Another critical aspect of understanding behavior is perception. Perception is the cogni- tive process people use to make sense out of the environment by selecting, organizing, and interpreting information from the environment. Attitudes affect perceptions, and vice versa. For example, a person might have developed the attitude that managers are insensitive and arrogant, based on a pattern of perceiving arrogant and insensitive behavior from managers over a period of time. If the person moves to a new job, this attitude will continue to affect the way this person perceives superiors in the new environment, even though managers in the new workplace might take great pains to understand and respond to employees’ needs.

Because of individual differences in attitudes, personality, values, interests, and so forth, people often “see” the same thing in different ways. A class that is boring to one student might be fascinating to another. One student might perceive an assignment to be challenging and stimulating, whereas another might find it a silly waste of time. Referring to the topic of diversity discussed in Chapter 9, many African Americans perceive that blacks are regularly discriminated against, whereas many white employees perceive that blacks are given special opportunities in the workplace.18 Similarly, in a survey of financial profession executives, 40 percent of women perceive that women face a “glass ceiling” that keeps them from reaching top management levels, while only 10 percent of men share that perception.19

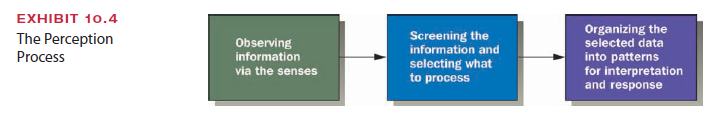

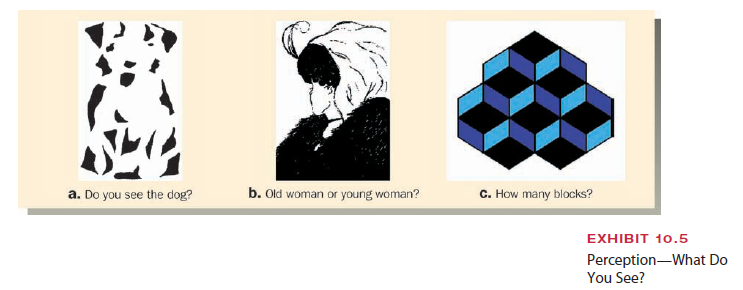

We can think of perception as a step-by-step process, as shown in Exhibit 10.4. First, we observe information (sensory data) from the environment through our senses: taste, smell, hearing, sight, and touch. Next, our mind screens the data and selects only the items we will process further. Third, we organize the selected data into meaningful patterns for interpretation and response. Most differences in perception among people at work are re- lated to how they select and organize sensory data. You can experience differences in per- ceptual organization by looking at the visuals in Exhibit 10.5. What do you see in part a of Exhibit 10.5? Most people see this as a dog, but others see only a series of unrelated ink- blots. Some people will see the figure in part b as a beautiful young woman, whereas others will see an old one. Now look at part c. How many blocks do you see—six or seven? Some people have to turn the figure upside down before they can see seven blocks. These visuals illustrate how complex perception is. Perception has a lot to do with how we view work- place interactions. Someone with a large ego will expect special treatment and would tend to see equal treatment as more-or-less unfair.

1. PERCEPTUAL SELECTIVITY

We all are aware of our environment, but not everything in it is equally important to our perception of it. We tune in to some data (e.g., a familiar voice off in the distance) and tune out other data (e.g., paper shuffling next to us). People are bombarded by so much sensory data that it is impossible to process it all. The brain’s solution is to run the data through a perceptual filter that retains some parts and eliminates others. Perceptual selectivity is the process by which individuals screen and select the various objects and stimuli that vie for their attention. Certain stimuli catch their attention, and others do not.

People typically focus on stimuli that satisfy their needs and that are consistent with their attitudes, values, and personality. For example, employees who need positive feedback to feel good about themselves might pick up on positive statements made by a supervisor but tune out most negative comments. A supervisor could use this understanding to tailor feedback in a positive way to help the employee improve work performance. The influence of needs on perception has been studied in laboratory experiments and found to have a strong impact on what people perceive.20

Characteristics of the stimuli themselves also affect perceptual selectivity. People tend to notice stimuli that stand out against other stimuli or that are more intense than sur- rounding stimuli. Examples are a loud noise in a quiet room or a bright red dress at a party where most women are wearing basic black. People also tend to notice things that are fa- miliar to them, such as a familiar voice in a crowd, as well as things that are new or differ- ent from their previous experiences. In addition, primacy and recency are important to per- ceptual selectivity. People pay relatively greater attention to sensory data that occur toward the beginning of an event or toward the end. Primacy supports the old truism that first impressions really do count, whether it be on a job interview, meeting a date’s parents, or participating in a new social group. Recency reflects the reality that the last impression might be a lasting impression. For example, Malaysian Airlines discovered its value in building customer loyalty. A woman traveling with a nine-month-old might find the flight itself an exhausting blur, but one such traveler enthusiastically told people for years how Malaysian Airlines flight attendants helped her with baggage collection and ground transportation.21

As these examples show, perceptual selectivity is a complex filtering process. Managers can use an understanding of perceptual selectivity to obtain clues about why one person sees things differently from others, and they can apply the principles to their own commu- nications and actions, especially when they want to attract or focus attention.

2. PERCEPTUAL DISTORTIONS

After people select the sensory data to be perceived, they begin grouping the data into recognizable patterns. Perceptual organization is the process by which people organize or categorize stimuli according to their own frame of reference. Of particular concern in the work environment are perceptual distortions, errors in perceptual judgment that arise from inaccuracies in any part of the perceptual process.

Some types of errors are so common that managers should become familiar with them. These include stereotyping, the halo effect, projection, and perceptual defense. Managers who recognize these perceptual distortions can better adjust their perceptions to more closely match objective reality.

Stereotyping is the tendency to assign an individual to a group or broad category (e.g., female, black, elderly; or male, white, disabled) and then to attribute widely held general- izations about the group to the individual. Thus, someone meets a new colleague, sees he is in a wheelchair, assigns him to the category “physically disabled,” and attributes to this colleague generalizations she believes about people with disabilities, which may include a belief that he is less able than other co-workers. However, the person’s inability to walk should not be seen as indicative of lesser abilities in other areas. Indeed, the assumption of limitations may not only offend him, but it also prevents the person making the stereotypi- cal judgment from benefiting from the many ways in which this person can contribute. Stereotyping prevents people from truly knowing those they classify in this way. In addi- tion, negative stereotypes prevent talented people from advancing in an organization and fully contributing their talents to the organization’s success.

The halo effect occurs when the perceiver develops an overall impression of a person or situation based on one characteristic, either favorable or unfavorable. In other words, a halo blinds the perceiver to other characteristics that should be used in generating a more com- plete assessment. The halo effect can play a significant role in performance appraisal, as we discussed in Chapter 9. For example, a person with an outstanding attendance record may be assessed as responsible, industrious, and highly productive; another person with less- than-average attendance may be assessed as a poor performer. Either assessment may be true, but it is the manager’s job to be sure the assessment is based on complete information about all job-related characteristics and not just his preferences for good attendance.

Projection is the tendency of perceivers to see their own personal traits in other people; that is, they project their own needs, feelings, values, and attitudes into their judgment of others. A manager who is achievement oriented might assume that subordinates are as well. This assumption might cause the manager to restructure jobs to be less routine and more challenging, without regard for employees’ actual satisfaction. The best guards against errors based on projection are self-awareness and empathy.

Perceptual defense is the tendency of perceivers to protect themselves against ideas, objects, or people that are threatening. People perceive things that are satisfying and pleas- ant but tend to disregard things that are disturbing and unpleasant. In essence, people develop blind spots in the perceptual process so that negative sensory data do not hurt them. For example, the director of a nonprofit educational organization in Tennessee hated dealing with conflict because he had grown up with parents who constantly argued and often put him in the middle of their arguments. The director consistently overlooked dis- cord among staff members until things would reach a boiling point. When the blowup occurred, the director would be shocked and dismayed because he had truly perceived that everything was going smoothly among the staff. Recognizing perceptual blind spots can help people develop a clearer picture of reality.

3. ATTRIBUTIONS

As people organize what they perceive, they often draw conclusions, such as about an object or a person. Among the judgments people make as part of the perceptual process are attributions. Attributions are judgments about what caused a person’s behavior— something about the person or something about the situation. An internal attribution says characteristics of the person led to the behavior. (“My boss yelled at me because he’s impatient and doesn’t listen.”) An external attribution says something about the situation caused the person’s behavior. (“My boss yelled at me because I missed the deadline, and the customer is upset.”) Attributions are important because they help people decide how to handle a situation. In the case of the boss yelling, a person who blames the yelling on the boss’s personality will view the boss as the problem and might cope by avoiding the boss. In contrast, someone who blames the yelling on the situation might try to help prevent such situations in the future.

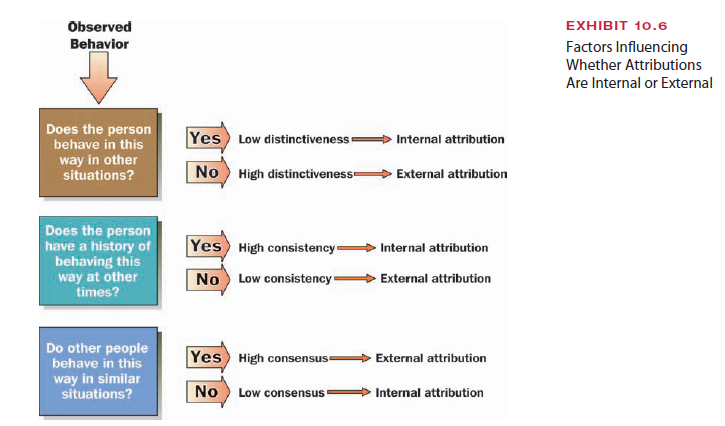

Social scientists have studied the attributions people make and identified three factors that influence whether an attribution will be external or internal.22 These three factors are illustrated in Exhibit 10.6.

- Distinctiveness. Whether the behavior is unusual for that person (in contrast to a person displaying the same kind of behavior in many situations). If the behavior is distinctive, the perceiver probably will make an external attribution.

- Consistency. Whether the person being observed has a history of behaving in the same way. People generally make internal attributions about consistent behavior.

- Consensus. Whether other people tend to respond to similar situations in the same way.

A person who has observed others handle similar situations in the same way will likely make an external attribution; that is, it will seem that the situation produces the type of behavior observed.

In addition to these general rules, people tend to have biases that they apply when making attributions. When evaluating others, we tend to underestimate the influence of external factors and overestimate the influence of internal factors. This tendency is called the fundamental attribution error. Consider the case of someone being promoted to CEO. Employees, outsiders, and the media generally focus on the characteristics of the person that allowed him or her to achieve the promotion. In reality, however, the selection of that person might have been heavily influenced by external factors, such as business con- ditions creating a need for someone with a strong financial or marketing background at that particular time.

Another bias that distorts attributions involves attributions we make about our own be- havior. People tend to overestimate the contribution of internal factors to their successes and overestimate the contribution of external factors to their failures. This tendency, called the self-serving bias, means people give themselves too much credit for what they do well and give external forces too much blame when they fail. Thus, if your manager says you don’t communicate well enough, and you think your manager doesn’t listen well enough, the truth may actually lie somewhere in between.

Source: Daft Richard L., Marcic Dorothy (2009), Understanding Management, South-Western College Pub; 8th edition.

I love it when people come together and share opinions, great blog, keep it up.