When managers are accused of lying, cheating, or stealing, the blame is usually is placed on the individual or on the company situation. Most people believe that individuals make eth- ical choices because of individual integrity, which is true, but it is not the whole story. Ethi- cal or unethical business practices usually reflect the values, attitudes, beliefs, and behavior patterns of the organizational culture; thus, ethics is as much an organizational as a personal issue.20 Let’s examine how both the manager and the organization shape ethical decision making,21 as shown in the Benchmarking Box.

1. THE MANAGER

Managers bring specific personality and behavioral traits to the job. Personal needs, family influence, and religious background all shape a manager’s value system. Specific personality characteristics, such as ego strength, self-confidence, and a strong sense of independence, may enable managers to make ethical decisions.

One important personal trait is the stage of moral development.22 A simplified version of one model of personal moral development is shown in Exhibit 4.2. At the preconventional level, individuals are concerned with external rewards and punishments and obey authority to avoid detrimental per- sonal consequences. In an organizational context, this level may be associated with managers who use an autocratic or coercive leadership style, with employ- ees oriented toward dependable accom- plishment of specific tasks.

At level two, called the conventional level, people learn to conform to the ex- pectations of good behavior as defined by colleagues, family, friends, and soci- ety. Meeting social and interpersonal obligations is important. Work group collaboration is the preferred manner for accomplishing organizational goals, and managers use a leadership style that en- courages interpersonal relationships and cooperation.

At the postconventional, or principled, level, individuals are guided by an in- ternal set of values and standards and even will disobey rules or laws that violate these principles. Internal values become more important than the expectations of significant others. An example of the postconventional or principled approach comes from World War II. When the USS Indianapolis sank after being torpedoed, one Navy pilot disobeyed orders and risked his life to save men who were being picked off by sharks. The pilot was operating from the highest level of moral development in attempting the rescue despite a direct order from superiors.

When managers operate from this highest level of development, they use transformative or servant leadership, focusing on the needs of followers and encouraging others to think for themselves and to engage in higher levels of moral reasoning. Employees are empowered and given opportunities for constructive participation in governance of the organization.

The great majority of managers operate at level two, the conventional level. A few have not advanced beyond level one. Only about 20 percent of American adults reach the level- three stage of moral development. People at level three are able to act in an independent, ethical manner regardless of expectations from others inside or outside the organization. Managers at level three of moral development will make ethical decisions whatever the organizational consequences for them.

One interesting study indicates that most researchers fail to account for the different ways in which women view social reality and develop psychologically and have thus consistently classified women as being stuck at lower levels of development. Researcher Carol Gilligan suggested that the moral domain be enlarged to include responsibility and care in relationships. Women may, in general, perceive moral complexities more astutely than men and make moral decisions based not on a set of absolute rights and wrongs but on principles of not causing harm to others.23

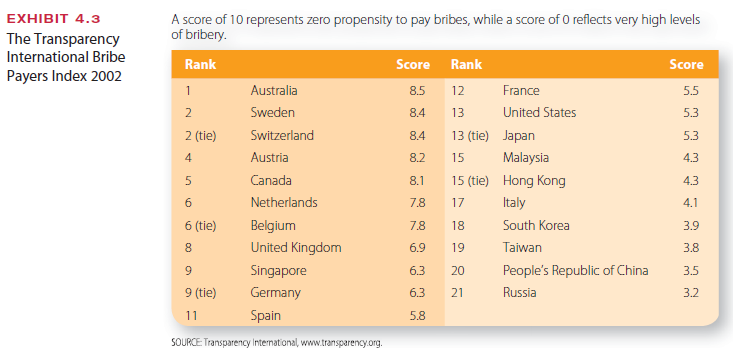

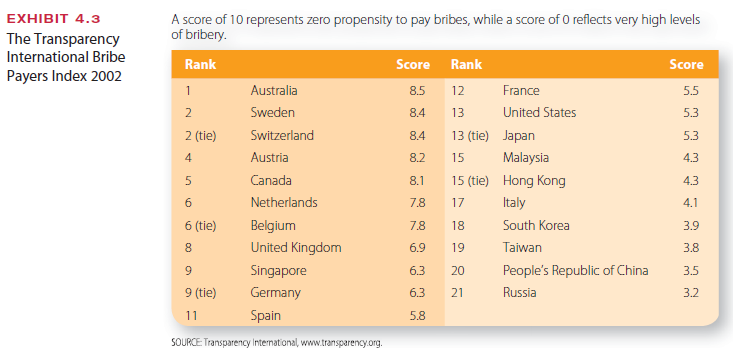

Globalization makes ethical issues even more complicated for today’s managers.24 For ex- ample, although tolerance for bribery is waning, bribes are still considered a normal part of doing business in many foreign countries. Transparency International, an international orga- nization that monitors corruption, publishes an annual report ranking countries according to how many bribes are offered by their international businesses. Exhibit 4.3 shows results of the organization’s most recent available report. International businesses based in countries such as Russia, China, Taiwan, and South Korea were found to be using bribes “on an exceptional and intolerable scale.” Multinational firms in the United States, Japan, France, and Spain, however, also revealed a relatively high propensity to pay bribes overseas.25

American managers working in foreign countries require sensitivity and an openness to other systems, as well as the fortitude to resolve these difficult issues. Companies that don’t oil the wheels of contract negotiations in foreign countries can put themselves at a compet- itive disadvantage, yet managers walk a fine line when making deals overseas. Although U.S. laws allow certain types of payments, tough federal antibribery laws also are in place. Goldman Sachs got preapproval from the U.S. Justice Department and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) before agreeing to pay a $67 million fee to Beijing power brokers to facilitate a joint venture in China.26 But many other companies, including Monsanto, ScheringPlough, and IBM, have gotten into trouble with the SEC for using incentives to facilitate foreign deals.

2. THE ORGANIZATION

Rarely can ethical or unethical corporate actions be attributed solely to the personal values of a single manager. The values adopted within the organization are important, especially when we understand that most people are at the level-two stage of moral development, which means they believe their duty is to fulfill obligations and expectations of others.

Consider, for example, how David Myers slid into trouble at WorldCom, which disinte- grated in an $11 billion fraud scandal.27

Research verifies that these values strongly influence employee actions and decision making.28 In particular, corporate culture, as described in Chapter 3, lets employees know what beliefs and behaviors the company supports and those it will not tolerate.

If unethical behavior is tolerated or even encouraged, it becomes routine. In many com- panies, employees believe that if they do not go along, their jobs will be in jeopardy or they will not fit in.29

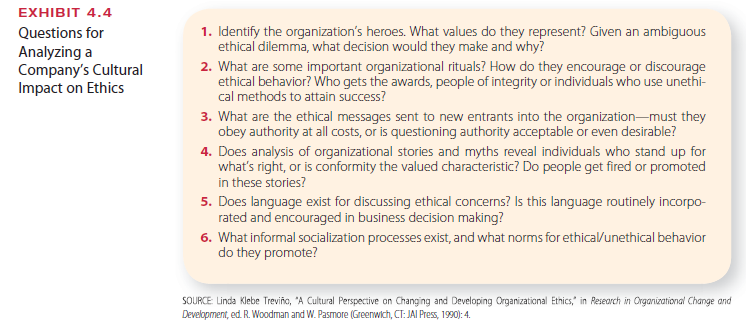

Culture can be examined to see the kinds of ethical signals transmitted to employees. Exhibit 4.4 lists questions to ask to understand the cultural system. High ethical standards can be affirmed and communicated through public awards and ceremonies. Heroes provide role models that can either support or refute ethical decision making. Culture is not the only aspect of an organization that influences ethics, but it is a major force because it de- fines company values. Other aspects of the organization, such as explicit rules and policies, the reward system, the extent to which the company cares for its people, the selection sys- tem, emphasis on legal and professional standards, and leadership and decision processes, also can affect ethical values and manager decision making.

Source: Daft Richard L., Marcic Dorothy (2009), Understanding Management, South-Western College Pub; 8th edition.

I’ve recently started a web site, the info you offer on this website has helped me greatly. Thank you for all of your time & work. “‘Tis our true policy to steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world.” by George Washington.