Managers do make some decisions as individuals, but decision makers more often are part of a group. Major decisions in the business world rarely are made entirely by an individual. Effective decision making often depends on whether managers involve the right people in the right ways in helping to solve problems. One model that provides guidance for practic- ing managers was originally developed by Victor Vroom and Arthur Jago.51

1. THE VROOM-JAGO MODEL

The Vroom-Jago model helps a manager gauge the appropriate amount of participation by subordinates in making a specific decision. The model has three major components: leader participation styles, a set of diagnostic questions with which to analyze a decision situation, and a series of decision rules.

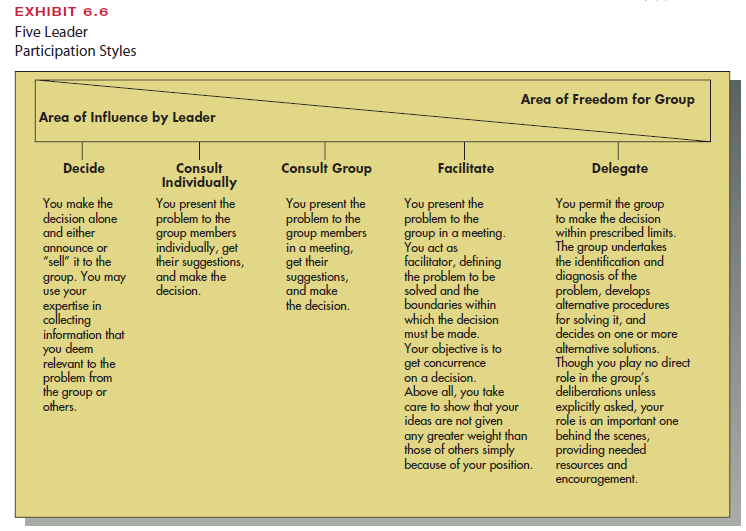

Leader Participation Styles. The model employs five levels of subordinate participation in decision making, ranging from highly autocratic (leader decides alone) to highly democratic (leader delegates to group), as illustrated in Exhibit 6.6.52 The exhibit shows five decision styles, starting with the leader making the decision alone (Decide);

presenting the problem to subordinates individually for their suggestions and then making the decision (Consult Individually); presenting the problem to subordinates as a group, collectively obtaining their ideas and suggestions, then making the decision(Consult Group); sharing the problem with subordinates as a group and acting as a facilitator to help the group arrive at a decision (Facilitate); or delegating the problem and permitting the group to make the decision within prescribed limits (Delegate).

Diagnostic Questions. How does a manager decide which of the five decision styles to use? The appropriate degree of decision participation depends on a number of situa- tional factors, such as the required level of decision quality, the level of leader or subordinate expertise, and the importance of having subordinates commit to the decision. Leaders can analyze the appropriate degree of participation by answering seven diagnostic questions.

- Decision significance: How significant is this decision for the project or organization? If the quality of the decision is highly important to the success of the project or organization, the leader has to be actively involved.

- Importance of commitment: How important is subordinate commitment to carrying out the decision? If implementation requires a high level of commitment to the decision, leaders should involve subordinates in the decision process.

- Leader expertise: What is the level of the leader’s expertise in relation to the problem? If the leader does not have a high amount of information, knowledge, or expertise, the leader should involve subordinates to obtain it.

- Likelihood of commitment: If the leader were to make the decision alone, would subordinates have high or low commitment to the decision? If subordinates typically go along with what- ever the leader decides, their involvement in the decision-making process will be less important.

- Group support for goals: What is the degree of subordinate support for the team’s or organiza- tion’s objectives at stake in this decision? If subordinates have low support for the goals of the organization, the leader should not allow the group to make the decision alone.

- Group expertise: What is the level of group members’ knowledge and expertise in relation to the problem? If subordinates have a high level of expertise in relation to the problem, more responsibility for the decision can be delegated to them.

- Team competence: How skilled and committed are group members to working together as a team to solve problems? When subordinates have high skills and high desire to work to- gether cooperatively to solve problems, more responsibility for decision making can be delegated to them.

These questions seem detailed, but considering these seven situational factors can quickly narrow the options and point to the appropriate level of group participation in deci- sion making.

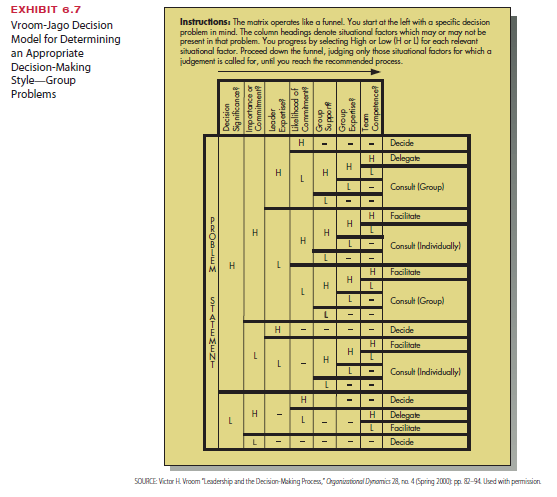

Selecting a Decision Style. The decision matrix in Exhibit 6.7 allows a manager to adopt a participation style by answering the diagnostic questions in se- quence. The manager enters the matrix at the left-hand side, at Problem Statement, and considers the seven situational questions in sequence from left to right, answering high (H) or low (L) to each one and avoiding crossing any horizontal lines. The first question would be: How significant is this decision for the project or organization? If the answer is High, the leader proceeds to importance of commitment: How important is subordinate commitment to carrying out the decision? An answer of High leads to a ques- tion about leader expertise: What is the level of the leader’s expertise in relation to the problem? If the leader’s knowledge and expertise is High, the leader next considers likelihood of commitment: If the leader were to make the decision alone, how likely is it that subordinates would be committed to the decision? A high likelihood that subordinates would be committed means the decision matrix leads directly to the Decide style of decision making, in which the leader makes the decision alone and presents it to the group.

The Vroom-Jago model has been criticized as being less than perfect,53 but it is useful to managers, and the body of supportive research is growing.54 Managers can use the model to make timely, high-quality decisions. Consider the application of the model to the fol- lowing hypothetical problem.

The Vroom-Jago model in Exhibit 6.7 shows that Robbins used the correct decision style. Moving from left to right in Exhibit 6.7, the questions and answers are as fol- lows: How significant is the decision? Definitely high. The company’s future might be at stake. How important is subordinate commitment to the decision? Also high. The team members must support and implement Robbins’ solution. What is the level of Robbins’s information and expertise? Probably low. Even though he has spent several weeks re-searching the seized engines, other team members have additional information and ex- pertise that needs to be considered. If Robbins makes the decision on his own, would team members have high or low commitment to it? The answer to this question is probably also low. Even though team members respect Robbins, they take pride in their work as a team and know Robbins does not have complete information. This leads to the ques- tion, What is the degree of subordinate support for the team’s or organization’s objectives at stake in this decision? Definitely high. This leads to the question, What is the level of group members’ knowledge and expertise in relation to the problem? The answer to this question is low, which leads to the Consult Group decision style, as described earlier in Exhibit 6.6. Thus, Robbins used the style that would be recommended by the Vroom-Jago model.

In many situations, several decision styles might be equally acceptable. However, smart managers are encouraging greater employee participation in solving problems whenever possible. The use of new knowledge management technologies allows for accessing the ideas and knowledge of a much broader group of people, both inside and outside the orga- nization.56 Broad participation often leads to better decisions. Involving others in decision making also contributes to individual and organizational learning, which is critical for rapid decision making in a turbulent environment.

2. NEW DECISION APPROACHES FOR TURBULENT TIMES

The ability to make fast, widely supported, high-quality decisions on a frequent basis is a critical skill in today’s fast-moving organizations.57 In many industries, the rate of competi- tive and technological change is so extreme that opportunities are fleeting, clear and com- plete information is seldom available, and the cost of a slow decision means lost business or even company failure. Do these factors mean managers should make the majority of deci- sions on their own? No. The rapid pace of the business environment calls for just the opposite—that is, for people throughout the organization to be involved in decision mak- ing and have the information, skills, and freedom they need to respond immediately to problems and questions. Business is taking a lesson from today’s military. For example, the U.S. Army, once considered the ultimate example of a rigid, top-down organization, is pushing information and decision making to junior officers in the field. Fighting a fluid, fast-moving, and fast-changing terrorist network means that people who are knowledge- able about the local situation have to make quick decisions, learning through trial and error and sometimes departing from standard Army procedures. Junior leaders rely on a strong set of core values and a clear understanding of the mission to craft creative solutions to problems that the Army might never have encountered before.58

Similarly, in today’s fast-moving businesses, people often have to act first and analyze later.59 Top managers do not have the time to evaluate options for every decision, conduct research, develop alternatives, and tell people what to do and how to do it. When speed matters, a slow decision may be as ineffective as the wrong decision, and companies can learn to make decisions fast. Effective decision making under turbulent conditions relies on the following guidelines.

Start with Brainstorming. One of the best-known techniques for rapidly gen- erating creative alternatives is brainstorming. Brainstorming uses a face-to-face interac- tive group to spontaneously suggest a wide range of alternatives for decision making. The keys to effective brainstorming are that people can build on one another’s ideas; all ideas are acceptable, no matter how crazy they seem; and criticism and evaluation are not allowed. The goal is to generate as many ideas as possible. Brainstorming has been found to be highly effective for quickly generating a wide range of alternate solutions to a problem, but it does have some drawbacks. For one, people in a group often want to conform to what others are saying, a problem sometimes referred to as groupthink. Others may be concerned about pleasing the boss or impressing colleagues. In addition, many creative people simply have social inhibitions that limit their participation in a group session or make it difficult to come up with ideas in a group setting. In fact, one study found that when four people are asked to “brainstorm” individually, they typically come up with twice as many ideas as a group of four brainstorming together.

One approach, electronic brainstorming, takes advantage of the group approach while overcoming some disadvantages. Electronic brainstorming, sometimes called brain- writing, brings people together in an interactive group over a computer network.60 One member writes an idea, another reads it and adds other ideas, and so on. Studies show that electronic brainstorming generates about 40 percent more ideas than individuals brain- storming alone, and 25 to 200 percent more ideas than regular brainstorming groups, depending on group size.61 Why? Because the process is anonymous, so the sky’s the limit in terms of what people feel free to say. People can write down their ideas immediately, avoiding the possibility that a good idea might slip away while the person is waiting for a chance to speak in a face-to-face group. Social inhibitions and concerns are avoided, which typically allows for a broader range of participation. Another advantage is that electronic brainstorming can potentially be done with groups made up of employees from around the world, further increasing the diversity of alternatives.

Learn, Don’t Punish. Decisions made under conditions of uncertainty and time pressure produce many errors, but smart managers are willing to take the risk in the spirit of trial and error. If a chosen decision alternative fails, the organization can learn from it and try another alterna- tive that better fits the situation. Each failure provides new information and learning. People throughout the organi- zation are encouraged to engage in experi- mentation, which means taking risks and learning from their mistakes. Good man- agers know that every time a person makes a decision, whether it turns out to have positive or negative consequences, it helps the employee learn and be a better deci- sion maker the next time around. By making mistakes, people gain valuable experience and knowledge to perform more effectively in the future. PSS World Medical of Jacksonville, Florida, encour- ages people to take initiative and try new things with a policy of never firing anyone for an honest mistake. In addition, PSS promises to find another, more appropri-ate job in the company for any employee who is failing in his or her current position. This “soft landing” policy fosters a climate in which mistakes and failure are viewed as opportunities to learn and improve.62

When people are afraid to make mistakes, the company is stuck. For example, when Robert Crandall led American Airlines, he built a culture in which any problem that caused a flight delay was followed by finding someone to blame. People became so scared of mak- ing a mistake that whenever something went wrong, no one was willing to jump in and try to fix the problem. In contrast, Southwest Airlines uses what it calls team delay, which means a flight delay is everyone’s problem. This puts the emphasis on fixing the problem rather than on finding an individual to blame.63 In a turbulent environment, managers do not use mistakes and failure to create a climate of fear. Instead, they encourage people to take risks and move ahead with the decision process, despite the potential for errors.

Know When to Bail. Even though managers encourage risk taking and learning from mistakes, they also aren’t hesitant to pull the plug on something that is not working. Research found that organizations often continue to invest time and money in a solution despite strong evidence that it is not appropriate. This tendency is referred to as escalat- ing commitment. Managers might block or distort negative information because they don’t want to be responsible for a bad decision, or they might simply refuse to accept that their solution is wrong. A study in Europe verified that even highly successful managers often miss or ignore warning signals because they become committed to a decision and believe if they persevere it will pay off.64 As companies face increasing competition, com- plexity, and change, it is important that managers don’t get so attached to their own ideas that they’re unwilling to recognize when to move on. According to Stanford University professor Robert Sutton, the key to successful creative decision making is to “fail early, fail often, and pull the plug early.”65

Practice the Five Whys. One way to encourage good decision making under high uncertainty is to get people to think more broadly and deeply about problems rather than going with a superficial understanding and a first response. However, this approach doesn’t mean people have to spend hours analyzing a problem and gathering research. One simple procedure adopted by a number of leading companies is known as the five whys.66 For every problem, employees learn to ask “Why?” not just once, but five times. The first why generally produces a superficial explanation for the problem, and each subsequent why probes deeper into the causes of the problem and potential solutions. The point of the five whys is to improve how people think about problems and generate alternatives for solving them.

Engage in Rigorous Debate. An important key to better decision making under conditions of uncertainty is to encourage a rigorous debate of the issue at hand.67

Good managers recognize that constructive conflict based on divergent points of view can bring a problem into focus, clarify people’s ideas, stimulate creative thinking, create a broader understanding of issues and alternatives, and improve decision quality.68 Chuck Knight, the former CEO of Emerson Electric, always sparked heated debates during stra- tegic planning meetings. Knight believed rigorous debate gave people a clearer picture of the competitive landscape and forced managers to look at all sides of an issue, helping them reach better decisions.69

Stimulating rigorous debate can be done in several ways. One way is by ensuring that the group is diverse in terms of age and gender, functional area of expertise, hierarchical level, and experience with the business. Some groups assign a devil’s advocate, who has the role of challenging the assumptions and assertions made by the group.70 The devil’s ad- vocate may force the group to rethink its approach to the problem and avoid reaching pre- mature conclusions. Jeffrey McKeever, CEO of MicroAge, often plays the devil’s advocate, changing his position in the middle of a debate to ensure that other executives don’t just go along with his opinions.71 Another approach is to have group members develop as many alter- natives as they can as quickly as they can.72 It allows the team to work with multiple alternatives and encourages people to advocate ideas they might not prefer simply to encourage debate. Still another way to encourage constructive conflict is to use a technique called point-counterpoint, which breaks a decision-making group into two subgroups and assigns them different, often competing responsibilities.73 The groups then develop and exchange proposals and discuss and debate the various options until they arrive at a common set of understandings and recommendations.

Decision making in today’s high-speed, complex environment is one of the most important—and most challenging—responsibilities for managers. By using brainstorming, learning from mistakes rather than assigning blame, knowing when to bail, practicing the five whys, and engaging in rigorous debate, managers can improve the quality and effective- ness of their organizational decisions.

Source: Daft Richard L., Marcic Dorothy (2009), Understanding Management, South-Western College Pub; 8th edition.

I just could not go away your web site before suggesting that I actually loved the usual information a person supply for your visitors? Is going to be back steadily in order to check out new posts.