Many people who are promoted into a manager position have little idea what the job actually entails and receive little training about how to handle their new role. It’s no wonder that, among managers, first-line supervisors tend to experience the most job burnout and attrition.23

Making the shift from individual contributor to manager is often tricky. Mark Zuckerberg, whose company, Facebook, went public a week before he turned 28 years old, provides an example. In a sense, the public has been able to watch as Zuckerberg has “grown up” as a manager. He was a strong individual performer in creating the social media platform and forming the company, but he fumbled with day-to-day management, such as interactions with employees and communicating with people both inside and outside Facebook. Zuckerberg was smart enough to hire seasoned managers, including former Google executive Sheryl Sandberg, and cultivate advisors and mentors who have coached him in areas where he is weak. He also shadowed David Graham at the offices of The Post Company (the publisher of The Washington Post before it was purchased by Jeff Bezos) for four days to try to learn what it is like to manage a large organization. Now that Facebook is a public company, Zuckerberg is watched more closely than ever to see if he has what it takes to be a manager of a big public corporation.24

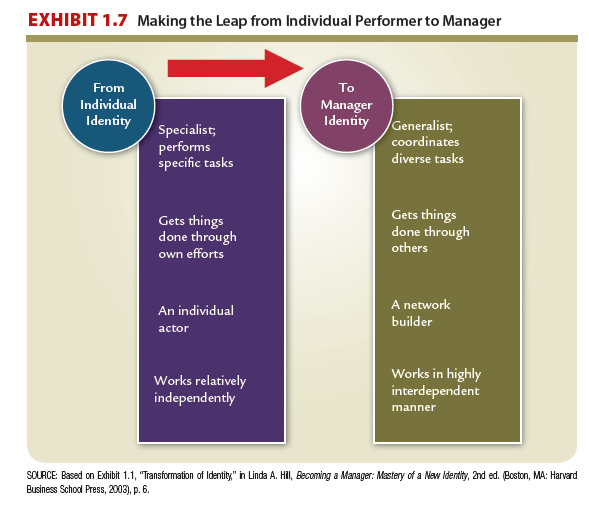

Harvard professor Linda Hill followed a group of 19 managers over the first year of their managerial careers and found that one key to success is to recognize that becoming a manager involves more than learning a new set of skills. Rather, becoming a manager means a profound transformation in the way people think of themselves, called personal identity, which includes letting go of deeply held attitudes and habits and learning new ways of thinking.25 Exhibit 1.7 outlines the transformation from individual performer to manager. The individual performer is a specialist and a “doer.” His or her mind is conditioned to think in terms of performing specific tasks and activities as expertly as possible. The manager, on the other hand, has to be a generalist and learn to coordinate a broad range of activities. Whereas the individual performer strongly identifies with his or her specific tasks, the manager has to identify with the broader organization and industry.

In addition, the individual performer gets things done mostly through his or her own efforts and develops the habit of relying on self rather than others. The manager, though, gets things done through other people. Indeed, one of the most common mistakes that new managers make is wanting to do all the work themselves, rather than delegating to others and developing others’ abilities.26 Hill offers a reminder that, as a manager, you must “be an instrument to get things done in the organization by working with and through others, rather than being the one doing the work.”27

Another problem for many new managers is that they expect to have greater freedom to do what they think is best for the organization. In reality, though, managers find themselves hemmed in by interdependencies. Being a successful manager means thinking in terms of building teams and networks and becoming a motivator and organizer within a highly interdependent system of people and work.28 Although the distinctions may sound simple in the abstract, they are anything but. In essence, becoming a manager means becoming a new person and viewing oneself in a completely new way.

Many new managers have to make the transformation in a “trial by fire,” learning on the job as they go, but organizations are beginning to be more responsive to the need for new manager training. The cost to organizations of losing good employees who can’t make the transition is greater than the cost of providing training to help new managers cope, learn, and grow. In addition, some organizations use great care in selecting people for managerial positions, including ensuring that each candidate understands what management involves and really wants to be a manager.

Source: Daft Richard L., Marcic Dorothy (2009), Understanding Management, South-Western College Pub; 8th edition.

I like this site its a master peace ! Glad I detected this on google .

I have read a few good stuff here. Definitely worth bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how much effort you put to make such a wonderful informative site.