Many managers are concerned with improving the ethical climate and social responsive- ness of their companies. As one expert on the topic of ethics said, “Management is respon- sible for creating and sustaining conditions in which people are likely to behave themselves.”60

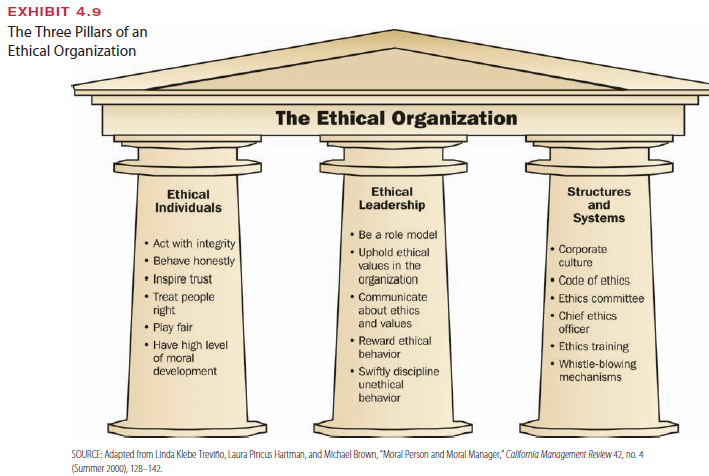

Managers can take active steps to ensure that the company stays on an ethical footing. As discussed earlier in this chapter, ethical business practices depend on individual managers as well as the organization’s values, policies, and practices. Exhibit 4.9 illustrates the three pillars that support an ethical organization.61

1. ETHICAL INDIVIDUALS

Managers who are essentially ethical individuals make up the first pillar. These individuals possess honesty and integrity, which is reflected in their behavior and decisions. People inside and outside the organization trust them because they can be relied upon to follow the standards of fairness, treat people right, and be ethical in their dealings with others. Ethical individuals strive for a high level of moral development, as discussed earlier in the chapter.

Being a moral person and making ethical decisions is not enough, though. Ethical man-agers also encourage the moral development of others.62 They find ways to focus the entire organization’s attention on ethical values and create an organizational environment that encourages, guides, and supports the ethical behavior of all employees. Two additional pil- lars are needed to provide a strong foundation for an ethical organization: ethical leader- ship and organizational structures and systems.

2. ETHICAL LEADERSHIP

In a study of ethics policy and practice in successful ethical companies, no point emerged more clearly than the crucial role of leadership.63 If people don’t hear about ethical values from top leaders, they get the idea that ethics is not important in the organization. Employees are acutely aware of their leaders’ ethical lapses, and the company grapevine quickly commu- nicates situations in which top managers choose an expedient action over an ethical one.64

Lower-level managers and first-line supervisors perhaps are even more important as role models for ethical behavior, because they are the leaders whom employees see and work with on a daily basis. These managers can strongly influence the ethical climate in the organization by adhering to high ethical standards in their own behavior and deci- sions. In addition, these leaders articulate the desired ethical values and help others em- body and reflect those values.65

Using performance reviews and rewards effectively is a powerful way for managers to signal that ethics counts. Managers also take a stand against unethical behavior. Consis- tently rewarding ethical behavior and disciplining unethical conduct at all levels of the company is a critical component of providing ethical leadership.66

Kathryn Reimann, a senior vice president at American Express, recalls the impact one senior executive had on the ethical tone of the organization. The leader heard reports that one of the company’s top performers was mistreating subordinates. After he verified the reports, the executive publicly fired the manager and emphasized that no amount of busi- ness success could make up for that kind of behavior. The willingness to fire a top per- former because of his unethical treatment of employees made a strong statement that ethics was important at American Express.67

3. ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURES AND SYSTEMS

The third pillar of ethical organizations is the set of tools that managers use to shape values and promote ethical behavior throughout the organization. Three of these tools are codes of ethics, ethical structures, and mechanisms for supporting whistle-blowers.

Code of Ethics. A code of ethics is a formal statement of the company’s values concerning ethics and social issues. It communicates to employees what the company stands for. Codes of ethics tend to exist as two types: principle-based statements and policy- based statements.

Principle-based statements are designed to affect corporate culture; they define funda- mental values and contain general language about company responsibilities, quality of products, and treatment of employees. General statements of principle are often called corporate credos. A good example is Johnson & Johnson’s “The Credo.”

Policy-based statements generally outline the procedures to be used in specific ethical situations. These situations include marketing practices, conflicts of interest, observance of laws, proprietary information, political gifts, and equal opportunities. Examples of policy- based statements are Boeing’s “Business Conduct Guidelines,” Chemical Bank’s “Code of Ethics,” GTE’s “Code of Business Ethics” and “Anti-Trust and Conflict of Interest Guide- lines,” and Norton’s “Norton Policy on Business Ethics.”68

Codes of ethics state the values or behaviors expected and those that will not be toler-ated, backed up by management action. Because of the number of scandals in the financial services industry, a group convened by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences sug- gested that Wall Street should have a broad ethics code similar to the millennia-old Hip- pocratic oath for doctors. With numerous areas open to ethical abuses and the pressures that investment bankers face when millions of dollars are at stake, the group, which in- cludes some of the most respected leaders on Wall Street, believes a code could serve as a guide for managers facing thorny ethical issues.69

Many financial institutions, of course, have their own individual corporate codes. A survey of Fortune 1,000 companies found that 98 percent address issues of ethics and busi- ness conduct in formal corporate documents, and 78 percent of those have separate codes of ethics that are widely distributed.70 When top management supports and enforces these codes, including rewards for compliance and discipline for violation, ethics codes can boost a company’s ethical climate.71 The code of ethics for The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel gives employees some guidelines for dealing with ethical questions.72

By giving people some guidelines for confronting ethical questions and promising protection from recriminations for people who report wrongdoing, the Journal’s code of ethics gives all employees the responsibility and the right to maintain the organization’s ethical climate.

4. ETHICAL STRUCTURES

Ethical structures represent the various systems, positions, and programs a company can undertake to implement ethical behavior. An ethics committee is a group of executives appointed to oversee company ethics. The committee provides rulings on questionable ethical issues. The ethics committee assumes responsibility for disciplining wrongdoers, which is essential if the organization is to directly influence employee behavior.

For example, Motorola’s Ethics Compliance Committee is charged with interpreting, clarifying, and communicating the company’s code of ethics and with adjudicating suspected code violations. Many companies, such as Sears, Northrop Grumman, and Columbia/ HCA Healthcare, set up ethics offices with full-time staff to ensure that ethical standards are an integral part of company operations. These offices are headed by a chief ethics officer, a company executive who oversees all aspects of ethics and legal compliance, in- cluding establishing and broadly communicating standards, ethics training, dealing with exceptions or problems, and advising senior managers in the ethical and compliance aspects of decisions.73

The title of chief ethics officer was almost unheard of a decade ago, but highly publi- cized ethical and legal problems faced by companies in recent years sparked a growing demand for these ethics specialists. The Ethics and Compliance Officers Association, a trade group, reports that membership soared to more than 1,250 companies, up from about half that number in 2002.74 Most ethics offices also work as counseling centers to help employees resolve difficult ethical issues. A toll-free confidential hotline allows employees to report questionable behavior as well as seek guidance concerning ethical dilemmas.

Ethics training programs also help employees deal with ethical questions and trans-late the values stated in a code of ethics into everyday behavior.75 Training programs are an important supplement to a written code of ethics. General Electric implemented a strong compliance and ethics training program for all 320,000 employees worldwide. Much of the training is conducted online, with employees able to test themselves on how they would handle thorny ethical issues.

In addition, small-group meetings give people a chance to ask questions and discuss ethical dilemmas or questionable actions. Every quarter, each of GE’s business units reports to headquarters the percentage of division employees who completed training sessions and the percentage that have read and signed off on the company’s ethics guide, “Spirit and Letter.”76

At McMurray Publishing Company in Phoenix, all employees attend a weekly meeting on workplace ethics. In these meetings the discussion centers on how to handle ethical di- lemmas and how to resolve conflicting values.77

A strong ethics program is important, but it is no guarantee against lapses. Enron could boast of a well-developed ethics program, for example, but managers failed to live up to it. Enron’s problems sent a warning to other managers and organizations. It is not enough to have an impressive ethics program. The ethics program must be merged with day-to-day operations, encouraging ethical decisions throughout the company.

5. WHISTLE-BLOWING

Employee disclosure of illegal, immoral, or illegitimate practices on the employer’s part is called whistle-blowing.78 No organization can rely exclusively on codes of conduct and ethical structures to prevent all unethical behavior.

Holding organizations accountable depends to some extent on individuals who are will- ing to blow the whistle if they detect illegal, dangerous, or unethical activities. Whistle- blowers often report wrongdoing to outsiders, such as regulatory agencies, senators, or newspaper reporters. Some firms have instituted innovative programs and confidential hotlines to encourage and support internal whistle-blow-ing. For this practice to be an effective ethical safeguard, however, companies must view whistle-blowing as a ben- efit to the company and make dedicated efforts to protect whistle-blowers.79

Without effective protective measures, whistle-blow- ers suffer. Although whistle-blowing has become wide- spread in recent years, it still is risky for employees, who can lose their jobs, be ostracized by co-workers, or be transferred to lower-level positions. Consider what hap- pened when Linda Kimble reported that the car rental agency where she worked was pushing the sale of insur- ance to customers who already had coverage. Within a few weeks after making the complaint to top managers, Kimble was fired.

The 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley Act provides some safety for whistle-blowers like Kimble. People fired for report- ing wrongdoing can file a complaint under the law and are eligible for back pay, attorney’s fees, and a chance to get their old job back, as Kimble did. The impact of the legislation is still unclear, but many whistle-blowers fear that they will suffer even more hostility if they return to the job after winning a case under Sarbanes-Oxley.80

Many managers still look upon whistle-blowers as dis- gruntled employees who aren’t good team players. Yet, to maintain high ethical standards, organizations need people who are willing to point out wrongdoing. Managers can be trained to view whistle-blowing as a benefit rather than a threat, and systems can be set up to effectively protect employees who report illegal or un- ethical activities.

Source: Daft Richard L., Marcic Dorothy (2009), Understanding Management, South-Western College Pub; 8th edition.

There is noticeably a lot to identify about this. I assume you made certain nice points in features also.