1. Introduction to entrepreneurship

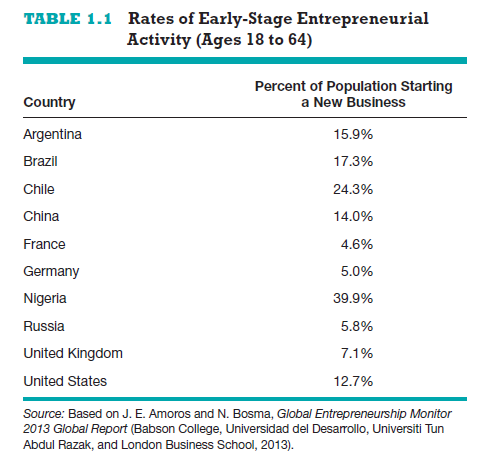

There is tremendous interest in entrepreneurship around the world. Although this statement may seem bold, there is evidence supporting it, some of which is provided by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM). GEM, which is a joint research effort by Babson College, London Business School, Universidad del Desarrollo (Santiago, Chile), and Universiti Tun Abdul Razak (Malaysia), tracks entrepreneurship in 70 countries, including the United States. Of par- ticular interest to GEM is early stage entrepreneurial activity, which consists of businesses that are just being started and businesses that have been in ex- istence for less than three and a half years. A sample of the rate of early-stage entrepreneurial activity in countries included in the GEM study is shown in Table 1.1. While the highest rates of entrepreneurial start-up activities occur in low-income countries, where good jobs are not plentiful, the rates are also impressive in high-income countries such as Germany (5.0 percent), United Kingdom (7.1 percent), and the United States (12.7 percent). What the 12.7 percent means for the United States is that almost 1 out of every 8 American adults is actively engaged in starting a business or is the owner/manager of a business that is less than three-and-a-half-years old.2

The GEM study also identifies whether its respondents are starting a new business to take advantage of an attractive opportunity or because of necessity to earn an income. The majority of people in high-income countries are drawn to entrepreneurship to take advantage of attractive opportunities. The reverse is true of people in low-income countries, who tend to be drawn to entrepreneur- ship primarily because of necessity (resulting from a lack of career prospects).3

One criticism of entrepreneurship, which is often repeated in the press, is that the majority of new businesses fail. It simply isn’t true. The often used statis- tic that 9 out of 10 businesses fail in their first few years is an exaggeration. For example, evidence indicates that the three-year survival rates for entrepreneurial ventures established in Denmark is 53.5 percent, while it is up to 66.9 percent in other parts of Europe.4 Historically, survival rates of entrepreneurial firms launched in the United States have been as high as 50 percent after four years. While overall these figures are heartening, the percentage of firms that do fail in Europe, the United States, and throughout the world shows that a motivation to start and run a business isn’t enough; it must be coupled with a solid business idea, good financial management, and effective execution to maximize chances for success. In this book, we’ll discuss many examples of entrepreneurial firms and the factors separating successful new ventures from unsuccessful ones.

Many people see entrepreneurship as an attractive career path. Think about your friends and others you know. In all probability, you are acquainted with at least one or two people who want to become an entrepreneur—either now or at some point in the future. The number of books dealing with starting one’s own business is another indication entrepreneurship is growing in popularity. Amazon.com, for example, currently lists over 36,900 books and other items dealing with entrepreneurship and over 89,900 books concerned with small businesses. The number of books on small business is up from 62,700 just three years ago.

2. What is entrepreneurship and Why is it important?

The word entrepreneur derives from the French words entre, meaning “between,” and prendre, meaning “to take.” The word was originally used to describe people who “take on the risk” between buyers and sellers or who “undertake” a task such as starting a new venture.5 Inventors and entrepreneurs differ from each other. An inventor creates something new. An entrepreneur assembles and then integrates all the resources needed—the money, the people, the business model, the strategy, and the risk-bearing ability—to transform the invention into a viable business.6

Entrepreneurship is defined as the process by which individuals pursue opportunities without regard to resources they currently control for the pur- pose of exploiting future goods and services.7 Others, such as venture capitalist Fred Wilson, define it more simply, seeing entrepreneurship as the art of turn- ing an idea into a business. In essence, an entrepreneur’s behavior finds him or her trying to identify opportunities and putting useful ideas into practice.8 The tasks called for by this behavior can be accomplished by either an individual or a group and typically require creativity, drive, and a willingness to take risks. Zach Schau, the cofounder of Pure Fix Cycles, exemplifies all these qualities. Zach saw an opportunity to create a new type of bicycle and a new type of bi- cycling experience for riders, he risked his career by passing up alternatives to work on Pure Fix Cycles full time, and he’s now working hard to put Pure Fix Cycles in a position to deliver a creative and useful product to its customers.

In this book, we focus on entrepreneurship in the context of an entrepre- neur or team of entrepreneurs launching a new business. However, ongoing firms can also behave entrepreneurially. Typically, established firms with an entrepreneurial emphasis are proactive, innovative, and risk-taking. For ex- ample, Google is widely recognized as a firm in which entrepreneurial behaviors are clearly evident. Larry Page, one of Google’s cofounders, is at the heart of Google’s entrepreneurial culture. With his ability to persuade and motivate oth- ers’ imaginations, Page continues to inspire Google’s employees as they develop innovative product after innovative product. To consider the penetration Google has with some of its innovations, think of how often you and people you know use the Google search engine, Gmail, Google Maps, or Google Earth. Google is currently working on a bevy of far-reaching innovations, such as Google Glasses and self-driving cars. Similarly, studying Facebook or Dropbox’s ability to grow and succeed reveals a history of entrepreneurial behavior at multiple levels within the firms.9 In addition, many of the firms traded on the NASDAQ, such as Amgen, Intuit, Apple, and Green Mountain Coffee Roasters, are com- monly thought of as entrepreneurial firms. The NASDAQ is the largest U.S. electronic stock market, with nearly 5,000 companies listed on the exchange.

We want to note here that established firms with an orientation toward acting entrepreneurially practice corporate entrepreneurship.10 All firms fall along a conceptual continuum that ranges from highly conservative to highly entrepreneurial. The position of a firm on this continuum is referred to as its entrepreneurial intensity.11 As we mentioned previously, entrepreneurial firms are typically proactive innovators and are not averse to taking calculated risks. In contrast, conservative firms take more of a “wait and see” posture, are less innovative, and are risk averse.

One of the most persuasive indications of entrepreneurship’s importance to an individual or to a firm is the degree of effort undertaken to behave in an entrepreneurial manner. Firms with higher entrepreneurial intensity regularly look for ways to cut bureaucracy. For example, Virgin Group, the large British conglomerate, works hard to keep its units small and instill in them an entre- preneurial spirit. Virgin is one of the most recognized brands in Britain and is involved in businesses as diverse as airlines and music. In the following quote, Sir Richard Branson, the founder and CEO of Virgin, describes how his com- pany operates in an entrepreneurial manner:

Convention … dictates that “big is beautiful,” but every time one of our ventures gets too big we divide it up into smaller units. I go to the deputy managing director, the deputy sales director, and the deputy marketing director and say, “Congratulations. You’re now MD [managing director], sales director and marketing director—of a new company.” Each time we’ve done this, the people involved haven’t had much more work to do, but necessarily they have a greater incentive to perform and a greater zeal for their work. The results for us have been terrific. By the time we sold Virgin Music, we had as many as 50 subsidiary record companies, and not one of them had more than 60 employees.12

3. Why Do people become entrepreneurs?

The three primary reasons that people become entrepreneurs and start their own firms are to be their own boss, pursue their own ideas, and realize finan- cial rewards.

3.1. Be Their Own Boss

The first of these reasons—being one’s own boss—is given most commonly. This doesn’t mean, however, that entrepreneurs are difficult to work with or that they have trouble accepting authority. Instead, many entrepreneurs want to be their own boss because either they have had a long-time ambition to own their own firm or because they have become frustrated working in traditional jobs. The type of frustration that some entrepreneurs feel working in conventional jobs is exemplified by Wendy DeFeudis, the founder of VeryWendy, a company that makes customized social invitations. Commenting on how her experiences working for herself have been more satisfying than working for a large firm, DeFeudis remarked:

I always wanted to be my own boss. I felt confined by the corporate structure. I found it frustrating and a complete waste of time-a waste to have to sell my ideas to multiple people and attend all kinds of internal meetings before moving forward with a concept.13

Some entrepreneurs transition from a traditional job to owning their own business more gradually, by starting their business part time to begin with. While this approach isn’t possible in all situations, by starting a business part time individuals can gain valuable experience, tuck away the money they earn, and find out if they really like the business before deciding to leave their job. In some businesses, such as catering or financial planning, it takes time to build a client list. Some entrepreneurs will time their departure from their job with the point in time where their client list is large enough and profitable enough to support a full-time business.14

3.2. Pursue Their Own ideas

The second reason people start their own firms is to pursue their own ideas. Some people are naturally alert, and when they recognize ideas for new prod- ucts or services, they have a desire to see those ideas realized. Corporate en- trepreneurs who innovate within the context of an existing firm typically have a mechanism for their ideas to become known. Established firms, however, often resist innovation. When this happens, employees are left with good ideas that go unfulfilled.16 Because of their passion and commitment, some employees choose to leave the firm employing them in order to start their own business as the means to develop their own ideas.

This chain of events can take place in non-corporate settings, too. For exam- ple, some people, through a hobby, leisure activity, or just everyday life, recognize the need for a product or service that is not available in the marketplace. If the idea is viable enough to support a business, they commit tremendous time and energy to convert the idea into a part-time or full-time firm. In Chapters 2 and 3, we focus on how entrepreneurs spot ideas and determine if their ideas represent viable business opportunities.

An example of a person who left a job to pursue an idea is Melissa Pickering, the founder of iCreate to Educate, a company that is developing software apps that allows students to build, express, and share their creativity through animated videos. Pickering started her career as a mechanical engi- neer at Walt Disney Corp., a role that she said is more commnonly referred to as an imagineer or a roller coaster engineer. She was struck by the fact that even at Dinsey, a place that some may refer to as the ultimate creative group, there weren’t many people who were female or close to her own age, and young engineers didn’t seem to be seeking out a Disney career. Her attention shifted to creativity and kids. Commenting on what happened next, she said:

My hunch was kids are not getting enough hands-on opportunities in the class- room to express and engage their creativity and problem solving skills. At that point I sought to launch an education technology business that would provide kids with the tools to create and explore, fostering the natural innovator within.17

iCreate to Eductate is currently building a portfolio of products, which includes both an iPhone and an iPad app. All of the firm’s products are centered on help- ing kids better develop and express their creativity.18

3.3. Pursue Financial Rewards

Finally, people start their own firms to pursue financial rewards. This motiva- tion, however, is typically secondary to the first two and often fails to live up to its hype. The average entrepreneur does not make more money than some- one with a similar amount of responsibility in a traditional job. The financial lure of entrepreneurship is its upside potential. People such as Jeff Bezos of Amazon.com, Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook, and Larry Page and Sergey Brin of Google made hundreds of millions of dollars building their firms. Money is also a unifier. Making a profit and increasing the value of a company is a solidifying goal that people can rally around. But money is rarely the primary motivation behind the launch of an entrepreneurial firm. Some entrepreneurs even report that the financial rewards associated with entrepreneurship can be bittersweet if they are accompanied by losing control of their firm. For ex- ample, Sir Richard Branson, after selling Virgin Records, wrote, “I remember walking down the street [after the sale was completed]. I was crying. Tears … [were] streaming down my face. And there I was holding a check for a billion dollars…. If you’d have seen me, you would have thought I was loony. A billion dollars.”19 For Branson, it wasn’t just the money—it was the thrill of building the business and of seeing the success of his initial idea.

Source: Barringer Bruce R, Ireland R Duane (2015), Entrepreneurship: successfully launching new ventures, Pearson; 5th edition.

Thank you for the auspicious writeup. It in fact was a amusement account it. Look advanced to far added agreeable from you! By the way, how could we communicate?