Whether they let their business units set their own goals and strategies or collaborate in doing so, all corporate headquarters undertake four planning activities:

- Defining the corporate mission

- Establishing strategic business units

- Assigning resources to each strategic business unit

- Assessing growth opportunities

We’ll briefly look at each process.

1. MARKETING MEMO What Does It Take to Be a Successful CMO?

The challenge chief marketing officers (CMOs) face is that success factors are many and varied. CMOs must have strong quantitative and qualitative skills; they must have an independent, entrepreneurial attitude but work closely with other departments; and they must capture the “voice” of consumers yet have a keen bottom-line understanding of how marketing creates value. Two-thirds of top CMOs think return-on-marketing-investment (ROMI) will be the primary measure of their effectiveness in 2015.

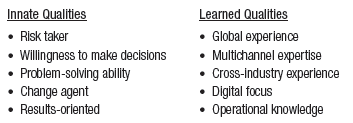

One survey asking 200 senior-level marketing executives which innate and learned qualities were most important yielded these answers:

Marketing experts George Day and Robert Malcolm believe three driving forces will change the role of the CMO in the coming years: (1) predictable marketplace trends, (2) the changing role of the C-suite, and (3) uncertainty about the economy and organizational design. They identify five priorities for any successful CMO:

- Act as the visionary for the future of the company.

- Build adaptive marketing capabilities.

- Win the war for marketing talent.

- Tighten the alignment with sales.

- Take accountability for returns on marketing spending.

Perhaps the most important role for any CMO is to infuse a customer perspective in business decisions affecting any customer touch point (where a customer directly or indirectly interacts with the company). Increasingly, these customer insights must have a global focus. As one top executive search firm leader said, “Tomorrow’s CMO will have to have global and international experience. You can do it without living abroad . . . but you have to get exposure to those markets. It opens your eyes to new ways of doing business, increases cultural sensitivity and increases flexibility.”

Sources: Jennifer Rooney, “CMO Tenure Hits 43-Month Mark,” Forbes, June 14, 2012; Steven Cook, “It’s Time to Raise the CMO Bar,” www.cmo.com, January 24, 2012; “From Stretched to Strengthened: Insights from the Global Chief Marketing Officer Study,” IBM CMO C-Suite Studies, October 2011; Natalie Zmuda, “Global Experience Rises as Prerequisite to Getting Ahead,” Advertising Age, June 10, 2012; George S. Day and Robert Malcolm, “The CMO and the Future of Marketing,” Marketing Management, Spring 2012, pp. 34-43; Marc De Swann Arons and Frank Van Den Driest, The Global Brand CEO: Building the Ultimate Marketing Machine (New York: Airstream, 2011); Marylee Sachs, The Changing MO of the CMO: How the Convergence of Brand and Reputation Is Affecting Marketers (Surry, England: Gower, 2011); Marylee Sachs, What the New Breed of CMOs Know That You Don’t (Surry, England: Gower, 2013).

2. DEFINING THE CORPORATE MISSION

An organization exists to accomplish something: to make cars, lend money, provide a night’s lodging. Over time, the mission may change to respond to new opportunities or market conditions. Amazon.com changed its mission from being the world’s largest online bookstore to aspiring to be the world’s largest online store; eBay changed from running online auctions for collectors to running online auctions of all kinds of goods; and Dunkin’ Donuts switched its emphasis from doughnuts to coffee.

To define its mission, a company should address Peter Drucker’s classic questions:13 What is our business? Who is the customer? What is of value to the customer? What will our business be? What should our business be? These simple-sounding questions are among the most difficult a company will ever face. Successful companies continuously ask and answer them.

BUSINESS DEFiNITION Companies often define themselves in terms of products: They are in the “auto business” or the “clothing business.” Market definitions of a business, however, describe the business as a customer- satisfying process. Products are transient; basic needs and customer groups endure forever. Transportation is a need: the horse and carriage, automobile, railroad, airline, ship, and truck are products that meet that need. Consider how Steelcase takes a market definition approach to its business.14

STEELCASE The world’s best-selling maker of office furniture, Steelcase describes itself as “the global leader in furnishing the work experience in office environments.” Defining its business broadly, former CEO James Hackett believes, “enabled a lot of the great insights that we had found out about work to be transferred beyond the office (and into furnishing home offices, schools and health care facilities).” Steelcase uses a 23-person research team to gain those insights and conducts interviews and surveys, films office activities, and uses sensors to measure how workers use rooms and furnishings. Firms are ordering fewer cubicles and filing cabinets, for instance, and more benches, tables, and cafe seating to free employees to brainstorm and collaborate. Hackett defines the trend as the move from an “I/Fixed” to a “We/Mobile” mentality. Increased performance is the company’s key goal. If it feels it will make workers happier and more productive, Steelcase can convince a firm to modernize and upgrade its office furniture.

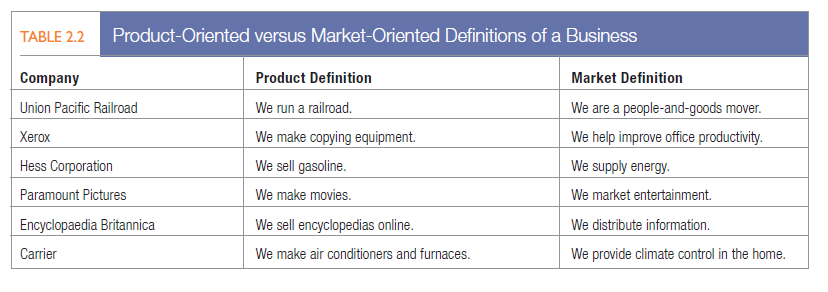

Viewing businesses in terms of customer needs can suggest additional growth opportunities. Table 2.2 lists companies that have moved from a product to a market definition of their business.

A target market definition tends to focus on selling a product or service to a current market. Pepsi could define its target market as everyone who drinks carbonated soft drinks, and competitors would therefore be other carbonated soft drink companies. A strategic market definition, however, also focuses on the potential market. If Pepsi considered everyone who might drink something to quench his or her thirst, its competition would include noncarbonated soft drinks, bottled water, fruit juices, tea, and coffee.

CRAFTING A MSSION STATEMENT A clear, thoughtful mission statement, developed collaboratively with and shared with managers, employees, and often customers, provides a shared sense of purpose, direction, and opportunity. At its best it reflects a vision, an almost “impossible dream,” that provides direction for the next 10 to 20 years. Sony’s former president, Akio Morita, wanted everyone to have access to “personal portable sound” so his company created the Walkman and portable CD player. Fred Smith wanted to deliver mail anywhere in the United States before 10:30 am the next day, so he created FedEx.

Good mission statements have five major characteristics.

- They focus on a limited number of goals. Compare a vague mission statement such as “To build total brand value by innovating to deliver customer value and customer leadership faster, better, and more completely than our competition” to Google’s ambitious but more focused mission statement, “To organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.”

- They stress the company’s major policies and values. Narrowing the range of individual discretion lets employees act consistently on important issues.

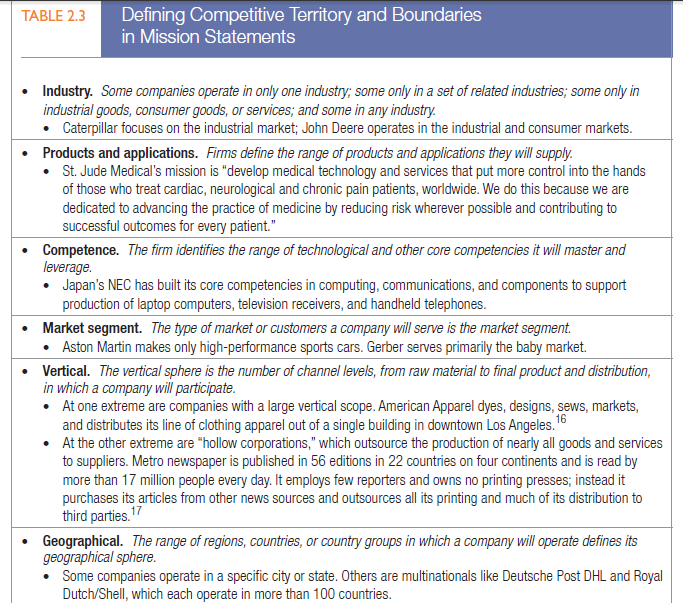

- They define the major competitive spheres within which the company will operate. Table 2.3 summarizes some key competitive dimensions for mission statements.

- They take a long-term view. Management should change the mission only when it ceases to be relevant.

- They are as short, memorable, and meaningful as possible. Marketing consultant Guy Kawasaki advocates developing three- to four-word corporate mantras—like “Enriching Women’s Lives” for Mary Kay—rather than mission statements.15

3. ESTABLISHING STRATEGIC BUSINESS UNITS

Large companies normally manage quite different businesses, each requiring its own strategy. At one time, General Electric classified its businesses into 49 strategic business units (SBUs). An SBU has three characteristics:

- It is a single business, or a collection of related businesses, that can be planned separately from the rest of the company.

- It has its own set of competitors.

- It has a manager responsible for strategic planning and profit performance, who controls most of the factors affecting profit.

The purpose of identifying the company’s strategic business units is to develop separate strategies and assign appropriate funding. Senior management knows its portfolio of businesses usually includes a number of “yesterday’s has-beens” as well as “tomorrow’s winners.” Liz Claiborne has put more emphasis on some of its younger businesses such as Juicy Couture, Lucky Brand Jeans, Mexx, and Kate Spade while selling businesses without the same buzz (Ellen Tracy, Sigrid Olsen, and Laundry).

4. ASSIGNING RESOURCES TO EACH SBU

Once it has defined SBUs, management must decide how to allocate corporate resources to each. The GE/McKinsey Matrix classified each SBU by the extent of its competitive advantage and the attractiveness of its industry. Management could decide to grow, “harvest” or draw cash from, or hold on to the business. BCG’s Growth-Share Matrix used relative market share and annual rate of market growth as criteria for investment decisions, classifying SBUs as dogs, cash cows, question marks, and stars.

Portfolio-planning models like these have largely fallen out of favor as oversimplified and subjective. Newer methods rely on shareholder value analysis and on whether the market value of a company is greater with an SBU or without it. These value calculations assess the potential of a business based on growth opportunities from global expansion, repositioning or retargeting, and strategic outsourcing.

5. ASSESSING GROWTH OPPORTUNITIES

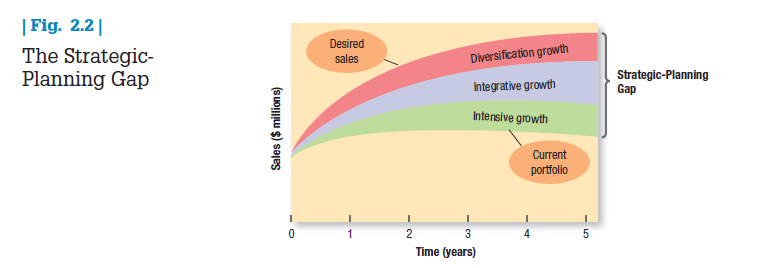

Assessing growth opportunities includes planning new businesses, downsizing, and terminating older businesses. If there is a gap between future desired sales and projected sales, corporate management will need to develop or acquire new businesses to fill it.

Figure 2.2 illustrates this strategic-planning gap for a hypothetical manufacturer of blank DVD discs called Cineview. The lowest curve projects expected sales from the current business portfolio over the next five years. The highest describes desired sales over the same period. Evidently, the company wants to grow much faster than its current businesses will permit. How can it fill the strategic- planning gap?

The first option is to identify opportunities for growth within current businesses (intensive opportunities). The second is to identify opportunities to build or acquire businesses related to current businesses (integrative opportunities). The third is to identify opportunities to add attractive unrelated businesses (diversification opportunities).

INTENSiVE GROWTH Corporate management should first review opportunities for improving existing businesses. One useful framework is a “product-market expansion grid,” which considers the strategic growth opportunities for a firm in terms of current and new products and markets.

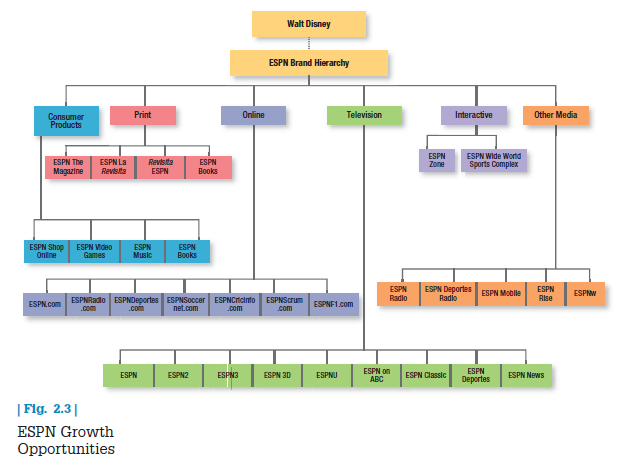

The company first considers whether it could gain more market share with its current products in their current markets, using a market-penetration strategy. Next it considers whether it can find or develop new markets for its current products, in a market- development strategy. Then it considers whether it can develop new products for its current markets with a product-development strategy. Later the firm will also review opportunities to develop new products for new markets in a diversification strategy. Consider how ESPN has pursued a variety of growth opportunities (see Figure 2.3).19

ESPN Through its singular focus on sports programming and news, ESPN grew from a small regional broadcaster into the biggest name in sports. In the early 1990s, the company crafted a well-thought-out plan: Wherever sports fans watched, read, and discussed sports, ESPN would be there. It pursued this strategy by expanding its brand and now encompasses 10 cable channels, a Web site, a magazine, a few restaurants (ESPN Zone), more than 600 local radio affiliates, original movies and television series, book publishing, a sports merchandise catalog and online store, music and video games, and a mobile service. ESPN International partly or wholly owns 47 television networks outside the United States and a variety of additional businesses that reach sports fans in more than 200 countries and territories across all seven continents. Now owned by The Walt Disney Company, ESPN contributes $9.4 billion a year in revenue, or roughly three-fourths of Disney’s total cable network revenues. But perhaps the greatest tribute to the power of its brand came from one male focus group respondent who said, “If ESPN was a woman, I’d marry her.”

So how might Cineview use these three major intensive growth strategies to increase its sales? It could try to encourage its current customers to buy more by demonstrating the benefits of using DVD discs for data storage in addition to video storage. It could try to attract competitors’ customers if it noticed major weaknesses in their products or marketing programs. Finally, Cineview could try to convince nonusers to start using blank DVD discs.

How can Cineview use a market-development strategy? First, it might try to identify potential user groups in the current sales areas. If it has been selling DVD discs only to consumer markets, it might go after office and factory markets. Second, it might seek additional distribution channels by adding mass merchandising or online channels. Third, the company might sell in new locations in its home country or abroad.

Management should also consider new-product possibilities. Cineview could develop new features, such as additional data storage capabilities or greater durability. It could offer the DVD discs at two or more quality levels, or it could research an alternative technology such as flash drives.

These intensive growth strategies offer several ways to grow. Still, that growth may not be enough, and management must also look for integrative growth opportunities.

INTEGRATiVE GROWTH A business can increase sales and profits through backward, forward, or horizontal integration within its industry. Merck formed joint ventures as far back as 1989 with Johnson & Johnson to sell over-the-counter pharmaceuticals and 1991 with DuPont to expand basic research. In 1997, Merck and Rhone-Poulenc S.A. (now Sanofi-Aventis S.A.) combined their animal health and poultry genetics businesses to form Merial Limited, a fully integrated animal health company. Finally, Merck acquired Schering-Plough in 2009.20

Horizontal mergers and alliances don’t always work out. The merger between Sears and Kmart didn’t solve either retailer’s problems.21 Nextel Communications Inc. merged with Sprint in 2005 in what Bloomberg’s financial analysts called one the worst mergers of the past 10 years, in part due to their incompatible networks.22 Consider the challenges faced by United and Continental in their merger.23

UNITED AND CONTINENTAL Airline mergers are notoriously tricky, laden with regulations and a host of potentially conflicting considerations about safety, cost, style, reliability, convenience, speed, and comfort. United’s merger with Continental made sense strategically and financially, but logistical problems seemed endless because the two airlines ran their businesses in very different ways, from boarding procedures to the way they brought planes into the gate. Even coffee was a thorny issue; United served Starbucks while Continental used a company called Fresh Brew. After extensive research, a suitable compromise was identified—a lighter fresh blend called Journeys—but customers were unimpressed until the company discovered the two airlines had different brew baskets and United’s was actually leaking water and diluting the coffee. New pillow packs were commissioned to solve the problem.

Media companies, on the other hand, have long reaped the benefits of integrative growth. Consider how NBC Universal leveraged one of its properties:24

Following the 2006 Curious George movie release via Universal Pictures, Curious George the TV show was released on PBS Kids as a joint production by Universal Studios Family Productions, Imagine Entertainment and WGBH Boston. Universal Studios Hollywood currently has an Adventures of Curious George ride where kids can “soak up the thrills of a five hundred gallon water dump and unleash thousands of flying foam balls ”

How might Cineview achieve integrative growth? The company might acquire one or more of its suppliers, such as plastic material producers, to gain more control or generate more profit through backward integration. It might acquire some wholesalers or retailers, especially if they are highly profitable, in forward integration. Finally, Cineview might acquire one or more competitors, provided the government does not bar this horizontal integration. However, these new sources may still not deliver the desired sales volume. In that case, the company must consider diversification.

DIVERSIFICATION GROWTH Diversification growth makes sense when good opportunities exist outside the present businesses—the industry is highly attractive and the company has the right mix of business strengths to succeed. From its origins as an animated film producer, The Walt Disney Company has moved into licensing characters for merchandised goods, publishing general interest fiction books under the Hyperion imprint, entering the broadcast industry with its own Disney Channel as well as ABC and ESPN, developing theme parks and vacation and resort properties, and offering cruise and commercial theatre experiences.

Several types of diversification are possible for Cineview. First, the company could choose a concentric strategy and seek new products that have technological or marketing synergies with existing product lines, though appealing to a different group of customers. It might start a compact disc manufacturing operation because it knows how to manufacture DVD discs or a flash drive manufacturing operation because it knows digital storage. Second, it might use a horizontal strategy and produce plastic DVD cases, for example, though they require a different manufacturing process. Finally, the company might seek new businesses with no relationship to its current technology, products, or markets, adopting a conglomerate strategy to consider making application software or personal organizers.

DOWNSIZING AND DIVESTING OLDER BUSINESSES Companies must carefully prune, harvest, or divest tired old businesses to release needed resources for other uses and reduce costs. To focus on its travel and credit card operations, American Express spun off American Express Financial Advisors, which provided insurance, mutual funds, investment advice, and brokerage and asset management services (it was renamed Ameriprise Financial). American International Group (AIG) agreed to sell two of its subunits—American General Indemnity Co. and American General Property Insurance Co.—to White Mountains Insurance Group as part of a long-term growth strategy to discard redundant assets and focus on its core operations.25

6. ORGANIZATION AND ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE

Strategic planning happens within the context of the organization. A company’s organization consists of its structures, policies, and corporate culture, all of which can become dysfunctional in a rapidly changing business environment. Whereas managers can change structures and policies (though with difficulty), the company’s culture is very hard to change. Yet adapting the culture is often the key to successfully implementing a new strategy.

What exactly is a corporate culture? Some define it as “the shared experiences, stories, beliefs, and norms that characterize an organization.” Walk into any company and the first thing that strikes you is the corporate culture—the way people dress, talk to one another, and greet customers.

A customer-centric culture can affect all aspects of an organization. Enterprise Rent-A-Car features its own employees in its latest “The Enterprise Way” ad campaign. Through its “Making It Right” training program, Enterprise empowers all employees to make their own decisions. One ad in the campaign, themed “Fix Any Problem,” reinforces how any local Enterprise outlet has the authority to take actions to maximize customer satisfaction.26

7. MARKETING INNOVATION

Innovation in marketing is critical. Imaginative ideas on strategy exist in many places within a company. Senior management should identify and encourage fresh ideas from three generally underrepresented groups: employees with youthful or diverse perspectives, employees far removed from company headquarters, and employees new to the industry. Each group can challenge company orthodoxy and stimulate new ideas.

British-based Reckitt Benckiser has been an innovator in the staid household cleaning products industry by generating 35 percent of sales from products under three years old.27 Its multinational staff is encouraged to dig deep into consumer habits and is well rewarded for excellent performance. Slovenia-based Krka—makers of prescription pharmaceuticals, non-prescription products and animal health products—aims to generate more than 40 percent of its total sales from new products.28 “Marketing Insight: Creating Innovative Marketing” describes how some leading companies approach innovation.

Firms develop strategy by choosing their view of the future. The Royal Dutch/Shell Group has pioneered scenario analysis, which develops plausible representations of a firm’s possible future using assumptions about forces driving the market and different uncertainties. Managers think through each scenario with the question, “What will we do if it happens?,” adopt one scenario as the most probable, and watch for signposts that might confirm or disconfirm it.29 Consider the strategic challenges faced by the movie industry.30

MOVIE INDUSTRY Netflix and the Internet started a decline in DVD sales that began in 2007 and has not stopped. The emergence of Redbox kiosks renting movies for $1 a day added yet another threat to the movie business and DVD sales. Film studios clearly need to prepare for the day when films are primarily sold not through physical distribution but through satellite and cable companies’ video-on-demand services. Although studios make 70 percent on a typical $4.99 cable viewing versus 30 percent on the sale of a DVD, sales of DVDs still generate 70 percent of a film’s profits. To increase electronic distribution without destroying their DVD business, studios are experimenting with new approaches. Some, such as Warner Bros., are releasing a DVD at the same time as online and cable versions of a movie. Disney cross-promotes its parent-friendly films at its theme parks, on its TV channels, and in its stores. Warner has entered the video game business (such as with Dark Knight Batman) in hopes of generating additional revenue on its movie characters. Warner Interactive typically spends $30 million to $40 million to make its games and generated close to $1 billion in sales in 2011. Film studios are considering all possible scenarios as they rethink their business model in a world where the DVD is no longer king.

8. MARKETING insight Creating Innovative Marketing

When IBM surveyed top CEOs and government leaders about their priorities, business-model innovation and coming up with unique ways of doing things scored high. IBM’s own drive for business-model innovation led to much collaboration, both within IBM and externally with companies, governments, and educational institutions. Then-CEO Samuel Palmisano noted how the breakthrough Cell processor, based on the company’s Power architecture, would not have happened without collaboration with Sony and Nintendo, as well as competitors Toshiba and Microsoft.

Procter & Gamble (P&G) has made it a goal for 50 percent of new products to come from outside its labs—from inventors, scientists, and suppliers whose new-product ideas can be developed in-house. Mark Benioff, CEO and co-founder of Salesforce.com, believes the key to i nnovation is the ability to adapt. While the company spent years relying on disruptive ideas to come from within, it acquired two firms for $1 billion because it “couldn’t afford to wait” and has purchased 24 firms in total. As Benioff notes, “Innovation is a continuum. You have to think about how the world is evolving and transforming. Are you part of the continuum?”

Business guru Jim Collins’s research emphasizes the importance of systematic, broad-based innovation: “Always looking for the one big breakthrough, the one big idea, is contrary to what we found: To build a truly great company, it’s decision upon decision, action upon action, day upon day, month upon month. . . . It’s cumulative momentum and no one decision defines a great company.” Collins cites Walt Disney in theme parks and Walmart in retailing as examples of companies that were successful by executing a big idea brilliantly over a long period of time.

To find breakthrough ideas, some companies immerse a range of employees in solving marketing problems. Samsung’s Value Innovation Program (VIP) isolates product development teams of engineers, designers, and planners with a timetable and end date in the company’s center just south of Seoul, Korea, while 50 specialists help guide their activities. To help make tough trade-offs, team members draw “value curves” that rank attributes such as a product’s sound or picture quality on a scale from 1 to 5. To develop a new car, BMW mobilizes specialists in engineering, design, production, marketing, purchasing, and finance at its Research and Innovation Center or Project House.

Companies like Facebook and Google kickstart the creative problem-solving process by using the phrase, “How might we?” Tim Brown, CEO of IDEO, says IDEO asks “how might we” with each design challenge. “The ‘How’ part assumes there are solutions out there—it provides creative confidence,” Brown said. “The ‘Might’ part says we can put ideas out there that might work or might not—either way, it’s OK. And the ‘We’ part says we’re going to do it together and build on each other’s ideas.”

Sources: Steve Hamm, “Innovation: The View from the Top,” BusinessWeek, April 3, 2006, pp. 52-53; Jena McGregor, “The World’s Most Innovative Companies,” BusinessWeek, April 24, 2006, pp. 63-74; Rich Karlgard, “Digital Rules,” Forbes, March 13, 2006, p. 31; Jennifer Rooney and Jim Collins, “Being Great Is Not Just a Matter of Big Ideas,” Point, June 2006, p. 20; Moon Ihlwan, “Camp Samsung,” BusinessWeek, July 3, 2006, pp. 46^7; Mohanbir Sawhney, Robert C. Wolcott, and Inigo Arroniz, “The 12 Different Ways for Companies to Innovate,” MIT Sloan Management Review (Spring 2006), pp. 75-85; Victoria Barret, “Why Salesforce.com Ranks #1 on Forbes Most Innovative List,” Forbes, September 2012; Warren Berger, “The Secret Phrase Top Innovators Use,” HBR Blog Network, September 17, 2012.

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

Hello.This article was really motivating, especially because I was searching for thoughts on this subject last Sunday.