One reason for the growing use of teams and networks is that many companies are recog- nizing the limits of traditional vertical organization structures in today’s fast-shifting envi- ronment. In general, the trend is toward breaking down barriers between departments, and many companies are moving toward horizontal structures based on work processes rather than departmental functions.48 However, regardless of the type of structure, every organi- zation needs mechanisms for horizontal integration and coordination. The structure of an organization is not complete without designing the horizontal as well as the vertical di- mensions of structure.49

1. THE NEED FOR COORDINATION

As organizations grow and evolve, two things happen. First, new positions and depart- ments are added to deal with factors in the external environment or with new strategic needs. For example, in recent years, most colleges and universities established in-house legal departments to cope with increasing government regulations and a greater threat of lawsuits in today’s society. Whereas small schools once relied on outside law firms, legal counsel is now considered crucial to the everyday operation of a college or university.50

Many organizations establish IT departments to manage the proliferation of new informa- tion systems. As companies add positions and departments to meet changing needs, they grow more complex, with hundreds of positions and departments performing incredibly diverse activities.

Second, senior managers have to find a way to tie all of these departments together. The formal chain of command and the supervision it provides is effective, but it is not enough. The organization needs systems to process information and enable communication among people in different departments and at different levels. Coordination refers to the quality of collaboration across departments. Without coordination, a company’s left hand will not act in concert with the right hand, causing problems and conflicts. Coordination is required regardless of whether the organization has a functional, divisional, or team structure.

Without a major effort at coordination, an organization may be like Chrysler Corpora- tion in the 1980s when Lee Iacocca took over:

What I found at Chrysler were 35 vice presidents, each with his own turf. . . . I couldn’t believe, for example, that the guy running engineering departments wasn’t in constant touch with his counterpart in manufacturing. But that’s how it was. Everybody worked independently. I took one look at that system, and I almost threw up. That’s when I knew I was in really deep trouble.

I’d call in a guy from engineering, and he’d stand there dumbfounded when I’d explain to him that we had a design problem or some other hitch in the engineering- manufacturing relationship. He might have the ability to invent a brilliant piece of engineering that would save us a lot of money. He might come up with a terrific new design. There was only one problem: He didn’t know that the manufacturing people couldn’t build it. Why? Because he had never talked to them about it. Nobody at Chrysler seemed to understand that interaction among the different functions in a company is absolutely critical. People in engineering and manufacturing almost have to be sleeping together. These guys weren’t even flirting!51

If one thing changed at Chrysler in the years before Iacocca retired, it was improved coor- dination. Cooperation among engineering, marketing, and manufacturing enabled the rapid design and production of the Chrysler PT Cruiser, for example.

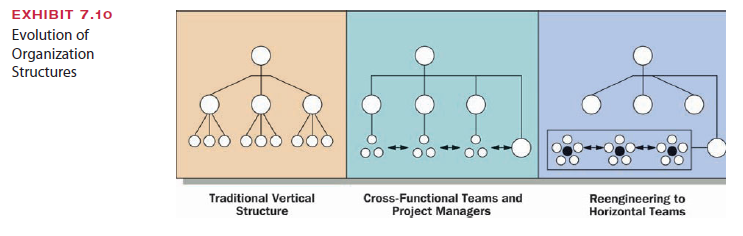

The problem of coordination is amplified in the international arena because organiza- tional units are differentiated not only by goals and work activities but by geographical distance, time differences, cultural values, and perhaps language as well. How can manag- ers ensure that needed coordination will take place in their company, both domestically and globally? Coordination is the outcome of information and cooperation. Managers can de- sign systems and structures to promote horizontal coordination. For example, to support its global strategy, Whirlpool decentralized its operations, giving more authority and respon- sibility to teams of designers and engineers in developing countries such as Brazil, and es- tablished outsourcing relationships with manufacturers in China and India.52 Exhibit 7.10 illustrates the evolution of organizational structures, with a growing emphasis on horizon- tal coordination. Although the vertical functional structure is effective in stable environ- ments, it does not provide the horizontal coordination needed in times of rapid change. Innovations such as cross-functional teams, task forces, and project managers work within the vertical structure but provide a means to increase horizontal communication and coop- eration. The next stage involves reengineering to structure the organization into teams working on horizontal processes. The vertical hierarchy is flattened, with perhaps only a few senior executives in traditional support functions such as finance and human resources. Challenges with international structures are illustrated in the following Business Blooper about Starbucks.

2. TASK FORCES, TEAMS, AND PROJECT MANAGEMENT

A task force is a temporary team or committee designed to solve a short- term problem involving several depart- ments.53 Task force members represent their departments and share informa- tion that enables coordination. For example, the Shawmut National Corpo- ration created a task force in human resources to consolidate all employment services into a single area. The task force looked at job banks, referral programs, employment procedures, and applicant tracking systems; found ways to perform these functions for all Shawmut’s divi- sions in one human resource depart- ment; and then disbanded.54 In addition to creating task forces, companies also set up cross-functional teams, as described earlier. A cross-functional team furthers horizontal coordination because partici- pants from several departments meet regularly to solve ongoing problems of common interest.55 This team is similar to a task force except that it works with continuing rather than temporary prob- lems and might exist for several years.

Team members think in terms of working together for the good of the whole rather than just for their own department. For example, top executives at one large consumer products company had to hold frequent marathon meetings to resolve conflicts among functional units. Functional managers were focused on achieving departmental goals and were en- gaged in little communication across units. Resolving the conflicts that arose was time- consuming and arduous for everyone involved. Establishing a cross-functional team solved the problem by ensuring regular horizontal communication and cooperation regarding common issues and problems.56

Companies also use project managers to increase coordination between functional de- partments. A project manager is a person who is responsible for coordinating the activi- ties of several departments for the completion of a specific project.57 Project managers are critical today because many organizations are continually reinventing themselves, creating flexible structures, and working on projects with an ever-changing assortment of people and organizations.58 Project managers might work on several different projects at one time and might have to move in and out of new projects at a moment’s notice.

The distinctive feature of the project manager position is that the person is not a member of one of the departments being coordinated. Project managers are located outside of the departments and have responsibility for coordinating several depart- ments to achieve desired project outcomes. For example, General Mills, Procter & Gamble, and General Foods all use product managers to coordinate their product lines. A manager is assigned to each line, such as Cheerios, Bisquick, and Hamburger Helper. Product managers set budget goals, marketing targets, and strategies, and obtain the cooperation from advertising, production, and sales personnel needed for implementing product strategy.

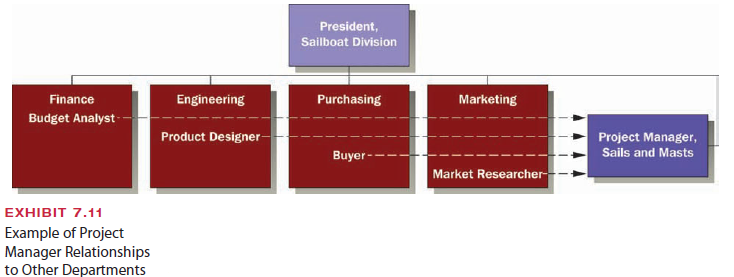

In some organizations, project managers are included on the organization chart, as illustrated in Exhibit 7.11. The project manager is drawn to one side of the chart to indi- cate authority over the project but not over the people assigned to it. Dashed lines to the project manager indicate responsibility for coordination and communication with assigned team members, but department managers retain line authority over functional employees.

Project managers might also have titles such as product manager, integrator, program manager, or process owner. Project managers need excellent people skills.

They use expertise and persuasion to achieve coordination among various departments, and their jobs involve getting people together, listening, building trust, confronting prob- lems, and resolving conflicts and disputes in the best interest of the project and the organi- zation. Many organizations move to a stronger horizontal approach such as the use of permanent teams, project managers, or process owners after going through a redesign pro- cedure called reengineering.

3. REENGINEERING

Reengineering, sometimes called business process reengineering, is the radical redesign of business processes to achieve dramatic improvements in cost, quality, service, and speed.59 Because the focus of reengineering is on process rather than function, reengi- neering generally leads to a shift away from a strong vertical structure to one emphasizing stronger horizontal coordination and greater flexibility in responding to changes in the environment.

Reengineering changes the way managers think about how work is done in their orga- nizations. Rather than focusing on narrow jobs structured into distinct, functional depart- ments, they emphasize core processes that cut horizontally across the company and involve teams of employees working to provide value directly to customers.60 A process is an orga- nized group of related tasks and activities that work together to transform inputs into outputs and create value. Common examples of processes include new product development, order fulfillment, and customer service.61

Reengineering frequently involves a shift to a horizontal team-based structure, as de- scribed earlier in this chapter. All the people who work on a particular process have easy access to one another so they can easily communicate and coordinate their efforts, share knowledge, and provide value directly to customers.62 For example, reengineering at Texas Instruments led to the formation of product development teams that became the funda- mental organizational unit. Each team is made up of people drawn from engineering, mar- keting, and other departments, and takes full responsibility for a product from conception through launch.63

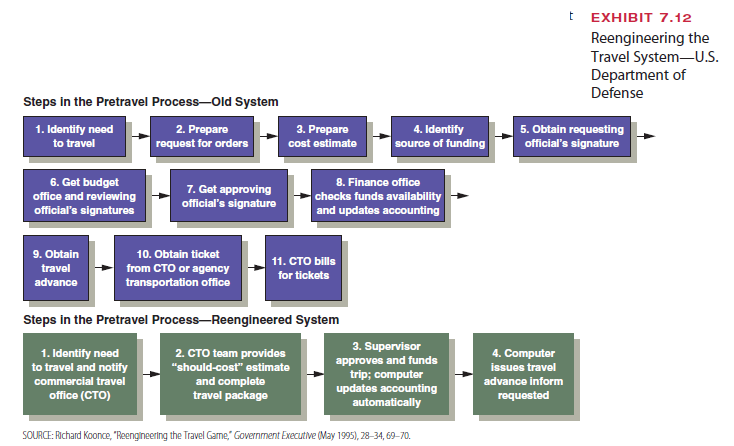

Reengineering can also squeeze out the dead space and time lags in work flows, as illustrated by reengineering of the travel system at the U.S. Department of Defense.

As illustrated by this example, reengineering can lead to stunning results, but, like all business ideas, it has its drawbacks. Simply defining the organization’s key business processes can be mind-boggling. AT&T’s Network Systems division started with a list of 130 processes and then began working to pare them down to 13 core ones.65 Organizations often have difficulty realigning power relationships and management processes to support work redesign and thus do not reap the intended benefits of reengineering. According to some estimates, 70 percent of reengineering efforts fail to reach their intended goals.66

Because reengineering is expensive, time consuming, and usually painful, it seems best suited to companies that are facing serious competitive threats.

Source: Daft Richard L., Marcic Dorothy (2009), Understanding Management, South-Western College Pub; 8th edition.

There is visibly a bundle to identify about this. I believe you made various good points in features also.