Let us first illustrate a case in which two or more factors have a combined influence but are experimented with one factor at a time.

Example 7.1

We call our experimenter here “coffee lover.” He guessed that “great” coffee is the result of adding to the fresh brew of a given strength of a given brand of coffee the right quantity of cream and the right quantity of sugar, then drinking it at the right temperature. But, to his disappointment, the experience of “great” coffee did not happen every day. On those rare days that it happened, he secretly said to himself, “Today is my lucky day.” Inclined to be scientific, one day he decides to find the right combination and be done with the luck business. After considerable reflection on his coffee taste, he decides to vary the cream between 0.5 and 2.5 teaspoons in steps of 0.5 teaspoons; to vary the sugar between 0.5 and 2.5 teaspoons in steps of 0.5 teaspoons; and to start drinking after 0.5 and 2.5 minutes in steps of 0.5 minutes, after preparing the cup of coffee, steaming hot.

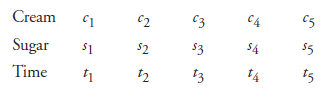

He symbolized the order of increasing quantities of the variables as below:

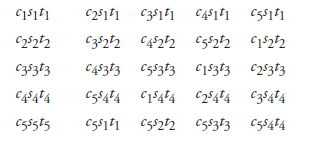

Further he writes down the following combinations:

He sets to work methodically to drink one cup of coffee at the same hour on consecutive days for each of the above combinations. During this period, of over three weeks, he often has to gulp some pretty bad stuff because those were not the right combinations for his taste. Only on a few days does he find the taste to be somewhat like, but not exactly, the right taste he knows. He is beginning to feel the fatigue of the experiment. At the end of those twenty-five days, still unsatisfied, he takes a second look at the experimental schedule he prepared and followed through.

He notices the following:

- There are a lot more possible combinations than his table included.

- The first line of his table gives the effect of varying c, but does so with s, and t, both at the lowest levels only. Even if he finds the best level for c, it is possible, indeed more than likely, that the levels S1 and t1 are not the best.

- The second line also gives the effect of variation for c, but again is tied with only one level each of s and t, creating the same doubt as before.

- The first column of the table, and partly the other columns also, show the effect of varying c, but mixed up with different s-t He had wanted to keep the s-t combination constant. The levels are S2t2, s^t5, and so forth, always incrementing together. Where is, for example, a combination like s2t4 or s3t5?

- Where is a column or a line that shows the effect of varying s only, keeping the c-t combination constant?

Our coffee lover is now fatigued, confused, and frustrated. He fears that with all these goings on, he may develop an aversion for coffee; that would be a terrible thing to have happen. Not committed to secrecy in experimenting, he explains the situation to a friend, who happens to be a math teacher. After a few minutes of juggling figures, the teacher tells him that there are one hundred more possible combinations that he could add to his table of experiments. Noticing disappointment written large on his friend’s face, the teacher tells him that this experiment format, to be called one factor at a time, is not the best way to go and offers to help him devise a shorter and more fruitful program if and when his friend is ready. The coffee lover takes a rain check, having decided that coffee is for enjoying, not for experimenting—at least for now. Having witnessed the frustration of the one-factor- at-a-time experiment, we may now illustrate a simple case of factorial design.

Source: Srinagesh K (2005), The Principles of Experimental Research, Butterworth-Heinemann; 1st edition.

4 Aug 2021

5 Aug 2021

5 Aug 2021

4 Aug 2021

5 Aug 2021

4 Aug 2021