According to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), a franchise exists any time that the operations of a business involve (1) the selling of goods or services that bear a trademark, (2) the retention of significant control or assistance by the holder of the trademark on the operation of the business, and (3) royalty pay- ments by the purchaser of the business to the owner of the trademark for the right to use the trademark in the business.

The legal and regulatory environment surrounding franchising is based on the premise that the public interest is served if prospective franchisees are as informed as possible regarding the characteristics of a particular franchisor. The offer and sale of a franchise is regulated at both the state and the federal level. The legal aspects of the franchise relationship are unique enough that some attorneys specialize in franchise law.

1. Federal rules and regulations

Except for the automobile and petroleum industries, federal laws do not di- rectly address the franchisor–franchisee relationship. Instead, franchise dis- putes are matters of contract law and are litigated at the state level. During the 1990s, Congress considered several proposals for federal legislation to govern franchise relationships, but none became law.

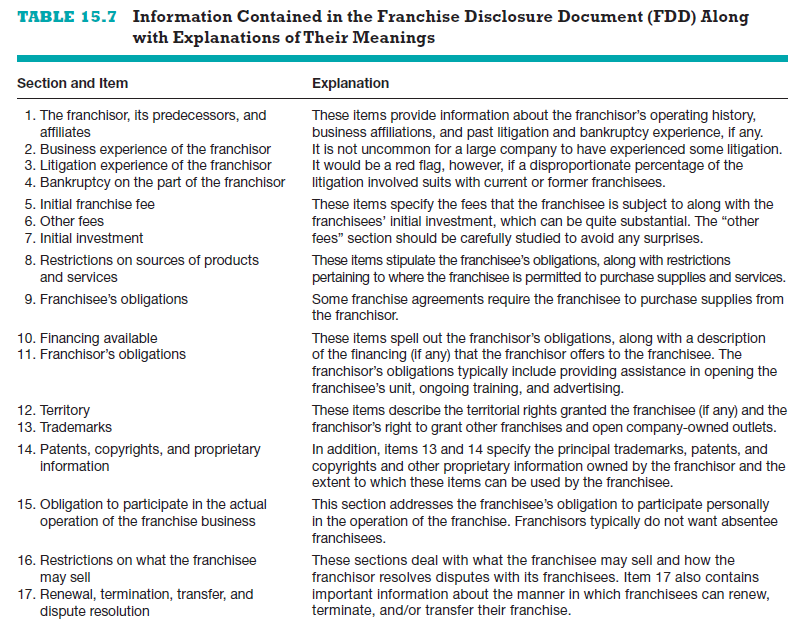

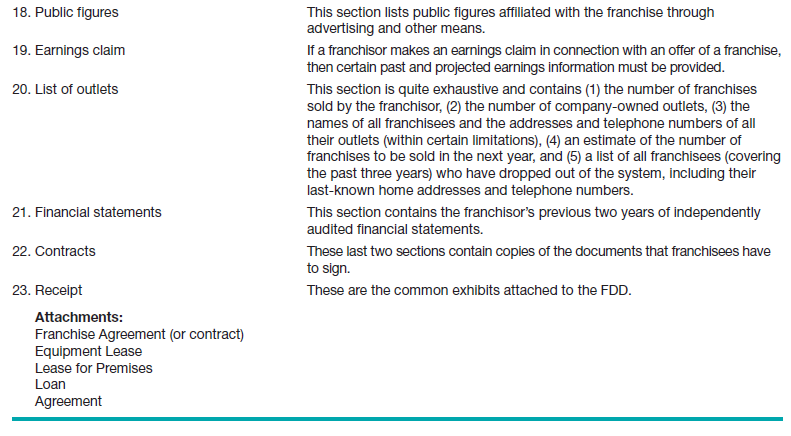

However, the offer and sale of a franchise is regulated at the federal level. Under the Franchise Rule, which is enforced by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), franchisors must furnish potential franchisees with written disclosures that provide information about the franchisor, the franchised business, and the franchise relationship. The disclosures must be supplied at least 14 busi- ness days before a franchise agreement can be signed or the franchisee pays the franchisor any money.22 In most cases, the disclosures are made through a lengthy document referred to as the Franchise Disclosure Document, which is accepted in all 50 states and parts of Canada. The Franchise Disclosure Document (FDD) contains 23 categories of information that give a prospective franchisee a broad base of information about the background and financial health of the franchisor. A summary of the information contained in the FDD is provided in Table 15.7. A prospective franchisee should fully understand all the information contained in the FDD before a franchise agreement is signed.

The FDD requires the franchisor to attach a copy of the franchise agreement and any other related contractual documents to the circular. The franchise agreement, or contract, is the document that consummates the sale of a fran- chise. Franchise agreements vary, but each agreement typically contains two sections: the purchase agreement and the franchise or license agreement. The purchase agreement typically spells out the price, the services to be provided by the franchisor to the franchisee, and the “franchise package,” which refers to all the items the franchisee has been told to expect. The franchise or license agree- ment typically stipulates the rights granted to the franchisee (including the right to use the franchisor’s trademark), the obligations and duties of the franchisor, the obligations and duties of the franchisee, trade restrictions, rights and limi- tations regarding the transfer or termination of the franchise agreement, and who is responsible for attorney fees if disputes arise. Most states have enacted a statute of frauds that requires franchise agreements to be in writing.

The federal government does not require franchisors to register with the FTC. The offer of a franchise for sale does not imply that the FTC has examined the franchisor and has determined that the information contained in the franchisor’s FDD is accurate. The franchisor is responsible for voluntarily complying with the law, and it is the responsibility of prospective franchisees to exercise due diligence in investigating franchise opportunities. Although most franchisor–franchisee re- lationships are conducted in an entirely ethical manner, it is a mistake to assume that a franchisor has a fiduciary obligation to its franchisees. What this means is that if a franchisor had a fiduciary obligation to its franchisees, it would always act in their best interest, or be on the franchisees’ “side.” Commenting on this is- sue, Robert Purvin, an experienced franchise attorney, wrote:

While the conventional wisdom talks about the proactive relationship of the fran- chisor to its franchisees, virtually every court case decided in the U.S. has ruled that a franchisor has no fiduciary obligation to its franchisees. Instead, U.S. courts have agreed with franchisors that franchise agreements are “arms length” business transactions.23

Purvin’s statement suggests that a potential franchisee should not rely solely on the goodwill of a franchisor when negotiating a franchise agreement. A po- tential franchisee should have a lawyer who is fully acquainted with franchise law and should closely scrutinize all franchise-related legal documents.

2. State rules and regulations

In addition to the FTC disclosure requirements, 15 states have franchise in- vestment laws that provide additional protection to potential franchisees.24

The states are California, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, North Dakota, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin. The franchise investment laws require franchisors to provide presale disclosures, known as “offering circulars,” to potential franchisees. Thirteen of the states have laws that treat the sale of a franchise like the sale of a security. These states require that a franchisor’s FDD be filed with a designated state agency and be placed into public record.

By requiring franchisors to file their FDDs with a state agency, these states provide franchise purchasers important legal protection, including the right to sue a franchisor for violation of state disclosure requirements (if the franchise purchaser feels that full disclosure in the offering circular was not made). For example, if someone purchased a franchise in one of the states fitting the pro- file described previously and six months later discovered that the franchisor did not disclose an issue required by the FDD (and, as a result, felt that he or she had been damaged), that person could seek relief by suing the franchisor in state court. All 15 states providing additional measures of protection for franchisees also regulate some aspect of the termination process. Although the provisions vary by state, they typically restrict a franchisor from terminating the franchise before the expiration of the franchise agreement, unless the fran- chisor has “good cause” for its action.

Although not as comprehensive as in the United States, at least 24 coun- tries now have laws regulating franchising in some manner. Australia, Brazil, Romania, South Korea, and Spain are five of these countries.25

Source: Barringer Bruce R, Ireland R Duane (2015), Entrepreneurship: successfully launching new ventures, Pearson; 5th edition.

This is a very good tips especially to those new to blogosphere, brief and accurate information… Thanks for sharing this one. A must read article.

Thanks for ones marvelous posting! I certainly enjoyed reading it, you will be a great author.I will make certain to bookmark your blog and may come back in the future. I want to encourage you to continue your great work, have a nice day!