Every business entity has a unique organizational culture that impacts strategic-planning activities. Organizational culture is “a pattern of behavior that has been developed by an organization as it learns to cope with its problem of external adaptation and internal integration, and that has worked well enough to be considered valid and to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel.”4 This definition emphasizes the importance of matching external with internal factors in making strategic decisions. Organizational culture captures the subtle, elusive, and largely unconscious forces that shape a workplace. Remarkably resistant to change, culture can represent a major strength or weakness for any firm. It can be an underlying reason for strengths or weaknesses in any of the major business functions.

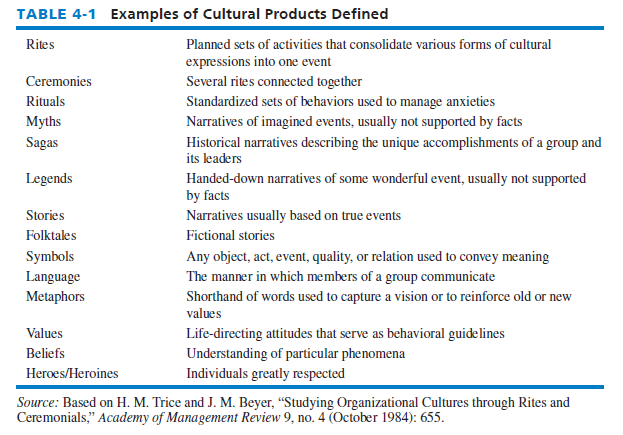

Defined in Table 4-1, cultural products include values, beliefs, rites, rituals, ceremonies, myths, stories, legends, sagas, language, metaphors, symbols, folktales, and heroes and heroines. These products or dimensions are levers that strategists can use to influence and direct strategy formulation, implementation, and evaluation activities. An organization’s culture compares to an individual’s personality in the sense that no two organizations have the same culture and no two individuals have the same personality. Both culture and personality are enduring and can be warm, aggressive, friendly, open, innovative, conservative, liberal, harsh, or likable.

At Google and Facebook, for example, the cultures are informal. Google employees are encouraged to wander the halls on employee-sponsored scooters and brainstorm on public whiteboards provided everywhere. In contrast, the culture at Procter & Gamble (P&G) is so rigid that employees jokingly call themselves “Proctoids.” Despite this difference, the two companies are swapping employees and participating in each other’s staff training sessions. Why? One reason is that P&G spends more money on advertising than any other company and Google desires more of P&G’s roughly $8 billion in annual advertising expenses.

Dimensions of organizational culture permeate all the functional areas of business. It is something of an art to uncover the basic values and beliefs that are deeply buried in an organization’s rich collection of stories, language, heroes, and rituals, but cultural products can represent both important strengths and weaknesses. Culture is an aspect of an organization that can no longer be taken for granted in performing an internal strategic-management audit, because culture and strategy must work together.

The strategic-management process takes place largely within a particular organization’s culture. Lorsch found that executives in successful companies are emotionally committed to the firm’s culture, but he concluded that culture can inhibit strategic management in two basic ways. First, managers frequently miss the significance of changing external conditions because they are blinded by strongly held beliefs. Second, when a particular culture has been effective in the past, the natural response is to stick with it in the future, even during times of major strategic change.5 An organization’s culture must support the collective commitment of its people to a common purpose. It must foster competence and enthusiasm among managers and employees.

Organizational culture significantly affects business decisions and must therefore be evaluated during an internal strategic-management audit. If strategies can capitalize on cultural strengths, such as a strong work ethic or highly ethical beliefs, then management often can swiftly and easily implement changes. However, if the firm’s culture is not supportive, strategic changes may be ineffective or even counterproductive. A firm’s culture can become antagonistic to new strategies, with the result being confusion and disorientation.

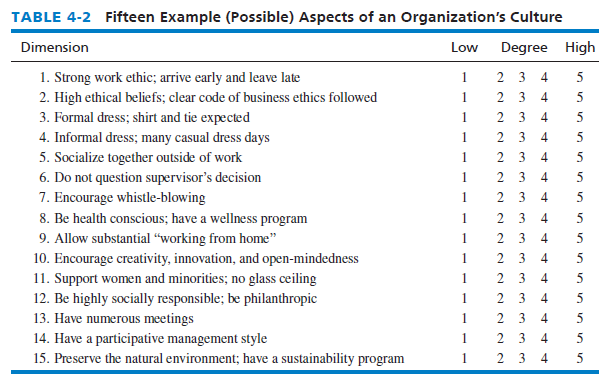

Table 4-2 provides some example (possible) aspects of an organization’s culture. Note that you might want to ask employees and managers to rate the degree that the dimension characterizes the firm. When one firm acquires another firm, integrating the two cultures effectively can be vital for success. For example, in Table 4-2, one firm may score mostly 1s (low) and the other firm may score mostly 5s (high), which would present a challenging strategic problem.

An organization’s culture should infuse individuals with enthusiasm for implementing strategies. Allarie and Firsirotu emphasized the need to understand culture:

Culture provides an explanation for the insuperable difficulties a firm encounters when it attempts to shift its strategic direction. Not only has the “right” culture become the essence and foundation of corporate excellence, it is also claimed that success or failure of reforms hinges on management’s sagacity and ability to change the firm’s driving culture in time and in time with required changes in strategies.6

Internal strengths and weaknesses associated with a firm’s culture sometimes are overlooked because of the interfunctional nature of this phenomenon. This is a key reason why strategists need to view and understand their firm as a sociocultural system. Success is oftentimes determined by linkages between a firm’s culture and strategies. The challenge of strategic management today is to bring about the changes in organizational culture and individual mind-sets that are needed to support the formulation, implementation, and evaluation of strategies.

Source: David Fred, David Forest (2016), Strategic Management: A Competitive Advantage Approach, Concepts and Cases, Pearson (16th Edition).

I?¦m no longer sure where you are getting your info, but good topic. I needs to spend a while finding out much more or understanding more. Thanks for excellent information I used to be in search of this information for my mission.