer. In practice, however, there are major problems which may take many more years to iron out. A key drawback is the way that employers advertising jobs tend to get bombarded with hundreds of applications. This occurs because of the large number of people who read the advertisement and because it takes so little effort to email a copy of a pre-prepared CV to the employer concerned. In order to prevent ‘spamming’ of this kind it is necessary to make use of online shortlisting software which is able to screen out unsuitable applications. Such technologies, however, are not wholly satisfactory. Those which work by looking for key words in CVs inevitably have a ‘hit and miss’ character and can be criticised for being inherently unfair. The possibility that good candidates may not be considered simply because they have not chosen a particular word or phrase is strong. The same is true of online application systems which include a handful of ‘killer’ questions designed to sift out unsuitable candidates at a very early stage. The tendency is for people who have a somewhat unconventional career background simply to be disregarded when, in fact, they may have the required talent or potential to do an excellent job.

The alternative is to require candidates to apply online by completing a pschyometric test. This approach has the advantage of deterring candidates who are not prepared to invest the time and effort required to complete the forms, but is unreliable in important respects – there is no guarantee that the test is in fact being completed by the candidate, nor is it completed within a standard, pre-determined time limit. Other problems concern fears about security and confidentiality which serve to deter people from submitting personal details over the web:

Everybody should be familiar with the fear of using a credit card on-line even though good e-commerce sites have secure servers that enable these transactions to take place safely. The job-seeker’s equivalent of this is ‘how safe is it to put my CV on-line?’ Although the figures prove that plenty of people have overcome this fear (there are an estimated 4.5 million CVs on-line), horror stories of candidates’ CVs ending up on their employer’s desktop aren’t entirely without foundation. (Weekes 2000, p. 35)

Criticisms have also been made about poor standards of ethicality on the part of cyberagencies. As with conventional employment agents there are a number who employ sharp practices such as posting fictional vacancies and falsely inflating advertised pay rates in order to build up a bank of CVs which can be circulated to employers on an

unsolicited basis. Some cyber-agencies also copy CVs from competitors’ sites and send them on to employers without authorisation. Over time, as the industry grows, professional standards will be established and a regulatory regime established, but for the time being such problems remain.

The fact that there are so many drawbacks alongside the advantages explains why so many employers appear to use the Internet for recruitment while rating it relatively poorly. When asked to rank recruitment methods in terms of their effectiveness very few employers place the Internet at the top of the list (only 7 per cent according to a 2003 CIPD survey). While employers rank the Internet highly vis-a-vis other methods in terms of its cost effectiveness, they are much less convinced when asked about the quality of applicants and the ability of web-based advertising to source the right candidates (IRS 2005, p. 45). Established approaches such as newspaper advertising and education liaison are much more highly rated and are thus unlikely to be replaced by e-recruitment in the near future. However, over the longer term, technological developments and increased web usage may improve the effectiveness of e-recruitment considerably. In 2007 it was announced by Ofcom (the telecommunications regulatory body) that over half of adults in the UK have broadband Internet connections at home, while many more can access the web speedily at work, in a library, job centre, educational institution or Internet cafe. Ultimately it is likely that one or two very well-funded job sites will emerge from the current mass and will be in a position to command substantial shares of the market. We may then have a situation in which anyone seeking a new job in a particular field will make a familiar website rather than the newspaper or journal their first port of call.

5. RECRUITING OVERSEAS

As labour markets have tightened, skills shortages have become more acute and as employers have found it harder to recruit UK-based staff at a level of salary that is affordable, they have increasingly been looking overseas as a major source of staff. The accession of ten new countries to the EU in 2004 greatly assisted in this respect, permitting, according to official estimates, over half a million people to come into the UK to work by the end of 2006 (Blanchflower et al. 2007).

Citizens of EU countries that joined the Union prior to January 2007 are permitted to work in the UK without a permit; this includes countries such as Poland and Hungary which have become major sources of staff for UK employers in recent years. People from countries acceding in 2004, however, must in most cases register with the government under its Worker Registration Scheme and then apply for a residence permit after completing a years’ continuous service with a UK employer. Work permits are not required by people coming from countries in the European Economic Area (EEA) but not in the EU (such as Norway and Switzerland), citizens of British Overseas Territories (e.g. Gibraltar) or people from Commonwealth states whose parents or grandparents were born in the UK. Spouses of UK citizens who retain an overseas nationality can also work in the UK without a permit. For people who do not fall into one of these categories there are complex rules which will determine whether or not they can receive a work permit and for how long they are able to stay in the UK to work thereafter. Different rules apply, for example, to students studying in the UK, to spouses of people with work permits, and to people from overseas who have qualifications that are in short supply in the UK. At the time of writing (2007) a new streamlined system for granting work permits and rights of residence is being developed by the government and will soon be implemented. It will be points based, making it a great deal easier for someone in their early twenties with a higher degree, and a high existing salary, to obtain a permit than someone who is older, poorer and less highly educated. Low-skilled workers from outside the EU will effectively have no possibility of entering the UK legally to work, except on a temporary basis in very limited situations.

Running large-scale overseas recruitment campaigns is expensive and it is an activity that has to be planned carefully if it is to yield effective results. Over recent years, as demand for overseas workers has increased, a number of well-run agencies with a high level of knowledge and experience of specific labour markets have become established, and many employers have used them. Others, particularly NHS Trusts and larger recruiters of skilled workers, have developed their own competence in this area and recruit directly. IDS (2005) gives the following sound advice:

- Recruit in countries where skills and qualifications are comparable with those in the UK. This reduces the length of time it takes for each new migrant worker to adapt and begin performing at a high level.

- Recruit in countries with relatively high unemployment and relatively low wages vis-a-vis the UK. Elsewhere workers will have a great deal less motivation to move to the UK.

- Meet potential candidates face to face before employing them. Do not rely on telephone interviews or the opinion of an agency. This typically involves flying managers out to an overseas destination to run intensive interview days or assessment centres.

- Ensure that candidates have strong communication skills and a sufficient level of competence in the English language before recruiting them.

- Ensure that appropriate accommodation is provided when the new recruits first arrive in the UK along with support systems so that they feel welcome and become effective quickly.

It is also important to be aware of the various ethical issues associated with overseas recruitment. Care must be taken, for example, to ensure equal treatment with UK nationals so that neither group perceives that the other is being given favourable treatment by their employers. Another major ethical issue relates to the recruitment of ‘key workers’ such as doctors and nurses in developing countries where they are in short supply. In recent years a number of governments have rightly complained that the NHS is robbing local health providers of the staff they need to help ensure the health of their own people.

6. EMPLOYER BRANDING

In recent years considerable interest has developed in the idea that employers have much to gain when competing for staff by borrowing techniques long used in marketing goods and services to potential customers. In particular, many organisations have sought to position themselves as ‘employers of choice’ in their labour markets with a view to attracting stronger applications from potential employees. Those who have succeeded have often found that their recruitment costs fall as a result because they get so many more unsolicited applications (see Taylor 2002, p. 449).

Central to these approaches is the development over time of a positive ‘brand image’ of the organisation as an employer, so that potential employees come to regard working there as highly desirable. Developing a good brand image is an easier task for larger companies with household names than for those which are smaller or highly specialised, but the possibility of developing and sustaining a reputation as a good employer is something from which all organisations stand to benefit.

The key, as when branding consumer products, is to build on any aspect of the working experience that is distinct from that offered by other organisations competing in the same broad applicant pool. It may be relatively high pay or a generous benefits package, it may be flexible working, or a friendly and informal atmosphere, strong career development potential or job security. This is then developed as a ‘unique selling proposition’ and forms the basis of the employer branding exercise. The best way of finding out what is distinct and positive about working in your organisation is to carry out some form of staff attitude survey. Employer branding exercises simply amount to a waste of time and money when they are not rooted in the actual lived experience of employees because people are attracted to the organisation on false premises. As with claims made for products that do not live up to their billing, the employees gained are not subsequently retained, and resources are wasted recruiting people who resign quickly after starting.

Once the unique selling propositions have been identified they can be used to inform all forms of communication that the organisation engages in with potential and actual applicants. The aim must be to repeat the message again and again in advertisements, in recruitment literature, on Internet sites and at careers fairs. It is also important that existing employees are made aware of their employer’s brand proposition too as so much recruitment is carried out informally through word of mouth. Provided the message is accurate and provided it is communicated effectively over time, the result will be a ‘leveraging of the brand’ as more and more people in the labour market begin to associate the message with the employer.

Source: Torrington Derek, Hall Laura, Taylor Stephen (2008), Human Resource Management, Ft Pr; 7th edition.

This internet site is my breathing in, rattling excellent style and perfect content material.