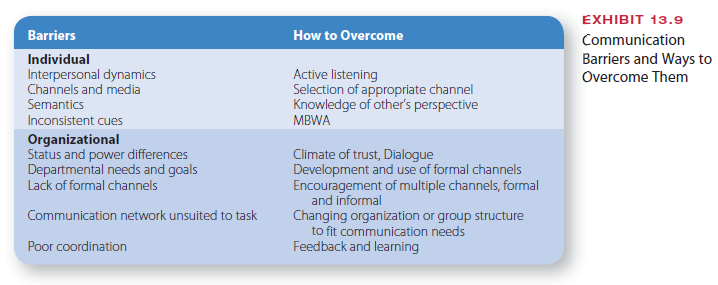

Many of the ideas described in this chapter pertain to barriers to communication and how to overcome them. Exhibit 13.9 lists some of the major barriers to communication, along with some techniques for overcoming them.

1. BARRIERS TO COMMUNICATION

Barriers can be categorized as those that exist at the individual level and those that exist at the organizational level.

Individual Barriers. First, interpersonal barriers include problems with emotions and perceptions held by employees. For example, rigid perceptual labeling or stereotyping prevents people from modifying or altering their opinions. If a person’s mind is made up before the communication starts, communication will fail. Moreover, people with different backgrounds or knowledge may interpret a communication in different ways.

Second, selecting the wrong channel or medium for sending a communication can be a problem. When a message is emotional, it is better to transmit it face to face rather than in writing. E-mail can be particularly risky for discussing difficult issues because it lacks the capacity for rapid feedback and multiple cues. On the other hand, e-mail is highly efficient for routine messages.

Third, semantics often causes communication problems. Semantics pertains to the meaning of words and the way they are used. A word such as effectiveness may mean achiev- ing high production to a factory superintendent, but to a human resources staff specialist, it might mean employee satisfaction. Many common words have an average of 28 defini- tions; thus, communicators must take care to select the words that will accurately encode ideas.81 Language differences can also be a barrier in today’s organizations. This chapter’s Spotlight boxed feature offers some guidelines for how managers can better communicate with people who speak a different language.

Fourth, sending inconsistent cues between verbal and nonverbal communications will confuse the receiver. If a person’s facial expression does not reflect his or her words, the communication will contain noise and uncertainty. The tone of voice and body language should be consistent with the words, and actions should not contradict words.

Organizational Barriers. Organizational barriers pertain to factors for the organization as a whole. One of the most significant barriers relates to status and power differences. Low-power people may be reluctant to pass bad news up the hierarchy, thus giving the wrong impression to upper levels.82 High-power people may not pay attention or may think that low-status people have little to contribute.

Second, differences across departments in terms of needs and goals interfere with communi- cations. Each department perceives problems in its own terms. The production department is concerned with production efficiency, whereas the marketing department’s goal is to get the product to the customer in a hurry.

Third, the absence of formal channels reduces communication effectiveness. Organizations must provide adequate upward, downward, and horizontal communication in the form of employee surveys, open-door policies, newsletters, memos, task forces, and liaison person- nel. Without these formal channels, the organization cannot communicate as a whole.

Fourth, the communication flow may not fit the team’s or organization’s task. If a central- ized communication structure is used for nonroutine tasks, not enough information will be circulated to solve problems. The organization, department, or team is most efficient when the amount of communication flowing among employees fits the task.

A final problem is poor coordination, so that different parts of the organization are work-ing in isolation without knowing and understanding what other parts are doing. Top executives are out of touch with lower levels, or departments and divisions are so poorly coordinated that people do not understand how the system works together as a whole.

2. OVERCOMING COMMUNICATION BARRIERS

Managers can design the organization to encourage positive, effective communications. Designing involves both individual skills and organizational actions.

Individual Skills. Perhaps the most important individual skill is active listening. Ac- tive listening means asking questions, showing interest, and occasionally paraphrasing what the speaker has said to ensure accurate interpretation. Active listening also means provid- ing feedback to the sender to complete the communication loop.

Second, individuals should select the appropriate channel for the message. A compli- cated message should be sent through a rich channel, such as face-to-face discussion or telephone. Routine messages and data can be sent through memos, let- ters, or e-mail because the risk of misunderstanding is lower.

Third, senders and receivers should make a special effort to understand each other’s perspective. Managers can sensitize themselves to the infor- mation receiver so they can better target the message, detect bias, and clarify misinterpretations. When communicators understand others’ per- spectives, semantics can be clarified, perceptions understood, and objec- tivity maintained.

The fourth individual skill is management by wandering around. Man- agers must be willing to get out of the office and check communications with others. Glenn Tilton, the CEO of United Airlines, takes every op- portunity to introduce himself to employees and customers and find out what’s on their minds. He logs more airplane time than many of his com- pany’s pilots, visits passenger lounges, and chats with employees on con- courses, galleys, and airport terminals.83 Through direct observation and face-to-face meetings, managers like Tilton gain an understanding of the organization and are able to communicate important ideas and values di- rectly to others.

Organizational Actions. Perhaps the most important thing managers can do for the organization is to create a climate of trust and openness. Open communication and dialogue can encourage people to communicate honestly with one another. Subordinates will feel free to transmit negative as well as positive messages without fear of retribution. Efforts to develop interpersonal skills among employees can also foster openness, honesty, and trust.

Second, managers should develop and use formal information channels in all directions. Scandinavian Design uses two newsletters to reach em- ployees. Dana Corporation has developed innovative programs such as the “Here’s a Thought” board-called a HAT rack-to get ideas and feedback from workers. Other techniques include direct mail, bulletin boards, and employee surveys.

Third, managers should encourage the use of multiple channels, includ- ing both formal and informal communications. Multiple communication channels include written directives, face-to-face discussions, MBWA, and the grapevine. For example, managers at GM’s Packard Electric plant use multimedia, including a monthly newspaper, frequent meetings of employee teams, and an electronic news display in the cafeteria. Sending messages through multiple channels increases the likelihood that they will be properly received.

Fourth, the structure should fit communication needs. An organization can be designed to use teams, task forces, project managers, or a matrix structure as needed to facilitate the horizontal flow of information for coordination and problem solving. Structure should also reflect information needs. When team or department tasks are difficult, a decentralized structure should be implemented to encourage discussion and participation.

A system of organizational feedback and learning can help overcome problems of poor coordination. Harrah’s created a Communication Team as part of its structure at the Casino/ Holiday Inn in Las Vegas. The team includes one member from each department. This cross-functional team deals with urgent company problems and helps people think beyond the scope of their own departments to communicate with anyone and everyone to solve those problems.

Source: Daft Richard L., Marcic Dorothy (2009), Understanding Management, South-Western College Pub; 8th edition.

Hello.This post was really remarkable, especially since I was searching for thoughts on this subject last Friday.