1. The Nature of Leadership

No topic is probably more important to organizational success today than leadership. Leadership matters. In most situations, a team, military unit, or volunteer organization is only as good as its leader. Consider the situation in Iraq, as U.S. military advisors strive to build Iraqi forces that can take over security duties without support from coalition troops. Many trainers say they encounter excellent individual soldiers and junior leaders but that many of the senior commanders are stuck in old authoritarian patterns that undermine their units. Whether an Iraqi unit succeeds or fails often comes down to one person—its commander—so advisors are putting emphasis on finding and strengthening good leaders.2

Top leaders make a difference in business organizations as well. Baron Partners Fund, which picks stocks based largely on an evaluation of companies’ senior executives, was the best-performing diversified stock fund of 2004, with a return of 42 percent. Manager Ron Baron says top leaders who are smart, honorable, and treat their employees right typically lead their companies to greater financial success and greater shareholder returns.3

The concept of leadership continues to evolve as the needs of organizations change. Among all the ideas and writings about leadership, three aspects stand out—people, influence, and goals. Leadership occurs among people, involves the use of influence, and is used to attain goals.4 Influence means that the relationship among people is not passive. Moreover, influence is designed to achieve some end or goal. Thus, leadership as defined here is the ability to influence people toward the attainment of goals. This definition captures the idea that leaders are involved with other people in the achieve- ment of goals.

Leadership is reciprocal, occurring among people.5 Leadership is a “people” activity, dis- tinct from administrative paper shuffling or problem-solving activities. Leadership is dynamic and involves the use of power to influence people and get things done. Role models for leadership can come from wide and varied sources, as shown in the Spotlight on Skills.

2. Leadership for Contemporary Times

The environmental context in which leadership is practiced influences which approach might be most effective, as well as what kinds of leaders are most admired by society. The technology, economic conditions, labor conditions, and social and cultural mores of the times all play a role. A significant influence on leadership styles in recent years is the turbu- lence and uncertainty of the environment in which most organizations are operating. Ethi- cal and economic difficulties, corporate governance concerns, globalization, changes in technology, new ways of working, shifting employee expectations, and significant social transitions have contributed to a shift in how we think about and practice leadership.

Of particular interest for leadership in contemporary times is a post-heroic approach that focuses on the subtle, unseen, and often unrewarded acts that good leaders perform every day, rather than on the grand accomplishments of celebrated business heroes.6 During the 1980s and 1990s, leadership became equated with larger-than-life personalities, strong egos, and personal ambitions. In contrast, the post-heroic leader’s major characteristic is humility.7 Humility means being unpretentious and modest rather than arrogant and prideful. Humble leaders don’t have to be in the center of things. They quietly build strong, enduring companies by developing and supporting others rather than touting their own abilities and accomplishments. Two approaches that are in tune with post-heroic leader- ship for today’s times are Level 5 leadership and interactive leadership, a style that is com- monly used by women leaders.

2.1. LEVEL 5 LEADERSHIP

A recent five-year study conducted by Jim Collins and his research associates identified the critical importance of what Collins calls Level 5 leadership in transforming companies from merely good to truly great organizations.8 As described in his book Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap . . . and Others Don’t, Level 5 leadership refers to the highest level in a hierarchy of manager capabilities, as illustrated in Exhibit 11.1. A key characteristic of Level 5 leaders is an almost complete lack of ego, coupled with a fierce resolve to do what is best for the organization. In contrast to the view of great leaders as larger-than-life personalities with strong egos and big ambitions, Level 5 leaders often seem shy and unpretentious. Although they accept full responsibility for mistakes, poor results, or failures, Level 5 leaders give credit for successes to other people. For example, Joseph F. Cullman III, former CEO of Philip Morris, staunchly refused to accept credit for the company’s long-term success, citing his great colleagues, successors, and predecessors as the reason for the accomplishments. Another example is Darwin E. Smith. When he was promoted to CEO of Kimberly-Clark, Smith questioned whether the board really wanted to appoint him because he didn’t believe he had the qualifications a CEO needed.

Despite their personal humility, Level 5 leaders have a strong will to do whatever it takes to produce great and lasting results for their organizations. They are extremely ambitious for their companies rather than for themselves. This goal becomes highly evident in the area of succession planning. Level 5 leaders develop a solid corps of leaders through- out the organization, so that when they leave the company, it can continue to thrive and grow even stronger. Egocentric leaders, by contrast, often set their successors up for failure because it will be a testament to their own greatness if the company doesn’t perform well without them. Rather than an organization built around “a genius with a thousand help- ers,” Level 5 leaders build an organization with many strong leaders who can step forward and continue the company’s success. These leaders want everyone in the organization to develop to their fullest potential.

2.2. WOMEN’S WAYS OF LEADING

The focus on minimizing personal ambition and developing others is also a hallmark of interactive leadership, which has been found to be common among female leaders. Research indicates that women’s style of leadership is typically different from most men’s and is particularly suited to today’s organizations.9 Using data from actual performance evalua- tions, one study found that when rated by peers, subordinates, and bosses, female managers score significantly higher than men on abilities such as motivating others, fostering com- munication, and listening.10

Interactive leadership means that the leader favors a consensual and collaborative process, and influence derives from relationships rather than position power and formal authority.11 For example, Nancy Hawthorne, former chief financial officer at Continental Cablevision Inc., felt that her role as a leader was to delegate tasks and authority to others and to help them be more effective. “I was being traffic cop and coach and facilitator,” Hawthorne says. “I was always into building a department that hummed.”12 Similarly, Terri Kelly, who took over as CEO of W. L. Gore in 2005, says her goal is to provide overall direction and guidance, not to micromanage and tell people how to do their jobs.13 It is important to note that men can be interactive leaders as well, as demonstrated by the example of Pat McGovern of International Data Group earlier in the chapter. For McGovern, having personal contact with employees and letting them know they’re appre- ciated is a primary responsibility of leaders. The characteristics associated with interactive leadership are emerging as valuable qualities for both male and female leaders in today’s workplace. Values associated with interactive leadership include personal humility, inclusion, relationship building, and caring.

3. Leadership Versus Management

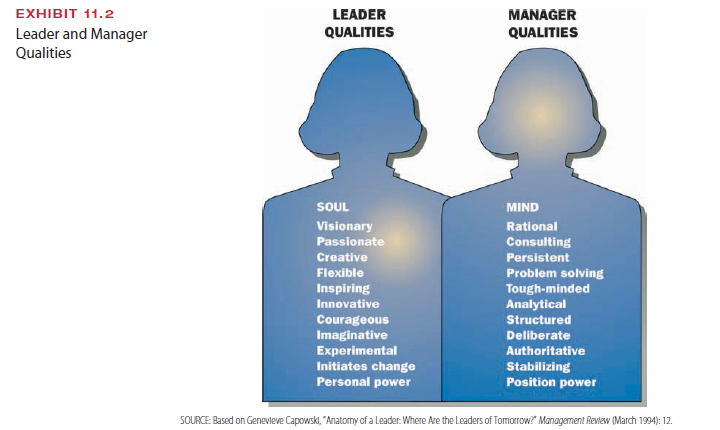

Much has been written in recent years about the leadership role of managers. Management and leadership are both important to organizations. Effective managers have to be leaders, too, because distinctive qualities are associated with management and leadership that provide dif- ferent strengths for the organization, as illustrated in Exhibit 11.2. As shown in the exhibit, management and leadership reflect two different sets of qualities and skills that frequently overlap within a single individual. A person might have more of one set of qualities than the other, but ideally a manager develops a balance of both manager and leader qualities.

A primary distinction between management and leadership is that management promotes stability, order, and problem solving within the existing organizational structure and systems. Leadership promotes vision, creativity, and change. In other words, “a manager takes care of where you are; a leader takes you to a new place.”14 Leadership means questioning the status quo so that outdated, unproductive, or socially irresponsible norms can be replaced to meet new challenges.

4. Leadership Traits

Early efforts to understand leadership success focused on the leader’s personal characteristics or traits. Traits are the distinguishing per- sonal characteristics of a leader, such as intelligence, values, self- confidence, and appearance. The early research focused on leaders who had achieved a level of greatness, and hence was referred to as the Great Man approach. The idea was relatively simple: Find out what made these people great, and select future leaders who already exhibited the same traits or could be trained to develop them. Generally, early research found only a weak relationship between personal traits and leader success.15

In recent years, interest in examining leadership traits has reemerged. In addition to personality traits, physical, social, and work-related char- acteristics of leaders have been studied.16 Exhibit 11.3 summarizes the physical, social, and personal leadership characteristics that have received the greatest research support. However, these characteristics do not stand alone. The appropriateness of a trait or set of traits depends on the leadership situation. The same traits do not apply to every organization or situation. Further studies expand the understanding of leadership beyond the personal traits of the individual to focus on the dynamics of the relationship between leaders and followers.

Source: Daft Richard L., Marcic Dorothy (2009), Understanding Management, South-Western College Pub; 8th edition.

I have learn some just right stuff here. Certainly worth bookmarking for revisiting. I surprise how much effort you set to make this kind of magnificent informative site.