The communication model in Exhibit 13.2 illustrates the components of effective communi- cation. Communications can break down if sender and receiver do not encode or decode lan- guage in the same way.9 We all know how difficult it is to communicate with someone who does not speak our language, and today’s managers are often trying to communicate with peo- ple who speak many different native languages. However, communication breakdowns can also occur between people who speak the same language.

Many factors can lead to a breakdown in communications. For example, the selection of communication channel can determine whether the message is distorted by noise and in- terference. The listening skills of both parties and attention to nonverbal behavior can determine whether a message is truly shared. Thus, for managers to be effective communi- cators, they must understand how factors such as communication channels, nonverbal be- havior, and listening all work to enhance or detract from communication.

1. COMMUNICATION CHANNELS

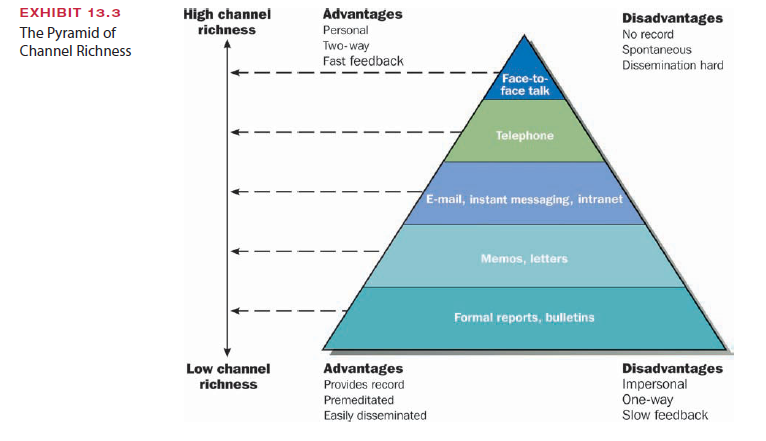

Managers have a choice of many channels through which to communicate to other manag- ers or employees. A manager may discuss a problem face-to-face, make a telephone call, use instant messaging, send an e-mail, write a memo or letter, or put an item in a newslet- ter, depending on the nature of the message. Research has attempted to explain how man- agers select communication channels to enhance communication effectiveness.10 The research has found that channels differ in their capacity to convey information. Just as a pipeline’s physical characteristics limit the kind and amount of liquid that can be pumped through it, a communication channel’s physical characteristics limit the kind and amount of information that can be conveyed through it. The channels available to managers can be classified into a hierarchy based on information richness.

The Hierarchy of Channel Richness. Channel richness is the amount of information that can be transmitted during a communication episode. The hierarchy of channel richness is illustrated in Exhibit 13.3. The capacity of an information channel is influenced by three characteristics: (1) the ability to handle multiple cues simultaneously; (2) the ability to facilitate rapid, two-way feedback; and (3) the ability to establish a per- sonal focus for the communication. Face-to-face discussion is the richest medium because it permits direct experience, multiple information cues, immediate feedback, and personal focus. Face-to-face discussions facilitate the assimilation of broad cues and deep, emotional understanding of the situation. Telephone conversations are next in the richness hierarchy.

Although eye contact, posture, and other body language cues are missing, the human voice can still carry a tremendous amount of emotional information. P. Diddy has learned that face-to-face and direct communication is necessary for business success, as shown in the Benchmarking box.

Electronic messaging, such as e-mail and instant messaging, is increasingly being used for messages that were once handled via the telephone. However, in a survey by researchers at The Ohio State University, most respondents said they preferred the telephone or face- to-face conversation for communicating difficult news, giving advice, or expressing affection.11 Because e-mail messages lack both visual and verbal cues and don’t allow for interaction and feedback, messages can sometimes be misunderstood. Using e-mail to dis- cuss disputes, for example, can lead to an escalation rather than a resolution of conflict.12

Studies have found that e-mail messages tend to be much more blunt than other forms of communication, even other written communications. This bluntness can cause real prob- lems when communicating cross-culturally because some cultures consider directness rude or insulting.13 Instant messaging alleviates the problem of miscommunication to some extent by allowing for immediate feedback.

Instant messaging (IM) allows users to see who is connected to a network and share

short-hand messages or documents with them instantly. A growing number of managers are using IM, indicating that it helps people get responses faster and collaborate more smoothly.14 Overreliance on e-mail and IM can damage company communications because people stop talking to one another in a rich way that builds solid interpersonal relation- ships. However, some research indicates that electronic messaging can enable reasonably rich communication if the technology is used appropriately.15 Organizations are also using interactive meetings over the Internet, sometimes adding video capabilities to provide visual cues and greater channel richness.

Still lower on the hierarchy of channel richness are written letters and memos. Written communication can be personally focused, but it conveys only the cues written on paper and is slower to provide feedback. Impersonal written media, including fliers, bulletins, and standard computer reports, are the lowest in richness. These channels are not focused on a single receiver, use limited information cues, and do not permit feedback.

Selecting the Appropriate Channel. It is important for managers to un- derstand that each communication channel has advantages and disadvantages, and that each can be an effective means of communication in the appropriate circumstances.16

Channel selection depends on whether the message is routine or nonroutine. Nonroutine messages typically are ambiguous, concern novel events, and involve great potential for mis- understanding. They often are characterized by time pressure and surprise. Managers can communicate nonroutine messages effectively by selecting rich channels. Routine messages are simple and straightforward. They convey data or statistics or simply put into words what managers already agree on and understand. Routine messages can be efficiently com- municated through a channel lower in richness, such as e-mail or memorandum. Written communications should also be used when the communication is official, and a permanent record is required.17 E-mail is used so commonly that people often forget to use correct grammar when sending a message for a business reason, as described next.

Consider the alert to consumers issued by the FDA following a widespread e.coli out- break in September 2006. Tainted bagged spinach sickened 199 people in at least 26 states and resulted in one death. Grocers immediately pulled the product from shelves, and wide- spread news coverage warned the public not to consume any bagged spinach until the cause of the contamination could be identified. An immediate response was critical. This type of nonroutine communication forces a rich information exchange. The group will meet face- to-face, brainstorm ideas, and provide rapid feedback to resolve the situation and convey the correct information. If, in contrast, an agency director is preparing a press release about a routine matter such as a policy change or new department members, less information ca- pacity is needed. The director and public relations people might begin developing the press release with an exchange of memos, telephone calls, and e-mail messages.

The key is to select a channel to fit the message. During a major acquisition, one firm decided to send top executives to all major work sites of the acquired company, where most of the workers met the managers in person, heard about their plans for the company, and had a chance to ask questions. The results were well worth the time and expense of the personal face-to-face meetings because the acquired workforce saw their new managers as understanding, open, and willing to listen.18 Communicating their nonroutine message about the acquisition in person prevented damaging rumors and misunderstandings. The choice of a communication channel can also convey a symbolic meaning to the receiver; in a sense, the medium becomes the message. The firm’s decision to communicate face-to- face with the acquired workforce signaled to employees that managers cared about them as individuals.

To persuade and influence, managers have to communicate frequently and easily with others. Yet some people find interpersonal communication experiences unrewarding or difficult and thus tend to avoid situations where communication is required. The term communication apprehension describes this avoidance behavior and is defined as “an individual’s level of fear or anxiety associated with either real or anticipated communica- tion.” With training and practice, managers can overcome their communication apprehen- sion and become more effective communicators.

Effective persuasion doesn’t mean telling people what you want them to do; instead, it involves listening, learning about others’ interests and needs, and leading people to a shared solution.21 Managers who forget that communication means sharing, as described earlier, aren’t likely to be as effective at influencing or persuading others, as the founder and presi- dent of the executive coaching firm Valuedance learned the hard way.

As this example shows, people stop listening to someone when that individual isn’t lis- tening to them. By failing to show interest in and respect for the boss’s point of view, Cramm and her client lost the boss’s interest from the beginning, no matter how suitable the ideas they were presenting. To effectively influence and persuade others, managers have to show they care about how the other person feels. Persuasion requires tapping into people’s emotions, which can only be done on a personal, rather than a rational, impersonal level.

Managers who use symbols, metaphors, and stories to deliver their messages have an easier time influencing and persuading others. Stories draw on people’s imaginations and emotions, which helps managers make sense of a fast-changing environment in ways that people can understand and share. If we think back to our early school years, we may re- member that the most effective lessons often were couched in stories. Presenting hard facts and figures rarely has the same power.

Evidence of the compatibility of stories with human thinking was demonstrated by a study at Stanford Business School.22 The point was to convince MBA students that a company practiced a policy of avoiding layoffs. For some students, only a story was used. For others, statistical data were provided that showed little turnover compared to competitors. For other students, statistics and stories were combined, and yet other students were shown the compa- ny’s official policy statements. Of all these approaches, the students presented with a vivid story alone were most convinced that the company truly practiced a policy of avoiding layoffs. Managers can learn to use elements of storytelling to enhance their communication.23 Stories need not be long, complex, or carefully constructed. A story can be a joke, an analogy, or a verbal snapshot of something from the manager’s own past experiences.24

2. NONVERBAL COMMUNICATION

Managers also use symbols to communicate what is important. Managers are watched, and their behavior, appearance, actions, and attitudes are symbolic of what they value and expect of others.

Most of us have heard the saying that “actions speak louder than words.” Indeed, we communicate without words all the time, whether we realize it or not. Nonverbal communication refers to messages sent through human actions and behaviors rather than through words.25 Most managers are astonished to learn that words themselves carry little meaning. A significant portion of the shared understanding from communica- tion comes from the nonverbal messages of facial expression, voice, mannerisms, posture, and dress.

Nonverbal communication occurs mostly face to face. One researcher found three sources of communication cues during face-to-face communication: the verbal, which are the actual spoken words; the vocal, which include the pitch, tone, and timbre of a person’s voice; and facial expressions. According to this study, the relative weights of these three fac- tors in message interpretation are as follows: verbal impact, 7 percent; vocal impact,

38 percent; and facial impact, 55 percent.26 To some extent, we are all natural face readers, but facial expressions can be misinterpreted, suggesting that managers need to ask questions to make sure they’re getting the right message. Managers can hone their skills at reading facial expressions and improve their ability to connect with and influence followers. Studies indicate that managers who seem responsive to the unspoken emotions of employees are more effective and successful in the workplace.27

This research also strongly implies for managers that “it’s not what you say but how you say it.” Nonverbal messages and body language often convey our real thoughts and feelings with greater force than do our most carefully selected words. Thus, while the conscious mind may be formulating a vocal message such as “Congratulations on your promotion,” body language may be signaling true feelings through blushing, perspiring, or avoiding eye contact. When the verbal and nonverbal messages are contradictory, the receiver will usu- ally give more weight to behavioral actions than to verbal messages.28

A manager’s office sends nonverbal cues as well. For example, what do the following seating arrangements mean? (1) The supervisor stays behind her desk, and you sit in a straight chair on the opposite side. (2) The two of you sit in straight chairs away from her desk, perhaps at a table. (3) The two of you sit in a seating arrangement consisting of a sofa and easy chair. To most people, the first arrangement indicates, “I’m the boss here,” or “I’m in authority.” The second arrangement indicates, “This is serious business.” The third indicates a more casual and friendly, “Let’s get to know each other.”29 Nonverbal messages can be a powerful asset to communication if they complement and support ver- bal messages. Managers should pay close attention to nonverbal behavior when communicating. They can learn to coordinate their verbal and nonverbal messages and at the same time be sensitive to what their peers, subordinates, and supervisors are saying nonverbally.

3. LISTENING

One of the most important tools of manager communication is listening, both to employ- ees and customers. Most managers now recognize that important information flows from the bottom up, not the top down, and managers had better be tuned in.30 This chapter’s “Unlocking Innovative Solutions Through People” box describes how a new managing di- rector and human resources director transformed Kwik-Fit Financial Services by listening to employees who were tired of feeling as though no one in the organization cared about them. Some organizations use innovative techniques for finding out what’s on employees’ and customers’ minds. Cabela’s, a retailer for outdoor enthusiasts, lets employees borrow and use any of the company’s products for a month, as long as they provide feedback that helps other employees better serve customers. The employee fills out a form de- tailing the product’s pros and cons, gives a talk to other employees or customers about the product, and provides feedback in the form of “Item Notes” that are fed into a knowledge-sharing system.31

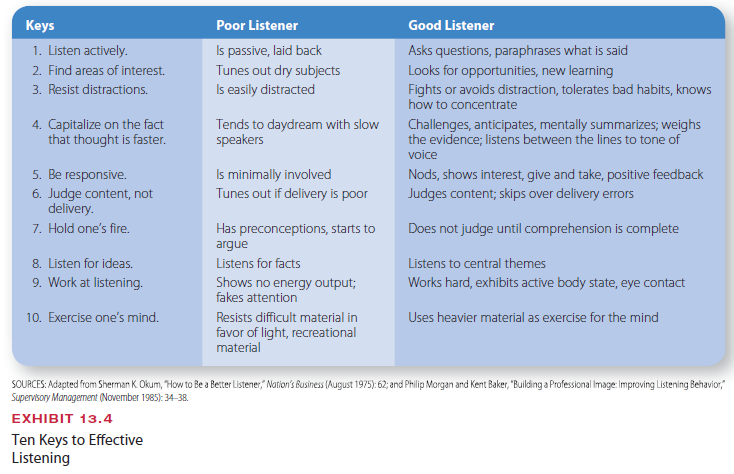

In the communication model in Exhibit 13.2, the lis- tener is responsible for message reception, which is a vital link in the communication process. Listening involves the skill of grasping both facts and feelings to interpret a message’s genuine meaning. Only then can the manager provide the appropriate response. Listening requires at- tention, energy, and skill. Although about 75 percent of effective communication is listening, most people spend only 30 to 40 percent of their time listening, which leads to many communication errors.32 One of the secrets of highly successful salespeople is that they spend 60 to 70 percent of a sales call letting the customer talk.33 How- ever, listening involves much more than just not talking. Many people do not know how to listen effectively. They concentrate on formulating what they are going to say next rather than on what is being said to them. Our lis- tening efficiency, as measured by the amount of material understood and remembered by subjects 48 hours after listening to a 10-minute message, is, on average, no bet- ter than 25 percent.34

What constitutes good listening? Exhibit 13.4 gives 10 keys to effective listening and illustrates a number of ways to distinguish a bad from a good listener. A good listener finds areas of interest, is flexible, works hard at listening, and uses thought speed to mentally summarize, weigh, and anticipate what the speaker says. Good listening means shifting from thinking about self to empathizing with the other person and thus requires a high degree of emo- tional intelligence, as described in Chapter 10. Dr. Robert Buckman, a cancer specialist who teaches other doctors, as well as businesspeople, how to break bad news, emphasizes the importance of listening. “The trust that you build just by letting someone say what they feel is incredible,” Buckman says.35

Few things are as maddening to people as not being listened to. Executives at health- insurer Humana Inc. realized they could grab a bigger share of the Medicare drug benefits business simply by listening to America’s senior citizens.

Source: Daft Richard L., Marcic Dorothy (2009), Understanding Management, South-Western College Pub; 8th edition.

As a Newbie, I am always exploring online for articles that can benefit me. Thank you