1. THE FUTURE DEMAND FOR WORKERS

If current trends are maintained we can expect to see continued increases, year on year, in the number of jobs being created by British organisations. In 2006 there were 37.1 million people of working age in the UK, of whom 30.8 million were in work. Around 1.5 million were unemployed and actively seeking work, while a further 7.9 million people of working age were defined as being ‘economically inactive’ (ONS 2006a). The total number of jobs has grown steadily in recent years to reach its current peak of 26.7 million. The figure decreased during the recessions of the early 1980s and early 1990s, but the long-term trend has been upwards for over sixty years.

Importantly, this increase in the amount of employment in the UK has occurred at a time when many major industries have seen the introduction of labour-saving technologies and when millions of jobs have effectively been ‘exported’ to developing countries where labour costs are much cheaper. Major industrial restructuring has occurred, yet the demand for labour over the long term has increased steadily. Provided the economy continues to grow, we can thus expect to see further increased demand for people on the part of employers over the coming decade.

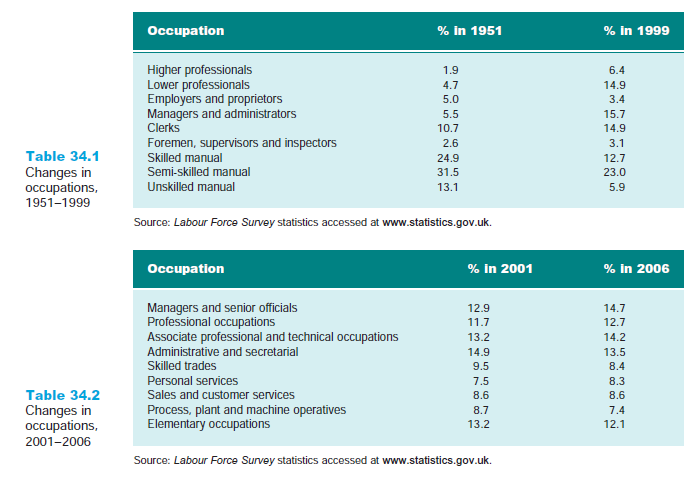

But what sort of skills will employers be looking for? Here too long-term trends paint a clear picture which there is every reason to believe will continue for the foreseeable future. The official method used to classify occupations in the UK was changed in 1999, so it is not possible to make a precise comparison of today’s figures with those produced by government statisticians before then. Nonetheless an obvious long-term pattern can be seen in the two sets of statistics presented in Tables 34.1 and 34.2. These show a pronounced switch occurring over a long period of time, and continuing strongly in more recent years, away from skilled, semi-skilled and unskilled manual work towards jobs which require higher-level and more specialised skills. The major growth areas have long been in the professional, technical and managerial occupations.

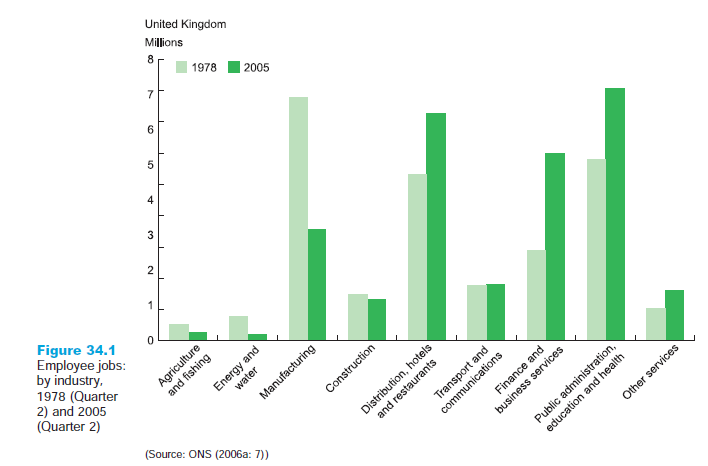

The change in the occupational profile of the UK workforce has largely been driven by the revolutionary shift that has occurred in the nature of our industries during the past thirty years. In 1978, which was the first year that data was collected on employment by sector, seven million people worked in manufacturing and a further one and a half million in the energy, water, farming and fishing industries. These have all hugely declined since then. Manufacturing now employs only three million (12 per cent of all jobs). Agriculture and fishing account for just 200,000 jobs; energy and water for fewer still (see Figure 34.1). The big growth areas have been in retailing, distribution, hotels and restaurants, finance, business services, public administration, education and health. Employment in the financial services sector has grown especially quickly, more than doubling since 1978.

In the most recent years the biggest growth areas in terms of jobs have been in the public sector. Public sector employment fell during the 1990s. Having peaked at 5.9 million in 1991, it reached a ‘low point’ of 5.1 million in 1998 before climbing back to 5.9 million again. Over 300,000 new jobs have been created in the NHS since 1998 and over 200,000 in education. The expansion of local and central government has led to the creation of 128,000 jobs, a further 45,000 being created in the police service (ONS 2006a, p. 26). Another major employment trend since the 1970s has been a substantial growth in the proportion of people working in small businesses. The small firms sector now employs 55 per cent of the UK workforce.

One of the most vigorously contested debates among labour market economists concerns the nature of the skills that employers will be looking for in the future, a debate that has very important implications for government education policy, which, as a result, is itself controversial (see Grugulis et al. 2004). In recent years a highly influential group has argued that in the future economies such as the UK’s will see a speeding up of the trends identified above. Influenced by figures such as Manuel Castells of Berkeley University in California, it has become common for policymakers to believe that a ‘new economy’ is rapidly developing which will increasingly be dominated by companies which are ‘knowledge-intensive’ in nature. According to this ‘upskilling thesis’, lower- skilled jobs will be rarer and rarer in industrialised countries. Because they can be done far more cheaply in developing economies, they will increasingly be exported overseas.

It follows that the governments such as the UK’s should prepare the workforce as best it can for the challenges of a ‘high-skill, high-wage economy’ in which those who do not have a relevant higher education are going to struggle to make a living. Hence we see the rapid expansion of universities, heavy investment in schools and the provision of all manner of schemes designed to equip unemployed people with new skills.

Critics of Castells tend to look to the writings of a very different American academic guru figure – Harry Braverman. His theories derive from a Marxian perspective as well as from observations of the activities of corporations in the 1960s and 1970s. This contrasting ‘deskilling thesis’ argues that businesses competing in capitalist economies will always look for ways of cutting their labour costs, and that they do this in part by continually reducing the level of skills required by the people they employ. It follows that, far from leading to a demand for higher-level skills and knowledge, the advent of an economy based on information and communication technologies will over time reduce such demand.

Both schools draw on widely documented trends to back up their positions. The upskillers draw attention to the fact that the major growth areas in labour demand are in the higher-skilled occupational categories. Demand for graduates is increasing, demand for lower-skilled people is less strong, and is decreasing in some industries. They also draw attention to the emergence of skills shortages in many industries as employers find it steadily harder to recruit people with the abilities and experience they need.

By contrast, the downskillers draw attention to the growth of call-centre-type operations which use technology to reduce the amount of knowledge and expertise required by customer services staff, and to the increasing use of bureaucratic systems which reduce the number of situations in which people have a discretion to make decisions. They also point to the strong growth in industries such as retailing and hotels which are characterised by employment of people who need only be low skilled and who are relatively low paid. They thus forecast a situation in which the workforce is heavily overqualified and in which graduates are increasingly employed in jobs for which no degree is necessary. They also argue that many of the ‘skills’ that employers say are in short supply are not in fact ‘skills’ at all, but are merely ‘attributes’ or ‘characteristics’. The target here is an evolving business language that refers to ‘communication skills’, ‘interpersonal skills’, ‘teamworking skills’, ‘problem-solving skills’ and ‘customerhandling skills’. These, it is argued, have nothing whatever to do with a knowledge- based economy and cannot be gained through formal education.

As with all debates that concern the likely future direction of society, it is difficult to reach firm conclusions about this debate. However, in truth what appears to be

happening is that we are seeing the emergence of an ‘hourglass’ occupational structure in the UK in which half of the jobs are of the ‘high-skill/high-pay’ variety, and the other half are ‘low skill/low pay’ (Grugulis et al. 2004: 6). The metaphor of the hourglass was originally advanced by Nolan (2001). But it has been popularised and expanded in the highly influential article by Goos and Manning (2003) entitled ‘McJobs and Macjobs: the growing polarisation of jobs in the UK’. What seems to be happening is the following:

- Increasing numbers of people are being employed in relatively highly paid, secure, professional and managerial occupations in the finance, private services and public sectors.

- Lower-skilled jobs in manufacturing along with many lower-paid clerical and administrative roles are being ‘exported’ to countries in Eastern Europe and South East Asia where cheaper labour is readily available.

- But, at the same time, the growing number of higher-paid people are using their disposable income to purchase services which cannot be provided from overseas. Hence there is a simultaneous and rapid growth in demand for hairdressers, beauticians, restaurant workers, and people to work in the media, tourist and entertainment- oriented industries.

- There also remains a great demand for, and shortage of, some groups of skilled workers – plumbers, builders, decorators, etc., whose jobs also, by their nature, cannot be so easily exported.

For the foreseeable future, therefore, we are likely to see growth in demand both for people who have gained a higher education or who have specialised higher-level skills and for people who have strong interpersonal skills (or attributes) to work in the expanding personal services sector. From a public policy point of view, this means that government is broadly correct to put more investment into higher education, but that it is equally important to make available high-quality, specialised forms of vocational education so that the future needs of all industrial sectors are properly provided for. This latter area is one in which the UK has been conspicuously weaker than other European countries for many years.

2. THE FUTURE SUPPLY OF WORKERS

The UK population currently stands at 59.8 million. This accounts for 13 per cent of the European Union population, eight per cent of the total European population and just under one per cent of the world’s total population. Unlike that of most European countries, the UK population is currently growing (Jeffries 2005). This is for two reasons:

- Birth rates currently exceed death rates. Each year approximately 700,000 babies are born in the UK, while 615,000 people die – a net gain of 85,000 people.

- Each year it is estimated that around 150,000 more people migrate into the country than emigrate out of it. Total immigration is now in excess of half a million a year.

The population is therefore growing at a rate of nearly a quarter of a million people each year (ONS 2006b). Official estimates state that the total UK population will reach 65 million by 2050, but this figure will be reached a good deal sooner if current levels of immigration continue. This upward trend in the UK population represents a reversal of the position in the in the 1970s and early 1980s – a period of substantial net emigration and relatively low birth rates.

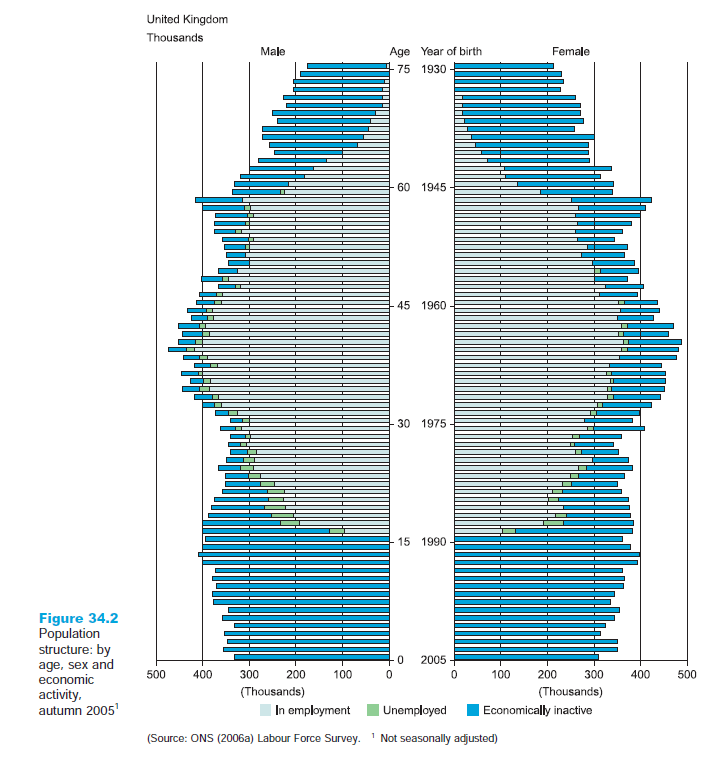

The birth rate increased substantially after the Second World War and continued at relatively high levels until the late 1960s. Over a million babies were born at the peak in 1964. This created the large ‘baby boom’ generation who are now in their forties and fifties. From 1964 onwards the UK saw a sharp decline in its birth rate, which reached a low point in 1977 when only 657,000 babies were born (i.e. fewer than the number of deaths). This was due in part to the relatively low number of births in the country in the war years (1939-45), in part to the wide availability of the contraceptive pill and abortion, and partly to changes in social attitudes leading to later marriages. The downward trend was reversed somewhat in the 1980s as the baby boomers had children, but fertility rates remain at relatively low levels historically. As a result of these patterns, we have an ageing population. There are many more people in the UK in their forties and fifties than there are in their twenties and thirties (see Figure 34.2).

This will mean that there are many more retired people in the future than there are at present, but at the same time the number of adults of working age is projected to increase rather than decrease. Official estimates state that there will be 40.5 million people who are over school leaving age and below retirement age in 2020 as a result of continued net immigration and the equalisation of male and female state pension ages at 65 from 2010. The average age of this group will increase substantially because there will be a higher proportion of older people in the workforce and because younger people are projected to choose to stay on in full-time education for longer, on average, than they currently do (Smith et al. 2005). We can thus conclude with a degree of confidence both that the supply of labour will increase in the coming two decades and that the profile of the workforce will age significantly.

However, there are important regional differences that it is important to note. The structure, density and growth of the population are by no means likely to be uniform across the whole country. The highest concentrations of older people, for example, are in the resort towns along the south and eastern coasts. Christchurch in Dorset is officially the ‘oldest’ place in the UK where 33.2 per cent are entitled to draw a state pension. By contrast, pensioners are few and far between in inner London. Tower Hamlets boasts the lowest proportion (only 9.8 per cent), but the numbers are also low in some commuter towns close to London and in cities with large student populations.

The highest concentrations of children are found in Northern Ireland where fertility rates are much higher than elsewhere in the country, while young adults are concentrated in university towns and cities, reflecting the fact that there are now 1.4 million full-time students in the UK. As far as England is concerned, between the 1930s and 2001 the major trend was a movement of people from the north of the country to the south, the southern regions gaining 30,000 people a year on average during this period. Since 2001 there has been an apparent reversal of this long-term trend, the north gaining 35,000 people per year at the expense of the south (Champion 2005). However, as a result of migration and falling fertility rates the populations of Scotland and Wales are both falling. In both countries there are considerably more deaths than births each year and relatively high levels of net emigration.

We can also predict with some certainty that there will be greater diversity among the workforce in terms of ethnicity and national origin as a result of net immigration.

All around the world international migration is increasing. As far as the UK is concerned this means that the long-term trend is towards greater levels of both emigration and immigration (Horsfield 2005). Until the early 1990s the UK had been broadly in balance as far as international migration was concerned for around twenty years. Indeed, for much of the 1970s and during the early 1980s more people left the UK each year than entered it. Since 1993 this trend has changed. Every year there are now substantially more immigrants than emigrants, a gap which widens year on year. People leaving the UK tend to be older on average than the new arrivals. Many leave in order to retire in sunnier climes, while others seek new opportunities in Australasia, the USA, Canada and EU countries. A fair proportion of annual emigration each year involves people who were born overseas returning to their countries of origin, for example following a period studying in a UK university. Historically the main source of immigrants into the UK has been from new Commonwealth countries such as India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and from the Caribbean. However, more recently we have seen a substantial growth in people arriving from other developing countries (such as Somalia) and especially from the countries which joined the European Union in May 2004 (i.e. Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Cyprus and the Baltic states).

As a result of net immigration the proportion of the UK population which was born overseas increases each year, the vast majority of these people being of working age (Randall and Salt 2005). At the time of the 2001 census just under five million UK residents had been born overseas. This represents 8.3 per cent of the population. This is a great deal higher than was the case at the time of previous censuses. In 1991 the figure was 6.7 per cent, and in 1951 only 4.2 per cent. Here too, however, there is considerable regional variation. Forty-eight per cent of immigrants arriving in the UK settle in London and the south east of England, the largest numbers settling in inner London. The London borough of Brent boasts the highest proportion of foreign-born residents (46.6 per cent). By contrast, the lowest levels (under 3 per cent) are found in the English- Scottish border regions.

If current trends continue the supply of labour across the UK as a whole should be sufficient to meet the growing demand for labour. Chronic skills shortages will be avoided provided government and employers continue to invest in the education and development of people. Importantly, in these respects the UK is a great deal better placed than many of its competitor countries where the population is falling and is ageing at a far faster rate than is the case in Britain. Fertility rates in many southern and eastern European countries have now fallen well below 1.5, meaning that each couple produces on average fewer than 1.5 children. A fertility rate of 2.1 is required to maintain a stable population, yet it is 1.32 in Germany, 1.28 in Italy, 1.27 in Spain and only 1.26 in Poland (United Nations 2005). In the UK immigration allows the maintenance of steady population growth, despite historically low fertility rates (1.66 in 2006). This is in contrast to the position of many countries where immigration rules are more restrictive or where low wages and relatively high unemployment make them less attractive to economic migrants.

The statistics suggest, however, that employers in many regions will continue to face some skills shortages. Provided unemployment remains relatively low, this will tend to push wage rates up beyond the rate of price inflation. The result, as has been the case for the past fifteen years, will be greater pressure on organisations to improve labour productivity by reorganising, merging to achieve economies of scale and outsourcing activities where they can be supplied more efficiently by external providers. It will also be necessary for employers willingly to employ more older people than they have tended to be accustomed to doing. Indeed, in order to meet their demand for labour it is likely that organisations are going to have to target older groups and take steps to make employment attractive to them. There are three distinct groups who have not traditionally found themselves to be in great demand by recruiters:

- people over the age of fifty who are still working,

- people who have taken early retirement/redundancy,

- people who are over the state retirement age.

In the case of the first group, traditional full-time jobs will be sought. The others are more likely to be looking for part-time work or some other form of flexible working. Research strongly suggests that most people have a preference for phased retirement as opposed to full-time work until a retirement day and then leisure (HSBC 2006). Employers who can provide flexibility of this kind will be in a far stronger position to compete for the services of older workers than competitors who do not. Another consequence of an ageing population will be the presence among younger employees of more people with responsibility for caring for elderly relatives. Attracting and retaining them will also require flexible working options.

Aside from flexibility, the other major element that needs to be in place in order to attract and retain older people is a culture which fully respects and values their contribution. A great deal of research has been carried out in recent years looking at attitudes to older workers among managers and younger employees. The conclusion is that people commonly stereotype older workers, just as they tend to stereotype young workers. Older workers tend to be seen as being reliable, stable, mature and experienced, but also as difficult to train, resistant to change, over-cautious, poor with technology, slow and prone to ill health. Organisations which are serious about employing more older people will need to tackle such stereotyping and to ensure that opportunities for development are provided for people of all ages.

However, at the same time, employers need to recognise that people do change as they age and do contribute different qualities than younger colleagues. They thus need to be managed somewhat differently from an HR perspective. It will be necessary, for example, to tailor reward packages to suit the needs of older workers as well as younger ones. Clearly this will include pension arrangements, but may also incorporate other benefits which older employees value more than younger employees such as health insurance.

Organisations often seek a workforce which reflects its core target market. This is particularly true of creative and media industries which need younger employees to ensure that they are in touch with the needs, aspirations and concerns of people in the key 18-30 group. This is a major source of age discrimination in the labour market which is likely, over time, to change. Instead of seeking employees who match their consumers by age, employers will want people of any age who reflect the values and attitudes of more broadly-aged target markets.

The changes to HR practice required as a result of increased numbers of workers from overseas are less profound but equally important. The key here is to make sure that the organisation both gains and retains a reputation for fairness in its labour markets. Once an organisation is perceived to be prone to acting in a discriminatory fashion towards members of ethnic minorities or migrant workers, the reputation is hard to shake off, making it harder to recruit and retain a skilled workforce. In this area perceptions of managers about the fairness of their policies and practices is irrelevant. The perception of the target labour market is all that matters, so we can expect to see organisations in the future ‘bending over backwards’ to ensure not just that they are committed to equal opportunities and diversity, but that they are seen to be too.

Source: Torrington Derek, Hall Laura, Taylor Stephen (2008), Human Resource Management, Ft Pr; 7th edition.

It’s arduous to find educated folks on this topic, but you sound like you already know what you’re speaking about! Thanks