Managing individual performance in organisations has traditionally centred on assessing performance and allocating reward, with effective performance seen as the result of the interaction between individual ability and motivation.

Increasingly, it is recognised that planning and enabling performance have a critical effect on individual performance, with performance goals and standards, appropriate resources, guidance and support from the individual’s manager all being central.

The words ‘performance management’ are sometimes used to imply organisational targets, frameworks like the balanced scorecard, measurements and metrics, with individual measures derived from these. This meaning of performance management has been described by Houldsworth (2004) as a harder ‘performance improvement’ approach compared with the softer developmental and motivational approaches to aligning the individual and the organisation, which she suggests equates to good management practice. We adopt this as a very helpful distinction and in this chapter focus on the softer approach to employees and teams, covering aspects of the organisational measurement approach in Chapter 33 on Information technology and human capital measurement.

1. PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT AND PERFORMANCE APPRAISAL

1.1. Appraisal systems

Traditionally performance appraisal systems have provided a formalised process to review employee performance. They are centrally designed, usually by the HR function, requiring each line manager to appraise the performance of their staff, usually each year. This normally requires the manager and employee to take part in a performance review meeting. Elaborate forms are often completed as a record of the process, but these are not living documents, they are generally stored in the archives of the HR department, and the issue of performance is often neglected until the next round of performance review meetings.

What is being appraised varies and might cover personality, behaviour or job performance, with measures being either quantitive or qualitative. Qualitative appraisal is often an unstructured narrative on the general performance of the appraisee, although some guidance might be given as to the areas on which the appraiser should comment. The problem with qualitative appraisals is that they may leave important areas unappraised, and that they are not suitable for comparison purposes.

Coates (1994) argues that what is actually measured in performance appraisal is the extent to which the individual conforms to the organisation. Some traditional appraisal was based on measures of personality traits that were felt to be important to the job. These included traits such as resourcefulness, enthusiasm, drive, application and other traits such as intelligence. One difficulty with these is that everyone defines them differently. Raters, therefore, are often unsure of what they are rating, leaving more scope for bias and prejudice. Another problem is that since the same scales are often used for many different jobs, traits that are irrelevant to an appraisee’s job may still be measured.

Other approaches link ratings to behaviour and performance on the job. So performance may be reviewed against key aspects of the job or major headings on the job description. Behaviourally anchored rating scales (BARS) and behavioural observation scales (BOS) are specific methods of linking ratings with behaviour at work, although evidence suggests that these are not widely used (Williams 2002).

Another method of making appraisal more objective is to use the process to set job objectives over the coming year and, a year later, to measure the extent to which these objectives have been met. The extent to which the appraisee is involved in setting these objectives varies considerably. When a competency profile has been identified for a particular job, it is then possible to use this in the appraisal of performance. Many appraisal systems combine competency assessment with assessment against objectives or job accountabilities. IRS (2005b) report that 89 per cent of their respondents that used appraisals measured employees against objectives or goals, with 56 per cent measuring against competencies and 53 per cent measuring against pre-set performance standards, as might be used in a harder approach to performance improvement.

Lastly, performance may be appraised by collecting primary data via various forms of electronic surveillance system. There are increasing examples of how activity rates of computer operators can be recorded and analysed, and how the calls made by telephone sales staff can be overheard and analysed. Sewell and Wilkinson (1992) describe a Japanese electronics plant where the final electronic test on a piece of equipment can indicate not only faults but the individual operator responsible for them. On another level some companies test the performance of their sales staff by sending in assessors acting in the role of customer (Newton and Findlay 1996), often termed ‘mystery shoppers’.

In a recent survey (IRS 2005a) 146 of the 154 respondents used appraisal, and of the 146 mixed size, but mainly large companies, 91 per cent appraised all employees. But while performance appraisal has gradually been applied to wider groups of employees, beyond managers and professionals, there are also concerns that appraisal systems are treated as an administrative exercise, are ineffective, and do little to improve performance of employees in the future.

A further problem with such systems is the lack of clarity of purpose. The Employment Studies Institute (IRS 2001) suggests that appraisal is a victim of its own expectations, in that it is expected to deliver in too many areas. Systems may focus on development, identifying future potential, reward, identifying poor performers, or motivation. In systems where appraisal results were linked to reward the manager was placed in the position of an assessor or judge. Alternatively some systems focused on support or development, particularly in the public sector. These provided a better opportunity for managers to give constructive feedback, for employees to be open about difficulties, and for planning to improve future performance. Many systems try to encompass both approaches; for example in the IRS survey (IRS 2005b) 92 per cent of companies used appraisal to determine training and development needs (mainly formally), and 65 per cent used the system either formally or informally to determine pay, with 43 per cent using it formally or informally to determine bonuses. However, as these approaches conflict, the results are typically unsatisfactory.

Another example is an event experienced by one of the present authors when running a course on Performance Appraisal in the Czech Republic some time after the Velvet Revolution. Managers on the course said that the use of performance appraisal would be entirely unacceptable at that time as workers would associate it with what had gone before under the communist regime. Apparently every year a list of workers was published in order of the highest to the lowest performer. Whilst this list was claimed to represent work performance the managers said that in reality it represented degrees of allegiance to the communist party and was nothing to do with work performance.

The effectiveness of appraisal systems hinges on a range of different factors. Research by Longenecker (1997) in the USA sheds some light on this. In a large-scale survey and focus groups he found that the three most common reasons for failure of an appraisal system were: unclear performance criteria or an ineffective rating instrument (83 per cent); poor working relationships with the boss (79 per cent); and that the appraiser lacked information on the manager’s actual performance (75 per cent). Other problems were a lack of ongoing performance feedback (67 per cent) and a lack of focus on management development/improvement (50 per cent). Smaller numbers identified problems with the process, such as lack of appraisal skills (33 per cent) and the review process lacking structure or substance (29 per cent).

Ownership of the system is also important. If it is designed and imposed by the HR function there may be little ownership of the system by line managers. Similarly, if paperwork has to be returned to the HR function it may well be seen as a form-filling exercise for someone else’s benefit and with no practical value to performance within the job. There is an increasing literature indicating that appraisal can have serious negative consequences for the employee and IRS (2005b) found that whilst 40 per cent of respondents in their survey reported no negative consequences, 30 per cent had negative impacts for the organisation, the individual or a relationship, and were able to explain specific incidents where this had happened. Political manipulation of the appraisal process is increasingly being recognised as problematic.

More fundamentally Egan (1995) argues that the problem with appraisal not only relates to poor design or implementation, but is rooted deeply in the basic reaction of organisational members to such a concept. There is an increasing body of critical literature addressing the role and theory of appraisal. These debates centre on the underlying reasons for appraisal (see, for example, Barlow 1989; Townley 1989, 1993; Newton and Findlay 1996) and the social construction of appraisal (see, for example, Grint 1993). This literature throws some light on the use and effectiveness of performance appraisal in organisations.

1.2. Performance management systems

While many appraisal systems are still in existence and continue to be updated, performance management systems are increasingly seen as the way to manage employee performance, and have incorporated the appraisal/review process into this. In the Focus on skills at the end of Part 3 we consider the performance appraisal interview in the context of either an appraisal or a performance management system. Clark (2005) provides a useful definition of performance management, stating that the essence of it is:

Establishing a framework in which performance by human resources can be directed, monitored, motivated and refined, and that the links in the cycle can be audited. (p. 318)

Bevan and Thompson (1992) found that 20 per cent of the organisations they surveyed had introduced a performance management system. Armstrong and Baron (1998a) report that 69 per cent of the organisations they surveyed in 1997 operated a formal process to measure manager performance. Such systems are closely tied into the objectives of the organisation, so that the resulting performance is more likely to meet organisational needs. The systems also represent a more holistic view of performance. Performance appraisal or review is almost always a key part of the system, but is integrated with performance planning, which links an individual’s objectives to business objectives to

ensure that employee effort is directed towards organisational priorities: support for performance delivery (via development plans, coaching and ongoing review) to enable employee effort to be successful, and that performance is assessed and successful performance rewarded and reinforced.

The conceptual foundation of performance management relies on a view that performance is more than ability and motivation. It is argued that clarity of goals is key in enabling the employee to understand what is expected and the order of priorities. In addition goals themselves are seen to provide motivation, and this is based on goalsetting theory originally developed by Locke in 1968 and further developed with practical applicability (Locke and Latham 1990). Research to date suggests that for goals to be motivating they must be sufficiently specific, challenging but not impossible and set participatively. Also the person appraised needs feedback on future progress.

The other theoretical base of performance management is expectancy theory, which states that individuals will be motivated to act provided they expect to be able to achieve the goals set, believe that achieving the goals will lead to other rewards and believe that the rewards on offer are valued (Vroom 1964). Given such an emphasis on a link into the organisation’s objectives it is somewhat disappointing that Bevan and Thompson found no correlation between the existence of a performance management system and organisational performance in the private sector. Similarly, Armstrong and Baron (1998a) report from their survey that no such correlation was found. They do report, however, that 77 per cent of organisations surveyed regarded their systems as effective to some degree and Houldsworth (2003), using the Henley and Hay Group survey of top FTSE companies and public sector respondents, reports that 68 per cent of organisations rated their performance management effectiveness as excellent. While Houldsworth et al. (2005) propose that performance management practice is now more sophisticated and better received by employees, we suggest that it still remains an act of faith.

Some performance management systems are development driven and some are reward driven. Whereas in the 1992 IPD survey 85 per cent of organisations claimed to link performance management to pay (Bevan and Thompson 1992), Armstrong and Baron (1998a) found that only 43 per cent of survey respondents reported such a link. However, 82 per cent of the organisations visited had some form of performance-related pay (PRP) or competency-based pay, so the picture is a little confusing. They suggest that a view is emerging of performance management which centres on ‘dialogue’, ‘shared understanding’, ‘agreement’ and ‘mutual commitment’, rather than rating for pay purposes. To this end organisations are increasingly suggesting that employees take more ownership of performance management (see Scott 2006 for a good example) and become involved in collecting self-assessment evidence throughout the year (IDS 2005). While these characteristics may feature in more sophisticated systems, Houldsworth (2003) reports that 77 per cent of organisations link performance assessments with pay, and it appears that many organisations are trying to achieve both development and reward outcomes. She also contrasts systems driven by either performance development or performance measurement, finding that the real experience of developmental performance management is that it is motivational, encourages time spent with the line manager, encourages two-way communication and is an opportunity to align roles and training with business needs. Alternatively, where there is a measurement focus, performance management is seen as judgemental, a chance to assess and get rid of employees, emphasises control and getting more out of staff, raises false expectations and is a way to manage the salaries bill. (See Table 13.1.)

2. STAGES IN A PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT SYSTEM

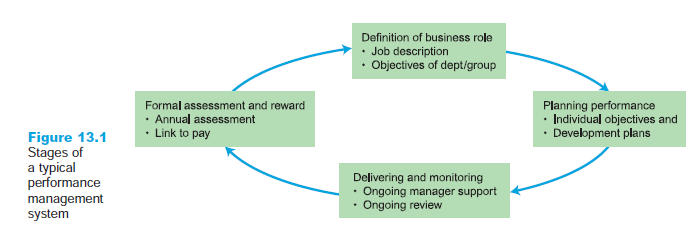

Figure 13.1 shows a typical performance management system, including both development and reward aspects, the main stages of which are discussed below.

2.1. Business mission, values, objectives and competencies

There is an assumption that before it is able to plan and manage individual performance the organisation will have made significant steps in identifying the performance required of the organisation as a whole. In most cases this will involve a mission statement so that performance is seen within the context of an overriding theme. In addition many organisations will identify the strategic business objectives that are required within the current business context to be competitive and that align with the organisation’s mission statement.

Many organisations will also identify core values of the business and the key competencies required. Each of these has a potential role in managing individual performance.

Organisational objectives are particularly important, as it is common for such objectives to be cascaded down the organisation in order to ensure that individual objectives contribute to their achievement (for an example of an objective-setting cascade, see Figure 13.2).

2.2. Planning performance: a shared view of expected performance

Individual objectives derived from team objectives and an agreed job description can be jointly devised by manager and employee. These objectives are outcome/results oriented rather than task oriented, are tightly defined and include measures to be assessed. The objectives are designed to stretch the individual, and offer potential development as well as meeting business needs. It is helpful to both the organisation and the individual if objectives are prioritised. Many organisations use the ‘SMART’ acronym for describing individual objectives or targets:

- Specific

- Measurable

- Appropriate

- Relevant

- Timed

It is clearly easier for some parts of the organisation than others to set targets. There is often a tendency for those in technical jobs, such as computer systems development, to identify purely technical targets, reflecting the heavy task emphasis they see in their jobs. Moving staff to a different view of how their personal objectives contribute to team and organisational objectives is an important part of the performance management process. An objective for a team leader in systems development could be:

To complete development interviews with all team members by end July 2007 (written March 2007).

Clearly, the timescale for each objective will need to reflect the content of the objective and not timescales set into the performance management system. As objectives are met, managers and their staff need to have a brief review meeting to look at progress in all objectives and decide what other objectives should be added, changed or deleted. Five or six ongoing objectives are generally sufficient for one individual to work on at any time. A mix of objectives about new developments and changes as well as routine aspects of the job is generally considered to be appropriate.

The critical point about a shared view of performance suggests that handing out a job description or list of objectives to the employee is not adequate. Performance expectations need to be understood and, where possible, to involve a contribution from the employee. For example, although key accountabilities may be fixed by the manager, they will need to be discussed. Specific objectives allow for and benefit from a greater degree of employee input as employees will have a valid view of barriers to overcome, the effort involved and feasibility. Expressing objectives as a ‘what’ statement rather than a ‘how’ statement gives employees the power to decide the appropriate approach once they begin to work on the issue. Incorporating employee input and using ‘what’ statements are likely to generate a higher degree of employee ownership and commitment. However, difficulties have been experienced with purely ‘what’ objectives as there may be appropriate and inappropriate ways of achieving an objective. For example, a manager with an objective to ensure that another department agrees to a plan of action could achieve this in different ways. The manager may pressure susceptible members of the other department and force agreement through without listening to the other department’s perspective. This may alienate the other department and damage future good relations. Alternatively the manager could adopt a collaborative approach so that the needs of both departments are met, providing a sound basis for future cooperation between the departments. More sophisticated systems now incorporate the ‘how’ as well (see IDS 2003).

Planning the support, development and resources necessary for employees to achieve their objectives is imperative. Without this support it is unlikely that even the most determined employees will achieve the performance required.

Concerns have been expressed over restricting the objectives to those which specify output targets, and there is now evidence of increasing use of input targets, such as developing a critical competency which is valued by the organisation and relevant to the achievement of objectives. Williams (2002) argues that as individuals cannot always control their results it is important to have behavioural targets as well as output targets. It is also recommended that there is a personal development plan which would again underpin the achievement of objectives.

2.3. Delivering and monitoring performance

While the employee is working to achieve the performance agreed, the manager retains a key enabling role. Organising the resources and off-job training is clearly essential. So too is being accessible. There may well be unforeseen barriers to the agreed performance which the manager needs to deal with, and sometimes the situation will demand that the expected performance needs to be revised. The employee may want to sound out possible courses of action with the manager before proceeding, or may require further information. Sharing ‘inside’ information that will affect the employee’s performance is often a key need, although it is also something that managers find difficult, especially

with sensitive information. Managers can identify information sources and other people who may be helpful.

Ongoing coaching during the task is especially important as managers guide employees through discussion and by constructive feedback. They can refer to practical job experiences to develop the critical skills and competencies that the employee needs, and can provide job-related opportunities for practice. Managers can identify potential role models to employees, help to explain how high achievers perform so well, and oil the organisational wheels.

Employees carry out ongoing reviews to plan their work and priorities and also to advise the manager well in advance if the agreed performance will not be delivered by the agreed dates. Joint employee/manager review ensures that information is shared. For example, a manager needs to be kept up to date on employee progress, while the employee needs to be kept up to date on organisational changes that have an impact on the agreed objectives. Both need to share perceptions of how the other is doing in their role, and what they could do that would be more helpful.

These reviews are normally informal, although a few notes may be taken of progress made and actions agreed. They need not be part of any formal system and therefore can take place when the job or the individuals involved demand, and not according to a pre-set schedule. The review is to facilitate future employee performance, providing an opportunity for the manager to confirm that the employee is ‘on the right track’, redirecting him or her if necessary. They thus provide a forum for employee reward in terms of recognition of progress. A ‘well done’ or an objective signed off as completed can enhance the motivation to perform well in the future. During this period evidence collection is also important. In the Scottish Prison Service (IDS 2003) line managers maintain a performance monitoring log of their team members’ positive and negative behaviours in order to provide regular feedback and to embed the practice of ongoing assessment. Employees are expected to build up a portfolio of evidence of their performance over the period to increase the objectivity of reviews and to provide an audit trail to back up any assessment ratings. It is also during this part of the cycle that employees in many organisations can collect 360-degree feedback to be used developmentally and as part of an evidence base.

2.4. Formal performance review/assessment

Regular formal reviews are needed to concentrate on developmental issues and to motivate the employee. Also, an annual review and assessment is needed, of the extent to which objectives have been met – and this may well affect pay received. In many organisations, for example Microsoft and AstraZeneca, employees are now invited to prepare an initial draft of achievement against objectives (IDS 2003). Some organisations continue to have overall assessment ratings which have to conform to a forced distribution, requiring each team/department to have, say, 10 per cent of employees on the top point, 20 per cent on the next point, and so on, so that each individual is assessed relative to others rather than being given an absolute rating. These systems are not popular and Roberts (2004) reports how staff walked out in a part of the Civil Service over relative assessment; AstraZeneca does not encourage its managers to give an overall rating to staff at all as its research suggested that this was demotivating (IDS 2003). Research by the Institute for Employment Studies (IRS 2001) found that review was only seen as fair if the targets set were seen as reasonable, managers were seen to be objective and judgements were consistent across the organisation.

Some organisations encourage employees to give upward feedback to their managers at this point in the cycle. For further details of this stage in the process see the Focus on skills at the end of Part 3.

2.5. Reward

Many systems still include a link with pay, but Fletcher and Williams (1992) point to some difficulties experienced. Some public and private organisations found that the merit element of pay was too small to motivate staff, and sometimes seen as insulting. Although performance management organisations were more likely than others to have merit or performance-related pay (Bevan and Thompson 1992), some organisations have regretted its inclusion. Armstrong and Baron (1998a) report that staff almost universally disliked the link with pay, and a manager in one of their case study companies reported that ‘the whole process is an absolute nightmare’ (p. 172). Clark (2005) provides a good discussion of the problems with the pay link and we include a detailed discussion of performance related pay in Chapter 28.

There are other forms of reward than monetary and the Institute for Employment Studies (IRS 2001) found that there was more satisfaction with the system where promotion and development, rather than money, were used as rewards for good performance.

3. INDIVIDUAL VERSUS TEAM PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT

There is one key aspect of employee performance management which we have yet to touch upon and that is how organisations can use performance management to support team performance as well as individual performance. This is a critical balancing act in most cases as, if managers and employees are not mindful in their objective setting, development, review and reward process, there can be conflicts built into performance management activity causing employees’ pursuit of individual objectives to damage the performance of the team they are in and vice versa. The complications that can arise and the way they are best dealt with will depend very much on the type of team(s) to which the employee belongs and the individual circumstances. Below we consider different types of team situations and the challenges these bring for performance management, and how both individual performance and team performance can best be enhanced at the same time.

It is generally agreed that team working has increased but this may take many forms. First, let us look at the situation where an employee has a base role in a departmental team, such as the ‘training team’, ‘contracts team’, ‘schools marketing team’ for example, reflecting where that person is placed in the organisation and who their line manager is. If this is the only team to which the employee belongs then it is highly likely that he or she will agree individual performance management objectives with the team leader which relate to the employee’s role in the achievement of the team’s objectives. One of those individual objectives may of course focus on collegiality or support to other members of the functional team.

However many employees will at the same time be members of other teams, perhaps ongoing cross-functional teams or time-limited cross-functional problem-solving teams. The objectives for this cross-functional team may be owned elsewhere in the organisation. One danger in such a situation is that if the employee does not have at least one objective relating to his or her role in this second team then this aspect of his or her job may suffer as effort is prioritised on areas that purely relate to his or her home team. This will be especially so if any kind of reward is attached to achievement of objectives. So neglect of a part of the employee’s job relating to the second team is the first potential problem. The remedy to this is fairly straightforward, but easily overlooked. An objective relating to the contribution the employee makes to the second team needs to be included (an input objective), or alternatively an objective relating to the achievement of one or more objectives of the second team (an output objective). An example of the first may concern the team role the employee is required to play in that second team, perhaps focusing on strengthening it, if it is not well developed, or concern the skills that are needed in that team given its stage of development, or concern the extent to which the employee is collaborative in his or her work with the team. An example of the second may concern, say, the team delivering on a target date, to the standard agreed, or other output targets it has agreed.

The second potential problem is that the employee’s individual objectives may actually conflict with the objectives of the second team of which he or she is a part. This conflict may be political in nature, where the home team leader agrees an objective with an individual that he or she should influence the second team to, for example, plan in a certain amount of training, before the roll-out of a new IT system. However if roll-out is to commence on the target date agreed by the second team, fitting in this training may be extremely difficult, if not impossible. The employee in this situation may not be able to win, either he or she fails to achieve his or her individual objective or the second team of which he or she is a part fails to achieve one of its objectives.

Van Vijfeijken et al. (2006) provide another example of potential conflict in relation to the operation of management teams, where the employee (this time a departmental head) has individual objectives relating to the achievement of the department’s objectives, but is also part of the organisation’s management team which has its own set of objectives. The researchers identified potential conflicts between the individual objectives of different department heads in the management team, and also between any individual head’s goals and the team goals. An example here might be that a department head of marketing has an objective relating to cost reductions in their department, whereas a management team goal may concern an extensive marketing campaign to launch a new product. There is a great deal written about how such management teams need to distance themselves from their department (see, for example, Garratt 1990) and operate in the interests of the organisation as a whole. This is clearly difficult if the department head has individual objectives relating to the department, which will drive monetary or other rewards. Such contradictions need to be openly aired at an early stage, but this is often not the case, due to lack of awareness, inertia or politicking.

We turn now to consider permanent self-managed teams or the like. Often in such teams all performance management objectives are team based, with the whole team needing to pull together to achieve these objectives effectively. In such teams there may in addition be individual input objectives such as skills development. These teams are more likely to fit the classical definition of a team. Moxon (1993) defines a team as having a common purpose; agreed norms and values which regulate behaviour; members with interdependent functions; and a recognition of team identity. Katzenbach and Smith (1993) and Katzenbach (1997) have also described the differences that they see between teams and work groups, and identify teams as comprising individuals with complementary skills, shared leadership roles, mutual accountability and a specific team purpose, amongst other attributes. In organisations this dedication only happens when individuals are fully committed to the team’s goals. This commitment derives from an involvement in defining how the goals will be met and having the power to make decisions within teams rather than being dependent on the agreement of external management. These are particularly characteristics of self-managing teams.

The problems most likely to occur with team objectives in this setting are peer pressure and social loafing (see, for example, Clark 2005). Peer pressure can be experienced by an individual, such as for example, the pressure not to take time off work when feeling ill, as this may damage achievement of objectives; or pressure to work faster, make fewer mistakes and so on. This pressure is likely to be much greater when rewards are attached to the achievement of team objectives. Individuals will vary in the competitiveness and in the value they place on monetary rewards and this may cause a pressure for all. Social loafing occurs in a situation where one or more team members rely on the others to put in extra effort to achieve objectives, to cover for their own lack of effort. It works when some members are known to be conscientious or competitive or to care deeply about the rewards available, and there are others who are likely to be less concerned and who know the conscientious team members will make sure by their own efforts that the objectives are achieved.

4. IMPLEMENTATION AND CRITIQUE OF PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT

Performance management needs to be line driven rather than HR driven, and therefore mechanisms need to be found to make this happen. The incorporation of line managers alongside HR managers in a working party to develop the system is clearly important as it not only takes account of the needs of the line in the system design, but also demonstrates that the system is line led. Training in the introduction and use of the system is also ideally line led, and Fletcher and Williams (1992) give us an excellent example of an organisation where line managers were trained as ‘performance management coaches’ who were involved in departmental training and support for the new system. However, some researchers have found that line managers are the weak link in the system (see, for example, Hendry et al. 1997). The Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) (see IRS 2001) notes that any system is only as good as the people who operationalise it. See Case 13.1 at www.pearsoned.co.uk/torrington which deals with the introduction of a performance management system.

Bevan and Thompson (1992) found incomplete take-up of performance management, with some aspects being adopted and not others. They noted that there was a general lack of integration of activities. This is rather unfortunate as one of the key advantages of performance management is the capacity for integration of activities concerned with the management of individual performance. This problem is still apparent. Hendry et al. (1997) reported the comments of Phil Wills from GrandMet, that there is still little understanding of what an integrated approach to performance management means. While alignment is critical, some organisations do not understand whether their HR processes are aligned or pulling in different directions. Williams (2002) suggests that there is still confusion over the nature of performance management.

Performance management seems to suffer from the same problems as traditional appraisal systems. Armstrong and Baron (1998a) report, for example, that over half the respondents to their survey feel that managers give their best ratings to people that they like (p. 202), and over half the managers surveyed felt that they had not received sufficient training in performance management processes (p. 203). They also report (1998b) that the use of ratings was consistently derided by staff and seen as subjective and inconsistent. Performance ratings can be seen as demotivating, and forced distributions are felt to be particularly unfair. Yet Houldsworth (2003) found 44 per cent of the Henley and Hay Group survey sample did this.

In terms of individual objective setting linked to organisational performance objectives, there are problems when strategy is unclear and when it evolves. Rose (2000) also reports a range of problems, particularly the fact that SMART targets can be problematic if they are not constantly reviewed and updated, although this is a time-consuming process. Pre-set objectives can be a constraining factor in such a rapidly changing business context, and they remind us of the trap of setting measurable targets, precisely because they are measurable and satisfy the system, rather than because they are most important to the organisation. He argues that a broader approach which assesses the employee’s accomplishments as a whole and the contribution to the organisation is more helpful than concentrating on pre-set objectives. Williams (2002) also notes that there is more to performance than task performance, such as volunteering and helping others. He refers to this as contextual performance; it is sometimes referred to as collegiate behaviour.

A further concern with SMART targets is that they inevitably have a short-term focus, yet what is most important to the organisation is developments which are complex and longer term, which are very difficult to pin down to short-term targets (see, for example, Hendry et al. 1997). In this context systems which also focus on the development of competencies will add greater value in the longer term. Armstrong and Baron (1998b) do note that a more rounded view of performance is gradually being adopted, which involves the ‘how’ as well as the ‘what’, and inputs such as the development of competencies. There is, however, a long way to go adequately to describe performance and define what is really required for organisational success.

For an in-depth example of performance management in the Scottish Prison Service see Case 13.2 at www.pearsoned.co.uk/torrington.

5. 360-DEGREE FEEDBACK

The term 360-degree feedback, a very specific term used to refer to multi-rater feedback, is increasingly being used within performance management systems and as a separate development activity.

5.1. The nature of 360-degree feedback

This approach to feedback refers to the use of the whole range of sources from which feedback can be collected about any individual. Thus feedback is collected from every angle on the way that the individual carries out his or her job: from immediate line manager; peers; subordinates; more senior managers; internal customers; external customers; and from individuals themselves. It is argued that this breadth provides better feedback than relying on the line manager only, who will only be able to observe the individual in a limited range of situations, and Atwater and his colleagues (2002) suggest that 360-degree feedback provides a better way to capture the complexities of performance. Hogetts et al. (1999) report that more than 70 per cent of United Parcels Service employees found that feedback from multiple sources was more useful in developing self-insight than feedback from a single source. Individuals, it is argued, will find feedback from peers and subordinates compelling and more valid (see, for example, Borman 1997 and Atwater et al. 2001), and Edwards and Ewen (1996, p. 4) maintain that:

No organizational action has more power for motivating employee behaviour change than feedback from credible work associates.

Such all-round feedback enables the individual to understand how he or she may be seen differently (or similarly) by different organisational groups, and how this may contrast with the individuals own views of his or her strengths and weaknesses. This provides powerful information for the development of self-awareness. While 360-degree feedback may be collected using informal methods, as shown in the Window on practice box on Humberside Tec, the term itself is a registered trade mark, and refers to a very specific method of feedback collection and analysis which was devised in the United States (see Edwards and Ewen 1996, p. 19), and they suggest that ‘simplistic, informal approaches to multi-source assessment are likely to multiply rather than reduce error’. However, informal approaches to 360-degree feedback are sometimes used quite successfully as an alternative to a survey questionnaire and statistical analysis.

The formal process is a survey approach which involves the use of a carefully constructed questionnaire that is used with all the contributors of feedback. This questionnaire may be bought off the peg, providing a well-tested tool, or may be developed internally, providing a tool which is more precisely matched to the needs of the organisation. Whichever form is used, the essence is that it is based on behavioural competencies (for a more detailed explanation of these see Chapter 17), and their associated behaviours. Contributors will be asked to score, on a given scale, the extent to which the individual displays these behaviours. Using a well-designed questionnaire, distributed to a sufficient number of contributors and employing appropriate sophisticated analysis, for example specifically designed computer packages which are set up to detect and moderate collusion and bias on behalf of the contributors, should provide reliable and valid data for the individual. The feedback is usually presented to the individual in the form of graphs or bar charts showing comparative scores from different feedback groups, such as peers, subordinates, customers, where the average will be provided for each group, and single scores from line manager and self. In most cases the individual will have been able to choose the composition of the contributors in each group, for example which seven subordinates, out of a team of 10, will be asked to complete the feedback questionnaire. But beyond this the feedback will be anonymous as only averages for each group of contributors will be reported back, except for the line manager’s score. The feedback will need to be interpreted by an internal or external facilitator, and done via a face-to-face meeting. It is generally recommended that the individual will need some training in the nature of the system and how to receive feedback, and the contributors will need some training on how to provide feedback. The principle behind the idea of feedback is that individuals can then use this information to change their behaviours and to improve performance, by setting and meeting development goals and an action plan.

Reported benefits include a stronger ownership of development goals, a climate of constructive feedback, improved communication over time and an organisation which is more capable of change as continuous feedback and improvement have become part of the way people work (Cook and Macauley 1997). Useful texts on designing and implementing a system include Edwards and Ewen (1996) from the US perspective

and Ward (1995) from the UK perspective. A brief ‘how to do it guide’ is Goodge and Watts (2000).

5.2. Difficulties and dilemmas

As with all processes and systems there needs to be clarity about the purpose. Most authors distinguish between developmental uses, which they identify as fairly safe and a good way of introducing such a system, and other uses, such as to determine pay awards. There seems to be an almost universal view that using these data for pay purposes is not advisable, and in the literature from the United States there is clearly a concern about the legal ramifications of doing this. Ward (1998) provides a useful framework for considering the different applications of this type of feedback, and reviews in some detail other applications such as using 360-degree feedback as part of a training course to focus attention for each individual on what he or she needs to get out of the course. Other applications he suggests include using 360-degree feedback as an approach to team building, as a method of performance appraisal/management, for organisation development purposes and to evaluate training and development. Edwards and Ewen (1996) suggest that it can be used for nearly all HR systems, using selection, training and development, recognition and the allocation of job assignments as examples.

Most approaches to 360-degree feedback require rater confidentiality as well as clarity of purpose, and this can be difficult to maintain with a small team, so raters may feel uncomfortable about being open and honest. In their research Pillutla and Ronson (2006) demonstrate how peer evaluations may be biased and warn against recruitment, reward and promotion decisions being made on this basis. The dangers of collusion and bias need to be eliminated, and it is suggested that the appropriate software systems can achieve this, but they are of course expensive, as are well-validated off-the-peg systems.

Follow-up is critical and if the experience of 360-degree feedback is not built on via the construction of development goals and the support and resources to fulfil these, the process may be viewed negatively and may be demotivating. There is an assumption that the provision of such feedback will motivate the individuals receiving it to develop and improve their performance, but Morgan and Cannan (2005) found very mixed results in their Civil Service research. One-third of their respondents were not motivated to act on the feedback and in this case felt that the 360-degree process was an isolated act with lack of follow-up, depending heavily on the proactivity of the individuals involved, with little support.

London et al. (1997) report concerns about the way systems are implemented, and that nearly one-third of respondents they surveyed experienced negative effects. Atwater and his colleagues (2002) found some negative reactions such as reduced effort, dissatisfaction with peers who provided the feedback and a lower commitment to colleagues. Fletcher and Baldry (2001) note that there are contradictions in the results from 360- degree feedback so far, and they suggest that further research is needed on how feedback affects self-esteem, motivation, satisfaction and commitment. The DTI (2001) suggested that sufficient resources need to be devoted to planning a system and that it should be piloted before general use. Clearly, 360-degree feedback needs to be handled carefully and sensitively and in the context of an appropriate organisational climate so that it is not experienced as a threat. The DTI (2001) suggested that there needs to be a climate of openness and trust for 360-degree feedback to work. Atwater et al. (2002) suggest that to counteract any negative effects it is important to prepare people for making their own ratings and on how they can provide honest and constructive feedback to others, ensure confidentiality and anonymity of raters, make sure the feedback is used developmentally and owned by the person being rated (for example that person may be the only one to receive the report), provide post-feedback coaching and encouragement and encourage people to follow up the feedback they have received.

Source: Torrington Derek, Hall Laura, Taylor Stephen (2008), Human Resource Management, Ft Pr; 7th edition.

Stunning quest there. What occurred after? Good luck!

Very interesting information!Perfect just what I was searching for!

Very fantastic information can be found on web site.