1. Managing Productivity

Productivity is significant because it influences the well-being of the entire society as well as of individual companies. The only way to increase the output of goods and services to society is to increase organizational productivity.

1.1. LEAN MANUFACTURING

Many of the concepts we have discussed, including just-in-time inventory and an emphasis on quality, are central to the philosophy of lean manufacturing. Today’s organizations are trying to become more efficient, and implementing the lean manufacturing philosophy is one popular approach to doing so. Lean manufacturing, sometimes called lean produc- tion, uses highly trained employees at every stage of the production process who take a painstaking approach to details and problem solving to cut waste and improve quality and productivity. Lean manufacturing was pioneered by Toyota, and the concept has spread around the world to both manufacturing and service organizations.

The heart of lean manufacturing is not machines or technology but employee involve- ment. Employees are trained to “think lean,” and empowered to make changes to attack waste and strive for continuous improvement in all areas.24 The system combines techniques such as just-in-time inventory, continuous-flow production, quick changeover of assembly lines, continuous improvement, and preventive maintenance with a management system that encourages employee involvement and problem solving. Any employee can stop the production line at any time to solve a problem. In addition, equipment is often designed to stop automatically so that a defect can be fixed.25

1.2. MEASURING PRODUCTIVITY

One important question when considering productivity improvements is: What is produc- tivity, and how do managers measure it? In simple terms, productivity is the organiza- tion’s output of goods and services divided by its inputs. This means that productivity can be improved by either increasing the amount of output using the same level of inputs or re- ducing the number of inputs required to produce the output. Sometimes a company can even do both. Ruggieri & Sons, for example, invested in mapping software to help it plan deliveries of heating fuel. The software plans the most efficient routes based on the loca- tions of customers and fuel reloading terminals, as well as the amount of fuel each customer needs. When Ruggieri switched from planning routes by hand to using the software, its drivers began driving fewer miles but making 7 percent more stops each day—in others words, burning less fuel to sell more fuel.26

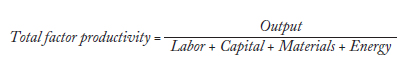

The accurate measure of productivity can be complex. Two approaches for measuring productivity are total factor productivity and partial productivity. Total factor produc- tivity is the ratio of total outputs to the inputs from labor, capital, materials, and energy:

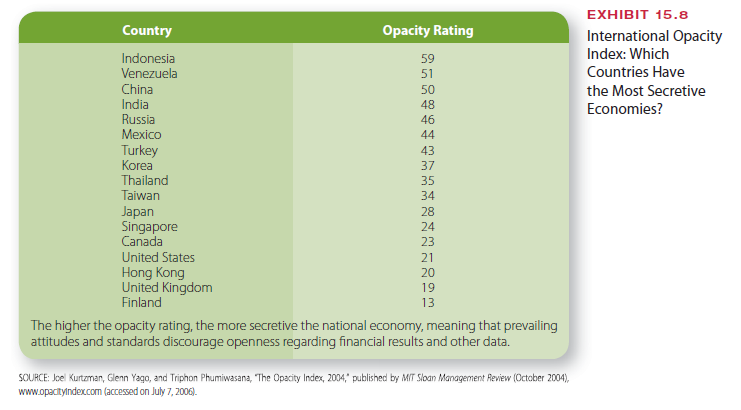

Total factor productivity represents the best measure of how the organization is doing. Often, however, man- agers need to know about productivity with respect to certain inputs. Partial productivity is the ratio of total outputs to a major category of inputs. For example, many organizations are interested in labor productivity, which is measured as follows:

Calculating this formula for labor, capital, or materials provides information on whether improvements in each element are occurring. However, managers often are crit- icized for relying too heavily on partial productivity mea- sures, especially direct labor.27 Measuring direct labor misses the valuable improvements in materials, work pro- cesses, and quality. Labor productivity is easily measured but may show an increase as a result of capital improve- ments. Thus, managers will misinterpret the reason for productivity increases.

2. Total Quality Management (TQM)

One popular approach based on a decentralized control philosophy is total quality man- agement (TQM), an organization-wide effort to infuse quality into every activity in a company through continuous improvement. Managing quality is a concern for every orga- nization. The Yugo was the lowest-priced car on the market when it was introduced in the United States in 1985, yet four years later, the division went bankrupt, largely as a result of quality problems in both products and services.28 In contrast, Toyota has steadily gained market share over the past several decades and will likely soon overtake General Motors as the world’s top-selling auto maker.29 The difference comes down to quality. Toyota is a model of what happens when a company makes a strong commitment to TQM.

TQM became attractive to U.S. managers in the 1980s because it had been successfully implemented by Japanese companies, such as Toyota, Canon, and Honda, which were gain- ing market share and an international reputation for high quality. The Japanese system was based on the work of such U.S. researchers and consultants as Deming, Juran, and Feigenbaum, whose ideas attracted U.S. executives after the methods were tested overseas.30

The TQM philosophy focuses on using teamwork, increasing customer satisfaction, and lowering costs. Organizations implement TQM by encouraging managers and employees to collaborate across functions and departments, as well as with customers and suppliers, to identify areas for improvement, no matter how small. Each quality improvement is a step toward perfection and meeting a goal of zero defects. Quality control becomes part of the day- to-day business of every employee, rather than being assigned to specialized departments.

The implementation of TQM is similar to that of other decentralized control methods. Feedforward controls include training employees to think in terms of prevention, not de- tection, of problems and giving them the responsibility and power to correct errors, expose problems, and contribute to solutions. Concurrent controls include an organizational cul- ture and employee commitment that favor total quality and employee participation. Feed- back controls include targets for employee involvement and for zero defects.

2.1. TQM TECHNIQUES

The implementation of TQM involves the use of many techniques, including quality circles, benchmarking, Six Sigma principles, reduced cycle time, and continuous improvement.

Quality Circles. One technique for implementing the decentralized approach of TQM is to use quality circles. A quality circle is a group of 6 to 12 volunteer employees who meet regularly to discuss and solve problems affecting the quality of their work.31 At a set time during the workweek, the members of the quality circle meet, identify problems, and try to find solutions. Circle members are free to collect data and take surveys. Many companies train people in team building, problem solving, and statistical quality control. The reason for using quality circles is to push decision making to an organization level at which recommen- dations can be made by the people who do the job and know it better than anyone else.

Benchmarking. Introduced by Xerox in 1979, benchmarking is now a major TQM component. Benchmarking is defined as “the continuous process of measuring products, services, and practices against the toughest competitors or those companies recognized as industry leaders to identify areas for improvement.”32 The key to successful benchmarking lies in analysis. Starting with its own mission statement, a company should honestly ana- lyze its current procedures and determine areas for improvement. As a second step, a com- pany carefully selects competitors worthy of copying. For example, Xerox studied the order fulfillment techniques of L.L.Bean, the Freeport, Maine, mail-order firm, and learned ways to reduce warehouse costs by 10 percent. Companies can emulate internal processes and procedures of competitors but must take care to select companies whose methods are disciplined and relentless pursuit of higher quality and lower costs. The discipline is based on a five-step methodology referred to as DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, and Control, pronounced “de-May-ick” for short), which provides a structured way for organi- zations to approach and solve problems.34 GE bought a Hollywood studio and is trying to implement a form of Six Sigma, as shown in the Benchmarking box.

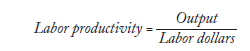

Effectively implementing Six Sigma requires a major commitment from top manage- ment because Six Sigma involves widespread change throughout the organization. Hun- dreds of organizations have adopted some form of Six Sigma program in recent years. Highly committed companies, including ITT Industries, Motorola, General Electric, Allied Signal, ABB Ltd., and DuPont & Co., send managers to weeks of training to become qualified as Six Sigma “black belts.” These black belts lead projects aimed at improving targeted areas of the business.35 Although originally applied to manufacturing, Six Sigma has evolved to a process used in all industries and affecting every aspect of company operations, from human resources to customer service. Exhibit 15.6 lists some statistics that illustrate why Six Sigma is important for both manufacturing and service organizations. Cox Communications, Inc., based in Atlanta, Georgia, used Six Sigma to improve the “time to answer” metric for the company’s help desk. According to Tom Guthrie, vice president of operations, the process enabled Cox to reduce staffing by 20 percent, saving big bucks, while also cutting the aban- don rate (the number of calls abandoned before being answered) by 40 percent.36

Reduced Cycle Time. Cycle time has become a critical quality issue in today’s fast-paced world. Cycle time refers to the steps taken to complete a company process, such as teaching a class, publishing a textbook, or designing a new car. The simplification of work cycles, including dropping barriers between work steps and among departments and remov- ing worthless steps in the process, enables a TQM program to succeed. Even if an organiza- tion decides not to use quality circles or other techniques, substantial improvement is possi- ble by focusing on improved responsiveness and acceleration of activities into a shorter time. Reduction in cycle time improves overall company performance as well as quality.37

L.L.Bean is a recognized leader in cycle time control. Workers used flowcharts to track their movements, pinpoint wasted motions, and completely redesign the order-fulfillment process. Today, a computerized system breaks down an order based on the geographic area of the warehouse in which items are stored. Items are placed on conveyor belts, where elec- tronic sensors re-sort the items for individual orders. After orders are packed, they are sent to a FedEx facility on site. Improvements such as these have enabled L.L.Bean to process most orders within two hours after the order is received.38

Continuous Improvement. In North America, crash programs and designs have traditionally been the preferred method of innovation. Managers measure the expected bene- fits of a change and favor the ideas with the biggest payoffs. In contrast, Japanese companies have realized extraordinary success from making a series of mostly small improvements. This approach, called continuous improvement, or kaizen, is the implementation of a large number of small, incremental improvements in all areas of the organization on an ongoing basis. In a successful TQM program, all employees learn that they are expected to contribute by initiating changes in their own job activities. The basic philosophy is that improving things a little bit at a time, all the time, has the highest probability of success. Innovations can start simple, and employees can build on their success in this unending process.

2.2. TQM SUCCESS FACTORS

Despite its promise, TQM does not always work. A few firms have had disappointing results. In particular, Six Sigma principles might not be appropri- ate for all organizational problems, and some companies have expended tremen- dous energy and resources for little payoff.39 Many contingency factors (listed in Exhibit 15.7) can influence the success of a TQM program. For example, quality circles are most beneficial when employees have chal- lenging jobs; participation in a quality circle can contribute to productivity because it enables employees to pool their knowledge and solve interesting problems. TQM also tends to be most successful when it enriches jobs and improves employee motivation. In addition, when participating in the quality program improves workers’ problem-solving skills, productivity is likely to increase. Finally, a quality program has the greatest chance of success in a corporate culture that values quality and stresses continuous improvement as a way of life.

3. Trends in Quality Control

Many companies are responding to changing economic realities and global competition by reassessing organizational management and processes—including control mechanisms. Some of the major trends in quality and financial control include international quality standards and economic value-added and market value-added systems.

3.1. INTERNATIONAL QUALITY STANDARDS

One impetus for TQM in the United States is the increasing significance of the global economy. Many countries have adopted a universal benchmark for quality assurance, ISO certification, which is based on a set of international standards for quality established by the International Standards Organization in Geneva, Switzerland.40 Hundreds of thou- sands of organizations in 150 countries, including the United States, have been certified to demonstrate their commitment to quality. Europe continues to lead in the total number of certifications, but the greatest number of new certifications in recent years has been in the United States. One of the more interesting organizations to recently become ISO certified was the Phoenix, Arizona, Police Department’s Records and Information Bureau. In today’s environment, where the credibility of law enforcement agencies has been called into question, the Bureau wanted to make a clear statement about its commitment to quality and accuracy of information provided to law enforcement personnel and the public.41

ISO certification has become the recognized standard for evaluating and comparing com-panies on a global basis, and more U.S. companies are feeling the pressure to participate to remain competitive in international markets. In addition, many countries and companies require ISO certification before they will do business with an organization.

Economic Value-Added (EVA). Hundreds of companies, including AT&T, Quaker Oats, the Coca-Cola Company, and Philips Petroleum Company, have set up economic value-added (EVA) measurement systems as a new way to gauge financial performance. EVA can be defined as a company’s net (after-tax) operating profit minus the cost of capital invested in the company’s tangible assets.42 Measuring performance in terms of EVA is intended to capture all the things a company can do to add value from its activi- ties, such as run the business more efficiently, satisfy customers, and reward shareholders. Each job, department, process, or project in the organization is measured by the value added. EVA can also help managers make more cost-effective decisions. At Boise Cascade, the vice president of IT used EVA to measure the cost of replacing the company’s existing storage devices against keeping the existing storage assets that had higher maintenance costs. Using EVA demonstrated that buying new storage devices would lower annual maintenance costs significantly and easily make up for the capital expenditure.43

3. Innovative Control Systems for Turbulent Times

As we have discussed throughout this text, globalization, increased competition, rapid change, and uncertainty have resulted in new organizational structures and management methods that emphasize information sharing, employee participation, learning, and teamwork. These shifts have, in turn, led to some new approaches to control. Two additional aspects of control in today’s organizations are open-book management and use of the balanced scorecard.

3.1. OPEN-BOOK MANAGEMENT

In an organizational environment that promotes information sharing, teamwork, and the role of managers as facilitators, executives cannot hoard information and financial data. They admit employees throughout the organization into the loop of financial control and responsibility to encourage active participation and commitment to goals. A growing num- ber of managers are opting for full disclosure in the form of open-book management. Open-book management allows employees to see for themselves—through charts, computer printouts, meetings, and so forth—the financial condition of the company. Sec- ond, open-book management shows the individual employee how his or her job fits into the big picture and affects the financial future of the organization. Finally, open-book management ties employee rewards to the company’s overall success. With training in in- terpreting the financial data, employees can see the interdependence and importance of each function. If they are rewarded according to performance, they become motivated to take responsibility for their entire team or function, rather than merely their individual jobs.44 Cross-functional communication and cooperation are also enhanced.

The goal of open-book management is to get every employee thinking and acting like a business owner. To get employees to think like owners, management provides them with the same information owners have: what money is coming in and where it is going. Open- book management helps employees appreciate why efficiency is important to the organiza- tion’s success as well as their own. Open-book management turns traditional control on its head. Development Counsellors International, a New York City public relations firm, found an innovative way to involve employees in the financial aspects of the organization.

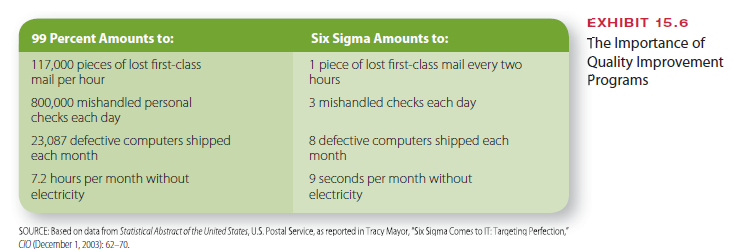

Managers in some countries have more trouble running an open-book company because prevailing attitudes and standards encourage confidentiality and even secrecy concerning financial results. Many businesspeople in countries such as China, Russia, and Indonesia, for example, are not accustomed to publicly disclosing financial details, which can present prob- lems for multinational companies operating there.47 Exhibit 15.8 lists a portion of a recent Opacity Index, which offers some indication of the degree to which various countries are open regarding economic matters. The higher the rating, the more opaque, or hidden, the economy of that country. In the partial index in Exhibit 15.8, Indonesia has the highest opacity rating at 59, and Finland the lowest at 13. The United States has an opacity rating of 21, which is fairly low on the index of countries. In countries with higher ratings, financial figures are typically closely guarded and managers may be discouraged from sharing information with employees and the public. Globalization is beginning to have an impact on economic opacity in various countries by encouraging a convergence toward global accounting standards that support more accurate collection, recording, and reporting of financial information.

3.2. THE BALANCED SCORECARD

Another recent innovation is to integrate the various dimensions of control, combining internal financial measurements and statistical reports with a concern for markets and customers as well as employees.48 Whereas many managers once focused primarily on mea- suring and controlling financial performance, they are increasingly recognizing the need to measure other, intangible aspects of performance to assess the value-creating activities of the contemporary organization.49 Many of today’s companies compete primarily on the basis of ideas and relationships, which requires that managers find ways to measure intan- gible as well as tangible assets.

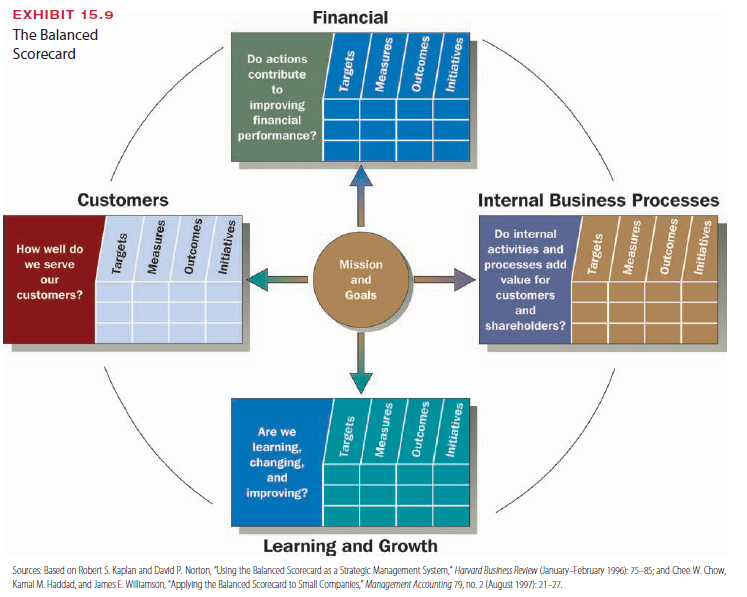

One fresh approach is the balanced scorecard. The balanced scorecard is a comprehensive management control system that balances traditional financial measures with operational mea- sures relating to a company’s critical success factors.50 A balanced scorecard contains four major perspectives, as illustrated in Exhibit 15.9: financial performance, customer service, internal business processes, and the organization’s capacity for learning and growth.51 Within these four areas, managers identify key performance metrics that the organization will track. The financial performance perspective reflects a concern that the organization’s activities contribute to improv- ing short- and long-term financial performance. It includes traditional measures such as net income and return on investment. Customer service indicators measure such things as how customers view the organization, as well as customer retention and satisfaction. Business process indicators focus on production and operating statistics, such as order fulfillment or cost per order. The final component looks at the organization’s potential for learning and growth, focusing on how well resources and human capital are being managed for the company’s future. Metrics may include such things as employee retention and the introduction of new products. The compo- nents of the scorecard are designed in an integrative manner, as illustrated in Exhibit 15.9.

Managers record, analyze, and discuss these various metrics to determine how well the organization is achieving its strategic goals. The balanced scorecard is an effective tool for managing and improving performance only if it is clearly linked to a well-defined organiza- tional strategy and goals.52 At its best, use of the scorecard cascades down from the top levels of the organization, so that everyone becomes involved in thinking about and discussing strategy.53 The scorecard has become the core management control system for many organi- zations, including well-known organizations such as Bell Emergis (a division of Bell Canada), ExxonMobil, Cigna Insurance, British Airways, Hilton Hotels Corp., and even some units of the U.S. federal government.54 British Airways clearly ties its use of the bal- anced scorecard to the feedback control model we discussed early in this chapter. Scorecards are used as the agenda for monthly management meetings. Managers focus on the various elements of the scorecard to set targets, evaluate performance, and guide discussion about what further actions need to be taken.55 As with all management systems, the balanced scorecard is not right for every organization in every situation. The simplicity of the system causes some managers to underestimate the time and commitment that is needed for the approach to become a truly useful management control system. If managers implement the balanced scorecard using a performance measurement orientation rather than a performance management approach that links targets and measurements to corporate strategy, use of the scorecard can actually hinder or even decrease organizational performance.56

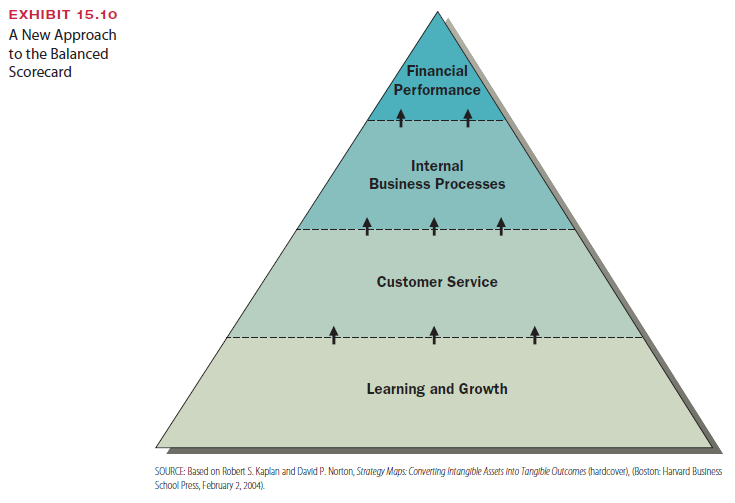

In addition, the scorecard has evolved from a system that places equal emphasis on the four categories of performance management illustrated in Exhibit 15.9 into a cause-effect relation- ship that calls attention to how organizations achieve higher performance. This adapted approach to the scorecard, illustrated in Exhibit 15.10, indicates that financial results are the final outcome of other processes within the company. The foundation of high financial perfor- mance is learning and growth, which reflects that it is an organization’s people and culture that cause excellent business processes. Excellent business processes in turn cause customers to be satisfied. And happy customers lead to financial success. Thus, the components of the scorecard can be organized into a pyramid, indicating that each level shown in Exhibit 15.10 reinforces the level above it. Thus, high financial performance is an outgrowth of success in other areas, starting with a firm commitment to developing human capital and internal business processes.

3.3. NEW WORKPLACE CONCERNS

Managers in today’s organizations face some difficult control issues. The matter of control has come to the forefront in light of the failure of top executives and corporate directors to provide adequate oversight and control at companies such as Enron, HealthSouth, Adelphia, and WorldCom. Thus, many organizations are moving toward increased con- trol, particularly in terms of corporate governance, which refers to the system of govern- ing an organization so that the interests of corporate owners are protected. The financial reporting systems and the roles of boards of directors are being scrutinized in organizations around the world. At the same time, top leaders are also keeping a closer eye on the activi- ties of lower-level managers and employees.

In a fast-moving environment, undercontrol can be a problem because managers can’t keep personal tabs on everything in a large, global organization. Consider, for example, that many of the CEOs who have been indicted in connection with financial misdeeds have claimed that they were unaware that the misconduct was going on. In some cases, these claims might be true, but they reflect a significant breakdown in control. In response, the U.S. government enacted the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, often referred to as SOX, which requires several types of reforms, including better internal monitoring to reduce the risk of fraud, certification of financial reports by top leaders; improved measures for exter- nal auditing; and enhanced public financial disclosure. SOX has been unpopular with many business leaders, largely because of the expense of complying with the act. In addition, some critics argue that SOX is creating a culture of overcontrol that is stifling innovation and growth. Even among those who agree that government regulation is needed, calls for a more balanced regulatory scheme that requires transparency and objectivity without re- straining innovation are growing.57

Overcontrol of employees can be damaging to an organization as well. Managers might feel justified in monitoring e-mail and Internet use, as described earlier in the Spotlight feature, for example, to ensure that employees are directing their behavior toward work rather than personal outcomes, and to alleviate concerns about potential racial or sexual harassment. Yet employees often resent and feel demeaned by close monitoring that limits their personal freedom and makes them feel as if they are constantly being watched. Exces- sive control of employees can lead to demotivation, low morale, lack of trust, and even hos- tility among workers. Managers have to find an appropriate balance, as well as develop and communicate clear policies regarding workplace monitoring. Although oversight and con- trol are important, good organizations also depend on mutual trust and respect among managers and employees.

Source: Daft Richard L., Marcic Dorothy (2009), Understanding Management, South-Western College Pub; 8th edition.

Great work! This is the type of info that are meant to be shared around the

net. Disgrace on Google for not positioning this

post higher! Come on over and visit my site .

Thanks =)