1. ANALYSING THE CURRENT SITUATION AND PROJECTING FORWARD

1.1. Organisation, behaviour and culture

It is in this area that more choice of techniques is available, and the possibilities include the use of questionnaires to staff (see www.pearsoned.co.uk/torrington HRP Exercise, 3.1, note 7.), interviews with staff and managerial judgement. Focus groups are an increasingly popular technique where, preferably, the Chief Executive meets with, say, 20 representative staff from each department to discuss their views of the strengths and weaknesses of the organisation, and what can be done to improve. These approaches can be used to provide information on, for example:

- Motivation of employees.

- Job satisfaction.

- Organisational culture.

- The way that people are managed.

- Attitude to minority groups and equality of opportunity.

- Commitment to the organisation and reasons for this.

- Clarity of business objectives.

- Goal-focused and other behaviour.

- Organisational issues and problems.

- What can be done to improve.

- Organisational strengths to build on.

Turnover figures, performance data, recruitment and promotion trends and characteristics of employees may also shed some light on these issues.

Data relating to current formal and informal systems, together with data on the structure of the organisation, also need to be collected, and the effectiveness, efficiency and other implications of these need to be carefully considered. Most data will be collected from within the organisation, but data may also be collected from significant others, such as customers, who may be part of the environment.

1.2. Current and projected employee numbers and skills (employee supply)

Current employee supply can be analysed in both individual and overall statistical terms. To gain an overview of current supply the following factors may be analysed either singly or in combination: number of employees classified by function, department, occupation job title, skills, qualifications, training, age, length of service, performance appraisal results. (See www.pearsoned.co.uk/torrington HRP Exercise, 3.1, note 8.)

Forecasting employee supply is concerned with predicting how the current supply of employees will change, primarily how many will leave, be internally promoted or transferred. These changes are forecast by analysing what has happened in the past, in terms of staff retention and/or movement, and projecting this into the future to see what would happen if the same trends continued. The impact of changing circumstances would also need to be taken into account when projecting analyses forward. Bell (1989)

provides an extremely thorough coverage of possible analyses, on which this section is based. Behavioural aspects are also important, such as investigating the reasons why staff leave, the criteria that affect promotions and transfers and changes in working conditions and in HR policy. Analyses fall broadly into two categories: analyses of staff leaving, and analyses of internal movements. The following calculations are the most popular forms of analysing staff leaving the organisation.

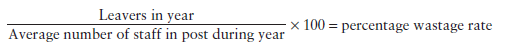

1.3. Annual labour turnover index

The annual labour turnover index is sometimes called the percentage wastage rate, or the conventional turnover index. This is the simplest formula for wastage and looks at the number of staff leaving during the year as a percentage of the total number employed who could have left.

This measure has been criticised because it gives only a limited amount of information. If, for example, there were 25 leavers over the year, it would not be possible to determine whether 25 different jobs had been left by 25 different people, or whether 25 different people had tried and left the same job. Length of service is not taken into account with this measure, yet length of service has been shown to have a considerable influence on leaving patterns, such as the high number of leavers at the time of induction.

Stability index

The stability index is based on the number of staff who could have stayed throughout the period. Usually, staff with a full year’s service are expressed as a percentage of staff in post one year ago.

![]()

(See www.pearsoned.co.uk/torrington HRP Exercise, 3.1, note 10.)

This index, however, ignores joiners throughout the year and takes little account of length of service.

Cohort analysis

A cohort is defined as a homogeneous group of people. Cohort analysis tracks what happens as some people leave a group of people with very similar characteristics who all joined the organisation at the same time. Graduates are an appropriate group for this type of analysis. A graph showing what happens to the group can be in the form of a survival curve or a log-normal wastage curve, which can be plotted as a straight line and can be used to make predictions. The disadvantage of this method of analysis is that it cannot be used for groups other than the specific group for which it was originally prepared. The information has also to be collected over a long time-period, which produces problems of availability and reliability of data.

Half-life

The half-life is a figure expressing the time taken for half the cohort to leave the organisation. The figure does not give as much information as a survival curve, but it is useful as a summary and as a method of comparing different groups.

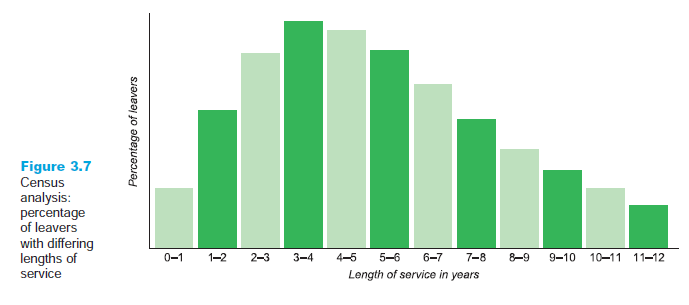

Census method

The census method is an analysis of leavers over a reasonably short period of time – often over a year. The length of completed service of leavers is summarised by using a histogram, as shown in Figure 3.7. (See www.pearsoned.co.uk/torrington HRP Exercise, 3.1, note 11.)

Retention profile

Staff retained, that is those who remain with the organisation, are allocated to groups depending on the year they joined. The number in each year group is translated into a percentage of the total number of individuals who joined during that year.

We move now to methods of analysing internal movements. These focus on either overall analyses of movement patterns in the organisation or succession planning, which has a more individual emphasis.

Analyses of internal movements

Movement patterns

Age and length of service distributions can be helpful to indicate an overall pattern of problems that may arise in the future, such as promotion blocks. They need to be used in conjunction with an analysis of previous promotion patterns in the organisation. (See www.pearsoned.co.uk/torrington HRP Exercise, 3.1, note 12.) An alternative is a stocks and flows analysis of the whole organisation or a part of it, such as a department.

The model is constructed to show the hierarchy of positions and the numbers employed in each. Numbers moving between positions, and in and out of the organisation over any time-period, can be displayed. The model displays visually promotion and lateral move channels in operation, and shows what happens in reality to enable comparison to be made with the espoused approach, but users need to recognise, and work within, the limitation that the structure of jobs will change more rapidly than in the past.

Individual succession analysis

On an individual basis many organisations pay special attention to analysing the likely succession into key roles of current high-potential employees. Originally the process was an informal approach to promotion with a short-term focus on who would be able to replace senior people if they left suddenly, so that disruption and dislocation were minimised (see, for example, Huang 2001). Such analyses have increasingly involved a range of proactive approaches to developing successors and talent in general, and we say more about this in the section on plans below.

2. RECONCILIATION, DECISIONS AND PLANS

We have already said that, in reality, there is a process of continuous feedback between the different stages of human resource planning activities, as they are all interdependent. On the soft side (organisation, behaviour and culture) there is a dynamic relationship between the future vision, environmental trends and the current position. Key factors to take into account during reconciliation and deciding on action plans are the acceptability of the plans to both senior managers and other employees, the priority of each plan, key players who will need to be influenced and the factors that will encourage or be a barrier to successful implementation.

On the hard side, feasibility may centre on the situation where the supply forecast is less than the demand forecast. Here, the possibilities are to:

- alter the demand forecast by considering changes in the utilisation of employees (such as training and productivity deals, or high-performance teams): by using different employees with higher skills; employing staff with insufficient skills and training them immediately; or outsourcing the work;

- alter the supply forecast by, say, reducing staff turnover, delaying retirement, or widening the supply pool by including EU nationals;

- change the company objectives, as lack of human resources will prevent them from being achieved in any case. Realistic objectives need to be based on the resources that are, and are forecast to be, available either internally or externally.

When the demand forecast is less than the internal supply forecast in some areas, the possibilities are to:

- consider and calculate the costs of overemployment over various timespans;

- consider the methods and cost of losing staff;

- consider changes in utilisation: work out the feasibility and costs of retraining, redeployment and so on;

- consider whether it is possible for the company objectives to be changed. Could the company diversify, move into new markets, etc.?

We have also noted the interrelationship between the soft and the hard aspects of planning. For example, the creation of high-performance teams may have implications for different staffing numbers, a different distribution of skills, alternative approaches to reward and a different management style. The relocation of a supplier’s staff on to the premises of the company that they supply, in order to get really close to this customer, could have implications for relocation, recruitment, skills required and culture encouraged. The development of a learning organisation may have implications for turnover and absence levels, training and development provision, culture encouraged and approach to reward.

Once all alternatives have been considered and feasible solutions decided, specific action plans can be designed covering all appropriate areas of HRM activity. Whilst these have been grouped in separate sections, below, there is clearly potential overlap between the groups.

2.1. Human resource supply plans

Plans may need to be made concerning the timing and approach to recruitment or downsizing. For example, it may have been decided that in order to recruit sufficient staff, a public relations campaign is needed to promote a particular company image. Promotion, succession, transfer and redeployment and redundancy plans are also relevant here. Plans for the retention of those aged over 50 and flexible retirement plans are a key theme at present and we consider some examples of these in Chapter 24 on Equal opportunities and diversity. Increasingly there is the need to focus on plans for the development and retention of the talent pool, and given their continuing high profile we look at succession plans in more detail below.

Succession plans

From the 1980s onwards the more proactive and formal approaches to succession included careful analysis of the jobs to be filled, a longer-term focus, developmental plans for individuals who were identified as successors, and the possibility of cross-functional moves. This approach was typically applied to those identified as having high potential, and was generally centred on the most senior positions. Larger organisations would produce tables of key jobs on which were named immediate successors, probable longer- term successors and potential longer-term successors, all with attached development plans. Alternatively, high-potential individuals were identified with likely immediate moves, probable longer-term moves and possible longer-term moves. However, as Hirsh

(2000) points out, this model is appropriate to a stable environment and career structure, and the emphasis in current succession planning has changed yet again. The concentration is now on the need to build and develop a pool of talent, without such a clear view of how the talent will be used in the future, and this is associated with the current high profile of ‘talent management’, brought into focus by McKinsey’s ‘war for talent’ (1997). Developing a talent pool is a more dynamic approach and fits well with the resource- based view of the firm. While the link to business strategy is emphasised, there is more recognition of individual aspirations and a greater opportunity for people to put themselves forward to be considered for the talent pool. Developing talent at different leadership levels in the organisation is considered important, and current debates focus on the definition of talent in terms of what it means and to whom it applies. Warren (2006) discusses the issue of inclusivity and whether organisations should focus on an elite of high-performing, high-potential individuals, or whether inclusivity should be more broadly defined. Much greater openness in succession planning is encouraged, and more consideration is given to the required balance between internal talent development and external talent. Simms (2003) provides an interesting debate on these issues, which is provided as Case study 3.2 at www.pearsoned.co.uk/torrington. Talent management is most closely associated with development activities and we return to this topic in Chapter 16 on Strategic aspects of development.

2.2. Organisation and structure plans

Organisation and structure plans may concern departmental existence, remit and structure and the relationships between departments. They may also be concerned with the layers of hierarchy within departments and the level at which tasks are done, and the organisational groups within which they are done. Changes to organisation and structure will usually result in changes in employee utilisation.

2.3. Employee utilisation plans

Any changes in utilisation that affect human resource demand will need to be planned. Some changes will result in a sudden difference in the tasks that employees do and the numbers needed; others will result in a gradual movement over time. Other plans may involve the distribution of hours worked, for example the use of annual hours contracts; or the use of functional flexibility where employees develop and use a wider range of skills. There are implications for communications plans as the employees involved will need to be consulted about the changes and be prepared and trained for what will happen. There will be interconnections with supply plans here: for example, if fewer employees will be needed, what criteria will be used to determine who should be made redundant and who should be redeployed and retrained, and in which areas?

2.4. Learning and development plans

There will be development implications from both the human resource supply and the utilisation plans. The timing of development can be a critical aspect. For example, training for specific new technology skills loses most of its impact if it is done six months before the equipment arrives. If the organisation wishes to increase recruitment by promoting the excellent development that it provides for employees, then clear programmes of what will be offered need to be finalised and resourced so that these can then be used to entice candidates into the organisation. If the organisation is stressing customer service or total quality, then appropriate development will need to be carried out to enable employees to achieve this.

2.5. Performance management and motivation plans

These plans may include the development or renewal of a performance management system; and ensuring that employees are assessed on objectives or criteria that are key to organisational success, and which may then be linked to reward. They may also include setting performance and quality standards; culture change programmes aimed at encouraging specified behaviour and performance; or empowerment or career support to improve motivation.

2.6. Reward plans

It is often said that what gets rewarded gets done, and it is key that rewards reflect what the organisation sees as important. For example, if quantity of output is most important for production workers, bonuses may relate to number of items produced. If quality is most important, then bonuses may reflect reject rate, or customer complaint rate. If managers are only rewarded for meeting their individual objectives there may be problems if the organisation is heavily dependent on teamwork.

2.7. Employee relations plans

These plans may involve unions, employee representatives or all employees. They would include any matters which need to be negotiated or areas where there is the opportunity for employee involvement and participation.

2.8. Communications plans

The way that planned changes are communicated to employees is critical. Plans need to include not only methods for informing employees about what managers expect of them, but also methods to enable employees to express their concerns and needs for successful implementation. Communications plans will also be important if, for example, managers wish to generate greater employee commitment by keeping employees better informed about the progress of the organisation.

Once the plans have been made and put into action, the planning process still continues. It is important that the plans be monitored to see if they are being achieved and if they are producing the expected results. Plans will also need to be reconsidered on a continuing basis in order to cope with changing circumstances.

Source: Torrington Derek, Hall Laura, Taylor Stephen (2008), Human Resource Management, Ft Pr; 7th edition.

Great weblog here! Also your website so much up fast! What host are you the use of? Can I get your associate link in your host? I desire my website loaded up as fast as yours lol