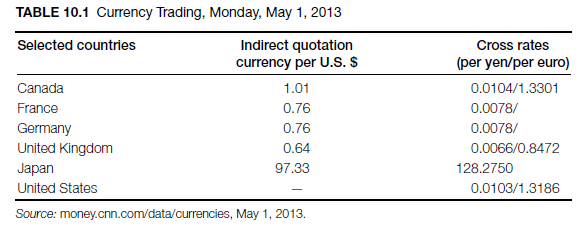

An exchange rate is the number of units of a given currency that can be purchased for one unit of another currency. It is a common practice in world currency markets to use the indirect quotation, which is quoting all exchange rates (except for the British pound) per U.S. dollar. The Financial Times foreign exchange data for May 1, 2013, for example, shows the quotation for the Canadian dollar as being 1.01 per one U.S. dollar. Direct quotation is the expression of the number of U.S. dollars required to buy one unit of foreign currency (Table 10.1). The direct U.S. dollar quotation on May 1, 2013, for the Canadian dollar was U.S. $0.99. Although it is common for foreign currency markets around the world to quote rates in U.S. dollars, some traders state the price of other currencies in terms of the dealer’s home currency (cross rates), for example, Swiss francs against Japanese yen, Hong Kong dollar against Colombian pesos, and so on.

Strictly speaking, it is reasonable to state that the rate of the foreign currency against the dollar is a cross rate to dealers in third countries.

The foreign exchange market is a place where foreign currency is purchased and sold. In the same way that the relationship between goods and money in ordinary business transactions is expressed by the price, so the relationship of one currency to another is expressed by the exchange rate. A large proportion of the foreign exchange transactions undertaken each day are between banks in different countries. These transactions are often a result of the wishes of the banks’ customers to consummate commercial transactions, that is, payments for imports or receipts for exports. Other reasons for individual companies or governments to enter into the foreign exchange market as buyers or sellers of foreign currencies include the following:

- Individuals and companies use foreign currencies for foreign travel, purchase of foreign stocks and bonds, and foreign investment; foreign currencies are also used in receipt of income (e.g., interest, dividends, royalties) from abroad and payment of such income in foreign currency.

- Central banks enter the foreign exchange market and buy or sell foreign currency (in exchange for domestic currency) to stabilize the national currency, that is, to reduce violent fluctuations in exchange rates without destroying the viability and freedom of the foreign exchange market.

- Individuals and companies speculate in foreign currency, that is, they purchase foreign currency at a low rate with the hope that they can sell it at a profit.

Foreign exchange trading is not limited to one specific location. It takes place wherever such deals are made, for example, in a private office or even at home, far away from the dealing rooms or facilities of companies. Most of these transactions are carried out between commercial banks and their customers or between commercial banks, which buy and sell foreign currencies in response to the needs of their clients. For example, a Canadian bank sells Canadian dollars to a French bank in exchange for euros. This transaction, in effect, allows the Canadian bank the right to draw a check on the French bank for the amount of the deposit denominated in euros. Similarly, it will enable the French bank to draw a check in Canadian dollars for the amount of the deposit

Foreign exchange rates are based on the supply and demand for various currencies, which, in turn, are derivatives of the fundamental economic factors and technical conditions in the market (Salvatore, 2005). In the United States, for example, the continuous deterioration in the trade deficit in the 1970s, mainly due to increased consumption expenditures on foreign goods, led to an oversupply of dollars in foreign central banks. This, in turn, resulted in a lower dollar in foreign exchange markets. Besides a country’s balance of payments position, factors such as interest rates, growth in the money supply, inflation, and confidence in the government are important determinants of supply and demand for foreign currencies and, thus, the exchange rate. The following are some examples:

- The U.S. dollar depreciated substantially against the euro and other major currencies in recent years partly due to interest rate tightening by the European Central Bank and high U.S. trade and budget deficits. Between April 2012 and February 2013, for example, the dollar exchange rate declined from 1 euro = 1.32 USD to 1 euro = 1.36 USD. Currency traders buy currencies of countries with high interest rates in order to maximize their investment returns and sell those currencies with low interest rates.

- The Mexican peso has been appreciating during the past few years due to an increase in the inflow of funds resulting from the rise of international oil prices. The increase of foreign investment in the country has also contributed to the rise in value of the peso, thus causing a reduction in its current account deficit and foreign debt.

- The Japanese yen has depreciated by a substantial margin against other currencies since April 2013 due to the government’s aggressive policy of monetary easing.

- The Chinese renminbi has appreciated against major currencies such as the British pound and the U.S. dollar.

Exchange rate fluctuations can have a profound effect on international trade. Export- import firms are vulnerable to foreign exchange risks whenever they enter into an obligation to accept or deliver a specified amount of foreign currency at a future point in time. These firms are then faced with the prospect that future changes in foreign currency values could either reduce the amount of their receipts or increase their payments in foreign currency. U.S. importers of Japanese goods, for example, are likely to incur significant losses when the dollar takes a fall against the yen, often wiping out a significant portion of their profits. In some cases, it may also be that such changes will bring about financial benefits.

The most important types of transactions that contribute to foreign exchange risks in international trade include the following:

- Purchase of goods and services whose prices are stated in foreign currency, that is, payables in foreign currency

- Sales of goods and services whose prices are stated in foreign currency, that is, receivables in foreign currency

- Debt payments to be made or accepted in foreign currency.

Most export-import companies do not have the expertise to handle such unanticipated changes in exchange rates. Banks with international trade capabilities and consultants can help assess currency risks and advise companies to take appropriate measures.

The impact of exchange rate fluctuations on export trade can be illustrated by the following example. Since the dollar began to decline against major currencies, many European and Asian exporters to the U.S. market have been faced with the difficult task of balancing the need to increase prices to preserve profit margins and the importance of keeping prices stable to maintain market shares. Many exporters have been reluctant to increase the prices of their exports to fully offset the decline in the dollar. Some have responded by shifting factories to North America in order to cushion them from currency fluctuations. Prominent examples include the establishment of production facilities by DaimlerChrysler in Alabama and BMW in South Carolina. In April, 2013, General Motors blamed the strength of the Australian dollar, which in April 2013 hit a twenty-eight-year high on trade-weighted basis, for a decision to cut five hundred jobs in Australia. Businesses blame the rising dollar for undermining exports and inward investment. In May 2013, South Korea’s government announced $10 billion in new financial support to help the country’s exporters, as April data showed a monthly fall in exports amid slowing global demand and a weaker Japanese currency.

The impact of exchange rate risks is felt more by export-import companies than by domestic firms. To the extent that an exporter’s inputs are domestic, a strong domestic currency could lead to loss of domestic and foreign markets. Importers also face a loss of domestic markets due to the rise in the price of imports if the domestic currency weakens. In addition, such firms are vulnerable to exchange risks arising from receivables or payables in foreign currency.

Source: Seyoum Belay (2014), Export-import theory, practices, and procedures, Routledge; 3rd edition.

13 Jul 2021

14 Jul 2021

13 Jul 2021

15 Jul 2021

14 Jul 2021

14 Jul 2021