There are several ways in which export-import companies can protect themselves against unanticipated changes in exchange rates. The risk associated with such transactions is that the exchange rate might change between the date the export contract was made and the date of payment (the settlement date), which is often sixty to ninety days after contract or shipment of the merchandise.

1. Shifting the Risk to Third Parties

1.1. Hedging in Financial Markets

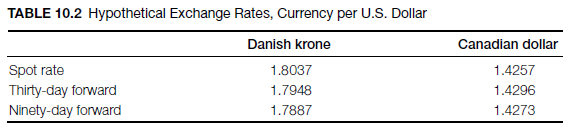

Through various hedging instruments, firms can reduce the adverse impact of foreign currency fluctuations. This allows firms to lock in the exchange rate today for receipts or payments in foreign currency that will happen at some time in the future. Current foreign exchange rates are called spot prices; those occurring at some time in the future are referred to as forward prices. If the currency in question is more expensive for forward delivery (for delivery at some future date) than for ordinary spot delivery (i.e., for delivery two business days following the agreed-upon exchange date), it is said to be at a premium. If it is less expensive for forward delivery than for spot delivery, it is said to be at a discount.

In Table 10.2, the forward krone is at a premium since the forward krone is more expensive than the spot. The forward Canadian dollar is at a discount because its forward price is cheaper than spot. When viewed from the point of view of the U.S. dollar, it can also be stated that the forward dollar is at a discount in relation to the krone or that the forward U.S. dollar is at a premium in relation to the Canadian dollar.

It is pertinent to underscore some salient points about hedging in foreign exchange markets:

- Hedging is not always the most appropriate technique to limit foreign exchange risks. There are fees associated with hedging, and such costs reduce the expected value from a given transaction. Export-import firms should seriously consider hedging when a high proportion of their cash flow is vulnerable to exchange rate fluctuations. This means that firms should determine the acceptable level of risk that they are willing to take. In contrast, firms with a small portion of their total cash exposed to foreign exchange rate movements may be better off playing the law of averages—shortfalls could be eventually offset by windfall gains.

- Hedging does not protect long-term cash flows. Hedging does not insulate firms from long-term adjustments in currency values. (O’Connor and Bueso, 1990). Thus, it should not be used to cover anticipated changes in currency values. A U.S. importer of German goods would have found it difficult to adequately hedge against the predictable fall of the dollar during the period 2007-2009. The impact of such action is felt in terms of higher dollar prices paid for imports.

- Forward market hedges are available in a very limited number of currencies. Most currencies are not traded in the forward market. However, many countries peg their currency to that of a major industrial country whose currency is traded in the forward market. Many Latin American countries, for example, peg their currencies to the U.S. dollar. This insulates U.S. firms from foreign exchange risk in these countries unless the country changes from the designated (pegged) official rate. Foreign firms, that is, non-U.S. firms, in these countries can reduce potential risks by buying or selling dollars (in the event of purchases or sales to these countries) forward as the case may be.

Example 1: Suppose the Colombian peso is pegged to the U.S. dollar at $1 = 1,000 pesos. A British firm that is to make payment in pesos for its imports from Colombia could hedge its position by buying U.S. dollars forward. On the settlement date, pounds will be converted into dollars, which, in turn, could be converted into pesos. This assumes that Colombia does not change the pegged rate during the period.

- Hedging should not be used for individual transactions. Since most export-import firms engage in transactions that result in inflows and outflows of foreign currencies, the most appropriate strategy to reduce transaction costs is to hedge the exported net receivable or payable in foreign currency.

Example 2: Suppose a Canadian firm has receivables from two Japanese buyers amounting to five million yen and payables to four Japanese suppliers worth nine million yen. Instead of hedging all six transactions, the Canadian firm should cover only the net short position (i.e., four million yen) in yen. This reduces the transaction cost of exchanging currencies for the firm.

1.2. Spot and Forward Market Hedge

As previously noted, a spot transaction is one in which foreign currencies are purchased and sold for immediate delivery, that is, within two business days following the agreed-upon exchange date. The two-day period is intended to allow the respective commercial banks to make the necessary transfer. A forward transaction is a contract that provides for two parties to exchange currencies on a future date at an agreed-upon exchange rate. The forward rate is usually quoted for one month, three months, four months, six months, or one year. Unlike hedging in the spot market, forward market hedging does not require borrowing or tying up a certain amount of money for a period of time. This is because the firm agrees to buy or sell the agreed amount of currency at a determinable future date, and actual delivery does not take place before the stipulated date.

Example 1: Spot market hedge. On September 1, a U.S. importer contracts to buy German machines for a total cost of 600,000 euros. The payment date is December 1. When the contract is signed on September 1, the spot exchange rate is $0.5000 per euro and the December forward rate is $0.5085 per euro. The U.S. importer believes that the euro is going to appreciate in value in relation to the dollar.

The import firm could buy 600,000 euros on the spot market on September 1 for $300,000 and deposit the euros in an interest-bearing account until the payment date. If the firm does not hedge and the spot exchange rate rises to $0.5128 euro on December 1, the importer will suffer a loss of $7,680, or (0.5128-0.5000) x 600,000.

The import firm could also borrow $300,000 and convert at the spot rate for 600,000 euros. The euros could be lent out or put in certificates of deposit or some other investment vehicle until December 1, when payment is to be made to the exporter. The U.S. dollar loan will be paid from the proceeds of the resale without any foreign exchange exposure. This is often referred to as credit hedge.

Example 2: Forward market hedge. On September 1, a U.S. exporter contracts to sell U.S. goods for SF (Swiss francs) 250,000. The goods are to be delivered and payment received on December 1. When the contract is signed, the spot exchange rate is $0.6098/SF and the December forward rate is $0.6212/SF. The Swiss franc is expected to depreciate, and the December 1 spot exchange rate is likely to fall to $0.5696/SF.

The U.S. exporter has two options. First, it can sell its franc receivable forward now and receive $0.6212 per franc on the settlement date (December). Second, it can wait until December and then sell francs on spot. Clearly, the forward market hedge is preferable, and the U.S. exporter would gain: (0.6212-0.6098) x 250,000 = $2,850. The decision to use the forward market is based upon an assessment of what the future spot rate is likely to be. It is also important to bear in mind the impact of transaction costs before a firm makes a decision on what action to take. A credit hedge could have been feasible if the spot rate in United States had been higher than the forward rate.

1.3. Swaps

A swap transaction is a simultaneous purchase and sale of a certain amount of foreign currency for two different value dates. The central feature of this transaction is that the bank arranges the swap as a single transaction, usually between two partners. Swaps are used to move out of one currency and into another for a limited period of time without the exchange risk of an open position.

Example: A U.S. firm sells semiconductor chips to Nippon, a Japanese firm, for sixty million yen, and payment was made upon receipt of shipment on October 1. The U.S. firm has payables to Nippon and other Japanese firms of about sixty million yen for the purchase of merchandise, with payment due on January 1. The spot exchange rate on October 1 is 120 yen per dollar and the January sixty- day forward rate is 125 yen per dollar.

The U.S. firm sells its sixty-million-yen receipts on the spot market for $500,000 at the price of $1 = 120 yen. Simultaneously, the firm contracts with the same or different bank to purchase sixty million yen in sixty days at the forward price of 125 yen per dollar. In addition to its normal profits on its exports, the U.S. firm has made a profit of 2.5 million yen from its swap transaction. In cases in which the delivery date to the Japanese firms is not certain, the U.S. firm could use a time option that leaves the delivery date open, while locking the exchange rate at a specified rate.

1.4. Other Hedging Techniques

Export/import companies can use different techniques in order to avoid foreign exchange risk:

- Hedging receipts against payables: An export firm that has receivables in foreign currency (thirty million British pounds) could hedge its receipts against a payable of thirty million pounds to the same or another firm at about the same time. This is achieved with no additional cost and without going through the foreign exchange market. The same method could be used between export-import firms and their branches or other affiliate companies abroad.

- Accelerating or delaying payments: If an importer reasonably believes that its domestic currency is likely to depreciate in terms of the currency of its foreign supplier, it will be motivated to accelerate its payments. This could be achieved by buying the requisite foreign currency before it appreciates in value. However, payments could be delayed if the buyer believes that the foreign currency in which payment is to be made is likely to depreciate in value in terms of the domestic currency.

1.5. Guarantees and Insurance Coverage

In certain cases, exporters require a guarantee by the importer, a bank, or another agency against the risk of devaluation or exchange controls. Certain types of insurance coverage are also available against exchange controls. In view of its high cost, hedging is a better alternative than insurance.

2. Shifting the Risk to the Other Party

2.1. Invoicing in One’s Own Currency

Risks accompany all transactions involving a future remittance or payment in foreign currency. If the payment or receipt for a transaction is in one’s own currency, the risk arising from currency fluctuations is shifted to the other party. Suppose a Korean firm negotiated to make payments (ninety days after the contract date) in its domestic currency (won) for its imports of equipment from a Canadian manufacturer. This shifts the foreign currency risk to the exporter, which will have to convert its won receipts into Canadian dollars. Payment in one’s own currency shifts not only the risk of devaluation to the other party but also the risk of imposition of exchange controls by the importing country against convertibility and repatriation of foreign currency.

2.2. Invoicing in Foreign Currency

In the event that the agreement stipulates that payment is to be made in foreign currency, it is important for the exporter to require inclusion of a provision that protects the value of its receipts from currency devaluation. In the previous example, the contract could provide for an increase in payment to compensate the Canadian manufacturer/exporter for losses arising from currency fluctuations.

Another method would be to make certain assumptions about possible adverse changes in the exchange rate and add it to the price. If currency changes are likely to result in a 10 percent loss, the price change could be increased by that percentage. An export contract could also provide for the establishment of an escrow account in a third country’s currency (a stable currency) from which payments will be made. This protects the exporter from losses due to depreciation of the importer’s currency.

Source: Seyoum Belay (2014), Export-import theory, practices, and procedures, Routledge; 3rd edition.

WONDERFUL Post.thanks for share..more wait .. …