1. ATYPICAL CONTRACTUAL ARRANGEMENTS

Recent decades have seen the growth of contractual arrangements that differ from the permanent, open-ended, full-time, workplace-based form of employment that has always been regarded as representing the norm. There has always been considerable disagreement about the significance of these trends. For some they mark the ‘beginning of the end’ for jobs as we have come to experience them over the past 100 years, while for others they represent a modest adjustment of traditional practices in response to evolving labour market developments and to industrial restructuring. Either way they have important implications for the effective management of people.

1.1. Contracts of limited duration

Contracts of employment vary in all manner of ways. One of the most important distinctions relates to their length. Here it is possible to identify three basic forms:

- Permanent: This is open ended and without a date of expiry.

- Fixed term: This has a fixed start and finish date, although it may have provision for notice before the agreed finish date.

- Temporary: Temporary contracts are for people employed explicitly for a limited period, but with the expiry date not precisely specified. A common situation is where a job ends when a defined source of funding comes to an end. Another is where someone is employed to carry out a specified task, so that the expiry date is when the task is complete. The employer is obliged to give temporary workers an indication in writing at the start of their employment of the expected duration of the job.

Around half of all employers in the UK, including a good majority of public sector bodies, employ some people on a fixed-term basis or make use of agency temps. In 2005 a total of 1.4 million people worked under some form of non-permanent contract, which is 5.6 per cent of all employees (Office of National Statistics 2006). This is appreciably more than the 5 per cent who were employed on such a basis in the 1980s, but represents a substantial fall over the past few years; in 1998 the figure was close to 1.8 million. As unemployment has fallen and the economy has grown employers have found that they have to offer permanent positions if they are to attract effective employees. Although only around a quarter of temporary staff now claim that they would prefer a permanent job, in the mid-1990s this figure was close to half.

Some of the reasons for employing people on a temporary or fixed-term basis are obvious. Retail stores need more staff immediately before Christmas than in February and ice cream manufacturers need more people in July than November, so both types of business have seasonal fluctuations. Nowadays, however, there is the additional factor of flexibility in the face of uncertainty. Will the new line sell? Will there be sustained business after we have completed this particular contract? In the public sector fixed-term employment has grown with the provision of funds to carry out one-off projects, while the signing of time-limited service provision agreements with external private-sector companies has also become a great deal more common.

Often temporary staff are needed to cover duties normally carried out by a permanent employee. This can be due to sickness absence or maternity leave, or it may occur when there is a gap between one person resigning and another taking up the post. Another common approach is to employ new starters on a probationary basis, confirming their appointments as permanent when the employer is satisfied that they will perform their jobs successfully.

Some argue (e.g. Geary 1992) that managers have a preference for temporary staff because the use of such people gives them a greater degree of control over labour. This control derives from the fact that many temporary staff would dearly love to secure greater job security in order to gain access to mortgages and to allow them to plan their future lives with greater certainty. As a result temporary workers are often keenest to impress and will work beyond their contract in a bid to gain permanent jobs. Their absence levels also tend to be low. Because they work under the constant, unspoken threat of dismissal, they feel the need to behave with total compliance to avoid this. Managers sometimes take advantage of such a situation and push people into working harder than is good for them.

The law on the employment of fixed-term workers has changed in recent years and this may well in part account for the reduction in their numbers. Until October 1999 it was possible to employ staff on fixed-term contracts which contained clauses waiving the right to claim unfair dismissal. This meant that the employer could terminate the relationship by failing to renew the contract whether or not there was a good reason for doing so. It was thus possible substantially to avoid liability for claims of unfair dismissal by employing people on a succession of short contracts. For fixed-term contracts entered into after October 1999 waiver clauses no longer apply. Henceforth employers who do not renew a fixed-term contract have had to be able to justify their decision just as they do with any other dismissal, if they want to avoid court action. Temporary and fixed-term workers also gained a number of further rights via the Employment Act 2002 which implemented the EU’s Fixed-term Work Directive. This seeks to ensure that temporary employees enjoy the same terms and conditions as permanent employees undertaking equivalent roles, that employers inform them of permanent vacancies and allow them access to training opportunities. The new law also seeks to limit the number of times that an employer can renew a fixed-term contract without making it permanent without good reason. Since 2006 people who have been employed on a temporary basis for four years or more are entitled to permanent contracts unless the employer can objectively justify less favourable treatment. They are also now entitled to redundancy payments when they are laid off.

A special type of contract is that for apprenticeship. Although this is not seen as a contract of employment for the purpose of accumulating employment rights, it is a form of legally binding working relationship that pre-dates all current legislative rights in employment, and the apprentice therefore has additional rights at common law relating to training. An employer cannot lawfully terminate an apprentice’s contract before the agreed period of training is complete, unless there is closure or a fundamental change of activity in the business to justify redundancy.

1.2. Part-time contracts

At one time part-time working was relatively unusual and was scarcely economic for the employer as the national insurance costs of the part-time employee were disproportionate to those of the full-timer. The part-time contract was regarded as an indulgence for the employee and only a second-best alternative to the employment of someone full time. This view was endorsed by lower rates of pay, little or no security of employment and exclusion from such benefits as sick pay, holiday pay and pension entitlement. The situation has now wholly changed.

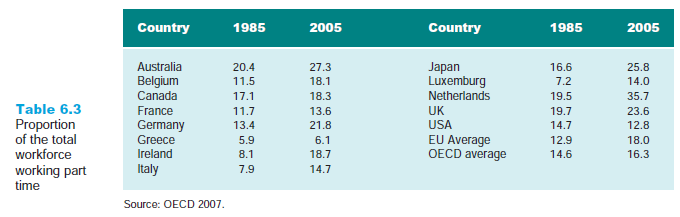

Since the 1960s the proportion of the employed workforce on part-time contracts has increased dramatically. Around a quarter of us (seven million) now work on a part-time basis, compared to just 9 per cent in 1961. Between 1992 and 2006 the number of fulltime jobs in the UK increased by 10 per cent, while the rate of increase in part-time jobs was 23 per cent. Here too, however, there has been a modest reduction in the most recent years, the figure peaking in 2004. Table 6.3 shows that this proportion is greater than that in most other countries, although there is some difficulty in making precise comparisons because the definition of what constitutes a part-time job varies somewhat from country to country. Whatever the definition used, however, it is clear that the number of part-timers across the world has steadily grown over recent decades. Only in the USA has the number declined of late.

Women account for four-fifths of all part-time workers in the UK, 44 per cent of all female workers being employed on a part-time basis and only 11 per cent of men. Male part-timers are overwhelmingly in the 16-19 and over 65 age groups, suggesting that full-time work is the preference for most men between leaving school and retiring. In the case of women the age pattern is markedly different. Around a quarter of women work on a part-time basis in their twenties, but this figure rises to 40 per cent for women aged 30-34 and to 50 per cent for those aged 35-39. After that the proportion declines somewhat until close to retirement. Among women, therefore, part-time work appears very frequently to be undertaken during the time that their children are at school and that it is the preference for many. Among women with dependent children who work part time, government statistics report that 94 per cent do not want a full-time job (Labour Market Trends 2003).

Many part-timers work short shifts and sometimes two will share a full working day. Others will be in positions for which only a few hours within the normal day are required or a few hours at particular times of the week. Retailing is an occupation that has considerable scope for the part-timer, as there is obviously a greater need for counter personnel on Saturday mornings than on Monday mornings. Also many shops are now open for longer periods than would be normal hours for a full-time employee, so that the part-timer helps to fill the gaps and provide the extra staffing at peak periods. Catering is another example, as is market research interviewing, office cleaning, clerical work and some posts in education.

Unjustified discrimination against part-time workers has effectively been outlawed in the UK since 1994 when it was held by the courts potentially to amount to indirect discrimination on grounds of sex. Since 2000, however, statute has required that all part- timers and full-timers are treated equally. The Part-time Workers (Prevention of Less Favourable Treatment) Regulations provide that part-time workers are to be given the same pay per hour and the same terms and conditions of employment as full-time colleagues undertaking the same or similar work. All benefits must also be provided to part-timers on a pro-rata basis. Moreover, the regulations state that employers cannot

subject workers to a detriment of any kind simply because they work part time. This means, for example, that both part-time and full-time workers must be given equal access to training. It also means that the fact that an employee works part time should not be taken into account when deciding who is to be made redundant. Unlike other forms of direct discrimination, however, in the case of part-timers employers can seek to justify their actions on objective grounds.

1.3. Distance working

In the quest for greater flexibility many employers are beginning to explore new ways of getting work done which do not involve individuals working full time on their premises. Working overseas, selling in the field and home-working are the most obvious types of distance working, but advances in information technology have led to increased interest in the concepts of teleworking and tele-cottaging. The term tele is the Greek for distant, which is familiar to us in words such as telegram and television.

The total number of UK workers who either are based at home or work mainly from home is just over 3 million (around 8 per cent of the total workforce). But a large proportion of these people are self-employed (Office for National Statistics 2006, p. 25). Despite the possibilities for such arrangements deriving from new technologies, only around 200,000 employees in the UK are based mainly at home, a further 380,000 being mobile workers who use their home as their base (IDS 2005, p. 2).

The main advantage, for both the employer and the employee, is the flexibility that teleworking can provide, but the employer also benefits from reduced office accommodation costs and potential increases in productivity. Employees avoid the increasingly time-consuming activity of commuting to work and can manage their own workload around their home responsibilities and leisure interests. But there is a downside too. Many find working from home all the time to be a rather isolating experience and miss the social life and sense of belonging to a community of colleagues that comes with traditional employment.

The main problem for employers, aside from fostering staff morale, commitment and a sense of corporate identity, is the need to maintain a reasonable degree of management control when the workforce is so geographically diffused. Drawing up an appropriate job specification is thus particularly important in the case of teleworking jobs. It is important to set out clearly defined parameters of action, criteria for decisions and issues which need reference back. Person specifications are also crucial since in much distance working there is less scope for employees to be trained or socialised on the job. In addition, ‘small business’ skills are likely to be needed by teleworkers, networkers, consultants and subcontractors.

Attention also needs to be given to the initial stages of settling in distance workers. Those off-site need to know the pattern of regular links and contacts to be followed. Those newly recruited to the company need the same induction information as regular employees. In fact, those working independently with less supervision may need additional material, particularly on health and safety. Heightened team-building skills will also be needed to encompass staff who are working on a variety of different contracts and at different locations.

The final key aspect of employing distance workers is the need for a close link between pay and performance. Managers must be able to specify job targets and requirements accurately and to clarify and agree these with the employees concerned. Where a fee rather than a salary is paid, the onus is on the manager to ensure the work has been completed satisfactorily.

1.4. Self-employment

In the UK 3.7 million people are self-employed, which is around 13 per cent of the total workforce. The proportion is somewhat higher in London and the south-east than elsewhere in the country because that is where the industries which employ most selfemployed people are most common. Weir (2003) shows that demand for the services of self-employed people is lowest in manufacturing and in the public services. By contrast there are many more opportunities for self-employment in the construction, retailing, property, business services and personal services industries. Three-quarters of selfemployed people work for themselves or in partnership with one other person and they are heavily concentrated in skilled trades and professional services occupations. They also tend to be a good deal older than average workers, as many as 31 per cent of older workers employing themselves.

The 1980s saw a substantial growth in the number of self-employed people. The growth slowed down in the 1990s, but started increasing again after 2002. There is some debate about the reasons for these patterns. Lindsay and Macaulay (2004) have examined the data in some detail. One possibility they consider is a response to changes in taxation which were made in the early years of the twenty-first century aimed at assisting small businesses. Another is a change in the way that the government gathers the statistics, but detailed examination of the trends suggests that neither of these is a plausible explanation. What seems to be happening is that people are in a better position than they were to set up their own businesses because of rises in house prices during this time. People are leaving employment and are using their houses as collateral to raise the necessary finance. The particular growth in self-employment that can be observed occurring in the finance industry appears to result from large redundancy payments made as finance houses have restructured in order to compete more effectively internationally.

What is clear is that most employed people earn considerably more than most selfemployed people (Weir 2003, p. 449). While around 17 per cent of self-employed people earn well in excess of the national average, the big majority earn substantially less. Some running fledgling businesses struggle to earn anything at all. Some of these earnings figures may be subject to some under-reporting for tax avoidance reasons, but they firmly dispel the myth that self-employment is a route to affluence and an easy life. Many more selfemployed people work longer hours for less reward than those employed by organisations.

Increasing the proportion of the workforce that is hired on a self-employed basis has both attractions and drawbacks for employers. While self-employed people typically

cost more per hour to employ, they only need to be paid for the time they actually spend completing a job or can simply be paid a set fee for the completion of a project irrespective of how long it takes. The fact that they can be asked to tender for work in competition with others tends to further reduce costs, as does the fact that a self-employed person manages their own taxation and pension arrangements. So overall there are often major savings to be made in replacing certain jobs in an organisation with self-employed people. Moreover, as was shown at the start of this chapter, huge swathes of employment rights such as unfair dismissal and paid maternity leave apply only to employees and not to those employed on a subcontracted basis. The negative implications derive from the inevitable fact that a self-employed person is not obliged to work exclusively for one employer or even to work uniquely in the interests of any one organisation. The relationship is thus more distant and conditional on external influences for its continuance. This can mean that only the minimum acceptable levels of quality are achieved in practice and that the contribution made by the worker to longer-term business development is severely limited. An employer can buy a self-employed person’s expertise, but cannot draw on the full range of their energies and commitment as is possible in the case of well-managed employees to whom a longer-term commitment has been made and with whom a closer personal relationship has been forged.

2. CONSULTANTS

Some management consultants are self-employed people who have gained considerable experience over some years and are in a position to sell their expertise to organisations for a fee. Many more are employed by larger firms which also provide a range of other business services. These tend to be younger people who have substantial, specialist, technical knowledge of particular areas of business activity. Consultants offer advice about issues faced by organisations, but they are also in a position to carry out research, to design new policies and procedures, and to brief or train staff in their effective use. Nowadays a lot of their work involves selling already developed IT products to clients and assisting them to put these into operation. In the HR field this is true of consultancies that specialise in job evaluation and in the provision of personnel information systems.

In many ways consultants thus provide a service analogous to that of an accountant, a lawyer or a financial adviser. However the service is packaged, organisations are being invited to buy their professional expertise and to apply it (or not) as they see fit. Substantial demand for such services over recent years has meant that consultancy has grown into a major multi-billion pound international industry employing hundreds of thousands of highly qualified people, many of whom are in a position to charge their clients upwards of £3,000 per day. Yet, despite their having been a fixture on the management scene for decades, there remains considerable cynicism about consultancy as a trade (see the poem overleaf entitled ‘The Business Consultant’). The following quotation from the leading industrialist Lord Weinstock is born of disappointing experiences:

Consultants are invariably a waste of money. There has been the occasional instance where a useful idea has come up, but the input we have received has usually been banal and unoriginal, wrapped up in impressive sounding but irrelevant rhetoric. (Caulkin 1997)

The use of consultants is thus a matter about which managers are very divided. In some companies, and increasingly in public-sector organisations, they are employed regularly and found to offer a useful if expensive service. Elsewhere it appears almost to be a matter of policy to resist their blandishments and to tap into alternative sources of advice. The best approach, as with all major purchasing decisions, is to employ them only in situations where there is a good business case for doing so and where they are likely to add value. The most likely scenario is where the organisation needs specialist advice and cannot gain access to it through its internal resources. In the HR field an example would be the need to develop a competitive employment package for an individual who is being sent on long-term expatriate assignment to a country with which people within the organisation are largely unfamiliar. It makes sense in such a situation to take advice from someone who has technical knowledge of the tax systems, pay rates and living standards in that country. Another common situation in which consultants are employed in the HR field is to administer psychometric selection tests to candidates applying for jobs and then to interpret and provide feedback on the results. However, there can also be other reasons for their employment, as Duncan Wood (1985) found in his interviews with well-established HR consultants:

- To provide specialist expertise and wider knowledge not available within the client organisation.

- To provide an independent view.

- To act as a catalyst.

- To provide extra resources to meet temporary requirements.

- To help develop a consensus when there are divided views about proposed changes.

- To demonstrate to employees the impartiality/objectivity of personnel changes or decisions.

- To justify potentially unpleasant decisions.

The likelihood of securing a positive outcome when employing consultants depends on two conditions being present. First, it is essential that the consultant is given very clear instructions both about the nature of the issue or problem that they are being asked to advise about, and about what the client expects of them. Second, they should only be employed once it has first been established that they are likely to be able to provide knowledge and ideas that cannot be sourced in-house, and that the costs associated with their employment are justified.

3. OUTSOURCING

Consultants are mainly employed to give advice or to carry out a defined project. In employing them an organisation is effectively subcontracting part of its management process. But organisations can and do subcontract out to specialist service providers a great deal more than in the past. The outsourcing of functions which either could be or were previously carried out in-house has become much more common in recent years. It is a trend that creates its own momentum because the more outsourcing that occurs, the bigger and better the providers become, making it an increasingly viable proposition for more organisations. According to the most recent Workplace Employment Relations Survey 86 per cent of organisations subcontract a service of some kind (Kersley et al.2006, p. 106).

Of particular interest to readers of this book is the strong trend that can now be discerned towards the outsourcing (either in whole or in part) of activities that have traditionally been carried out by the HR function in organisations. You will find further information and discussion exercises about this on our companion website www.pearsoned.co.uk/torrington.

According to Colling (2005) the organisational functions which are most commonly outsourced by UK organisations are ancillary services such as cleaning, catering, security, transportation and buildings maintenance. There is nothing new about organisations subcontracting such functions to external providers, but there is clearly an increased trend in that direction. Twenty years ago most larger corporations and the entire public sector managed these ancillary services themselves, employing their own people to carry them out. This is less and less true. Increasingly managers are keen to focus all their energies on their ‘core business activities’, by which they mean those activities which are the source of competitive advantage and which determine the success or failure of their organisations. There is thus a desire to minimise the amount of management time and effort which is spent carrying out more marginal activities. The decision to outsource is made easier by the fact that specialist security, cleaning and catering companies are often in a position to provide a higher-quality standard of service at a lower cost than can be achieved by in-house operations. This is because for them the provision of ancillary services is the core business and they have the expertise, up-to-date equipment, and staff to run highly efficient operations. Moreover, their size means that they can benefit from economies of scale that are not available to the far smaller locally run operations.

The nature and standard of services that the external company provides are determined by the service level agreement that is signed. This will usually follow on from a competitive tendering exercise in which providers of outsourced services compete with one another to secure a three- or five-year contract. If the standards of service fall short of those set out in the agreement, the purchasing organisation is then able to look elsewhere, and can in any case sign a new agreement with a different provider at the end of the contract. This should ensure that high standards are maintained, but the evidence suggests that outsourcing frequently disappoints in practice. Reilly (2001, p. 135) lists all manner of problems that occur due to poor communication, differences of opinion about the service levels being achieved and different interpretations of terms in the contract. These occur because it will always be in the interests of the providing company to keep its costs low and in the interests of the purchasing company to demand higher standards of service and value for money.

In practice the theoretical advantages of outsourcing thus often fail to materialise. Serious cost savings are often difficult to achieve, largely because the Transfer of Undertakings laws require existing staff to be retained by the new service provider on their existing terms and conditions, yet standards of service may actually decline. Loss of day- to-day control means that problems take longer to rectify because complaints have to be funnelled through to managers of the providing company and cannot simply be addressed on the spot. It is also hard in practice to replace one contractor with another, as well as being costly, because there are a limited number of companies that are both viable over the long term and interested in putting in a bid. So great care has to be taken when adopting this course of action. Expectations need to be managed and deals should only be signed with providers who can demonstrate a record of satisfactory service achieved in comparable organisations.

These potential obstacles have not stopped a number of large corporations from outsourcing large portions of their HR functions in recent years. The service level agreements that are signed typically involve a specialist provider taking over responsibility for the more routine administrative tasks that are traditionally carried out by in-house HR teams. These include payroll administration, the maintenance of personnel databases, the provision of intranet services which set out HR policies, recruitment administration and routine training activities. Such arrangements enable the organisation to dispense with the services of junior HR staff and to retain small teams of more senior people to deal with policy issues, sensitive or confidential matters and union negotiations.

Source: Torrington Derek, Hall Laura, Taylor Stephen (2008), Human Resource Management, Ft Pr; 7th edition.

Very good written post. It will be beneficial to anyone who utilizes it, including yours truly :). Keep up the good work – for sure i will check out more posts.